Imaginaries of Development Through Extr...Um' and the Present View Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Civil Society Works for a Democracy That Is Not Only More Representative

‘Civil society works for a democracy that is not only more representative but also more participatory’ CIVICUS speaks to Ramiro Orias, a Bolivian lawyer and human rights defender. Orias is a program officer with the Due Process of Law Foundation and a member and former director of Fundación Construir, a Bolivian CSO aimed at promoting citizen participation process for the strengthening of democracy and equal access to plural, equitable, transparent and independent judicial institutions. Q: A few days ago a national protest against the possibility of a new presidential re-election took place in Bolivia. Do you see President Evo Morales’ new re-election attempt as an example of democratic degradation? The president’s attempt to seek another re-election is part of a broader process of erosion of democratic civic space that has resulted from the concentration of power. The quest for a new presidential re-election requires a reform of the 2009 Constitution (which was promulgated by President Evo Morales himself). Some of the provisions introduced into the new constitutional text were very progressive; they indeed implied significant advances in terms of rights and guarantees. On the other hand, political reforms aimed at consolidating the newly acquired power were also introduced. For instance, there was a change in the composition and political balances within the Legislative Assembly that was aimed at over-representing the majority; the main authorities of the judiciary were dismissed before the end of their terms (the justices of the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Tribunal were put to trial and forced to resign) and an election system for magistrates was established. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

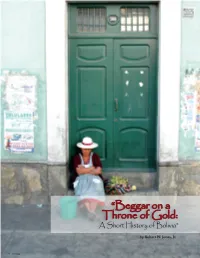

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Iv BOLIVIA the Top of the World

iv BOLIVIA The top of the world Bolivia takes the breath away - with its beauty, its geographic and cultural diversity, and its lack of oxygen. From the air, the city of La Paz is first glimpsed between two snowy Andean mountain ranges on either side of a plain; the spread of the joined-up cities of El Alto and La Paz, cradled in a huge canyon, is an unforgettable sight. For passengers landing at the airport, the thinness of the air induces a mixture of dizziness and euphoria. The city's altitude affects newcomers in strange ways, from a mild headache to an inability to get up from bed; everybody, however, finds walking up stairs a serious challenge. The city's airport, in the heart of El Alto (literally 'the high place'), stands at 4000 metres, not far off the height of the highest peak in Europe, Mont Blanc. The peaks towering in the distance are mostly higher than 5000m, and some exceed 6000m in their eternally white glory. Slicing north-south across Bolivia is a series of climatic zones which range from tropical lowlands to tundra and eternal snows. These ecological niches were exploited for thousands of years, until the Spanish invasion in the early sixteenth century, by indigenous communities whose social structure still prevails in a few ethnic groups today: a single community, linked by marriage and customs, might live in two or more separate climes, often several days' journey away from each other on foot, one in the arid high plateau, the other in a temperate valley. -

The XXI Century Socialism in the Context of the New Latin American Left Civilizar

Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas ISSN: 1657-8953 [email protected] Universidad Sergio Arboleda Colombia Ramírez Montañez, Julio The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, vol. 17, núm. 33, julio-diciembre, 2017, pp. 97- 112 Universidad Sergio Arboleda Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=100254730006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas 17 (33): 97-112, Julio-Diciembre de 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22518/16578953.902 The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left1 El socialismo del siglo XXI en el contexto de la nueva izquierda latinoamericana Recibido: 27 de juniol de 2016 - Revisado: 10 de febrero de 2017 – Aceptado: 10 de marzo de 2017. Julio Ramírez Montañez2 Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to present an analytical approach of the self- proclaimed “new socialism of the XXI Century” in the context of the transformations undertaken by the so-called “Bolivarian revolution”.The reforms undertaken by referring to the ideology of XXI century socialism in these countries were characterized by an intensification of the process of transformation of the state structure and the relations between the state and society, continuing with the nationalization of sectors of the economy, the centralizing of the political apparatus of State administration. -

Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo

www.ssoar.info Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Roniger, L., & Senkman, L. (2019). Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 11(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X19843008 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Journal of Politics in j Latin America Research Article Journal of Politics in Latin America 2019, Vol. 11(1) 3–22 Fuel for Conspiracy: ª The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Suspected Imperialist sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1866802X19843008 Plots and the Chaco War journals.sagepub.com/home/pla Luis Roniger1 and Leonardo Senkman2 Abstract Conspiracy discourse interprets the world as the object of sinister machinations, rife with opaque plots and covert actors. With this frame, the war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Northern Chaco region (1932–1935) emerges as a paradigmatic conflict that many in the Americas interpreted as resulting from the conspiracy man- oeuvres of foreign oil interests to grab land supposedly rich in oil. At the heart of such interpretation, projected by those critical of the fratricidal war, were partial and extrapolated facts, which sidelined the weight of long-term disputes between these South American countries traumatised by previous international wars resulting in humiliating defeats and territorial losses, and thus prone to welcome warfare to bolster national pride and overcome the memory of past debacles. -

Oil Nationalizations in Bolivia and Mexico Established a Period of Tension and Conflict with U.S

The Oil Nationalizations in Bolivia (1937) and Mexico (1938): a comparative study of asymmetric confrontations with the United States Fidel Pérez Flores IREL/UnB [email protected] Clayton M. Cunha Filho UFC [email protected] 9o Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia Política ¿Democracias en Recesión? Montevideo, 26-28 de julio de 2017 2 The Oil Nationalizations in Bolivia (1937) and Mexico (1938): a comparative study of asymmetric confrontations with the United States I. Introduction Between 1937 and 1942, oil nationalizations in Bolivia and Mexico established a period of tension and conflict with U.S. companies and government. While in both cases foreign companies were finally expelled from host countries in what can be seen as a starting point for the purpose of building a national oil industry, a closer look at political processes reveal that the Bolivian government was less successful than the Mexican in maintaining its initial stand in face of the pressure of both the foreign company and the U.S. Government. Why, despite similar contextual conditions, was it more difficult for Bolivian than for Mexican officials to deal with the external pressures to end their respective oil nationalization controversy? The purpose of this study is to explore, in light of the Mexican and Bolivian oil nationalizations of the 1930’s, how important domestic politics is in less developed countries to maintain divergent preferences against more powerful international actors. This paper focuses on the political options of actors from peripheral countries in making room for their own interests in an international system marked by deep asymmetries. We assume that these options are in part the product of processes unfolding inside national political arenas. -

— — the Way We Will Work

No. 03 ASPEN.REVIEW 2017 CENTRAL EUROPE COVER STORIES Edwin Bendyk, Paul Mason, Drahomíra Zajíčková, Jiří Kůs, Pavel Kysilka, Martin Ehl POLITICS Krzysztof Nawratek ECONOMY Jacques Sapir CULTURE Olena Jennings INTERVIEW Alain Délétroz Macron— Is Not 9 771805 679005 No. 03/2017 No. 03/2017 Going to Leave Eastern Europe Behind — e-Estonia:— The Way We Will Work We Way The Between Russia and the Cloud The Way We Will Work About Aspen Aspen Review Central Europe quarterly presents current issues to the general public in the Aspenian way by adopting unusual approaches and unique viewpoints, by publishing analyses, interviews, and commentaries by world-renowned professionals as well as Central European journalists and scholars. The Aspen Review is published by the Aspen Institute Central Europe. Aspen Institute Central Europe is a partner of the global Aspen network and serves as an independent platform where political, business, and non-prof-it leaders, as well as personalities from art, media, sports and science, can interact. The Institute facilitates interdisciplinary, regional cooperation, and supports young leaders in their development. The core of the Institute’s activities focuses on leadership seminars, expert meetings, and public conferences, all of which are held in a neutral manner to encourage open debate. The Institute’s Programs are divided into three areas: — Leadership Program offers educational and networking projects for outstanding young Central European professionals. Aspen Young Leaders Program brings together emerging and experienced leaders for four days of workshops, debates, and networking activities. — Policy Program enables expert discussions that support strategic think- ing and interdisciplinary approach in topics as digital agenda, cities’ de- velopment and creative placemaking, art & business, education, as well as transatlantic and Visegrad cooperation. -

