How 1980S Britain Learned to Love the Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Newsoft PDF Module

II^Ü ^il II .III*.- •1""" [ v Hintergrundstory Sir Clive Sinclair Sir Clive Miles Sinclair wurde 1940 in London geboren und verließ die Schule im Alter von 17 Jahren, um Redaktionsassistent bei einer Zeitschrift namens "Prac- tical Wireless" {Radiopraxis) zu werden, für die er schon während seiner Schul zeit zu schreiben begonnen hatte. Außerdem schrieb er während der vier Jahre, in denen er bei IPC (International Publishing Company, Verlagshaus der oben genannten Zeitschrift) war, 17 Bücher, hauptsächlich für eine Firma namens Berners. Darunter waren verschiedene Bücher über elektronische Schaltkreise mit Micro-Alloy-Transistoren. 1962 gründete er eine Firma namens Sinclair Radionics. Er verkaufte Tran sistoren, die er von Plesseys gekauft hatte und deren Werte nicht garantiert wur den. Bevor er sie weiterverkaufte, prüfte er sie und teilte sie nach Farben ein. Seine nächste Idee war, einen kleinen Transistor-Verstärker zu entwerfen (2x2x1 cm). Damit sollte man für 1,50 (ca. DM 6,-) eine Verstärkung von 1.000.000 Mal aus den verwendeten Transistoren herausholen können. 127 Als die Firma größer wurde, bezog sie einen neuen Sitz, eine alte Mühle in St. Ives Cambridge. Sie expandierte weiter und produzierte verschiedene Bau 1979 trennte sich Sinclair von Sinclair Radionics und dem NEB, da diese sätze, darunter einen FM-Tuner (damals das kleinste Transistoren-Radio) und ein sich (mit einigen der ersten digitalen Multimetern) auf wissenschaftliche Instru Micro-Fernseh gerat, das aber nie voll zur Produktion gelangte. Er war mehrmals mente spezialisieren wollten, er aber sich mehr für kommerzielle Produkte Erster, einmal mit dem ersten wirklichen Taschenrechner, dem Executive. Der interessierte. Er übernahm die Leitung der Firma Science of Cambridge mit Sitz Umsatz der Firma zu jenem Zeitpunkt ging bereits in die Millionen Pfund. -

Sinclair User Is Published Monthly 29 COMPETITION WINNER We Profile the Winner of Our first Competition

June 1982 The independent magazine for the independent user •••• NOWA • RPM ,. ZX SPECTRUM: CLIVE DOES IT AGAIN We interview Nigel Searle, head of Sinclair's computer division A mother's view of the computer generation Meet the winner of our first competition Eight pages of programs Plus: helpline, mind games, new products, book reviews AMAZE ADVENTURE GAME FOR rifi ZOGS is a brand new game for the 16K ZX81, unlike any other game you've seen on the ZX81. This is without doubt the best game available for this computer, and if you don't believe us, ask somebody who has seen it, or go down to your local computer shop and ask for a demonstration. mAZOGS is a maze adventure game with very fast-moving animated graphics. A large proportion of the program is written in machine code to achieve the most amazing graphics you have ever seen on the Df.81. You will be confronted by a large and complex Maze, which contains somewhere within it a glittering arid fabulous Treasure You not only have the Please se nd int problem of finding the treasure and bringing it out of the maze, you must also face Oty itern Price the guardians of the maze in the form of a force of fearful Mazogs. Even if you survive their attacks you could still starve to death if you get hopelessly lost. B, Fortunately, there are various ways in which you can get help on this dangerous For E10 0 0 inclusive mission. 9 There are three levels of difficulty, and the game comes complete with i e nclose• cne que / P 0 comprehensive instructions. -

