Un Modelo Computacional Del Suspense En Entornos Narrativos E Interactivos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

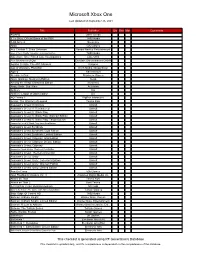

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Threat Simulation in Virtual Limbo Preprint

This is a preprint of the article “Threat simulation in virtual limbo: An evolutionary approach to horror video games” by Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen and Mathias Clasen, Aarhus University. The final, published version has been published in the Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds and is available at https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.11.2.119_1. Page 2 of 33 Threat Simulation in Virtual Limbo: An Evolutionary Approach to Horror Video Games Keywords: horror, Limbo, game studies, evolution, simulation, evolutionary psychology Abstract Why would anyone want to play a game designed to scare them? We argue that an alliance between evolutionary theory and game studies can shed light on the forms and psychological functions of horror video games. Horror games invite players to simulate prototypical fear scenarios of uncertainty and danger. These scenarios challenge players to adaptively assess and negotiate their dangers. While horror games thereby instil negative emotion, they also entice players with stimulating challenges of fearful coping. Players who brave these challenges expand their emotional and behavioural repertoire and experience a sense of mastery, explaining the genre’s paradoxical appeal. We end by illustrating our evolutionary approach through an in-depth analysis of Playdead’s puzzle-horror game Limbo. Page 3 of 33 Introduction Imagine this: You are a little boy, lost somewhere deep in the woods at night. You do not know how you got there or how to get out. All you know is that your sister is out there, somewhere, possibly in great danger. You have to find her. The ambiance is alive with animal calls, the flutter of branches and bushes and a welter of noises that you cannot quite make out. -

Bloober Team S.A. 01.01.2017-31.12.2017

BLOOBER TEAM S.A. Sprawozdanie z działalności ZA OKres 01.01.2017-31.12.2017 DATA PUBLIKACJI: 1 CZERWca 2018 Spis treści 1. Wizytówka jednostki 3 2. Zdarzenia, które istotnie wpłynęły na działalność w okresie od 01.01.2017 do 31.12.2017 roku 5 3. Istotne zdarzenia i tendencje po zakończeniu 2017 roku 8 4. Przewidywany rozwój Bloober Team S.A. w 2018 roku 10 5. Czynniki ryzyka i zagrożeń 10 6. Personel i świadczenia socjalne 14 7. Sytuacja majątkowa, finansowa i dochodowa 14 8. Ważniejsze osiągnięcia w dziedzinie badań i rozwoju 15 9. Nabycie akcji własnych 16 10. Posiadane przez jednostkę oddziały (zakłady) 16 11. Instrumenty finansowe i prognozy finansowe 16 12. Zasady ładu korporacyjnego 17 13. Wskaźniki finansowe i niefinansowe 17 SPRAWOZDANIE ZARZĄDU Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI SPÓŁKI 2 ZA OKRES 01.01.2017 R.–31.12.2017 R. Wizytówka jednostki 1. Wizytówka jednostki Bloober Team SA to niezależny producent gier wideo Bloober Team jest reprezentowany na świecie przez specjalizujący się w realizacji projektów z zakre- United Talent Agency - wiodącą hollywodzką agencję su horroru psychologicznego. Członkowie zarządu zajmującą się reprezentowaniem artystów i własności Bloober Team SA – Piotr Babieno i Konrad Rekieć intelektualnych (IP). – należą do grona najbardziej rozpoznawalnych za- rządzających w branży gier wideo na Zachodzie. Mają Bloober Team skupia się na tworzeniu mrocznych thrille- ponad 10-letnie doświadczenie, a na koncie ponad 30 rów i horrorów, skierowanych do wymagającego odbiorcy. zrealizowanych projektów. Zespół Bloober Team składa Tworzy tytuły charakteryzujące się wyrazistymi bohatera- się z blisko 100 osób mających wieloletnie doświad- mi, dojrzałą historią i unikalnym światem. To produkcje, czenie w produkowaniu gier. -

