Louis D. Brandeis and the Origins of Free Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defence of the Court's Integrity

In Defence of the Court’s Integrity 17 In Defence of the Court’s Integrity: The Role of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in the Defeat of the Court-Packing Plan of 1937 Ryan Coates Honours, Durham University ‘No greater mistake can be made than to think that our institutions are fixed or may not be changed for the worse. We are a young nation and nothing can be taken for granted. If our institutions are maintained in their integrity, and if change shall mean improvement, it will be because the intelligent and the worthy constantly generate the motive power which, distributed over a thousand lines of communication, develops that appreciation of the standards of decency and justice which we have delighted to call the common sense of the American people.’ Hughes in 1909 ‘Our institutions were not designed to bring about uniformity of opinion; if they had been, we might well abandon hope.’ Hughes in 1925 ‘While what I am about to say would ordinarily be held in confidence, I feel that I am justified in revealing it in defence of the Court’s integrity.’ Hughes in the 1940s In early 1927, ten years before his intervention against the court-packing plan, Charles Evans Hughes, former Governor of New York, former Republican presidential candidate, former Secretary of State, and most significantly, former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, delivered a series 18 history in the making vol. 3 no. 2 of lectures at his alma mater, Columbia University, on the subject of the Supreme Court.1 These lectures were published the following year as The Supreme Court: Its Foundation, Methods and Achievements (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928). -

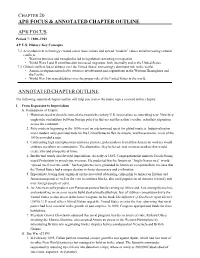

Chapter 20 Ap® Focus & Annotated Chapter Outline Ap® Focus

CHAPTER 20 AP® FOCUS & ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE AP® FOCUS Period 7: 1890–1945 AP U.S. History Key Concepts 7.2 A revolution in technology created a new mass culture and spread “modern” values amid increasing cultural conflicts. • Wartime tensions and xenophobia led to legislation restricting immigration. • World Wars I and II contributed to increased migration, both internally and to the United States. 7.3 Global conflicts led to debates over the United States’ increasingly dominant role in the world. • American expansionism led to overseas involvement and acquisitions in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific. • World War I increased debates over the proper role of the United States in the world. ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE The following annotated chapter outline will help you review the major topics covered in this chapter. I. From Expansion to Imperialism A. Foundations of Empire 1. Historians used to describe turn-of-the-twentieth-century U.S. imperialism as something new. Now they emphasize continuities between foreign policy in this era and the nation’s earlier, relentless expansion across the continent. 2. Policymakers beginning in the 1890s went on a determined quest for global markets. Industrialization and a modern navy provided tools for the United States to flex its muscle, and the economic crisis of the 1890s provided a spur. 3. Confronting high unemployment and mass protests, policymakers feared that American workers would embrace socialism or communism. The alternative, they believed, was overseas markets that would create jobs and prosperity at home. 4. Intellectual trends also favored imperialism. As early as 1885, Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong urged Protestants to proselytize overseas. -

Espionage Act of 1917

Communication Law Review An Analysis of Congressional Arguments Limiting Free Speech Laura Long, University of Oklahoma The Alien and Sedition Acts, Espionage and Sedition Acts, and USA PATRIOT Act are all war-time acts passed by Congress which are viewed as blatant civil rights violations. This study identifies recurring arguments presented during congressional debates of these acts. Analysis of the arguments suggests that Terror Management Theory may explain why civil rights were given up in the name of security. Further, the citizen and non-citizen distinction in addition to political ramifications are discussed. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 are considered by many as gross violations of civil liberties and constitutional rights. John Miller, in his book, Crisis in Freedom, described the Alien and Sedition Acts as a failure from every point of view. Miller explained the Federalists’ “disregard of the basic freedoms of Americans [completed] their ruin and cost them the confidence and respect of the people.”1 John Adams described the acts as “an ineffectual attempt to extinguish the fire of defamation, but it operated like oil upon the flames.”2 Other scholars have claimed that the acts were not simply unwise policy, but they were unconstitutional measures.3 In an article titled “Order vs. Liberty,” Larry Gragg argued that they were blatantly against the First Amendment protections outlined only seven years earlier.4 Despite popular opinion that the acts were unconstitutional and violated basic civil liberties, arguments used to pass the acts have resurfaced throughout United States history. Those arguments seek to instill fear in American citizens that foreigners will ultimately be the demise to the United States unless quick and decisive action is taken. -