Melbourne House at Our Office Books and Software That Melbourne House Has Nearest to You: Published for a Wide Range of Microcomputers

mELBDLIAnE HO LISE PAESEnTS camPLITEA BDDHSB SDFTWAAE Me·lbourne House is an international software publishing company. If you have any difficulties obtaining some Dear Computer User: of our products, please contact I am very pleased to be able to let you know of the Melbourne House at our office books and software that Melbourne House has nearest to you: published for a wide range of microcomputers. United States of America Our aim is to present the best possible books and Melbourne House Software Inc., software for most home computers. Our books 347 Reedwood Drive, present information that is suitable for the beginner Nashville TN 37217 computer user right through to the experienced United Kingdom computer programmer or hobbyist. Melbourne House (Publishers) Ltd., Our software aims to bring out the most possible Glebe Cottage, Glebe House, from each computer. Each program has been written to be a state-of-the-art work. The result has been Station Road, Cheddington, software that has been internationally acclaimed. Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, LU77NA. I would like to hear from you if you have any comments or suggestions about our books and Australia & New Zealand software, or what you would like to see us publish. Melbourne House (Australia) Pty. Ltd., Suite 4, 75 Palmerston Crescent, If you have written something for your computer-a program, an article, or a book-then please send it to South Melbourne, Victoria 3205. us. We will give you a prompt reply as to whether it is a work that we could publish. I trust that you will enjoy our books and software. -

Aboard the Impulse Train: an Analysis of the Two- Channel Title Music Routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B

All aboard the impulse train: an analysis of the two- channel title music routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B. McAlpine This is the author's accepted manuscript. The final publication is available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40869-015-0012-x All Aboard the Impulse Train: An analysis of the two-channel title music routine in Manic Miner Dr Kenneth B. McAlpine University of Abertay Dundee Abstract The ZX Spectrum launched in the UK in April 1982, and almost single- handedly kick-started the British computer games industry. Launched to compete with technologically-superior rivals from Acorn and Commodore, the Spectrum had price and popularity on its side and became a runaway success. One area, however, where the Spectrum betrayed its price-point was its sound hardware, providing just a single channel of 1-bit sound playback, and the first-generation of Spectrum titles did little to challenge the machine’s hardware. Programmers soon realised, however, that with clever machine coding, the Spectrum’s speaker could be encouraged to do more than it was ever designed to. This creativity, borne from constraint, represents a very real example of technology, or rather limited technology, as a driver for creativity, and, since the solutions were not without cost, they imparted a characteristic sound that, in turn, came to define the aesthetic of ZX Spectrum music. At the time, there was little interest in the formal study of either the technologies that support computer games or the social and cultural phenomena that surround them. This retrospective study aims to address that by deconstructing and analysing a key turning point in the musical life of the ZX Spectrum. -

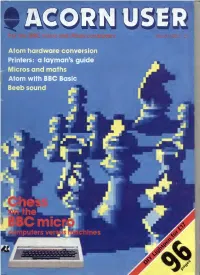

Acorn User March 1983, Number Eight

ii[i: lorn hardware conversion Vinters: a layman's guide Micros and matlis Atom with BBC Basic Beeb sound the C mic ' mputers veri mes T^yT- jS Sb- ^- CONTENTS ACORN USER MARCH 1983, NUMBER EIGHT Editor 3 News 67 Atom analogue converter Tony Quinn 4 Caption competition Circuitry and software by Paul Beverley Editorial Assistant 71 BBC Basic board Milne 8 BBC update Kitty Barry Pickles provides a way round David Allen describes some Managing Editor some of its limitations Jane Fransella spin-offs from the TV series Competition Production 11 Chess: the big review 75 Simon Dally offers software for Peter Ansell John Vaux compares three programs TinaTeare solving his puzzler with a dedicated machine Marketing Manager 15 Beeb forum 79 Book reviews Paul Thompson Assembly language and Pascal Ian Birnbaum on programming Promotion Manager among this month's offerings Pal Bitton 19 Musical synthesis 83 Printers for beginners Publisher Jim McGregor and Alan Watt assess First part of this layman's guide Stanley Malcolm the Beeb's potential by George Hill Designers and Typesetters 27 DIYIightpen GMGraphics, Harrow Hill 89 Back issues and subscriptions Joe Telford shows you how in a Graphic Designer to get the ones you missed, and hardware session of Hints and Tips How Phil Kanssen those you don't want to miss in Great Britain 33 Lightpen OXO Printed 91 Letters by ET.Heron & Co. Ltd Software from Joe Telford Readers' queries and comments on Advertising Agents Lightpen multiple choice 39 everything from discs to EPROMs Computer Marketplace Ltd 41 BBC assembler 20 Orange Street 95 Official dealer list London WC2H 7ED Tony Shaw and John Ferguson Where to go for the upgrades 01-930 1612 addressing tackle indirect and support Distributed to News Trade the 45 Micros in primary schools by Magnum Distribulion Ltd. -