Załacznik 2 Sprawozdanie Z Dzialałności

BLOOBER TEAM S.A. Sprawozdanie z działalności ZA OKres 01.01.2018-31.12.2018 DATA PUBLIKACJI: 31 MAJA 2019 Spis treści 1. Wizytówka jednostki 3 2. Zdarzenia, które istotnie wpłynęły na działalność w okresie od 01.01.2018 do 31.12.2018 roku 5 3. Istotne zdarzenia i tendencje po zakończeniu 2018 roku 9 4. Przewidywany rozwój Bloober Team S.A. w 2018 roku 12 5. Czynniki ryzyka i zagrożeń 12 6. Personel i świadczenia socjalne 16 7. Sytuacja majątkowa, finansowa i dochodowa 16 8. Ważniejsze osiągnięcia w dziedzinie badań i rozwoju 17 9. Nabycie akcji własnych 18 10. Posiadane przez jednostkę oddziały (zakłady) 18 11. Instrumenty finansowe i prognozy finansowe 18 12. Zasady ładu korporacyjnego 19 13. Wskaźniki finansowe i niefinansowe 19 SPRAWOZDANIE ZARZĄDU Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI SPÓŁKI 2 ZA OKRES 01.01.2018 R.–31.12.2018 R. Wizytówka jednostki 1. Wizytówka jednostki Bloober Team SA to niezależny producent gier wideo Bloober Team jest reprezentowany na świecie przez United specjalizujący się w realizacji projektów z zakresu horroru Talent Agency - wiodącą hollywodzką agencję zajmującą się psychologicznego. Członkowie zarządu Bloober Team SA – reprezentowaniem artystów i własności intelektualnych (IP). Piotr Babieno i Konrad Rekieć – należą do grona najbardziej rozpoznawalnych zarządzających w branży gier wideo na Bloober Team skupia się na tworzeniu mrocznych thrille- Zachodzie. Mają ponad 10-letnie doświadczenie, a na koncie rów i horrorów, skierowanych do wymagającego odbiorcy. ponad 30 zrealizowanych projektów. Zespół Bloober Team Tworzy tytuły charakteryzujące się wyrazistymi bohatera- składa się z blisko 100 osób mających wieloletnie doświad- mi, dojrzałą historią i unikalnym światem. To produkcje, czenie w produkowaniu gier. -

Melbourne House at Our Office Books and Software That Melbourne House Has Nearest to You: Published for a Wide Range of Microcomputers

mELBDLIAnE HO LISE PAESEnTS camPLITEA BDDHSB SDFTWAAE Me·lbourne House is an international software publishing company. If you have any difficulties obtaining some Dear Computer User: of our products, please contact I am very pleased to be able to let you know of the Melbourne House at our office books and software that Melbourne House has nearest to you: published for a wide range of microcomputers. United States of America Our aim is to present the best possible books and Melbourne House Software Inc., software for most home computers. Our books 347 Reedwood Drive, present information that is suitable for the beginner Nashville TN 37217 computer user right through to the experienced United Kingdom computer programmer or hobbyist. Melbourne House (Publishers) Ltd., Our software aims to bring out the most possible Glebe Cottage, Glebe House, from each computer. Each program has been written to be a state-of-the-art work. The result has been Station Road, Cheddington, software that has been internationally acclaimed. Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, LU77NA. I would like to hear from you if you have any comments or suggestions about our books and Australia & New Zealand software, or what you would like to see us publish. Melbourne House (Australia) Pty. Ltd., Suite 4, 75 Palmerston Crescent, If you have written something for your computer-a program, an article, or a book-then please send it to South Melbourne, Victoria 3205. us. We will give you a prompt reply as to whether it is a work that we could publish. I trust that you will enjoy our books and software. -

Trigger Happy: Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution

Free your purchased eBook form adhesion DRM*! * DRM = Digtal Rights Management Trigger Happy VIDEOGAMES AND THE ENTERTAINMENT REVOLUTION by Steven Poole Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................ 8 1 RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ......................................10 Our virtual history....................................................10 Pixel generation .......................................................13 Meme machines .......................................................18 The shock of the new ...............................................28 2 THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES ....................................35 Beginnings ...............................................................35 Art types...................................................................45 Happiness is a warm gun .........................................46 In my mind and in my car ........................................51 Might as well jump ..................................................56 Sometimes you kick.................................................61 Heaven in here .........................................................66 Two tribes ................................................................69 Running up that hill .................................................72 It’s a kind of magic ..................................................75 We can work it out...................................................79 Family fortunes ........................................................82 3 UNREAL CITIES ....................................................85 -

