PG Wodehouse and the Anachronism of Comic Form (Part One)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle The Dedication of a Memorial Stone to P G Wodehouse Friday 20th September 2019 6.15 pm HISTORICAL NOTE It is no bad thing to be remembered for cheering people up. As Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (1881–1975) has it in his novel Something Fresh, the gift of humour is twice blessed, both by those who give and those who receive: ‘As we grow older and realize more clearly the limitations of human happiness, we come to see that the only real and abiding pleasure in life is to give pleasure to other people.’ Wodehouse dedicated almost 75 years of his professional life to doing just that, arguably better—and certainly with greater application—than any other writer before or since. For he never deviated from the path of that ambition, no matter what life threw at him. If, as he once wrote, “the object of all good literature is to purge the soul of its petty troubles”, the consistently upbeat tone of his 100 or so books must represent one of the largest-ever literary bequests to human happiness by one man. This has made Wodehouse one of the few humourists we can rely on to increase the number of hours of sunshine in the day, helping us to joke unhappiness and seriousness back down to their proper size simply by basking in the warmth of his unique comic world. And that’s before we get round to mentioning his 300 or so song lyrics, countless newspaper articles, poems, and stage plays. The 1998 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary cited over 1,600 quotations from Wodehouse, second only to Shakespeare. -

Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World by DAVID MCDONOUGH

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 28 Number 2 Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World BY DAVID MCDONOUGH ecently I read that doing crossword puzzles helps to was “sires,” and the answer was “begets.” In Right Ho, R ward off dementia. It’s probably too late for me (I Jeeves (aka Brinkley Manor, 1934), Gussie Fink-Nottle started writing this on my calculator), but I’ve been giving interrogates G. G. Simmons, the prizewinner for Scripture it a shot. Armed with several good erasers, a thesaurus, knowledge at the Market Snodsbury Grammar School and my wife no more than a phone call away, I’ve been presentations. Gussie, fortified by a liberal dose of liquor- doing okay. laced orange juice, is suspicious of Master Simmons’s bona I’ve discovered that some of Wodehouse’s observations fides. on the genre are still in vogue. Although the Egyptian sun god (Ra) rarely rears its sunny head, the flightless “. and how are we to know that this has Australian bird (emu) is still a staple of the old downs and all been open and above board? Let me test you, acrosses. In fact, if you know a few internet terms and G. G. Simmons. Who was What’s-His-Name—the the names of one hockey player (Orr) and one baseball chap who begat Thingummy? Can you answer me player (Ott), you are in pretty good shape to get started. that, Simmons?” I still haven’t come across George Mulliner’s favorite clue, “Sir, no, sir.” though: “a hyphenated word of nine letters, ending in k Gussie turned to the bearded bloke. -

Index to Plum Lines 1980–2020

INDEX TO PLUM LINES 1980–2020 Guide to the Index: While there are all sorts of rules and guidelines on the subject of indexing, virtually none can be applied to the formidable task of indexing Plum Lines (and its predecessor, Comments in Passing), the quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society, which was founded in 1980. Too many variables confront the task’s indexer—not to mention a few too many errors in how issues were numbered over the years (see Index to the Index, below). Consequently, a new sort of index has been created in such a way (we hope) as to make it as easy as possible to use. Following are some guidelines. 1. Finding what you want: Whatever you are looking for, it should be possible to find it using our handy-dandy system of cross-referencing: • SUBJECTS are in BOLD CAPS followed by a list of the relevant articles. (See the list of Subject Headings, below.) • Authors and Contributors (note that some articles have both an author and a contributor) are listed in uppercase-lowercase bold, last name first, with a list of articles following the name. • Regular columns are simply listed in bold under their own titles rather than under a subject heading. 2. Locating the listed article: Any article listed in the index is followed by a series of numbers indicating its volume number, issue number, and page number. For example, one can find articles on Across the pale parabola: 14.2.17; 15.4.13 in Volume 14, Number 2, Page 17 and Volume 15, Number 4, Page 13. -

