An Analysis of Paternity and Filial Duty in Shakespeare's Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

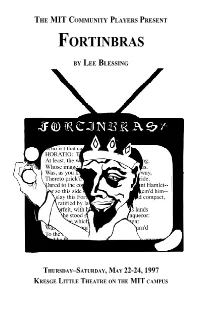

Fortinbras Program

THE MIT COMMUNITY PLAYERS PRESENT FORTINBRAS BY LEE BLESSING THURSDAY–SATURDAY, MAY 22-24, 1997 KRESGE LITTLE THEATRE ON THE MIT CAMPUS FORTINBRAS by Lee Blessing *Produced by special arrangement with Baker’s Plays The Persons of the Play Fortinbras ...................................... Steve Dubin Hamlet ........................................... Greg Tucker (S) Osric .............................................. Ian Dowell (A) Horatio........................................... Matt Norwood ’99 Ophelia .......................................... Erica Klempner (G) Claudius ........................................ Ben Dubrovsky (A) Gertrude ........................................ Anne Sechrest (affil) Laertes .......................................... Randy Weinstein (G) Polonius......................................... Peter Floyd (A, S) Polish Maiden 1............................. Alice Waugh (S) Polish Maiden 2............................. Anna Socrates Captain .......................................... Jim Carroll (A) English Ambassador ..................... Alice Waugh (S) Marcellus....................................... Eric Lindblad (G) Barnardo ....................................... Russell Miller ’00 The Scenes of the Play Act I: Elsinore — ten minute intermission — Act II: Still Elsinore (“S” indicates MIT staff member, “G” indicates graduate student, “A” indicates alumnus, and “affil” indicates affiliation with a member of the MIT community). Behind the Scenes Director............................................. Ronni -

Front.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Book Reviews 145 circumstances, as in his dealings with Polonius, and Rosencrantz and Guild- enstern. Did he not think he was killing the King when he killed Polonius? That too was a chance opportunity. Perhaps Hirsh becomes rather too confined by a rigorous logical analysis, and a literal reading of the texts he deals with. He tends to brush aside all alternatives with an appeal to a logical certainty that does not really exist. A dramatist like Shakespeare is always interested in the dramatic potential of the moment, and may not always be thinking in terms of plot. (But as I suggest above, the textual evidence from plot is ambiguous in the scene.) Perhaps the sentimentalisation of Hamlet’s character (which the author rightly dwells on) is the cause for so many unlikely post-renaissance interpretations of this celebrated soliloquy. But logical rigour can only take us so far, and Hamlet, unlike Brutus, for example, does not think in logical, but emotional terms. ‘How all occasions do inform against me / And spur my dull revenge’ he remarks. Anthony J. Gilbert Claire Jowitt. Voyage Drama and Gender Politics 1589–1642: Real and Imagined Worlds. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. Pp 256. For Claire Jowitt, Lecturer in Renaissance literature at University of Wales Aberystwyth, travel drama depicts the exotic and the foreign, but also reveals anxieties about the local and the domestic. In this her first book, Jowitt, using largely new historicist methodology, approaches early modern travel plays as allegories engaged with a discourse of colonialism, and looks in particular for ways in which they depict English concerns about gender, leadership, and national identity. -