How to Download Friday the 13Th Game Ps4 How to Download Friday the 13Th Game Ps4

how to download friday the 13th game ps4 How to download friday the 13th game ps4. PS4 Game Name: Friday the 13th: The Game Working on: CFW 5.05 / PS4 Hen ISO Region: Europe Language: English Game Source: Bluray Game Format: PKG Mirrors Available: Rapidgator. Friday the 13th: The Game (EUR) PS4 ISO Download Links https://filecrypt.cc/Container/9F9A1AA4E9.html. So, what do you think ? You must be logged in to post a comment. Search. About. Welcome to PS4 ISO Net! Our goal is to give you an easy access to complete PS4 Games in PKG format that can be played on your Jailbroken (Currently Firmware 5.05) console. All of our games are hosted on rapidgator.net, so please purchase a premium account on one of our links to get full access to all the games. If you find any broken link, please leave a comment on the respective game page and we will fix it as soon as possible. Friday the 13th: The Game Single Player Mode Will Not Feature a Story. A few months after its debut, Friday the 13th: The Game is close to receiving its single player mode, something that players are looking forward to. However, if players expected a single player mode with proper structure and narrative, Gun Media ended this expectation as they have announced that this mode will have no story. Through a recent update on the official site of Friday the 13th: The Game, Gun Media announced that the single player mode will arrive soon but it will not have any type of actual story or narrative that guides the player within the game. -

Bloober Team S.A. 01.01.2019-31.12.2019

BLOOBER TEAM S.A. Sprawozdanie z działalności grupy kapitałowej za okreS 01.01.2019-31.12.2019 DATA PUBLIKACJI: 5 CZERWCA 2020 Spis treści 1. Informacje ogólne o Spółce Dominującej 3 2. Opis organizacji grupy kapitałowej Bloober Team 5 3. Zdarzenia, które istotnie wpłynęły na działalność oraz wyniki finansowe grupy kapitałowej, jakie nastąpiły w okresie 01.01.2019–31.12.2019 9 4. Istotne zdarzenia i tendencje po zakończeniu 2019 roku 25 5. Przewidywany rozwój grupy kapitałowej 31 6. Czynniki ryzyka i zagrożeń 31 7. Ważniejsze osiągnięcia w dziedzinie badań i rozwoju 33 8. Personel i świadczenia socjalne 34 9. Sytuacja majątkowa, finansowa i dochodowa 35 10. 0Nabycie udziałów (akcji) własnych 35 11. Posiadane przez podmioty wchodzące w skład grupy kapitałowej oddziały (zakłady) 35 12. Stosowanie zasad ładu korporacyjnego 35 13. Instrumenty finansowe 36 14. Wskaźniki finansowe i niefinansowe 37 SPRAWOZDANIE ZARZĄDU Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI GRUPY KAPITAŁOWEJ 2 ZA OKRES 01.01.2019 R.–31.12.2019 R. Informacje ogólne o Spółce Dominującej 1. Informacje ogólne o Spółce Dominującej Firma Bloober Team Spółka Akcyjna Skrót firmy Bloober Team S.A. Siedziba Kraków Adres siedziby ul. Cystersów 9, 31-553 Kraków Telefon + 12 35 38 555 Faks + 12 34 15 842 Adres poczty elektronicznej [email protected], [email protected] Strona internetowa blooberteam.com NIP 676-238-58-17 REGON 120794317 Sąd rejestrowy Sąd Rejonowy dla Krakowa- Śródmieścia w Krakowie, XI Wydział Gospodarczy Krajowego Rejestru Sądowego KRS 0000380757 Kapitał zakładowy Kapitał zakładowy wynosi 176 729,90 zł i dzieli się na: a) 1 020 000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii A, o wartości nominalnej 0,10 zł każda; b) 88 789 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii B, o wartości nominalnej 0,10 zł każda; c) 222 000 akcji zwykłych na okaziciela serii C, o wartości nominalnej 0,10 zł każda. -

From Symbolism to Realism. Physical and Imaginary Video Game Spaces… 195 of Launching Missiles

