Iv BOLIVIA the Top of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Social Council

70+6'& ' 0#6+105 'EQPQOKECP5QEKCN Distr. %QWPEKN GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/80/Add.3 17 November 2003 ENGLISH Original: SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Item 15 of the provisional agenda INDIGENOUS ISSUES Human rights and indigenous issues Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Mr. Rodolfo Stavenhagen, submitted in accordance with Commission resolution 2003/56 Addendum MISSION TO CHILE* * The executive summary of this report will be distributed in all official languages. The report itself, which is annexed to the summary, will be distributed in the original language and in English. GE.03-17091 (E) 040304 090304 E/CN.4/2004/80/Add.3 page 2 Executive summary This report is submitted in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 2003/56 and covers the official visit to Chile by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, which took place between 18 and 29 July 2003. In 1993, Chile adopted the Indigenous Peoples Act (Act No. 19,253), in which the State recognizes indigenous people as “the descendants of human groups that have existed in national territory since pre-Colombian times and that have preserved their own forms of ethnic and cultural expression, the land being the principal foundation of their existence and culture”. The main indigenous ethnic groups in Chile are listed as the Mapuche, Aymara, Rapa Nui or Pascuense, Atacameño, Quechua, Colla, Kawashkar or Alacaluf, and Yámana or Yagán. Indigenous peoples in Chile currently represent about 700,000 persons, or 4.6 per cent of the population. -

LARC Resources on Indigenous Languages and Peoples of the Andes Film

LARC Resources on Indigenous Languages and Peoples of the Andes The LARC Lending Library has an extensive collection of educational materials for teacher and classroom use such as videos, slides, units, books, games, curriculum units, and maps. They are available for free short term loan to any instructor in the United States. These materials can be found on the online searchable catalog: http://stonecenter.tulane.edu/pages/detail/48/Lending-Library Film Apaga y Vamonos The Mapuche people of South America survived conquest by the Incas and the Spanish, as well as assimilation by the state of Chile. But will they survive the construction of the Ralco hydroelectric power station? When ENDESA, a multinational company with roots in Spain, began the project in 1997, Mapuche families living along the Biobio River were offered land, animals, tools, and relocation assistance in return for the voluntary exchange of their land. However, many refused to leave; some alleged that they had been marooned in the Andean hinterlands with unsafe housing and, ironically, no electricity. Those who remained claim they have been sold out for progress; that Chile's Indigenous Law has been flouted by then-president Eduardo Frei, that Mapuches protesting the Ralco station have been rounded up and prosecuted for arson and conspiracy under Chile's anti-terrorist legislation, and that many have been forced into hiding to avoid unfair trials with dozens of anonymous informants testifying against them. Newspaper editor Pedro Cayuqueo says he was arrested and interrogated for participating in this documentary. Directed by Manel Mayol. 2006. Spanish w/ English subtitles, 80 min. -

Report on the Work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team 2018

Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team 2018 1 Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team - 2018 Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team - 2018 Partnerships and South-South Cooperation Division, Advocacy Unit (DPSA) Background Since the creation of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team in DPSA in June 2014, the strategy of the team has been to position an agenda of work within FAO, rooted in the 2007 UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and to set in motion the implementation of the 2010 FAO Policy on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. The work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team is the result of constant interactions and discussions with indigenous peoples’ representatives. The joint workplan emanating from the 2015 meeting between indigenous representatives and FAO was structured around 6 pillars of work (Advocacy and capacity development; Coordination; Free Prior and Informed Consent; Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests and the Voluntary Guidelines on Small-Scale Fisheries; Indigenous Food Systems; and Food Security Indicators). Resulting from the discussions with indigenous youth in April 2017, a new relevant pillar was outlined related to intergenerational exchange and traditional knowledge in the context of climate change and resilience. In 2017, the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team shifted from advocacy, particularly internal to the Organization, to consolidation and programming. Through a two-year programme of work encompassing the 6+1 pillars of work and the thematic areas – indigenous women and indigenous youth, the Team succeeded in leveraging internal support and resources to implement several of the activities included in the programme of work for 2018. -

