Botanic and Poetic Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 Days Persia Classic Tour Overview

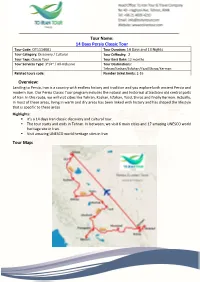

Tour Name: 14 Days Persia Classic Tour Tour Code: OT1114001 Tour Duration: 14 Days and 13 Nights Tour Category: Discovery / Cultural Tour Difficulty: 2 Tour Tags: Classic Tour Tour Best Date: 12 months Tour Services Type: 3*/4* / All-inclusive Tour Destinations: Tehran/Kashan/Esfahan/Yazd/Shiraz/Kerman Related tours code: Number ticket limits: 2-16 Overview: Landing to Persia, Iran is a country with endless history and tradition and you explore both ancient Persia and modern Iran. Our Persia Classic Tour program includes the natural and historical attractions old central parts of Iran. In this route, we will visit cities like Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, Shiraz and finally Kerman. Actually, in most of these areas, living in warm and dry areas has been linked with history and has shaped the lifestyle that is specific to these areas. Highlights: . It’s a 14 days Iran classic discovery and cultural tour. The tour starts and ends in Tehran. In between, we visit 6 main cities and 17 amazing UNESCO world heritage site in Iran. Visit amazing UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran Tour Map: Tour Itinerary: Landing to PERSIA Welcome to Iran. To be met by your tour guide at the airport (IKA airport), you will be transferred to your hotel. We will visit Golestan Palace* (one of Iran UNESCO World Heritage site) and grand old bazaar of Tehran (depends on arrival time). O/N Tehran Magic of Desert (Kashan) Leaving Tehran behind, on our way to Kashan, we visit Ouyi underground city. Then continue to Kashan to visit Tabatabayi historical house, Borujerdiha/Abbasian historical house, Fin Persian garden*, a relaxing and visually impressive Persian garden with water channels all passing through a central pavilion. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series MED2013-0656

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: MED2013-0656 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series MED2013-0656 Quest for Identity: Representation of Ottoman Images in the Turkish Mass Media Bahar Senem Çevik Assistant Professor Ankara University Center for the Study and Research of Political Psychology Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: MED2013-0656 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 31/10/2013 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: MED2013-0656 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research 3 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: MED2013-0656 This paper should be cited as follows: Çevik, B.S. -

Day 1: Flight from Your Home Country to Tehran Capital of IRAN

Day 1: Flight from your home country to Tehran capital of IRAN We prepare ourselves for a fabulous trip to Great Persia. Arrival to Tehran, after custom formality, meet and assist at airport and transfer to the Hotel. Day 2: Tehran After breakfast in hotel, we prepare to start for city sightseeing, visit Niyavaran Palace,Lunch in a local restaurant during the visit .In the afternoon visit Bazaar Tajrish and Imamzadeh Saleh mausoleu. The NiavaranComplex is a historical complex situated in Shemiran, Tehran (Greater Tehran), Iran. It consists of several buildings and monuments built in the Qajar and Pahlavi eras. The complex traces its origin to a garden in Niavaran region, which was used as a summer residence by Fath-Ali Shah of the Qajar Dynasty. A pavilion was built in the garden by the order of Naser ed Din Shah of the same dynasty, which was originally referred to as Niavaran House, and was later renamed Saheb Qaranie House. The pavilion of Ahmad Shah Qajarwas built in the late Qajar period.During the reign of the Pahlavi Dynasty, a modern built mansion named Niavaran House was built for the imperial family of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. All of the peripheral buildings of the Saheb Qaranie House, with the exception of the Ahmad Shahi Pavilion, were demolished, and the buildings and structures of the present-day complex were built to the north of the Saheb Qaranie House. In the Pahlavi period, the Ahmad Shahi Pavilion served as an exhibition area for the presents from world eaders to the Iranian monarchs. Im?mz?deh S?leh is one of many Im?mzadeh mosques in Iran. -

