Morton James DDJ 201106 MA.Pdf (1.313Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Processes of Byzantinisation and Serbian Archaeology Byzantine Heritage and Serbian Art I Byzantine Heritage and Serbian Art I–Iii

I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART AND SERBIAN BYZANTINE HERITAGE PROCESSES OF BYZANTINISATION AND SERBIAN ARCHAEOLOGY BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I–III Editors-in-Chief LJUBOMIR MAKSIMOVIć JELENA TRIVAN Edited by DANICA POPOVić DraGAN VOJVODić Editorial Board VESNA BIKIć LIDIJA MERENIK DANICA POPOVić ZoraN raKIć MIODraG MARKOVić VlADIMIR SIMić IGOR BOROZAN DraGAN VOJVODić Editorial Secretaries MARka TOMić ĐURić MILOš ŽIVKOVIć Reviewed by VALENTINO PACE ElIZABETA DIMITROVA MARKO POPOVić MIROSLAV TIMOTIJEVIć VUJADIN IVANIšEVić The Serbian National Committee of Byzantine Studies P.E. Službeni glasnik Institute for Byzantine Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts PROCESSES OF BYZANTINISATION AND SERBIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Editor VESNA BIKIć BELGRADE, 2016 PUBLished ON THE OCCasiON OF THE 23RD InternatiOnaL COngress OF Byzantine STUdies This book has been published with the support of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia CONTENTS PREFACE 11 I. BYZANTINISATION IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT THE DYNAMICS OF BYZANTINE–SERBIAN POLITICAL RELATIONS 17 Srđan Pirivatrić THE ‘MEDIEVAL SERBIAN OECUMENE’ – FICTION OR REALITY? 37 Mihailo St. Popović BYZANTINE INFLUENCE ON ADMINISTRATION IN THE TIME OF THE NEMANJIĆ DYNASTY 45 Stanoje Bojanin Bojana Krsmanović FROM THE ROMAN CASTEL TO THE SERBIAN MEDIEVAL CITY 53 Marko Popović THE BYZANTINE MODEL OF A SERBIAN MONASTERY: CONSTRUCTION AND ORGANISATIONAL CONCEPT 67 Gordana -

Was the Hauteville King of Sicily?*

Annick Peters-Custot »Byzantine« versus »Imperial« Kingdom: How »Byzantine« was the Hauteville King of Sicily?* The extent to which the Byzantine political model infl uenced the kingdom of the Hauteville dynasty in Southern Italy and in Sicily is still the subject of debate 1 . Some examples of the Byzantine infl uence on the so-called »Norman« monar- chy of Sicily are so obvious that this infl uence is considered dominant even if the concept of Byzantine inheritance is still an intensely discussed topic, in particular in art history 2 . Nevertheless, the iconographic examples include the famous mosaics showing the Hauteville king as a basileus, found in the Palermitan church of Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio (the so- called »Martorana church«, built by Georg of Antioch around the middle of the 12th century, fi g. 1) 3 , as well as in the Monreale cathedral, which was commissioned by King Wil- liam II (1166-1189) at the end of the same century 4 . In both cases, the king is wearing the renowned imperial garments, known as the loros and kamelaukion, as he is being crowned by Christ (in the Martorana church) and by the Theotokos – the Mother of God – in Monreale. In addition to these two famous examples, the Byzantine infl uence on the Hauteville kings can be found in areas beyond the iconographic fi eld. For instance, we see it in the Hauteville kings’ reliance on Greek notaries to write public deeds, such as the sigillion, according to Byzantine formal models 5 . Another example is the Greek signature of Roger II, which, in presenting the king as a protector of the Christians, evokes imperial pretensions 6 . -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

Poverty, Charity and the Papacy in The

TRICLINIUM PAUPERUM: POVERTY, CHARITY AND THE PAPACY IN THE TIME OF GREGORY THE GREAT AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTEENTH DAY OF MARCH, 2013 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ___________________________ Miles Doleac APPROVED: ________________________ Dennis P. Kehoe, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ F. Thomas Luongo, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ Thomas D. Frazel, Ph.D AN ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of Gregory I (r. 590-604 CE) in developing permanent ecclesiastical institutions under the authority of the Bishop of Rome to feed and serve the poor and the socio-political world in which he did so. Gregory’s work was part culmination of pre-existing practice, part innovation. I contend that Gregory transformed fading, ancient institutions and ideas—the Imperial annona, the monastic soup kitchen-hospice or xenodochium, Christianity’s “collection for the saints,” Christian caritas more generally and Greco-Roman euergetism—into something distinctly ecclesiastical, indeed “papal.” Although Gregory has long been closely associated with charity, few have attempted to unpack in any systematic way what Gregorian charity might have looked like in practical application and what impact it had on the Roman Church and the Roman people. I believe that we can see the contours of Gregory’s initiatives at work and, at least, the faint framework of an organized system of ecclesiastical charity that would emerge in clearer relief in the eighth and ninth centuries under Hadrian I (r. 772-795) and Leo III (r. -

Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; Proquest Pg

Reviving the Pagan Greek novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; ProQuest pg. 179 Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Joan B. Burton N THE CHRISTIAN WORLD of Constantinople, in the twelfth century A.D., there was a revival of the ancient Greek novel, I replete with pagan gods and pagan themes. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the crucial role of Christian themes such as the eucharist and the resurrection in the shaping and recreation of the ancient pagan Greek world in the Byzan tine Greek novels. Traditionally scholars have focused on similarities to the ancient Greek novels in basic plot elements, narrative tech niques, and the like. This has often resulted in a general dismissal of the twelfth-century Greek novels as imitative and unoriginal.1 Yet a revision of this judgment has begun to take place.2 Scholars have noted that there are themes and imagery in these novels that would sound contemporary to many of their Byzantine readers, for example, ceremonial throne scenes and 1 Thus B. E. Perry, The Ancient Romances: A Literary-Historical Account of Their Origins (Berkeley 1967) 103: "the slavish imitations of Achilles Tatius and Heliodorus which were written in the twelfth century by such miserable pedants as Eustathius Macrembolites, Theodorus Prodromus, and Nicetas Eugenianus, trying to write romance in what they thought was the ancient manner. Of these no account need be taken." 2See R. Beaton's important book, The Medieval Greek Romance 2 (London 1996) 52-88, 210-214; M. -

Byzantine Conquests in the East in the 10 Century

th Byzantine conquests in the East in the 10 century Campaigns of Nikephoros II Phocas and John Tzimiskes as were seen in the Byzantine sources Master thesis Filip Schneider s1006649 15. 6. 2018 Eternal Rome Supervisor: Prof. dr. Maaike van Berkel Master's programme in History Radboud Univerity Front page: Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas entering Constantinople in 963, an illustration from the Madrid Skylitzes. The illuminated manuscript of the work of John Skylitzes was created in the 12th century Sicily. Today it is located in the National Library of Spain in Madrid. Table of contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1 - Byzantine-Arab relations until 963 7 Byzantine-Arab relations in the pre-Islamic era 7 The advance of Islam 8 The Abbasid Caliphate 9 Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty 10 The development of Byzantine Empire under Macedonian dynasty 11 The land aristocracy 12 The Muslim world in the 9th and 10th century 14 The Hamdamids 15 The Fatimid Caliphate 16 Chapter 2 - Historiography 17 Leo the Deacon 18 Historiography in the Macedonian period 18 Leo the Deacon - biography 19 The History 21 John Skylitzes 24 11th century Byzantium 24 Historiography after Basil II 25 John Skylitzes - biography 26 Synopsis of Histories 27 Chapter 3 - Nikephoros II Phocas 29 Domestikos Nikephoros Phocas and the conquest of Crete 29 Conquest of Aleppo 31 Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas and conquest of Cilicia 33 Conquest of Cyprus 34 Bulgarian question 36 Campaign in Syria 37 Conquest of Antioch 39 Conclusion 40 Chapter 4 - John Tzimiskes 42 Bulgarian problem 42 Campaign in the East 43 A Crusade in the Holy Land? 45 The reasons behind Tzimiskes' eastern campaign 47 Conclusion 49 Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 Introduction In the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors coming from the Macedonian dynasty. -

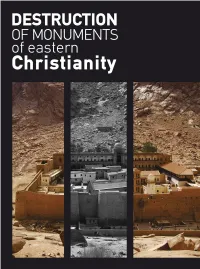

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected]

Georgia State University College of Law Reading Room Faculty Publications By Year Faculty Publications 1-1-2010 A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] John Khalil Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/faculty_pub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Ryan Rowberry & John Khalil, A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law, 3 Berk. J. Middle E. & Islamic L. 81 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications By Year by an authorized administrator of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry John Khalil* INTRODUCTION With the U.S.-led "War on Terror" and the occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, American legal scholars have understandably focused increased attention on the various schools and applications of Islamic law in Middle Eastern countries. 1 This focus on Shari'a law, however, has tended to elide the complexity of traditional legal pluralism in many Islamic nations. Numerous Christian communities across the Middle East (e.g., Syrian, Armenian, Coptic, Nestorian, Maronite), for example, adhere to personal status laws that are not based on Islamic legal principles. Christian minority groups form the largest non-Muslim . Ryan Rowberry and Jolin Khalil graduated from Harvard Law School in 2008. Ryan is currently a natural resources associate at Hogan Lovells US LLP in Washington D.C., and John Khalil is a litigation associate at Lowey, Dannenberg, Cowey & Hart P.C. -