Number of Plant Species That Correspond with Data Obtained from at Least Two Other Participants

Promotor: Prof. Dr. ir. Patrick Van Damme Faculty of Bioscience Engineering Department of Plant Production Laboratory of Tropical and Sub-Tropical Agriculture and Ethnobotany Coupure links 653 B-9000 Gent, Belgium ([email protected]) Co-Promotor: Dr. Ina Vandebroek Institute of Economic Botany The New York Botanical Garden Bronx River Parkway at Fordham Road Bronx, New York 10458, USA ([email protected]) Chairman of the Jury: Prof. Dr. ir. Norbert De Kimpe Faculty of Bioscience Engineering Department of Organic Chemistry Coupure links 653 B-9000 Gent, Belgium ([email protected]) Members of the Jury: Prof. Dr. ir. Christian Vogl Prof. Dr. Paul Goetghebeur University of Natural Resources and Faculty of Science Applied Life Sciences Department of Biology Institut für Ökologischen Landbau K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 Gregor Mendelstrasse 33 B-9000 Gent, Belgium A-1180, Vienna, Austria ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Prof. Dr. Mieke Verbeken Prof. Dr. ir. François Malaisse Faculty of Science Faculté Universitaire des Sciences Department of Biology Agronomiques K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 Laboratoire d’Ecologie B-9000 Gent, Belgium Passage des Déportés, 2 ([email protected]) B-5030 Gembloux, Belgium ([email protected]) Prof. Dr. ir. Dirk Reheul Faculty of Bioscience Engineering Department of Plant Production Coupure links 653 B-9000 Gent, Belgium ([email protected]) Dean: Prof. Dr. ir. Herman Van Langenhove Rector: Prof. Dr. Paul Van Cauwenberge THOMAS EVERT QUANTITATIVE ETHNOBOTANICAL RESEARCH -

Eastern Woodland Indians Living in the Northeastern United States Were the First Known People to Have Used the Sap of Maple Trees

Eastern Woodland Indians living in the northeastern United States were the first known people to have used the sap of maple trees. 1 Maple syrup is made from the xylem sap of maple trees and is now a common food all around the country. 1 Native Americans from many regions chewed the sap from trees to freshen their breath, promote dental health, and address a variety of other health issues. 2 The sap of the sapodilla tree, known as chicle, was chewed by native peoples in Central America. It was used as the base for the first mass-produced chewing gum and is still used by some manufacturers today. 2 Inuits, indigenous peoples of the Arctic, carved goggles out of wood, bone, or shell to protect their eyes from the blinding reflection of the sun on the snow. 3 Goggles made from wood, bone, or shell were a precursor to modern sunglasses and snow goggles, which protect the eyes from ultraviolet rays. 3 Aztecs and Mayans living in Mesoamerica harvested sap from what we call the “rubber tree” and made an important contribution to team sports. 4 The Olmec, Maya, and Aztec peoples of Mesoamerica used the sap from certain trees to make rubber balls. The Maya still make them today! These balls are considered a precursor to the bouncing ball used in modern games. 4 Native peoples in Mesoamerica developed a method of cooking ground corn with alkaline substances. This method produces a chemical reaction that releases niacin. Niacin softens the corn, increases its protein content, and prevents against a skin disease called pellagra. -