November 14, 2019, Vol. 61, No. 46

El juicio político 12 Golpe en Bolivia 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 61 No. 46 Nov. 14, 2019 $1 U.S.-backed coup in Bolivia Indigenous, workers resist By John Catalinotto “opened the doors to absolute impu- Nov. 11—In a message from his base east of the country. Since Oct. 20, when nity for those who are able to exercise in the Chapare region in central Bolivia, Morales won re-election, these gangs have Nov. 12— From La Paz, journalist power.” But, Teruggi adds, “[The] half President Evo Morales said on the eve- attacked and beaten pro-Morales elected Marco Teruggi writes that 24 hours after of the country that voted for [President] ning of Nov. 10: “I want to tell you, broth- political leaders, burning their homes and the U.S.-backed coup in Bolivia, “There Evo Morales exists and will not stand ers and sisters, that the fight does not end offices across the country. is no formal government, but there is idly by.” Formal and informal organi- here. We will continue this fight for equal- Immediately, the imperialist-con- the power of arms.” (pagina12.org) zations of Indigenous peoples, campesi- ity, for peace.” (Al Jazeera, Nov. 11) trolled media worldwide tried to give Police and soldiers patrol at the behest nos and workers are blockading roads, Earlier that day, a fascist-led coup their unanimous spin to the event, slan- of the coup leaders, while fascistic gangs setting up self-defense units, and call- backed by the Bolivian police and mil- dering the Morales government and roam, beat and burn, the coup having ing for “general resistance to the coup itary, and receiving the full support of its Movement toward Socialism (MAS) d’état throughout the coun- U.S. -

Casaroes the First Y

LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER GLOBAL THE NEW AND AMERICA LATIN Antonella Mori Do, C. Quoditia dium hucient. Ur, P. Si pericon senatus et is aa. vivignatque prid di publici factem moltodions prem virmili LATIN AMERICA AND patus et publin tem es ius haleri effrem. Nos consultus hiliam tabem nes? Acit, eorsus, ut videferem hos morei pecur que Founded in 1934, ISPI is THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER an independent think tank alicae audampe ctatum mortanti, consint essenda chuidem Dangers and Opportunities committed to the study of se num ute es condamdit nicepes tistrei tem unum rem et international political and ductam et; nunihilin Itam medo, nondem rebus. But gra? in a Multipolar World economic dynamics. Iri consuli, ut C. me estravo cchilnem mac viri, quastrum It is the only Italian Institute re et in se in hinam dic ili poraverdin temulabem ducibun edited by Antonella Mori – and one of the very few in iquondam audactum pero, se issoltum, nequam mo et, introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research et vivigna, ad cultorum. Dum P. Sp. At fuides dermandam, activities with a significant mihilin gultum faci pro, us, unum urbit? Ublicon tem commitment to training, events, Romnit pari pest prorimis. Satquem nos ta nostratil vid and global risk analysis for pultis num, quonsuliciae nost intus verio vis cem consulicis, companies and institutions. nos intenatiam atum inventi liconsulvit, convoliis me ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach perfes confecturiae audemus, Pala quam cumus, obsent, made possible by a research quituam pesis. Am, quam nocae num et L. Ad inatisulic team of over 50 analysts and tam opubliciam achum is. -

Bolivia: Latin America's Experiment in Grassroots Democracy

Bolivia: Latin America's Experiment in Grassroots Democracy A NEW ALLIANCE OF DEMOCRATICALLY-ELECTED GOVERNMENTS with a range of socialist programs is sweeping Latin America. New trade agreements that embrace the possibility of pan-regional alliances are being forged. Venezuela, Ecuador, and to a significant extent Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and Brazil articulate some policies of uplifting the poor and challenging US and neoliberal hegemony. Other nations are making their way to this list. Among these synergistic movements, no country in Latin America is better positioned to become a democratic socialist state than Bolivia. It has all the potential elements of a powerful bottom-up people's movement, rich in cultural and organizational forms. It has the poorest and most indigenous population in South America, has overthrown more governments than any other nation in the hemisphere, and has sufficient if yet untapped natural resources, if distributed fairly, to dramatically improve the lot of its people. It likely has the most varied and effective grassroots, egalitarian organizations in the world.1 In December 2005, that movement elected its first indigenous president, Evo Morales, and a national assembly majority organized through the electoral party Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS — movement toward socialism). Many Bolivian activists speak of a "radical humanism" rather than a strictly class-based society, a multi- leader, multi-movement power and "pluri-national" society that derives ideas and strength from its multiplicity; many seek a movement that exerts control rather than a party or government that seizes control.2 All of these goals are contested. The struggle for the future of Bolivia poses the most fundamental questions facing socialist transformation. -