2019 / Homo Ludens 1(12) From Symbolism to Realism. Physical and Imaginary Video Game Spaces in Historical Aspects Filip Tołkaczewski Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz [email protected] | ORCID: 0000-0002-3310-061X Abstract: Physical and imaginary video game spaces have been constantly evolving, starting from dark indefinable space to ultimately become an incredibly realistic world. This paper aims at illustrating how physical and imaginary spaces have evolved. The older games are, the more indefinable and iconic their physical spaces become. In more modern games physical spaces are being more and more developed. It is now possible to move the place of action from the heights of a symbolic universe to a particular land located in a specific timeline, which made it possible to create realistic settings and characters in a life-like manner. Keywords: two-dimensional, three-dimensional, navigational challenges, game space Homo Ludens 1(12) / 2019 | ISSN 2080-4555 | © Polskie Towarzystwo Badania Gier 2019 DOI: 10.14746/hl.2019.12.10 | received: 31.12.2017 | revision: 18.07.2018 | accepted: 24.11.2019 Game space needs to be understood as more than a series of polygons or pixelated images experienced on a screen. It is something bounded by technology, processed by the hand, eye, and mind, and embodied in the real and imagined identities of players (Salen, Zimmerman, 2006, p. 68). Video games are an extremely varied medium. They can be described using many different parameters. One of them is the space – it can be physical, i.e. such that can be observed on a screen or imaginary that exists in the player’s mind. -

TBBLUE SD Distribution V.0.8B: Latest Distribution Is Always Found At

TBBLUE SD Distribution v.0.8b: Latest distribution is always found at http://www.specnext.com/latestdistro/ Here’s the latest SD image with everything you need to get your Next updated and running! OBLIGATORY DISCLAIMER: READ THIS POST IN ITS ENTIRETY BEFORE ASKING FOR HELP In the links below you will find TBBLUE v.0.8b SD card distribution containing the following changes over version 0.8a: System Software •New Core 1.10.026 with a enhanced Copper (Instruction list updated to 2K), Updated DMA (DMA now implements all DataGear functions). Stabilized NextReg and Z80N extensions. General bugfixes. NOTE: This is the LAST release compatible with Firmware versions 1.04e and 1.04f. Starting with the next version, Multicore support has been added accessible via OUT commands which will require a different Firmware file) •New NextOS 1.97c in two versions: one with Geoff Wearmouth’s Gosh Wonderful 1.33 48K ROM (Default) which is now FULLY compatible with games utilizing the Nirvana/Nirvana+ Engines and one with the standard 48K ROM Also additional fixes in loading of several games which were previously incompatible with even original 128K machines. Changes include improved boot up speed, fixed bugs, code cleanup and extensive use of NextReg and Z80N extended opcodes. This version has also several new commands DEFPROC…ENDPROC, LOCAL and MOD instead of %, DRIVER for installable Interrupt driven drivers (such as the mouse driver), full support for 3 AYs via the PLAY command and has reorganized commands that return values into variables to all use the COMMAND…TO….variable syntax. -

How 1980S Britain Learned to Love the Computer

Lean, Tom. "Computers for the Man in the Street." Electronic Dreams: How 1980s Britain Learned to Love the Computer. London: Bloomsbury Sigma, 2016. 61–88. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472936653.0006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 11:40 UTC. Copyright © Tom Lean 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. CHAPTER THREE Computers for the Man in the Street arly in 1980, adverts began appearing in British newspapers Efor something rather unusual. Sandwiched between pages of economic and social troubles, Thatcherite politics and Cold War paranoia was an advert for a small white box. It looked a little like an overgrown calculator, but declared itself to be the Sinclair ZX80 Personal Computer, and could be bought, ready made, for just £ 99.95. Despite the implausibly low price, the ZX80 was not only a ‘ real computer ’ , but one that cut through computer ‘ mystique ’ to teach programming, and was so easy to use that ‘ inside a day you ’ ll be talking to it like an old friend’ , or so the advert said. It was an impressively crafted piece of marketing, creating an impression of aff ordability and accessibility, ideas hitherto rarely associated with computers. The little white box, and the bold claims that sold it, marked the beginning of a redefi nition of computers as aff ordable and everyday appliances for the masses. At the time microcomputers were broadly split between two basic types.