Othello, Colin Powell, and Post-Racial Anachronisms

Othello, Colin Powell, and Post-Racial Anachronisms KYLE G RADY If progressive people, most of whom were white, could so blindly reproduce a version of the status quo and not “see” it, the thought of how racial politics would be played out “outside” this arena was horrifying. — bell hooks1 NWRITINGO THELLO, SHAKESPEARE PROFOUNDLY COMPLICATES ITS I OSTENSIBLE SOURCE, CINTHIO’ S G LI H ECATOMMITHI.This complex- ity is crafted through various additions and, as Coleridge famously observed, key subtractions.2 Removing Iago’s obvious motives, for example, develops a more mercurial and complicated villain, while also amplifying the senselessness of the final tragedy. In Cinthio’s tale, there is a satisfying denouement in which we learn that “all these events were told” by one “who knew the facts.”3 Shakespeare replaces this certitude with loose ends. Iago, the key to better grasping the play’s outcome, is resolutely uncommunicative once implicated, telling his accusers “What you know, you know. / From this time forth I never will speak word.”4 And, in what reads as a final longing for the clarity denied to the play, Othello voices an intractable charge: “Speak of me as I am” (5.2.351). As the drama’s lively critical afterlife demonstrates, there is a three-dimension- ality to Othello that thwarts attempts to fully meet this request. For their insight, I am sincerely grateful to the participants of the 2015 Shakespeare Association of America seminar “Early Modern Race / Ethnic / Diaspora Studies,” especially the seminar leaders, Kim F. Hall and Peter Erickson. Many thanks are also due to Michael Schoenfeldt and Valerie Traub for their generous feedback on this essay. -

View in Order to Answer Fortinbras’S Questions

SHAKESPEAREAN VARIATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK Steven Barrie A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor Dr. Kimberly Coates ii ABSTRACT Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor In this thesis, I examine six adaptations of the narrative known primarily through William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark to answer how so many versions of the same story can successfully exist at the same time. I use a homology proposed by Gary Bortolotti and Linda Hutcheon that explains there is a similar process behind cultural and biological adaptation. Drawing from the connection between literary adaptations and evolution developed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon, I argue there is also a connection between variation among literary adaptations of the same story and variation among species of the same organism. I determine that multiple adaptations of the same story can productively coexist during the same cultural moment if they vary enough to lessen the competition between them for an audience. iii For Pam. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Stephannie Gearhart, for being a patient listener when I came to her with hints of ideas for my thesis and, especially, for staying with me when I didn’t use half of them. Her guidance and advice have been absolutely essential to this project. I would also like to thank Kim Coates for her helpful feedback. She has made me much more aware of the clarity of my sentences than I ever thought possible. -

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’S Hamlet

The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mosley, Joseph Scott. 2017. The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Joseph Scott Mosley A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 © 2017 Joseph Scott Mosley Abstract The aim of the proposed thesis will be to examine the complex and compelling relationship between fathers and sons in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This study will investigate the difficult and challenging process of forming one’s own identity with its social and psychological conflicts. It will also examine how the transformation of the son challenges the traditional family model in concert or in discord with the predominant philosophy of the time. I will assess three father-son relationships in the play – King Hamlet and Hamlet, Polonius and Laertes, and Old Fortinbras and Fortinbras – which thematize and explore filial ambivalence and paternal authority through the act of revenge and mourning the death of fathers. -

Performing Prayer in Shakespeare's Sonnets

Access Provided by Harvard University at 01/28/13 5:08PM GMT Love’s Rites: Performing Prayer in Shakespeare’s Sonnets R H - Iaddressed to the beloved in Shakespeare’s Sonnets, the poet defends what seems like a penchant for rewriting the same poem over and over. Against the implicit accusations of his beloved, the poet compares his apologia in Sonnet 108 to a kind of spoken prayer, a highly ritualized and publicly performed devo- tional gesture: like prayers diuine, I must each day say ore the very same, Counting no old thing old, thou mine, I thine Euen as when first I hallowed thy faire name. (108.5–8)1 Echoing the beloved’s doubts, he asks whether repeated words have the capacity to express the depth of his love: “What’s new to speake, what now to register, / 6at may expresse my loue, or thy deare merit?” (ll. 3–4). 6ese questions have bothered more than just the poet’s friend. Generations of critics of the Sonnets have shared the beloved’s concern over the repetitive nature of the sequence’s devotional tropes, finding that the blandness of senti- ment betrays a desire that expresses itself “monotheistically, monogamously, monosyllabically, and monotonously.”2 Moreover, the Sonnets’ references to litur- I thank my colleagues at the Renaissance Colloquium at Harvard University for their responses to an earlier version of this essay. In particular, Misha Teramura offered valuable insight about my historical treatment of the antitheatrical tradition. Stephen Greenblatt read a later version of the manuscript in its entirety and clarified and strengthened my argument. -