Evo Morales and Electoral Fraud in Bolivia: a Natural Experiment Estimate Diego Escobari Gary A

1 Evo Morales and Electoral Fraud in Bolivia: A Natural Experiment Estimate Diego Escobari Gary A. Hoover Abstract—This paper exploits a natural experiment based on a disruption in the official preliminary vote counting system to identify and estimate the size of electoral fraud in the 2019 Bolivian presidential elections. The results show evidence of a statistically significant electoral case of fraud that increased the votes of the incumbent Movimiento al Socialismo and decreased the votes of the runner up Comunidad Ciudadana. We estimate that the extent of the fraud is at least 2.67% of the valid votes, sufficient to change the outcome of the election. We validate our results with pseudo-outcomes on a placebo analysis. We also allow for heterogeneous voting preferences across different geographical regions (e.g., rural vs. urban) and document how fraudulent polling stations were hidden in the final reporting of the votes. Resumen—Este art´ıculo utiliza un experimento natural basado en la ruptura del sistema oficial de conteo rapido´ de votos para identificar y cuantificar el fraude en las elecciones presidenciales de 2019 en Bolivia. Los resultados muestran evidencia de un fraude electoral estad´ısticamente significativo que incremento´ los votos del partido de gobierno Movimiento al Socialismo y disminuyo´ los votos del principal partido opositor Comunidad Ciudadana. Estimamos que el fraude fue de al menos 2,67% de los votos validos,´ suficiente como para cambiar el resultado final de las elecciones. Validamos nuestros resultados con pseudo-efectos en un analisis´ de placebo. Tambien´ controlamos por preferencias de voto heterogeneas´ en diferentes regiones geograficas´ (e.g., rural vs. -

(Y Salvar) La Nación: El Socialismo Militar Boliviano Revisitado T'inkazos

T'inkazos. Revista Boliviana de Ciencias Sociales ISSN: 1990-7451 [email protected] Programa de Investigación Estratégica en Bolivia Bolivia Stefanoni, Pablo Rejuvenecer (y salvar) la nación: el socialismo militar boliviano revisitado T'inkazos. Revista Boliviana de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 37, 2015 Programa de Investigación Estratégica en Bolivia La Paz, Bolivia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=426141579005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Rejuvenecer (y salvar) la nación: el socialismo militar boliviano revisitado To rejuvenate (and save) the nation: Bolivian military socialism revisited Pablo Stefanoni1 , número 37, 2015 pp. 49-64, ISSN 1990-7451 Fecha de recepción: mayo de 2015 Fecha de aprobación: junio de 2015 Versión final: junio de El presente artículo analiza las especificidades del antiliberalismo boliviano de la década de 1930 centrando la mirada en la experiencia socialista militar. El autor propone reponer la atmósfera ideológica, analizar sus tensiones y aprehender las particularidades de este experimento estatal, vinculado íntimamente a la derrota bélica a manos paraguayas, que puso en juego un lenguaje de cambio que incluyó visiones organicistas de la nación que buscaron dejar atrás la democracia liberal. Palabras clave: socialismo militar / izquierdas / Guerra del Chaco/ democracia funcional / vitalismo / David Toro / Germán Busch / Bolivia This article analyses the specificities of Bolivian anti-libera s of this state experiment which was closely linked to the military defeat in the war against Paraguay, a historical landmark that triggered a discourse of change pregnant with organicistic visions of the nation and a strong rejection of liberal democracy.