Persianism in Antiquity

Oriens et Occidens – Band 25 Franz Steiner Verlag Sonderdruck aus: Persianism in Antiquity Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2017 CONTENTS Acknowledgments . 7 Rolf Strootman & Miguel John Versluys From Culture to Concept: The Reception and Appropriation of Persia in Antiquity . 9 Part I: Persianization, Persomania, Perserie . 33 Albert de Jong Being Iranian in Antiquity (at Home and Abroad) . 35 Margaret C. Miller Quoting ‘Persia’ in Athens . 49 Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones ‘Open Sesame!’ Orientalist Fantasy and the Persian Court in Greek Art 430–330 BCE . 69 Omar Coloru Once were Persians: The Perception of Pre-Islamic Monuments in Iran from the 16th to the 19th Century . 87 Judith A. Lerner Ancient Persianisms in Nineteenth-Century Iran: The Revival of Persepolitan Imagery under the Qajars . 107 David Engels Is there a “Persian High Culture”? Critical Reflections on the Place of Ancient Iran in Oswald Spengler’s Philosophy of History . 121 Part II: The Hellenistic World . 145 Damien Agut-Labordère Persianism through Persianization: The Case of Ptolemaic Egypt . 147 Sonja Plischke Persianism under the early Seleukid Kings? The Royal Title ‘Great King’ . 163 Rolf Strootman Imperial Persianism: Seleukids, Arsakids and Fratarakā . 177 6 Contents Matthew Canepa Rival Images of Iranian Kingship and Persian Identity in Post-Achaemenid Western Asia . 201 Charlotte Lerouge-Cohen Persianism in the Kingdom of Pontic Kappadokia . The Genealogical Claims of the Mithridatids . 223 Bruno Jacobs Tradition oder Fiktion? Die „persischen“ Elemente in den Ausstattungs- programmen Antiochos’ I . von Kommagene . 235 Benedikt Eckhardt Memories of Persian Rule: Constructing History and Ideology in Hasmonean Judea . -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

European Journal of Turkish Studies, 19 | 2014 Re-Creating History and Recreating Publics: the Success and Failure of Recent

European Journal of Turkish Studies Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey 19 | 2014 Heritage Production in Turkey. Actors, Issues, and Scales - Part I Re-creating history and recreating publics: the success and failure of recent Ottoman costume dramas in Turkish media. Josh Carney Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/5050 DOI: 10.4000/ejts.5050 ISSN: 1773-0546 Publisher EJTS Electronic reference Josh Carney, « Re-creating history and recreating publics: the success and failure of recent Ottoman costume dramas in Turkish media. », European Journal of Turkish Studies [Online], 19 | 2014, Online since 22 December 2014, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ ejts/5050 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ejts.5050 This text was automatically generated on 10 December 2020. © Some rights reserved / Creative Commons license Re-creating history and recreating publics: the success and failure of recent... 1 Re-creating history and recreating publics: the success and failure of recent Ottoman costume dramas in Turkish media. Josh Carney AUTHOR'S NOTE I am grateful to the Wenner Gren Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, and Indiana University for providing the funds to support both this research and its writing, and to my advisor, Jon Simons, and the reviewers and editorial board of EJTS for their assistance in shepherding this project through various revisions. 1 On 25 November 2012, while speaking at the opening ceremony for an airport in the city of Kütahya, then Turkish Prime Minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan veered from his remarks on the progress Turkey had seen under the past decade of his Justice and Development Party’s (AK-Party) rule to lambast one of the country’s most popular TV shows, the sometimes sultry Ottoman costume drama Magnificent Century [Muhteşem Yüzyıl], which depicts the sixteenth century reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. -