Book Review: the Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection

BOOK REVIEW THE BRANDEIS/FRANKFURTER CONNECTION; by Bruce Allen Murphy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. 473 pp. $18.95. Reviewed by Judith Resnikt Shouldl be more serviceableto the State, ifI took an employment, where function would be wholly bounded in my person, and take up all my time, than I am by instructing everyone, as I do, andin furnishing the Republic with a great number of citizens who are capable to serve her? XENoHON'S M EMORABIL bk. 1, ch. 6, para. 15 (ed 1903), as quoted in a letter by Louis . Brandeis to Felix Frankfurter(Jan. 28, 1928).' I THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN JUSTICE BRANDEIS AND PROFESSOR FRANKFURTER From the same bits of information-letters, fragmentary notes, in- dividuals' recollections, newspaper and historical accounts-several different stories can emerge, as the storyteller brings to the materials his or her own personal concerns and hypotheses. From reading some of the correspondence between Justices Brandeis and Frankfurter,2 biog- raphies of each,3 and assorted articles about them and the times in which they lived,4 I envision the following exchanges between Brandeis and Frankfurter: The year was 1914. A young law professor, Felix Frankfurter, went to t Associate Professor of Law, University of Southern California Law Center. B.A. 1972, Bryn Mawr College; J.D. 1975, New York University School of Law. I wish to thank Dennis E. Curtis, William J. Genego, and Daoud Awad for their helpful comments. 1. 5 LETTERS OF Louis D. BRANDEIS 319 (M. Urofsky & D. Levy eds. 1978) [hereinafter cited as LETTERS]. 2. E.g., 1-5 LETTERs, supra note 1. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

The US Air Force After Vietnam: Postwar Challenges and Potential for Responses / by Donald J

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mrozek, Donald J. The US Air Force after Vietnam: postwar challenges and potential for responses / by Donald J. Mrozek. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes Index. 1. United States-Military policy. 2. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975-Public opinion. 3. Public opinion- United States. 4. United States. Air Force. l. Title. II. Title: United States Air Force afterVietnam. UA23.M76 1988 88-7476 355' .0335'73-dc 19 CIP ISBN 1-58566-024-8 First Printing December 1988 Second Printing July 2001 DISCLAIMER This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflectthe official policy or position of the Department of Defenseor the United States government. This publication has been reveiwed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release . For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents US Government Printing Office Washington DC 20402 ii 7~ THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK CONTENTS Chapter Page DISCLAIMER ... .... .... ............ .... .... .... .... .... ... .... .... .... ii FOREWORD . .... .... ... .... .... ... .... .... .... ........ .... .... .... ... vii ABOUT THE AUTHOR. .... .... .... .... ... .... .... .... ..... .... .. ix PREFACE.... ... .... .... ... .... .... .... ........ .... .... .... ... .... .... xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .. .. ...... .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. -

World War I - on the Homefront

World War I - On the Homefront Teacher’s Guide Written By: Melissa McMeen Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: WORLD WAR I—ON THE HOMEFRONT TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 4 Instructional Notes .................................................... 5 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 6 Student Objectives .................................................... 6 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 6 Internet Resources .................................................... 7 Answer Key .................................................... 8 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 12 Blackline Masters Index .................................................... 20 Pre-Test .................................................... 21 Video Quiz .................................................... 22 Post-Test .................................................... 23 Discussion Questions .................................................... 27 Vocabulary Terms .................................................... 28 Woman’s Portrait .................................................... 29 -

