A Concise Review of the Iranian Calendar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farvardin Yasht Contents Fravashi Is Generally Translated As the “Guardian Spirit/Angel.” It Occurs for a Total of 539 Times in the Extant Avesta

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 136 – Who were all these Stalwarts of our Religion? - Corroboration from Aafrin-e-Rapithwan with Farvardin Yasht for a few of them! Hello all Tele Class friends: Afargaan, Farokshi, Satums, Baaj – Prayers for our dear departed ones I grew up in Tarapur in a Panthaki’s family and on each anniversary occasions of dear departed ones of family or of our Tarapur Humdins, usually referred to as the day of Baaj, the following four prayers were performed in the name of the departed: Afargaan, Farokshi, 3 Satums and a Baaj. During the Muktaad days, these prayers were performed for all the departed ones whose Behraa (vessels) were placed on the Muktaad tables. In current scenario in India, especially during the Muktaad days, very few Atash Behrams/Agiaries perform all these prayers for all dear departed ones. In North America, except for the major cities, only Afargaan and may be Satums are performed for the dear departed ones. In these prayers, Farokshi is nothing but the Farvardin Yasht with Satum No Kardo in front of it. In this WZSE, we will cover some very interesting facts about some contents of the Farvardin Yasht. Farvardin Yasht Contents Fravashi is generally translated as the “Guardian Spirit/Angel.” It occurs for a total of 539 times in the extant Avesta. Of these, 353 times (65.5%) are in the Farvardin Yasht. This Yasht (Veneration) is devoted to Fravashi. It is the longest Yasht in the extant Avesta with 157 verses. The Meher Yasht, in honor of Mithra, the deity of light and Pasture land, is the second with 145 verses, and the Aban Yasht, in honor of Aredvi Sura Anahita, the River Deity is the third with 132 verses. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Chap 3 Zoroastrian-Factsheet.Pdf

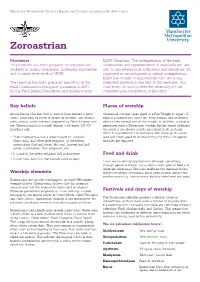

Manchester Metropolitan University Equality and Diversity information factsheet stage 1 Zoroastrian Disclaimer MMU Chaplains. The interpretation of the faith, This resource has been prepared to help staff and observances and representation of standards etc. are students in raising awareness, increasing knowledge part of this professional judgement and should not be and to assist their work at MMU. construed as an authorised or official interpretation. MMU has sought to acknowledge the use of any The resource has been prepared according to the published material in the text of this resource. Any Faith Communities Navigator’ published in 2007 inadvertent omissions deemed necessary will be by the Faith Regen Foundation and guidance from corrected upon notification of this error. Key beliefs Places of worship Ahura Mazda (the one God) is said to have created a good Communal worship takes place in a Fire Temple or Agiary. It world, consisting of seven elements of creation: sky, waters, houses a burning fire called the Adur Aduran (fire of flames), earth, plants, cattle, humans (regarded as God’s helpers) and which is the central part of the temple. In addition, a ritual is fire. Zoroastrianism is a small religion with about 140,000 performed each a Zoroastrian washes his/her hands although members and: the ritual is not always strictly performed in all its detail. When it is performed, the individual will stand on the same • Their theology has had a great impact on Judaism, spot and must speak to on one during the ritual. No special Christianity and other later religions, in the beliefs facilities are required. -

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Ordibehesht of the Year 1398

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Ordibehesht of the Year 13981 Increase in All Households Inflation Rate The general index (base year: 1395=100) stood at 173.5 in the month of Ordibehesht2 of the year 1398 indicating a 1.5 percent rise compared with the previous month. In this month, the percentage change in the general index was 52.1 percent in contrast to the corresponding month of the previous year, that is to say that the national households spent, on average, 52.1 percent higher than the month of Ordibehesht in the year 1397 for purchasing “the same goods and services”, which increased by 0.7 percentage point over the previous month (51.4 percent). The twelve-month inflation rate ending the month of Ordibehesht of the year 1398 reached 34.2 percent which rose by 3.6 percentage points over the same information in the previous month (30.6 percent). The CPI for the major groups of "food, beverages and tobacco" decreased by 0.7 percent and for "non-food items and services" increased by 2.7 percent, respectively in contrast to the previous month. The percentage changes in prices in the current month for these two groups were 82.6 and 39.9 percent compared with the month of Ordibehesht in the year 1397, respectively. Increase in All Urban Households Inflation Rate The general price index for all urban households in the month of Ordibehesht of the year 1398 stood at 172.0 showing a 1.6 percent increase from the last month. Percentage change in the general index was 50.7 percent in comparison with the same month in the last year, which rose by 0.7 percentage point over the previous month (50.0 percent). -