MASTER's THESIS Tourism Attractions and Their Influence On

2009:057 MASTER'S THESIS Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Reza Abyareh Luleå University of Technology Master Thesis, Continuation Courses Marketing and e-commerce Department of Business Administration and Social Sciences Division of Industrial marketing and e-commerce 2009:057 - ISSN: 1653-0187 - ISRN: LTU-PB-EX--09/057--SE 1 Master Thesis Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Peter U.C.Dieke and Prof.Dr.Ali Sanayei By: Reza Abyareh Fall 2007 2 Master Thesis Tourism and Hotel Management Lulea University of Technology (Sweden) and University of Isfahan(Iran) Tourism Attractions and their Influence on Handicraft Employment in Isfahan Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Peter U.C.Dieke and Prof.Dr.Ali Sanayei By: Reza Abyareh A Master Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Master of Tourism and Hotel Management in Lulea University of Technology. Fall 2007 3 In The Name of God ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dedicated to My parents and my sister,the most important three persons in my life. 4 Contents ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Acknowledgements 1 Overview 7 Introduction 7 Key Words 8 Description of Research Problem 9 Importance and Value of Research 10 Record and History of Research Subject 11 Purposes of Research 12 Research Questions 12 Sample size 13 Research Method 13 Tools for Collecting Data 13 Data Collection and Analysis -

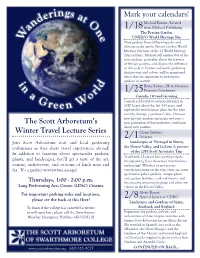

W Rings a Ne Reen W Or

erings at Mark your calendars! d O Michael Brown, Retired n 1/18 from Medical Publishing a n The Persian Garden W e UNESCO World Heritage Site Nine gardens from different epochs and climates make up the Persian Garden World Heritage Site (one of the 21 World Heritage Sites in Iran). Michael will explore five of the nine gardens, generalize about the features of Persian gardens, and discuss the influence of this style in Iranian and world gardening. Architecture and culture will be mentioned when they are important to viewing the i gardens in context. n d Becky Robert, PR & Volunteer rl 1/25Programs Coordinator a o Canada: 150 and Growing G Canada celebrated its sesquicentennial in r W 2017. Learn about the last 150 years, and ee n explore the revitalization plans for the next century through a gardener’s lens. Discover how historic gardens and parks welcome a The Scott Arboretum’s new generation of horticulturists, and learn about new gardens. Winter Travel Lecture Series Claire Sawyers, 2/1 Director Join Scott Arboretum staff and local gardening Landscapes of Portugal in Sintra, enthusiasts as they share travel experiences abroad! the Douro Valley, and Lisbon: A preview of the 2018 Scott Associates Trip In addition to learning about spectacular gardens, Travel with Claire on her scouting trip for plants, and landscapes, you’ll get a taste of the art, the upcoming Scott Associates international cuisine, architecture, and customs of lands near and garden trip! Whether or not you are far. It’s a perfect wintertime escape! considering going on the trip, come see some spectacular palace gardens, unique places and garden features, cork oak forests, and Thursdays, 1:00 - 2:00 p.m. -

Jnasci-2015-1195-1202

Journal of Novel Applied Sciences Available online at www.jnasci.org ©2015 JNAS Journal-2015-4-11/1195-1202 ISSN 2322-5149 ©2015 JNAS Relationships between Timurid Empire and Qara Qoyunlu & Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens Jamshid Norouzi1 and Wirya Azizi2* 1- Assistant Professor of History Department of Payame Noor University 2- M.A of Iran’s Islamic Era History of Payame Noor University Corresponding author: Wirya Azizi ABSTRACT: Following Abu Saeed Ilkhan’s death (from Mongol Empire), for half a century, Iranian lands were reigned by local rules. Finally, lately in the 8th century, Amir Timur thrived from Transoxiana in northeastern Iran, and gradually made obedient Iran and surrounding countries. However, in the Northwest of Iran, Turkmen tribes reigned but during the Timurid raids they had returned to obedience, and just as withdrawal of the Timurid troops, they were quickly back their former power. These clans and tribes sometimes were troublesome to the Ottoman Empires and Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Due to the remoteness of these regions of Timurid Capital and, more importantly, lack of permanent government administrations and organizations of the Timurid capital, following Amir Timur’s death, because of dynastic struggles among his Sons and Grandsons, the Turkmens under these conditions were increasing their power and then they had challenged the Timurid princes. The most important goals of this study has focused on investigation of their relationships and struggles. How and why Timurid Empire has begun to combat against Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens; what were the reasons for the failure of the Timurid deal with them, these are the questions that we try to find the answers in our study. -