Louis Brandeis: a Man for This Season

LOUIS BRANDEIS: A MAN FOR THIS SEASON JONATHAN SALLET* In the early years of the 20th century, Louis Brandeis was America’s most influential advocate for antitrust enforcement, but his contributions to antitrust have been much debated ever since. Given the current, prominent discussion of the future of antitrust in these economic times, this essay proposes a five-part framework to describe Brandeis’s approach, which relies heavily on institutional roles and responsibilities: (1) legislators creating antitrust laws should consider broad economic and social issues, including democratic values; (2) antitrust laws should translate those broad motivations into administrable legal standards within the scope of professional obligations familiar to antitrust enforcers and the courts; (3) legal professionals vindicate the legislature’s larger social and economic goals by relying on learnings from economics and the social sciences and applying the chosen legal standard to the facts in a determined and detailed manner, while avoiding day-to-day political considerations; (4) sectoral regulation should be used where Justified by specific industry circumstances, such as the existence of local utility monopolies or in circumstances in which normal competitive forces cannot get the Job done; and (5) competition policy, both in antitrust and sectoral regulation, is to be informed by a spirit of experimentation. * Senior Fellow, The Benton Foundation. I am very appreciative to the following for their comments on drafts of this essay: Jonathan Baker, Gerald Berk, Teddy Downey, Kenneth Ewing, Adrianne Furniss, Renata Hesse, Caroline Holland, Herbert Hovenkamp, Lina Khan, Fiona Scott Morton, Carl Shapiro, George Slover, Kevin Taglang, and Tom Wheeler as well as to Andrew Manley and Ryland Sherman for their research assistance. -

Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E

HOW WWI CHANGED AMERICA Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E. CODDINGTON, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CONTEXT Although the United States is a nation with defined rights protected by a constitution, sometimes those rights are challenged by the circumstances at hand. This is especially true during wartime and times of crisis. As Americans remained divided in their support for World War I, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and U.S. Congress pushed pro- war propaganda and enacted laws meant to deter anti-war protesting. When war protests did arise, those who challenged U.S. involvement in the war faced heavy consequences, including jail time for their actions. Many questioned the pro-war campaign and its possible infringement on Americans’ First Amendment freedoms, including the right to protest and freedom of speech. Using World War I as a backdrop and the First Amendment as the test, students will examine the Sedition Act of 1918 and come to realize that Congress passed laws that violated the Constitution and that the Supreme Court upheld those laws. Additionally, students will be challenged to consider the role President Wilson had in promoting an anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and how that rhetoric emboldened Congress to pass laws that violated the civil rights of all Americans. The lesson will wrap up challenging students to consider the responsibilities of citizens when they believe the president and Congress promote legislation that infringes on First Amendment rights. PRIMARY SOURCES Eugene Debs -