Autumn-Winter 2002

Beyond Anatole: Dining with Wodehouse b y D a n C o h en FTER stuffing myself to the eyeballs at Thanks eats and drinks so much that about twice a year he has to A giving and still facing several days of cold turkey go to one of the spas to get planed down. and turkey hash, I began to brood upon the subject Bertie himself is a big eater. He starts with tea in of food and eating as they appear in Plums stories and bed— no calories in that—but it is sometimes accom novels. panied by toast. Then there is breakfast, usually eggs and Like me, most of Wodehouse’s characters were bacon, with toast and marmalade. Then there is coffee. hearty eaters. So a good place to start an examination of With cream? We don’t know. There are some variations: food in Wodehouse is with the intriguing little article in he will take kippers, sausages, ham, or kidneys on toast the September issue of Wooster Sauce, the journal of the and mushrooms. UK Wodehouse Society, by James Clayton. The title asks Lunch is usually at the Drones. But it is invariably the question, “Why Isn’t Bertie Fat?” Bertie is consistent preceded by a cocktail or two. In Right Hoy Jeeves, he ly described as being slender, willowy or lissome. No describes having two dry martinis before lunch. I don’t hint of fat. know how many calories there are in a martini, but it’s Can it be heredity? We know nothing of Bertie’s par not a diet drink. -

Aunts Aren't What?

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 27 Number 3 Autumn 2006 Aunts Aren’t What? BY CHARLES GOULD ecently, cataloguing a collection of Wodehouse novels in translation, I was struck again by R the strangeness of the title Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen and by the sad history that seems to dog this title and its illustrators, who in my experience always include a cat. Wodehouse’s original title is derived from the dialogue between Jeeves and Bertie at the very end of the novel, in which Bertie’s idea that “the trouble with aunts as a class” is “that they are not gentlemen.” In context, this is very funny and certainly needs no explication. We are well accustomed to the “ungentlemanly” behavior of Aunt Agatha—autocratic, tyrannical, unreasoning, and unfair—though in this instance it’s the good and deserving Aunt Dahlia whose “moral code is lax.” But exalted to the level of a title and thus isolated, the statement A sensible Teutonic “aunts aren’t gentlemen” provokes some scrutiny. translation First, it involves a terrible pun—or at least homonymic wordplay—lost immediately on such lost American souls as pronounce “aunt” “ant” and “aren’t” “arunt.” That “aunt” and “aren’t” are homonyms is something of a stretch in English anyway, and to stretch it into a translation is hopeless. True, in “The Aunt and the Sluggard” (My Man Jeeves), Wodehouse wants us to pronounce “aunt” “ant” so that the title will remind us of the fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper; but “ants aren’t gentlemen” hasn’t a whisper of wit or euphony to recommend it to the ear. -

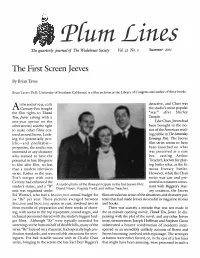

The First Screen Jeeves

Plum L in es The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Vol. 22 No. 2 Summer 2001 The First Screen Jeeves By Brian Taves Brian Taves (PhD, University of Southern California) is a film archivist at the Library of Congress and author of three books. t the end o f 1935,20th detective, and Chan was A Century-Fox bought the studio’s most popular the film rights to Thank “star” after Shirley Ton, Jeeves (along with a Temple. one-year option on the Like Chan, Jeeves had other stories) and the right been brought to the no to make other films cen tice of the American read tered around Jeeves. Look ing public in The Saturday ing for potentially pro Evening Post. The Jeeves lific—and profitable — film series seems to have properties, the studio was been launched on what interested in any character was perceived as a sure who seemed to have the bet, casting Arthur potential to lure filmgoers Treacher, known for play to film after film, no less ing butler roles, as the fa than a modern television mous literary butler. series. Earlier in the year, However, while the Chan Fox’s merger with 20th series was cast and pre Century had enhanced the sented in a manner conso A studio photo of the three principals in the first Jeeves film: studio’s status, and a CCB” nant with Biggers’s liter David Niven, Virginia Field, and Arthur Treacher. unit was organized under ary creation, the Jeeves Sol Wurtzel, who had a $6,000,000 annual budget for films revealed no sense of the situations and character pat 24 “Bs” per year. -

Wodehouse and the Baroque*1

Connotations Vol. 20.2-3 (2010/2011) Worcestershirewards: Wodehouse and the Baroque*1 LAWRENCE DUGAN I should define as baroque that style which deli- berately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its pos- sibilities and which borders on its own parody. (Jorge Luis Borges, The Universal History of Infamy 11) Unfortunately, however, if there was one thing circumstances weren’t, it was different from what they were, and there was no suspicion of a song on the lips. The more I thought of what lay before me at these bally Towers, the bowed- downer did the heart become. (P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters 31) A good way to understand the achievement of P. G. Wodehouse is to look closely at the style in which he wrote his Jeeves and Wooster novels, which began in the 1920s, and to realise how different it is from that used in the dozens of other books he wrote, some of them as much admired as the famous master-and-servant stories. Indeed, those other novels and stories, including the Psmith books of the 1910s and the later Blandings Castle series, are useful in showing just how distinct a style it is. It is a unique, vernacular, contorted, slangy idiom which I have labeled baroque because it is in such sharp con- trast to the almost bland classical sentences of the other Wodehouse books. The Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary describes the ba- roque style as “marked generally by use of complex forms, bold or- *For debates inspired by this article, please check the Connotations website at <http://www.connotations.de/debdugan02023.htm>. -