From Beit Abhe to Angamali: Connections, Functions and Roles of the Church of the East’S Monasteries in Ninth Century Christian-Muslim Relations

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Cochrane, Steve (2014) From Beit Abhe to Angamali: connections, functions and roles of the Church of the East’s monasteries in ninth century Christian-Muslim relations. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13988/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Takhté Soleymān

Historical Site of Mirhadi Hoseini http://m-hosseini.ir ……………………………………………………………………………………… Takhté Soleymân Azar Goshnasp Fire-Temple Complex By Professor Dietrich Huff Takht-e Soleymân is an outstanding archeological site with substantial Sasanian and Il-khanid ruins in Azarbaijan province, between Bijâr and Šâhin-dež, about 30 km north-northeast of Takâb, with about 2, 200 m altitude, surrounded by mountain chains of more than 3000 m altitude. The place was obviously chosen for its natural peculiarity; an outcrop of limestone, about 60 m above the valley, built up by the sediments of the overflowing calcinating water of a thermal spring-lake (21° C) with about 80 m diameter and more than 60 m depth on the top of the hill (Damm). The place is mentioned in most of the medieval Oriental chronicles (e.g., Ebn Khordâdbeh, pp. 19, 119 ff.; Tabari, p. 866; Nöldeke, p. 100, n. 1; Bel'ami, p. 942, tr., II, p. 292; Ebn al-Faqih, pp. 246, 286; Mas'udi, ed. Pellat, sec. 1400, tr., IV, pp. 74 f; idem, Tanbih, p. 95; Abu Dolaf, pp. 31 ff.; Ferdowsi, pp. 111 ff.; Yâqut, Beirut, III, pp. 383-84, tr., pp. 367 ff; Qazvini, II, pp. 267; Hamd-Allâh Mostawfi, p. 64, tr., p. 69, who attributes its foundation to the Kayanid Kay Khosrow) and was visited and described repeatedly by western travelers and scholars since the 19th century (e.g., Ker Porter, pp. 557 ff.; Monteith, pp. 7 ff.; Rawlinson, pp. 46 ff.; Houtum Schindler, pp. 327 f.; Jackson, 1906, pp. 124 ff.). It was erroneously taken for a second Ecbatana (q.v.) by Henry Rawlinson, and defective Byzantine sources caused it to be confused with the great Atropatenian city of Ganzak (q.v.) and other places (Minorsky). -

Introduction to Understanding Principles and Features of Persian Garden Architecture

International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research (IJBR) ISSN 0976-2612, Online ISSN 2278–599X, Vol-7, Special Issue-Number4-June, 2016, pp497-507 http://www.bipublication.com Research Article Introduction to understanding principles and features of Persian garden architecture Hamed Hayaty*, Arezoo Abrisham Kar and Nafisetohidi pour Department of Architecture, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Research carried out about Persian gardens mainly consists of formation, type of used elements and their spatial structure and arrangement; while in addition to the above-mentioned, this article is trying to focus on the influence of Persian elements in formation of a Persian garden. Man-made has been in order to fulfill the material and spiritual needs of man and with peers on this issue; he has created the space to fulfill man's natural needs such as achieving peace. The vast landscape, spatial variety, sacred landscape, place of reflection and rectangular geometry are among them. Among the elements of nature, water and plants are more important than others and always affect the other elements. A smartly combination of water and plants inspace design of Persian gardens indicates that all three approaches of conceptual, functional and aesthetic are well-matched there and in fact, the emergence of these three concepts in the whole garden is the secret of Persian gardens stability. The main goal in research is to achieve understanding of elements of Iranian architecture and their arrangement in the formation of a Persian garden. The results indicate that Persian garden is a wise and perfection-oriented system that somehow has placed the natural elements of water and plantin itself that fulfills physical needs of the users and at the same time it also has attention to spiritual dimension.