Clippings Scrapbook II

Clippings Scrapbook II Items without a page number were inserted between pages. Genealogy of the Wehle Family of Prague “Brandeis—The Old Story of the Prophet” Boston American 6/4/1931 p.1‐3 Remarks by C.N. Jones October 1908 p.4‐5 “Former Louisville Man Leading Fight for the People’s Rights” Louisville Herald 6/1/1908 p.6‐7 “Stories of Success” Boston American 10/4/1908 p.8 “Louis Brandeis, Kentuckian, is Famed Fighter for People’s Rights” Louisville Herald 2/8/1910 p.9‐11 “Brandeis Sherlock Holmes’ Rival; Deductive Powers Amaze Enemies” Boston Traveler 6/10/1910 p.12‐13 “Personalities” Hampton Magazine June 1910 p.14‐19 “Brandeis, Teacher of Business Economy” New York Times 12/4/1910 p.20 12/5/1910 letter to New York Times from William F. Peters p.21 “An Attorney for the People” Outlook 12/24/1910 p.22‐24 “A Great American” Philadelphia North American 2/11/1911 p. 25 “Brandeis Refused Pay for Subway Lease Work” Boston Journal 2/25/1911 p.26 “’Citizen’ Brandeis” Boston Post 2/25/1911 p.27 “Louis Brandeis” The Electrical Worker February 1911 p.28 ? The World Today February 1911 p.29‐31 “Players in the Great Game” System February 1911 P.32‐37 “Who is This Man Brandeis?” Human Life February 1911 7/28/1880 letter from (Annie Fields ?) 8(?)/2/1880 letter from Charles Smith Bradley 1/26/1882 letter from J.O. Shaw Jr. (Union Boat Club) p.38‐50 “Brandeis” American Magazine February 1911 12/14/1883 letter from illegible 5/8/1884 letter from George H. -

Wyoming Liberty Group and the Goldwater Institute Scharf-Norton Center for Constitutional Litigation in Support of Appellant on Supplemental Question

No. 08-205 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- CITIZENS UNITED, Appellant, v. FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, Appellee. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The District Of Columbia --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE WYOMING LIBERTY GROUP AND THE GOLDWATER INSTITUTE SCHARF-NORTON CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LITIGATION IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT ON SUPPLEMENTAL QUESTION --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BENJAMIN BARR Counsel of Record GOVERNMENT WATCH, P.C. 619 Pickford Place N.E. Washington, DC 20002 (240) 863-8280 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Historic Truths: The Powerful Few Forever Seek to Silence Dissent ................................ 5 II. This Court Cannot Design a Workable Standard to Weed Out “Impure” Speech ..... 11 III. A Return to First Principles: Favoring Unbridled Dissent ....................................... -

The Jeffersonian Jurist? a R Econsideration of Justice Louis Brandeis and the Libertarian Legal Tradition in the United States I

MENDENHALL_APPRVD.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/17 3:27 PM THE JEFFERSONIAN JURIST? A RECONSIDERATION OF JUSTICE LOUIS BRANDEIS AND THE LIBERTARIAN LEGAL TRADITION IN THE UNITED STATES * BY ALLEN MENDENHALL I. BRANDEIS AND LIBERTARIANISM ..................................................... 285 II. IMPLICATIONS AND EFFECTS OF CLASSIFYING BRANDEIS AS A LIBERTARIAN .............................................................................. 293 III. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 306 The prevailing consensus seems to be that Justice Louis D. Brandeis was not a libertarian even though he has long been designated a “civil libertarian.”1 A more hardline position maintains that Brandeis was not just non-libertarian, but an outright opponent of “laissez-faire jurisprudence.”2 Jeffrey Rosen’s new biography, Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet, challenges these common understandings by portraying Brandeis as “the most important American critic of what he called ‘the curse of bigness’ in government and business since Thomas Jefferson,”3 who was a “liberty-loving” man preaching “vigilance against * Allen Mendenhall is Associate Dean at Faulkner University Thomas Goode Jones School of Law and Executive Director of the Blackstone & Burke Center for Law & Liberty. Visit his website at AllenMendenhall.com. He thanks Ilya Shapiro and Josh Blackman for advice and Alexandra SoloRio for research assistance. Any mistakes are his alone. 1 E.g., KEN L. KERSCH, CONSTRUCTING CIVIL LIBERTIES: DISCONTINUITIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 112 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2004); LOUIS MENAND, THE METAPHYSICAL CLUB: A STORY OF IDEAS IN AMERICA 66 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2001); David M. Rabban, The Emergence of Modern First Amendment Doctrine, 50 U. CHI. L. REV. 1205, 1212 (1983); Howard Gillman, Regime Politics, Jurisprudential Regimes, and Unenumerated Rights, 9 U.