Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Buddha Revisited

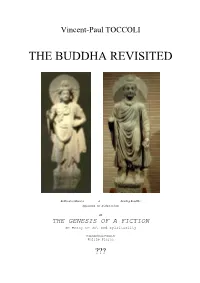

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

The Imperial Republic

HISTORYHISTORY — ROME The Imperial Republic Once a republic reluctant to fight wars except in selfdefense, Rome became an imperial colossus capable of annihilating an entire nation out of sheer spite. by Steve Bonta Romans, who had deployed extra infantry Rome by brute experience that imperial in the center of the formation in hopes of expansion has a high price. This is the third installment in a series of breaking through the Carthaginian lines, Rome had never been a peaceful state. articles on the rise and fall of the Roman found themselves outflanked by elite In the early centuries of the republic, how- Republic. North African cavalry units. Hannibal’s ever, many of Rome’s conflicts were pro- cavalry overwhelmed the Roman cavalry voked by jealous neighbors like the Vols- n all of human history, there have been on both flanks and then swept behind the cians and the Aequans. The early Italian few spectacles to rival the great battles Roman forces to attack from the rear. In peninsula was a tough neighborhood, with I of the ancient world, with their pag- short order, the Romans were completely rival Etruscan and Latin states, including eantry, color — and awful carnage. And hemmed in by the Carthaginians. Han- Rome, jostling for control, and the Gauls, few battles of that age could match the nibal’s numerically inferior forces then who occupied parts of northern Italy, fre- drama that unfolded under the hot Ital- slaughtered the Romans on the field al- quently making incursions southward. ian sun one August morning in 216 B.C. -

Philip V and Perseus: the Twilight of Antigonid Macedonia Philip V of Macedonia Was a Shrewd and Effective Leader. He Proved Ev

Philip V and Perseus: The Twilight of Antigonid Macedonia Philip V of Macedonia was a shrewd and effective leader. He proved even more adept than his predecessors at dealing with the Greek city-states, Illyrian invasions, and the other traditional concerns of his kingdom. Unfortunately for him, he was forced to deal with a completely new threat, for which he was unprepared—the rising power of Rome. Philip V and his son and successor Perseus failed in their conflicts with Rome, and ultimately allowed Macedonia to be conquered by the Romans. Since the wars they fought against Rome were recorded by Roman historians, they are known as the Macedonian Wars. Early Life and Reign of Philip V Philip V was the son of Demetrius II, who died in battle when Philip was nine years old. Since the army and nobility were hesitant to trust the kingdom to a child, they made Antigonas Doson regent, and then king. Antigonas honored Philip’s position, and when Antigonas died in 221 BC, Philip ascended smoothly to the throne at the age of seventeen. As the young king of Macedonia, Philip V was eager to prove his abilities. He defeated the Dardians in battle. When hostilities broke out between the two major leagues of Greek cities—the Achaean League and Aetolian League—he sided with Aratus and the Achaean League. Thanks to Philip’s intervention, the Achaeans achieved major victories against the Aetolians, and Aratus became one of Philip’s advisors. First Macedonian War (214–205 BC) In 219 BC, Demetrius of Pharos, the king of Illyria, fled to Philip’s court after being expelled by the Romans. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration. -

