Threat Simulation in Virtual Limbo Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

MASHRU MISHU CHARACTER ARTIST | | [email protected] | Cell: 347.981.3042

MASHRU MISHU CHARACTER ARTIST | WWW.FX81.COM | [email protected] | Cell: 347.981.3042 PROFILE I love making characters and creatures for video games. I have over a decade of experience and have worked on 30+ game titles. It still feels fresh and interesting to me because I absolutely enjoy making art and learning new techniques and styles every day. I hope to continue making art and contribute to many more projects in the future. SKILLS TOOLS ▪ Realistic human and creature anatomy sculpting ▪ Maya – advanced knowledge 15+ years ▪ Stylized human and creature modeling and sculpting ▪ Photoshop – expert knowledge 20+ years ▪ Hand-painted and photo-realistic texture painting ▪ Mudbox – expert knowledge 15+ years ▪ Realistic costume and cloth sculpting ▪ Topogun ▪ Efficient lowpoly modeling and UV layout ▪ Substance Painter ▪ Strong understanding of materials definition ▪ Zbrush ▪ R&D pipeline and tools improvement ▪ UDK ▪ Optimize art production and scheduling ▪ CryEngine3 ▪ Mentoring and training ▪ Marvelous Designer ▪ Strong communication ▪ 3ds Max EXPERIENCE July-2017 ▪ Senior Character Artist – Cryptic Studios -Present Magic: Legends May-2010 ▪ Freelance Artist - Self Employed Apr-2018 Created characters, creatures, weapons and props for 30+ game titles. (List 2nd page) Jun-2013 ▪ Freelance Artist - Arkane Studios Nov-2014 Character artist on Dishonored 1 & 2 Apr-2013 ▪ Freelance Character Artist - RedLynx Studios Aug-2014 Character artist on Trials: Fusion, Evolution & DLC Jun-2006 ▪ Character Artist - THQ Kaos Studios May-2010 Character -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Please Biofeed the Zombies: Enhancing the Gameplay and Display of a Horror Game Using Biofeedback

Please Biofeed the Zombies: Enhancing the Gameplay and Display of a Horror Game Using Biofeedback Andrew Dekker Erik Champion Interaction Design, School of ITEE, Media Arts, COFA, UNSW, PO Box 259 University of Queensland, Ipswich, Australia Paddington, NSW 2021 Australia [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT commercial computer game, allowing for more dynamic, This paper describes an investigation into how real-time but unpredictable, but also more personalized and situated low-cost biometric information can be interpreted by game experiences. computer games to enhance gameplay without fundamentally changing it. We adapted a cheap sensor, (the The primary benefit of incorporating this technique into Lightstone mediation sensor device by Wild Divine), to computer games is that game developers can offer control record and transfer biometric information about the player over direction of game play and game events to the player. (via sensors that clip over their fingers) into a commercial Rather than the flow and progression within the game being game engine, Half-Life 2. linear and scripted [13], a series of events can be strung together in a sequence that better appeals to the individual. During game play, the computer game was dynamically modified by the player’s biometric information to increase For example, Rouse [12] agrees that allowing the system to the cinematically augmented “horror” affordances. These choose methods of conveying emotion dynamically rather included dynamic changes in the game shaders, screen then forcing players to take specific emotional journeys is a shake, and the creation of new spawning points for the fundamental aspect of enhancing computer games. -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

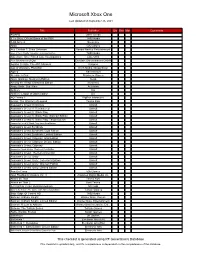

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Bloober Team S.A. 01.01.2017-31.12.2017