Feb 9, 2020 (PDF)

Eucharisc Liturgies (Mass) St. Edward Parish Office Saturday 8:15 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. Vigil Monday-Friday 8 a.m.—7 p.m. Sunday 7:30, 9:00 & 11:00 a.m., 1:00 Spanish & 5:30 p.m. Saturday & Sunday 8 a.m.—2 p.m. Weekday 8:15 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. (949) 496-1307 Holy Day Vigil 5:30 p.m. evening prior to the holy day Holy Day 8:15 a.m., 5:30 p.m. & 7:30 p.m. Spanish 33926 Calle La Primavera Dana Point, California 92629 Sacrament of Penance (Confession) Fax: (949) 496-1557 Monday 6:00—7:00 p.m. Saturday 4:00—5:00 p.m. www.stedward.com Confessions at San Felipe de Jesus Chapel First Friday 6:00—7:30 p.m. CLERGY You may also call a priest to schedule an appointment. Rev. Philip Smith Anoinng of the Sick/Emergency Administrator In the event of serious illness or medical emergency, contact the Parish office to arrange for Anoinng of the Sick and Eucharist. (949) 429-2880 [email protected] Sacrament of Bapsm Infant Bapsms are celebrated on the first and third Sundays of each month Rev. Marco Hernandez following catechesis for parents and godparents. Parents of infants should contact the Faith Formaon office (949) 496-6011 to enroll. Parochial Vicar (949) 429-2870 Celebraon of Chrisan Funerals [email protected] At the me of death, a family member should contact the Parish office to arrange the date and me for the funeral liturgy. -

Psmith in Pseattle: the 18Th International TWS Convention It’S Going to Be Psensational!

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 35 Number 4 Winter 2014 Psmith in Pseattle: The 18th International TWS Convention It’s going to be Psensational! he 18th biennial TWS convention is night charge for a third person, but Tless than a year away! That means there children under eighteen are free. are a lot of things for you to think about. Reservations must be made before While some of you avoid such strenuous October 8, 2015. We feel obligated activity, we will endeavor to give you the to point out that these are excellent information you need to make thinking as rates both for this particular hotel painless as possible. Perhaps, before going and Seattle hotels in general. The on, you should take a moment to pour a stiff special convention rate is available one. We’ll wait . for people arriving as early as First, clear the dates on your calendar: Monday, October 26, and staying Friday, October 30, through Sunday, through Wednesday, November 4. November 1, 2015. Of course, feel free to Third, peruse, fill out, and send come a few days early or stay a few days in the registration form (with the later. Anglers’ Rest (the hosting TWS chapter) does appropriate oof), which is conveniently provided with have a few activities planned on the preceding Thursday, this edition of Plum Lines. Of course, this will require November 29, for those who arrive early. There are more thought. Pour another stiff one. You will have to many things you will want to see and do in Seattle. -

Index to Wooster Sauceand by The

Index to Wooster Sauce and By The Way 1997–2020 Guide to this Index This index covers all issues of Wooster Sauce and By The Way published since The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) was founded in 1997. It does not include the special supplements that were produced as Christmas bonuses for renewing members of the Society. (These were the Kid Brady Stories (seven instalments), The Swoop (seven instalments), and the original ending of Leave It to Psmith.) It is a very general index, in that it covers authors and subjects of published articles, but not details of article contents. (For example, the author Will Cuppy (a contemporary of PGW’s) is mentioned in several articles but is only included in the index when an article is specifically about him.) The index is divided into three sections: I. Wooster Sauce and By The Way Subject Index Page 1 II. Wooster Sauce and By The Way Author Index Page 34 III. By The Way Issues in Number Order Page 52 In the two indexes, the subject or author (given in bold print) is followed by the title of the article; then, in bold, either the issue and page number, separated by a dash (for Wooster Sauce); or ‘BTW’ and its issue number, again separated by a dash. For example, 1-1 is Wooster Sauce issue 1, page 1; 20-12 is issue 20, page 12; BTW-5 is By The Way issue 5; and so on. See the table on the next page for the dates of each Wooster Sauce issue number, as well as any special supplements. -