0.GEMATRIA DATABASE.Pages

GEMATRIA - DATABASE ! Bavarian Illuminati Est. May 1st, 1776} 5/01/1776 ! Scottish Rite Est. May 31, 1801 } 5/31/1801 Knights Templar ARRESTED on Oct. 13, 1307 } 10/12/1307 ! Knights Templar FOUNDED in Jerusalem, Israel: 1119 ! Skull & Bones 322 FOUNDED in 1832 at Yale University) (Russell Trust Association - Parent Organization) 322 references 322 BC ! Vatican City Est. February 11, 1929 (109 acres) ! One legend is that the numbers in the society's emblem ("322") represent "founded in '32, 2nd corps", referring to a first Corps in an unknown German university.[22][23] ! Convocation founded in 1539 (3rd Papal Bull) Jesuits founded in 1541 Copernicus of 1543 (Ball Earth) The Council of Trent founded in 1545 ! (Christopher Columbus) America discovered in 1492 (2 Papal Bulls) 1912 = Titanic sank 1913 = Federal Reserve Established 1914 = First World War 1917 = Bolshevik Communist Invasion ! Jewish Bolshevism, also known as Judeo-Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist canard [citation needed] which alleges that the Jews were at the origin of the Russian Revolution and held the primary power among Bolsheviks. Similarly, the Jewish Communism theory implies that Jews have been dominating the Communist movements in the world. It is similar to the ZOG conspiracy theory, which asserts that Jews control world politics. The expressions have been used as a catchword for the assertion that Communism is a Jewish conspiracy. ! Hexagram = Star of David ! Pythagoras the Samian or Pythagoras of Samos (570-495 BC) was a mathematician, Ionian Greek -

To:$M.R$Ahmad$Shahid$ Special$Rapporteur$On$The

To:$M.r$Ahmad$Shahid$ Special$Rapporteur$on$the$human$rights$situation$in$Iran$ $ Dear%Sir,% % such%as%equal%rights%to%education%for%everyone,%preventing%the%dismissal%and%forced%retirements%of% dissident%university%professors,%right%of%research%without%limitations%in%universities%and%to%sum%up% expansion%of%academic%liberties.%Student%activists%have%also%been%pursuing%basic%rights%of%the%people% such%as%freedom%of%speech,%press,%and%rallies,%free%formation%and%function%of%parties,%syndicates,%civil% associations%and%also%regard%of%democratic%principles%in%the%political%structure%for%many%years.% % But%unfortunately%the%regime%has%rarely%been%friendly%towards%students.%They%have%always%tried%to%force% from%education,%banishments%to%universities%in%remote%cities,%arrests,%prosecutions%and%heavy%sentences% of%lashing,%prison%and%even%incarceration%in%banishment,%all%for%peaceful%and%lawful%pursuit%of%the% previously%mentioned%demands.%Demands%which%according%to%the%human%rights%charter%are%considered% the%most%basic%rights%of%every%human%being%and%Islamic%Republic%of%Iran%as%a%subscriber%is%bound%to% uphold.% % The%government%also%attempts%to%shut%down%any%student%associations%which%are%active%in%peaceful%and% lawful%criticism,%and%their%members%are%subjected%to%all%sorts%of%pressures%and%restrictions%to%stop%them.% Islamic%Associations%for%example%which%have%over%60%years%of%history%almost%twice%as%of%the%Islamic% republic%regimeE%and%in%recent%years%have%been%the%only%official%criticizing%student%associations%in% universities,%despite%their%massive%number%of%student%members,%have%been%shut%down%by%the% -

Summary of the Assets and Liabilities of the Banking System

Table 1 SUMMARY OF THE ASSETS AND LIABILITIES OF THE BANKING SYSTEM (1) (billion rials) Year-end balance Percentage change Ordibehesht Ordibehesht Ordibehesht Ordibehesht Ordibehesht Esfand Ordibehesht Esfand Ordibehesht 1385 to 1386 to 1385 to 1386 to 1384 1384 1385 1385 1386 Ordibehesht Ordibehesht Esfand Esfand 1384 1385 1384 1385 Assets Foreign assets 626,886.9 770,170.4 799,821.4 928,552.5 957,655.3 27.6 19.7 3.8 3.1 Claims on public sector 238,439.2 235,607.7 236,051.1 256,219.8 269,849.3 -1.0 14.3 0.2 5.3 Government 147,588.6 135,794.5 137,542.1 160,269.3 174,463.5 -6.8 26.8 1.3 8.9 Public corporations and agencies 90,850.6 99,813.2 98,509.0 95,950.5 95,385.8 8.4 -3.2 -1.3 -0.6 Claims on non-public sector 636,344.1 865,315.4 882,475.8 1,226,201.0 1,268,190.2 38.7 43.7 2.0 3.4 Others 295,811.1 488,302.9 433,775.5 671,235.9 635,783.4 46.6 46.6 -11.2 -5.3 Sub-total 1,797,481.3 2,359,396.4 2,352,123.8 3,082,209.2 3,131,478.2 30.9 33.1 -0.3 1.6 Below the line items 412,609.8 445,191.6 439,828.3 599,812.1 613,946.3 6.6 39.6 -1.2 2.4 Total assets = total liabilities 2,210,091.1 2,804,588.0 2,791,952.1 3,682,021.3 3,745,424.5 26.3 34.2 -0.5 1.7 Liabilities Liquidity 682,418.4 921,019.4 921,027.0 1,284,199.4 1,314,977.7 35.0 42.8 0 2.4 Money 230,253.8 317,919.4 287,499.3 414,544.9 390,298.3 24.9 35.8 -9.6 -5.8 Quasi-money 452,164.6 603,100.0 633,527.7 869,654.5 924,679.4 40.1 46.0 5.0 6.3 Loans and deposits of the public sector 143,020.4 167,667.4 217,330.9 220,621.4 235,271.1 52.0 8.3 29.6 6.6 Government 133,632.2 156,378.9 202,322.4 208,532.4 -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Study on the Relationship Between Temperature