Politics and Policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C

Politics and policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C. Eric Brousseau, Department of History McGill University, Montreal June, 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. ©Eric Brousseau 2010 i Abstract Stephen Dyson’s The Creation of the Roman Frontier employs various anthropological models to explain the development of Rome’s republican frontiers. His treatment of the Ligurian frontier in the second century BC posits a Ligurian ‘policy’ crafted largely by the Senate and Roman ‘frontier tacticians’ (i.e. consuls). Dyson consciously avoids incorporating the pressures of domestic politics and the dynamics of aristocratic competition. But his insistence that these factors obscure policy continuities is incorrect. Politics determined policy. This thesis deals with the Ligurian frontier from 200 to 172 BC, years in which Roman involvement in the region was most intense. It shows that individual magistrates controlled policy to a much greater extent than Dyson and other scholars have allowed. The interplay between the competing forces of aristocratic competition and Senatorial consensus best explains the continuities and shifts in regional policy. Abstrait The Creation of the Roman Frontier, l’œuvre de Stephen Dyson, utilise plusieurs modèles anthropologiques pour illuminer le développement de la frontière républicaine. Son traitement de la frontière Ligurienne durant la deuxième siècle avant J.-C. postule une ‘politique’ envers les Liguriennes déterminer par le Sénat et les ‘tacticiens de la frontière romain’ (les consuls). Dyson fais exprès de ne pas tenir compte des forces de la politique domestique et la compétition aristocratique. Mais son insistance que ces forces cachent les continuités de la politique Ligurienne est incorrecte. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS the Ultimate Edition an Invaluable

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS The Ultimate Edition An invaluable resource for working programmers, as well as a fount of useful algorithmic tools for computer scientists, astronomers, and other calendar enthu- siasts, the Ultimate Edition updates and expands the previous edition to achieve more accurate results and present new calendar variants. The book now includes algorithmic descriptions of nearly forty calendars: the Gregorian, ISO, Icelandic, Egyptian, Armenian, Julian, Coptic, Ethiopic, Akan, Islamic (arithmetic and astro- nomical forms), Saudi Arabian, Persian (arithmetic and astronomical), Bahá’í (arithmetic and astronomical), French Revolutionary (arithmetic and astronomical), Babylonian, Hebrew (arithmetic and astronomical), Samaritan, Mayan (long count, haab, and tzolkin), Aztec (xihuitl and tonalpohualli), Balinese Pawukon, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Hindu (old arithmetic and medieval astronomical, both solar and lunisolar), and Tibetan Phug-lugs. It also includes information on major holidays and on different methods of keeping time. The necessary astronom- ical functions have been rewritten to produce more accurate results and to include calculations of moonrise and moonset. The authors frame the calendars of the world in a completely algorithmic form, allowing easy conversion among these calendars and the determination of secular and religious holidays. Lisp code for all the algorithms is available in machine- readable form. Edward M. Reingold is Professor of Computer Science at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Nachum Dershowitz is Professor of Computational Logic and Chair of Computer Science at Tel Aviv University. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information About the Authors Edward M. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Dancing Floor of Ares Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Central Greece

The Dancing Floor of Ares Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Central Greece Edited by Fabienne Marchand and Hans Beck ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Supplemental Volume 1 (2020) ISSN 0835-3638 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Monica D’Agostini, Andrea Gatzke, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Nadini Pandey, John Vanderspoel, Connor Whatley, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Contents 1 Hans Beck and Fabienne Marchand, Preface 2 Chandra Giroux, Mythologizing Conflict: Memory and the Minyae 21 Laetitia Phialon, The End of a World: Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Mycenaean Boeotia? 46 Hans Beck, From Regional Rivalry to Federalism: Revisiting the Battle of Koroneia (447 BCE) 63 Salvatore Tufano, The Liberation of Thebes (379 BC) as a Theban Revolution. Three Case Studies in Theban Prosopography 86 Alex McAuley, Kai polemou kai eirenes: Military Magistrates at War and at Peace in Hellenistic Boiotia 109 Roy van Wijk, The centrality of Boiotia to Athenian defensive strategy 138 Elena Franchi, Genealogies and Violence. Central Greece in the Making 168 Fabienne Marchand, The Making of a Fetter of Greece: Chalcis in the Hellenistic Period 189 Marcel Piérart, La guerre ou la paix? Deux notes sur les relations entre les Confédérations achaienne et béotienne (224-180 a.C.) Preface The present collection of papers stems from two one-day workshops, the first at McGill University on November 9, 2017, followed by another at the Université de Fribourg on May 24, 2018. Both meetings were part of a wider international collaboration between two projects, the Parochial Polis directed by Hans Beck in Montreal and now at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, and Fabienne Marchand’s Swiss National Science Foundation Old and New Powers: Boiotian International Relations from Philip II to Augustus. -