BLOOBER TEAM S.A. Sprawozdanie z działalności ZA OKres 01.01.2017-31.12.2017 DATA PUBLIKACJI: 1 CZERWca 2018 Spis treści 1. Wizytówka jednostki 3 2. Zdarzenia, które istotnie wpłynęły na działalność w okresie od 01.01.2017 do 31.12.2017 roku 5 3. Istotne zdarzenia i tendencje po zakończeniu 2017 roku 8 4. Przewidywany rozwój Bloober Team S.A. w 2018 roku 10 5. Czynniki ryzyka i zagrożeń 10 6. Personel i świadczenia socjalne 14 7. Sytuacja majątkowa, finansowa i dochodowa 14 8. Ważniejsze osiągnięcia w dziedzinie badań i rozwoju 15 9. Nabycie akcji własnych 16 10. Posiadane przez jednostkę oddziały (zakłady) 16 11. Instrumenty finansowe i prognozy finansowe 16 12. Zasady ładu korporacyjnego 17 13. Wskaźniki finansowe i niefinansowe 17 SPRAWOZDANIE ZARZĄDU Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI SPÓŁKI 2 ZA OKRES 01.01.2017 R.–31.12.2017 R. Wizytówka jednostki 1. Wizytówka jednostki Bloober Team SA to niezależny producent gier wideo Bloober Team jest reprezentowany na świecie przez specjalizujący się w realizacji projektów z zakre- United Talent Agency - wiodącą hollywodzką agencję su horroru psychologicznego. Członkowie zarządu zajmującą się reprezentowaniem artystów i własności Bloober Team SA – Piotr Babieno i Konrad Rekieć intelektualnych (IP). – należą do grona najbardziej rozpoznawalnych za- rządzających w branży gier wideo na Zachodzie. Mają Bloober Team skupia się na tworzeniu mrocznych thrille- ponad 10-letnie doświadczenie, a na koncie ponad 30 rów i horrorów, skierowanych do wymagającego odbiorcy. zrealizowanych projektów. Zespół Bloober Team składa Tworzy tytuły charakteryzujące się wyrazistymi bohatera- się z blisko 100 osób mających wieloletnie doświad- mi, dojrzałą historią i unikalnym światem. To produkcje, czenie w produkowaniu gier. -

The Unity Glue Principles and Strategies for a Maintainable Unity Project Structure

Zurich University of the Arts Game Design Orientation C The Unity Glue Principles and strategies for a maintainable Unity project structure. Author: Mentors: Goran Saric René Bauer May 22, 2017 Mela Kocher 1 Abstract Today game developers can find hundreds of tutorials on the internet covering specific topics for the popular game engine “Unity”. However, there is a lack of corresponding literature to explain how to integrate all of these different topics together into one big, scalable, and maintainable project. Moreover, Unity’s application program interface was not designed to follow a specific workflow: game developers have the freedom to work in various ways. I personally think this open setting is especially good for fast prototyping production processes, but when it comes to larger projects, where multiple people have to work together productively, the overly flexible engine can easily lead developers to organization problems and bugs. To address this problem, my master’s thesis focuses on project structures within Unity 5.6. In order to first get an overview of existing practices, I interviewed individual developers and game studios. By analysing different methods and approaches for organizing assets and source code, I developed a reliable workflow for my current Unity game “FAR: Lone Sails” [l1]. The results of my research are a “cookbook” that helps to create a maintainable project structure for teams working on a collaborative basis in Unity. 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Thesis structure 5 1.2 Context 6 1.2.1 -

Amnesia the Dark Descent Download Mac Free Full Game

Amnesia the dark descent download mac free full game Continue See more screenshots of Amnesia: Dark Descent, First Man Survival Horror. The game is about immersion, discovery and life through a nightmare. An experience that o should your core. Using a fully physically simulated world, cutting edge 3D graphics and a dynamic sound system, the game pulls no punches when trying to immerse you. Once the game starts, you'll be in control from start to finish. There are no cut scenes or time jumps, no matter what happens, what happens to you first hand. Amnesia: A dark descent throws you head into a dangerous world where danger can lurk around every corner. Your only defenses are hiding, running or using your mind. Other languages Look for similar items by category Of Feedback Open Mac App Store for buying and downloading apps. The last remaining memories disappear into darkness. Your mind is a mess, and only a sense of hunting remains. You have to run away. Woke up... Amnesia: Dark Descent, the first man survival horror. The game is about immersion, discovery and life through a nightmare. An experience that o should your core. Equipment requirements: - Intel processor.- ATI/AMD or NVIDIA graphics card, no other types of hardware are supported. If your computer does not meet the requirements, the game will freeze, crash or not run at all. March 4, 2015 Version 1.3.1 - Fixes various crash problems associated with additional gamepad support in 1.3.- Fixed the ability to re-switch buttons.- Updated launcher to properly limit SSAO samples to 32x. -