Bulletin of Environment, Pharmacology and Life Sciences Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci., Vol 3 [12] November 2014: 42-45 ©2014 Academy for Environment and Life Sciences, India Online ISSN 2277-1808 Journal’s URL:http://www.bepls.com CODEN: BEPLAD Global Impact Factor 0.533 Universal Impact Factor 0.9804 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A study on the relationship between temperature and height in Ardabil province, according to the meteorological data Bahman Bahari Bighdilu Department of Agriculture, Pars Abad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, pars Abad Moghan, Iran Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT the relationship between temperature and height was investigated Based on the review of one of the most important climatic parameters (temperature) in order to provide scientific solutions to meet the social needs and careful planning in the region in the field of agriculture. There was a significant relationship on the basis of Laps Rate phenomenon, so that the differences between heating and cooling processes of 70 degrees Celsius and the height difference of 1500 meters in the province show this important issue. Keywords: temperature, according, meteorological data Received 10.09.2014 Revised 09.10.2014 Accepted 02.11. 2014 INTRODUCTION Location, range and area This region with the area of 17,867 square kilometers is located at the north of Iran plateau between the coordinates of '45 and ‘37 to '42 and '39 North latitude and '55 and 48 to '3 and 47 east longitudes from the Greenwich meridian. Based on the assessment studies of Land resources in this area (Ardabil Province) a total of 7 major types and one type of mixed lands and 32 units of land have been identified. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Middle Eastern Festivals Islamic

Middle Eastern Festivals Islamic: Moulid el-Nabi, Milad, Milad an-Nabi, or Mawlid un-Nabi (The Prophet’s Birthday) Prophet Muhammad (also Mohammed, Muhammed, Mahomet, and other variants) is the founder of Islam and is regarded by Muslims as the last messenger and prophet of God. Muhammad was born in the year 570 AD and his birthday is celebrated each year on 12 Rabi el-Awal, following the Islamic calendar. Processions are held, homes or mosques are decorated, charity and food is distributed, stories about the life of Muhammad are narrated, and poems are recited by children. The main purpose of Moulid el-Nabi gatherings is to remember, observe, discuss and celebrate the advent of the birth and teachings of the holy Prophet Muhammad. Ramadan Ramadan is a celebration that takes place in the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, when the Quran (the central religious text of Islam) was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. The name of the feast is the name of the month. Muslims celebrate Ramadan for an entire month. It is a time for prayers (some people pray 5 times a day), friendship, and thinking about how to help others. Many people fast during the hours of daylight for the entire month. Before the sun rises, families gather to eat a big breakfast. This breakfast before dawn is called Suhoor (also called Sehri, Sahari and Sahur in other languages). Each family member then fasts until the sun sets in the evening. After the sun sets, they have a big supper. This evening meal for breaking the daily fast is called Iftar and is often done as a community, with Muslims gathering to break their fast together. -

Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars*

BASELLO E LAM AND BABYLONIA : THE EVIDENCE OF THE CALENDARS GIAN PIETRO BASELLO Napoli Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars * Pochi sanno estimare al giusto l’immenso benefizio, che ogni momento godiamo, dell’aria respirabile, e dell’acqua, non meno necessaria alla vita; così pure pochi si fanno un’idea adeguata delle agevolezze e dei vantaggi che all’odierno vivere procura il computo uniforme e la divisione regolare dei tempi. Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, 1892 1 Babylonians and Elamites in Venice very historical research starts from Dome 2 just above your head. Would you a certain point in the present in be surprised at the sight of two polished Eorder to reach a far-away past. But figures representing the residents of a journey has some intermediate stages. Mesopotamia among other ancient peo- In order to go eastward, which place is ples? better to start than Venice, the ancient In order to understand this symbolic Seafaring Republic? If you went to Ven- representation, we must go back to the ice, you would surely take a look at San end of the 1st century AD, perhaps in Marco. After entering the church, you Rome, when the evangelist described this would probably raise your eyes, struck by scene in the Acts of the Apostles and the golden light floating all around: you compiled a list of the attending peoples. 3 would see the Holy Spirit descending If you had an edition of Paulus Alexan- upon peoples through the preaching drinus’ Sã ! Ğ'ã'Ğ'·R ğ apostles. You would be looking at the (an “Introduction to Astrology” dated at 12th century mosaic of the Pentecost 378 AD) 4 within your reach, you should * I would like to thank Prof.