ROGER II of SICILY a Ruler Between East and West

. ROGER II OF SICILY A ruler between east and west . HUBERT HOUBEN Translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org Originally published in German as Roger II. von Sizilien by Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 and C Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 First published in English by Cambridge University Press 2002 as Roger II of Sicily English translation C Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 10/11.5 pt. System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Houben, Hubert. [Roger II. von Sizilien. English] Roger II of Sicily: a ruler between east and west / Hubert Houben; translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn. p. cm. Translation of: Roger II. von Sizilien. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65208 1 (hardback) isbn 0 521 65573 0 (paperback) 1. Roger II, King of Sicily, d. -

Ukrainian Orthodox Calendar

АВОСЛАВ ПР НИ Й THODO Й R X И O К К N C А Ь A A I L Л С N E Е I Н Н N Ї A D Д А R A Р А K 2021 R К Р U У Personal Information - Особиста Iнформацiя Name - Iм’я Address - Адреса Phone - Телефон Parish - Парафiя Published by THE UKRAINIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH OF THE USA PO Box 495 South Bound Brook, NJ 08880 USA 1 From 1950 our Church has published the Ukrainian Orthodox Calendar. It has become not only a source of spiritual nourishment, but also the official directory UOC of the USA of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the USA. Metropolitan In order to better serve the faithful of the Orthodox Eastern Eparch Church our Calendar features: His Eminence Antony • directories of parishes and clergy • necrology of the clergy of UOC of the USA Consistory President • highlights of the past year Western Eparch • information about business services who His Eminence Archbishop Daniel contribute to the mission of our Church • Calendar Minea in English and Ukrainian languages Office of Public Relations Rev. Ivan Synevskyy The editorial board of the Ukrainian Orthodox Calendar 2021 prays that the readers of our almanac Calendar-Minea Preparation will find in it a true witness to the mission of our V. Rev. Pavlo Bodnarchuk Church in (modern) society. We look forward to receiving spiritual, historical and cultural articles for publication in future calendars. The Ukrainian Orthodox Calendar 2021 is an official publication of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Submissions should be sent to the USA and is distributed only by the Consistory. -

15Th-17Th Century) Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary (15Th-17Th Century) Edited by Giovanna Siedina

45 BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Giovanna Siedina Giovanna Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) Civilization in the Slavic World of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Essays on the Spread (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FUP FIRENZE PRESUNIVERSITYS BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI ISSN 2612-7687 (PRINT) - ISSN 2612-7679 (ONLINE) – 45 – BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Editor-in-Chief Laura Salmon, University of Genoa, Italy Associate editor Maria Bidovec, University of Naples L’Orientale, Italy Scientific Board Rosanna Benacchio, University of Padua, Italy Maria Cristina Bragone, University of Pavia, Italy Claudia Olivieri, University of Catania, Italy Francesca Romoli, University of Pisa, Italy Laura Rossi, University of Milan, Italy Marco Sabbatini, University of Pisa, Italy International Scientific Board Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, University of Milan, Italy Maria Giovanna Di Salvo, University of Milan, Italy Alexander Etkind, European University Institute, Italy Lazar Fleishman, Stanford University, United States Marcello Garzaniti, University of Florence, Italy Harvey Goldblatt, Yale University, United States Mark Lipoveckij, University of Colorado-Boulder , United States Jordan Ljuckanov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria Roland Marti, Saarland University, Germany Michael Moser, University of Vienna, Austria Ivo Pospíšil, Masaryk University, Czech Republic Editorial Board Giuseppe Dell’Agata, University of Pisa, Italy Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRESS 2020 Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th- 17th Century) / edited by Giovanna Siedina. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2020. -

Imperial Spheres and the Adriatic

Review Copy Only - Not for Redistribution Sauro Gelichi - Universita Ca' Foscari Venice - 10/26/2017 Imperial Spheres and the Adriatic Although often mentioned in textbooks about the Carolingian and Byzantine empires, the Treaty of Aachen has not received much close attention. This volume attempts not just to fill the gap, but to view the episode through both micro- and macro-lenses. Introductory chapters review the state of relations between Byzan- tium and the Frankish realm in the eighth and early ninth centuries, crises facing Byzantine emperors much closer to home, and the relevance of the Bulgarian problem to affairs on the Adriatic. Dalmatia’s coastal towns and the populations of the interior receive extensive attention, including the region’s ecclesiastical history and cultural affiliations. So do the local politics of Dalmatia, Venice and the Carolingian marches, and their interaction with the Byzantino-Frankish con- frontation. The dynamics of the Franks’ relations with the Avars are analysed and, here too, the three-way play among the two empires and ‘in-between’ parties is a theme. Archaeological indications of the Franks’ presence are collated with what the literary sources reveal about local elites’ aspirations. The economic dimen- sion to the Byzantino-Frankish competition for Venice is fully explored, a special feature of the volume being archaeological evidence for a resurgence of trade between the Upper Adriatic and the Eastern Mediterranean from the second half of the eighth century onwards. Mladen Ančić is Professor of History at the Universities of Zadar and Zagreb. He has published on the Hungarian-Croatian kingdom and Bosnia in the fourteenth century, the medieval city of Jajce, and historiography and nationalism.