2021 Qualifying Roles As of 4.15.21 for Website

2021 Jimmy Awards Qualifying Roles SHOWS FOR WHICH MORE THAN 6 ROLES ARE ELIGIBLE DUE TO THE ENSEMBLE NATURE OF THE MATERIAL Show Name Actor Actress Olive Ostrovsky, Logainne 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, The Leaf Coneybear, Chip Tolentino, William Barfee Shwartzandgrubenierre, Marcy Park, Rona Lisa Peretti Gomez Addams, Uncle Fester, Pugsley Addams, Morticia Addams, Wednesday Addams, Alice Addams Family, The Lucas Beineke, Mal Beineke Beineke Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 (cast may be expanded to Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 (cast may be As Thousands Cheer include as many roles as desired) expanded to include as many roles as desired) Avenue Q Princeton, Brian, Rod, Nicky Kate Monster, Christmas Eve, Gary Coleman Michael, Feargal, Billy, Corey Junior, Corey Tiffany, Cyndi, Eileen, Laura, Debbie, Miss Back to the 80's Senior, Mr. Cocker, Featured Male Brannigan Canterbury Tales Chaucer, Clerk, Host, Miller, Squire, Steward Nun, Prioress, The Sweetheart, Wife of Bath Children's Letters to God Ensemble Cast Ensemble Cast Hua Mulan, Pocahontas, Princess Disenchanted N/A Badroulbadour, Belle, Little Mermaid, Snow White, Rapunzel First Date Aaron, Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 Casey, Woman 1, Woman 2 Edna Turnblad, Link Larken, Seaweed, Corny Hairspray Tracy Turnblad, Velma, Motormouth Collins Norma Valverde, Heather Stovall, Kelli Hands on a Hardbody JD Drew, Benny Perkins, Greg Wilhote Mangrum Vanessa, Nina, Camila, Abuela Claudia, In the Heights Usnavi, Benny, Kevin Rosario Daniela Into the Woods Baker, Jack, The Wolf/Cinderella's Prince Baker's Wife, Witch, Cinderella, Little Red Is There Life After High School? Ensemble Ensemble Les Misérables Jean Valjean, Javert, Marius, Thenardier Fantine, Eponine, Cosette Frederick Egerman, Carl Magnus, Henrik Desiree Armfeldt, Madame Armfeldt, Little Night Music, A Egerman Charlotte, Anne Egerman, Petra The Queen Aggravain, Princess Winnifred, Once Upon a Mattress Prince Dauntless, Sir Harry, The Jester, Minstrel Lady Larkin Prom, The Barry Glickman, Trent Oliver, Mr. -

Ring for Jeeves: (Jeeves & Wooster) Free

FREE RING FOR JEEVES: (JEEVES & WOOSTER) PDF P. G. Wodehouse | 256 pages | 21 Dec 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099513926 | English | London, United Kingdom Ring for Jeeves (Jeeves, #10) by P.G. Wodehouse One upside of returning to night shifts is that I have more time to read. In my first two nights I got through a Hamish Macbeth novel and then on the third and fourth I read this. It is the s and the aristocracy must adapt to a changing world. Ring for Jeeves: (Jeeves & Wooster) is off at a special school learning life skills should the worst happen and he be forced to let Jeeves go and fend for himself. Jeeves is temporarily on loan with the Earl of Rowcester, Bill. Bill owns a crumbling mansion that is far too expensive to maintain and too large for his needs. Engaged to be married Bill has become a bookie, in disguise, assisted by Jeeves. The scheme has worked well and kept him afloat. En route to view the house Rosalind Spottsworth meets an old friend of her late husband, Captain Biggar, who carries a torch for her. Biggar is in hot pursuit of an unscrupulous bookmaker who has done a runner. Bill is encouraged by his sister to use his charms to try and sell the place, but this causes some jealousy and suspicion Ring for Jeeves: (Jeeves & Wooster) his fiancee. Can Jeeves help his new employer navigate the challenges of selling a house, sweet talking an old Ring for Jeeves: (Jeeves & Wooster) and keeping his fiancee happy? Can they hide from Biggar or come up with some way to find the money needed to pay him back? The farcical aspects of the story are handled well, slowly piling up around poor Bill but never becoming too ridiculous.