Halpern, Robert; Fisk, David Preschool Education in Latin America

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 208 941 PS 012 384 AUTHOR Halpern, Robert; Fisk, David TITLE Preschool Education in Latin America: A Survey Report from the Andean Region. Volume I: Summary Report. INSTITUTICN High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, Ypsilanti, Mich. SPONS AGENCY Agency for International Development (Dept. of State), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 168p.: Page 101 is missing from the original document and is not available. EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Community Involvement; Cost Effectiveness; Cross Cultural Studies; *Decision Making; *Economic Factors; Educational Objectives: Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; Government Role: *International Organizations; *Latin Americans; Parent Participation; *Policy Formation; *Preschool Education; Program Development; Program Lvaluation IDF4TIFIERS *Andean Countries; Bolivia; Chile; Colombia ABSTRACT This report records survey results of preschool education programs serving children ages 3 through 6 and their families in Bolivia, Chile, and Colombia. Programs surveyed were primarily designed to reach the poorest sectors of the popu.i.ation, focused on improving the young child's psychomotor and social development, and utilized various educational intervention techniques in the home or center to provide services. The central objectives of the survey were to describe from a public policy perspective the major preschool education activities in the host countries; to document the nature, objectives, and central variab.Les constituting the "decision -

Land Is Life: the Struggle of the Quechua People to Gain Their Land Rights

BRIEFING NOTE 26 SEPTEMBER 2016 Teddy Guerra, the leader of the Quechua community of Nuevo Andoas, shows the impact of oil contamination on the ancestral lands of his people. Photo: Julie Barnes/Oxfam LAND IS LIFE The struggle of the Quechua people to gain their land rights ‘This land was inherited from our fathers. Now it is our time, and soon it will be the next generation’s time. But we live with the knowledge that the government might again license our territory out to oil companies at any time. For us, it’s important to be given formal land titles, not so that we can feel like owners, but to protect our territory.’ –Teddy Guerra Magin, indigenous leader and farmer, Nuevo Andoas 1 SUMMARY: THE QUECHUA PEOPLE’S STRUGGLE TO DEFEND THEIR TERRITORY In the absence of a title to their territories, the future of the indigenous people of Nuevo Andoas community and the wider Loreto region of northern Peru is under threat. Since the early 1970s, when the government gave multinational companies permission to exploit the region’s oil reserves, indigenous people have suffered the health and environmental consequences of a poorly regulated extractives industry. Repeated contamination of their land and rivers has caused illness and deaths, particularly among children. People’s livelihoods, which are based on cultivation and hunting and fishing, have also been seriously affected. The land on which the oil companies have been operating – known by the government and companies as ‘Block 192’ – covers the upper part of the basin of the Pastaza, Corrientes and Tigre rivers, which are all ancestral territories of indigenous populations. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

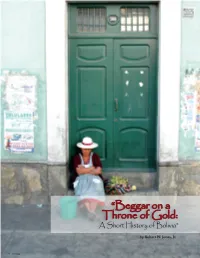

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

278550Paper0bolivia1case1ed

T H E W O R L D B A N K Public Disclosure Authorized Country Studies Country Studies are part of the Education Reform and Education Reform and Management Publication Series Management (ERM) Publication Series, which also in- Vol. II No. 2 November 2003 cludes Technical Notes and Policy Studies. ERM publica- tions are designed to provide World Bank client coun- tries with timely insight and analysis of education reform efforts around the world. ERM Country Studies examine how individual countries have successfully launched and The Bolivian Education Reform 1992-2002: implemented significant reforms of their education sys- Case Studies in Large-Scale Education Reform tems. ERM publications are under the editorial supervi- sion of the Education Reform and Management Thematic Group, part of the Human Development Network—Educa- tion at the World Bank. Any views expressed or implied should not be interpreted as official positions of the World Bank. Electronic versions of this document are available Public Disclosure Authorized on the ERM website listed below. Manuel E. Contreras Maria Luisa Talavera Simoni EDUCATION REFORM AND MANAGEMENT TEAM Human Development Network—Education The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Knowledge Coordinator: Barbara Bruns Research Analyst: Akanksha A. Marphatia WEB: www.worldbank.org/education/ globaleducationreform Public Disclosure Authorized E-MAIL: [email protected] TELEPHONE: (202) 473-1825 FACSIMILE: (202) 522-3233 Public Disclosure Authorized T H E W O R L D B A N K Country Studies Country Studies are part of the Education Reform and Education Reform and Management Publication Series Management (ERM) Publication Series, which also in- Vol. -