Hamlet on the Screen Prof

Scholars International Journal of Linguistics and Literature Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Linguist Lit ISSN 2616-8677 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3468 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijll Review Article Hamlet on the Screen Prof. Essam Fattouh* English Department, Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria (Egypt) DOI: 10.36348/sijll.2020.v03i04.001 | Received: 20.03.2020 | Accepted: 27.03.2020 | Published: 07.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Prof. Essam Fattouh Abstract The challenge of adapting William Shakespeare‟s Hamlet for the screen has preoccupied cinema from its earliest days. After a survey of the silent Hamlet productions, the paper critically examines Asta Nielsen‟s Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance by noting how her main character is really a woman. My discussion of the modern productions of Shakespeare begins with a critical discussion of Lawrence Olivier‟s seminal production of 1948. The Russian Hamlet of 1964, directed by Grigori Kozintsev, is shown to combine a psychological interpretation of the hero without disregarding its socio-political context. The action-film genre deployed by Franco Zeffirelli in his 1990 adaptation of the play, through a moving performance by Mel Gibson, is analysed. Kenneth Branagh‟s ambitious and well-financed production of 1996 is shown to be somewhat marred by its excesses. Michael Almereyda‟s attempt to present Shakespeare‟s hero in a contemporary setting is shown to have powerful moments despite its flaws. The paper concludes that Shakespeare‟s masterpiece will continue to fascinate future generations of directors, actors and audiences. Keywords: Shakespeare – Hamlet – silent film – film adaptations – modern productions – Russian – Olivier – Branagh – contemporary setting. -

Language, Humour, Character, and Persona in Shakespeare

Language, Humour, Character, and Persona in Shakespeare Arthur Henry King The rst Oxford English Dictionary (hereafter OED)1 use of “character” as “a personality invested with distinctive attributes and qualities by a novelist or dramatist” is in Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749). OED does not list the Theophrastian2 use reected in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century character-sketches, for example Ben Jonson’s play, Every Man Out of His Humour, “the characters of the persons” (1599),3 those in the then current satires, and in translations and collections.4 Another OED entry under character, “personal appearance” (entry 10) correctly interprets Twelfth Night 1.02.51 “outward character”; but that phrase implies “inward character” too, and OED misinterprets Coriolanus 5.04.26 as the outward sense; but “I paint him in the character” refers to this description of Coriolanus (16-28): He no more remembers his mother now than an eight-year-old horse. The tartness of his face sours ripe grapes. When he walks, he moves like an engine, and the ground shrinks before his treading. He is able to pierce a corslet with his eye, talks like a knell, and his hum is a battery. He sits in his state, as a thing made for Alexander. What he bids be done is nish’d with his bidding. He wants nothing of a god but eternity and a heaven to throne in. I paint him in the character. There is no more mercy in him than there is milk in a male tiger. Compare Coriolanus 2.01.46-65, where Menenius sketches an ironical “character” of himself and makes “character” statements about the tribunes: I am known to be a humorous patrician, and one that loves a cup of hot wine with not a drop of allaying Tiber in’t; said to be something imperfect in favoring the rst complaint, hasty and tinder-like upon too trivial motion; one that converses more with the buttock of the night than with the forehead of the morning. -

Sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès

Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès To cite this version: Celine Savatier-Lahondès. Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory. Linguistics. Université Clermont Auvergne; University of Stirling, 2019. English. NNT : 2019CLFAL012. tel-02439401 HAL Id: tel-02439401 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02439401 Submitted on 14 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. University of Stirling – Université Clermont Auvergne Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Through the Shakespearean Repertory THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) AND DOCTEUR DES UNIVERSITÉS (DOCTORAT) BY CÉLINE SAVATIER LAHONDÈS Co-supervised by: Professor Emeritus John Drakakis Professor Emeritus Danièle Berton-Charrière Department of Arts and Humanities IHRIM Clermont UMR 5317 University of Stirling Faculté de Lettres et Sciences