Catalogo Nintendo Switch

Inverno 2020/2021 OMAGGIO Che cos'è Nintendo Switch? Nintendo Switch è una console per giocare dove, quando e con chi vuoi La famiglia Nintendo Switch comprende due console Nintendo Switch – pensata per giocare a casa oppure dove vuoi Tre modi di giocare Modalità TV Modalità da tavolo Modalità portatile p.06 ~ p.09 Nintendo Switch Lite pensata per giocare in mobilità p.10 ~ p.11 Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 1 Modalità TV Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Inserisci Nintendo Switch nella base e gioca in HD sulla tua TV. Collegarlo alla TV è facile La console si accende appena la rimuovi Adattatore AC dalla base. Porta la console con te e Nintendo Switch continua a giocare in modalità portatile. Cavo HDMI Basta collegare l'adattatore AC e il cavo HDMI inclusi nella confezione a ogni uscita. Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 2 Usa lo stand integrato e condividi il divertimento Modalità da tavolo con un gioco multiplayer. Inserendo i due Joy-Con nell'impugnatura Joy-Con Joy-Con ottieni un controller tradizionale. Nintendo Switch dispone di Senza l'impugnatura, ogni Joy-Con è un controller due controller, uno per lato, che indipendente. funzionano anche insieme. Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Tre modalità 3 Collega i controller Joy-Con alla console e Modalità portatile gioca dove vuoi. Nintendo Switch Lite – Nintendo Switch Lite è una console compatta, leggera e con comandi integrati. pensata per giocare in mobilità Nintendo Switch Lite è compatibile con tutti i software per Nintendo Switch che possono essere giocati in modalità portatile. -

Załacznik 2 Sprawozdanie Z Dzialałności

BLOOBER TEAM S.A. Sprawozdanie z działalności ZA OKres 01.01.2018-31.12.2018 DATA PUBLIKACJI: 31 MAJA 2019 Spis treści 1. Wizytówka jednostki 3 2. Zdarzenia, które istotnie wpłynęły na działalność w okresie od 01.01.2018 do 31.12.2018 roku 5 3. Istotne zdarzenia i tendencje po zakończeniu 2018 roku 9 4. Przewidywany rozwój Bloober Team S.A. w 2018 roku 12 5. Czynniki ryzyka i zagrożeń 12 6. Personel i świadczenia socjalne 16 7. Sytuacja majątkowa, finansowa i dochodowa 16 8. Ważniejsze osiągnięcia w dziedzinie badań i rozwoju 17 9. Nabycie akcji własnych 18 10. Posiadane przez jednostkę oddziały (zakłady) 18 11. Instrumenty finansowe i prognozy finansowe 18 12. Zasady ładu korporacyjnego 19 13. Wskaźniki finansowe i niefinansowe 19 SPRAWOZDANIE ZARZĄDU Z DZIAŁALNOŚCI SPÓŁKI 2 ZA OKRES 01.01.2018 R.–31.12.2018 R. Wizytówka jednostki 1. Wizytówka jednostki Bloober Team SA to niezależny producent gier wideo Bloober Team jest reprezentowany na świecie przez United specjalizujący się w realizacji projektów z zakresu horroru Talent Agency - wiodącą hollywodzką agencję zajmującą się psychologicznego. Członkowie zarządu Bloober Team SA – reprezentowaniem artystów i własności intelektualnych (IP). Piotr Babieno i Konrad Rekieć – należą do grona najbardziej rozpoznawalnych zarządzających w branży gier wideo na Bloober Team skupia się na tworzeniu mrocznych thrille- Zachodzie. Mają ponad 10-letnie doświadczenie, a na koncie rów i horrorów, skierowanych do wymagającego odbiorcy. ponad 30 zrealizowanych projektów. Zespół Bloober Team Tworzy tytuły charakteryzujące się wyrazistymi bohatera- składa się z blisko 100 osób mających wieloletnie doświad- mi, dojrzałą historią i unikalnym światem. To produkcje, czenie w produkowaniu gier.