Descent from Lucius Cornelius Scipio

My Descendant Chart Lucius Cornelius Scipio b. ca 300 BC dp. Rome, Italy Publius Cornelius Scipio d. 211 BC, upper Baetis river, Hispania & Pomponia Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus b. 236 BC d. 3 Dec 183 BC, Liternum, Campania, Italy & Aemilia Paula Tertia b. ca 230 BC, Rome, Italy d. 163/164 BC Cornelia Scipionis Africana Major b. ca 201 BC & Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum m. ca 184 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio Pontifex Maximus b. 183 BC, Pergamon, Asia Minor d. 132 BC, Pergamon, Asia Minor Cornelia Scipionis Drusus II b. 153 BC d. 89 BC & Marcus Livius Drusa d. 108 BC Livia Drusa b. ca 120 BC d. ca 92 BC & Marcus Porcius Cato d. 118 BC Marcus Porcius Cato Catonis Minor Uticensis b. 95 BC, Rome, Italy d. Apr 46 BC, Utica, Italy & Atilia Uticensis m. ca 73 BC Porcia Catonis b. 72 BC d. 42 BC & Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus b. 102 BC, Rome, Italy d. 48 BC, Corcyra (Corfu), Greece m. btw 58 and 53 BC Gaius Calpurnius Bibulus b. 55 BC d. 35 & Domitia b. 50 BC Domitia Calvina b. 35 BC, Rome, Italy & Marcus Junius Silanus b. ca 35 BC, Rome, Italy d. 35 Junia Calvina Equitus b. ca 005 BC, Rome, Italy & Gaius Sallustius Crispus Passienus Equitius b. ca 015 BC, Visellium, Italy d. ca 47, Rome, Italy Gaius Salustius b. ca 015 & Ummidia Quadratilla Quadratus b. ca 028 Gaius Ummidius Quadratus Sallustius b. ca 45 & Sertoria Sallustius b. ca 68, Rome, Italy Gaius Ummidius Quadratus Annianus Verus Fulvius b. ca 110 & Annia Cornificia Faustina b. -

Hannibal Barca

Carthage Dispute over control of Sicily and trade routes in the western Carthage Mediterranean had been Result was the three brought Rome into founded as Punic Wars conflict with the Phoenician powerful North 264-146 BC colony 500 African city-state of years earlier Carthage The First Punic War Primarily a naval war Tactics: maneuver ship to ram and sink enemy Carthage: very good, experienced naval power Rome: small navy, little experience Defeated repeatedly by Carthaginian navy ROME WINS THE FIRST ONE Rome would not surrender Finally turned tables on Carthage by changing rules of naval warfare Equipped ships with huge hooks and stationed soldiers on ships Would hook enemy ship, pull nearby, board it with soldiers Converted naval warfare into mini-land battles, something Rome was very good at The Second Punic War "Hannibal ad portas" (“Hannibal is at the Gates!”) Carthagian general Hannibal surprises Romans, leads army from Spain, through southern France and the Alps Invades Italy from the north with elephant army Defeats Roman armies sent to stop him several times but hesitates to attack Rome itself Settles on war of attrition in hope of destroying Roman economic base ROME WINS THE SECOND ONE Unable to defeat Hannibal in Italy, a Roman army sailed across the Mediterranean, landed in North Africa, and headed for Carthage Led by patrician general Scipio Aemilius Africanus Hannibal forced to leave Italy to protect Carthage Defeated at the Battle of Zama, fought outside the walls of Carthage Hannibal Hannibal-the-Conqueror "I swear that so soon as age will permit . I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome." ~~Childhood Hannibal Quote Born about 247 - Died 183BC Hannibal Barca (247-183 BC) *Carthaginian general *Brilliant strategist *Developed tactics of outflanking and surrounding the enemy with the combined forces of infantry and cavalry As a boy of 9, begged his father, Hamilcar Barca, to take him on the campaign in Spain Hamilcar, made him solemnly swear eternal hatred of Rome.