Vegetation and Climate Change on the Bolivian Altiplano Between 108,000 and 18,000 Years Ago

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 1-1-2005 Vegetation and climate change on the Bolivian Altiplano between 108,000 and 18,000 years ago Alex Chepstow-Lusty Florida Institute of Technology, [email protected] Mark B. Bush Florida Institute of Technology Michael R. Frogley Florida Institute of Technology, 150 West University Boulevard, Melbourne, FL Paul A. Baker Duke University, [email protected] Sherilyn C. Fritz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Chepstow-Lusty, Alex; Bush, Mark B.; Frogley, Michael R.; Baker, Paul A.; Fritz, Sherilyn C.; and Aronson, James, "Vegetation and climate change on the Bolivian Altiplano between 108,000 and 18,000 years ago" (2005). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 30. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Alex Chepstow-Lusty, Mark B. Bush, Michael R. Frogley, Paul A. Baker, Sherilyn C. Fritz, and James Aronson This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ geosciencefacpub/30 Published in Quaternary Research 63:1 (January 2005), pp. -

Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo

www.ssoar.info Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Roniger, L., & Senkman, L. (2019). Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 11(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X19843008 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Journal of Politics in j Latin America Research Article Journal of Politics in Latin America 2019, Vol. 11(1) 3–22 Fuel for Conspiracy: ª The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Suspected Imperialist sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1866802X19843008 Plots and the Chaco War journals.sagepub.com/home/pla Luis Roniger1 and Leonardo Senkman2 Abstract Conspiracy discourse interprets the world as the object of sinister machinations, rife with opaque plots and covert actors. With this frame, the war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Northern Chaco region (1932–1935) emerges as a paradigmatic conflict that many in the Americas interpreted as resulting from the conspiracy man- oeuvres of foreign oil interests to grab land supposedly rich in oil. At the heart of such interpretation, projected by those critical of the fratricidal war, were partial and extrapolated facts, which sidelined the weight of long-term disputes between these South American countries traumatised by previous international wars resulting in humiliating defeats and territorial losses, and thus prone to welcome warfare to bolster national pride and overcome the memory of past debacles. -

Seasonal Patterns of Atmospheric Mercury in Tropical South America As Inferred by a Continuous Total Gaseous Mercury Record at Chacaltaya Station (5240 M) in Bolivia

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 3447–3472, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-3447-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Seasonal patterns of atmospheric mercury in tropical South America as inferred by a continuous total gaseous mercury record at Chacaltaya station (5240 m) in Bolivia Alkuin Maximilian Koenig1, Olivier Magand1, Paolo Laj1, Marcos Andrade2,7, Isabel Moreno2, Fernando Velarde2, Grover Salvatierra2, René Gutierrez2, Luis Blacutt2, Diego Aliaga3, Thomas Reichler4, Karine Sellegri5, Olivier Laurent6, Michel Ramonet6, and Aurélien Dommergue1 1Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement, Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IRD, Grenoble INP, Grenoble, France 2Laboratorio de Física de la Atmósfera, Instituto de Investigaciones Físicas, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, La Paz, Bolivia 3Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research/Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, 00014, Finland 4Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA 5Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, Laboratoire de Météorologie Physique, UMR 6016, Clermont-Ferrand, France 6Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE-IPSL (CEA-CNRS-UVSQ), Université Paris-Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France 7Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA Correspondence: Alkuin Maximilian Koenig ([email protected]) Received: 22 September 2020 – Discussion started: 28 October 2020 Revised: 20 January 2021 – Accepted: 21 January 2021 – Published: 5 March 2021 Abstract. High-quality atmospheric mercury (Hg) data are concentrations were linked to either westerly Altiplanic air rare for South America, especially for its tropical region. As a masses or those originating from the lowlands to the south- consequence, mercury dynamics are still highly uncertain in east of CHC.