Trigger Happy: Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution

Free your purchased eBook form adhesion DRM*! * DRM = Digtal Rights Management Trigger Happy VIDEOGAMES AND THE ENTERTAINMENT REVOLUTION by Steven Poole Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................ 8 1 RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ......................................10 Our virtual history....................................................10 Pixel generation .......................................................13 Meme machines .......................................................18 The shock of the new ...............................................28 2 THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES ....................................35 Beginnings ...............................................................35 Art types...................................................................45 Happiness is a warm gun .........................................46 In my mind and in my car ........................................51 Might as well jump ..................................................56 Sometimes you kick.................................................61 Heaven in here .........................................................66 Two tribes ................................................................69 Running up that hill .................................................72 It’s a kind of magic ..................................................75 We can work it out...................................................79 Family fortunes ........................................................82 3 UNREAL CITIES ....................................................85 -

CLONE WARS Get a Brazilian

April 2018 Issue 21 PLUS CLONE WARS Get a Brazilian.. Includes material MIND YOUR LANGUAGE not in the video Continued programming show! feature CONTENTS 16. CLONE WARS The Brazilian clones explored. 22. MIND YOUR LANGUAGE 12. OMNI 128HQ Spectrum languages. A new Speccy arrives. FEATURES GAME REVIEWS 4 News from 1987 Knight Lore 6 Find out what was happening back in 1987. Elixir Vitae 8 12 Isometric Games Grand Prix Championship 9 Knightlore and more. Viagem ao Centro da terra 14 16 Clone Wars Exploration of the Brazilian clones. Kung Fu Knights 20 24 Mind Your Language Sewer Rage 21 More languages from George. Dominator 22 32 Play Blackpool Report from the recent event. Spectres 23 36 Vega Games Wanted: Monty Mole 30 Games without instructions on the Vega. 3D Tunnel 31 38 Grumpy Ogre Retro adventuring and championship moaning. Gauntlet 34 42 Omni 128HQ Laptop A new Spectrum arrives. And more…. Page 2 www.thespectrumshow.co.uk EDITORIAL elcome to issue 21 and thank you W I was working on several things at the for taking the time to download and same time on two different comput- read it. ers. I was doing some video editing on As series seven of The Spectrum Show my main PC and at the same time checking emails and researching fu- comes to an end with a mammoth end say, I am impressed with it. It’s a Har- ture features on my little Macbook Air. of series special, the next series is al- lequin (Spectrum modern clone) main ready well underway in the planning Strangely, both required an update, so board fitted inside a new 48K style stages. -

Page 1 of 4 Sinclair ZX80 Computer 1/24/2013

Sinclair ZX80 computer Page 1 of 4 Home Page Old Ads Links Search Buy/Sell! Sinclair ZX80 Anouncedced: February 1980 Available: Late 1980 Price: £99.95 / US$199.95 How many: 50,000 Weight: 12 ounces CPU: Zilog Z80A @ 3.25MHz RAM: 1K, 64K max Display: 22 X 32 text hooks to TV Ports: memory, cassette Peripherals: Sinclair thermal printer OS: ROM BASIC For just $199.95, you can get a complete, powerful, full- function computer, matching or surpassing other personal computers costing several times more. The Sinclair ZX80 is an extraordinary personal computer, compact and briefcase sized, it weighs just 12oz, yet in performance it matches and surpasses systems many times its size and price. The ZX80 is an advanced example of microelectronics design. Inside, it has one-tenth the number of parts of existing comparable machines. In 1980, British company Sinclair released their ZX80 computer for £99.95 (British pound available in the United States, it is considered to be the world's first computer for under U that's what Sinclair Research Ltd stated in all of their ads. At the bottom of the magazine advertisements was an order form: "Please send me __ ZX computer(s) for $199.95 each ..." The ZX-80 was designed with only the base necessit the shelf components - there are no custom or propri involved. An external cassette drive, typical of the era, is the o loading and saving programs. Even cheaper at £75.95 in a kit form, the inexpensive Sinclair ZX-80 introduced many people to the computer world who might otherwise have forth due to the perceived high prices of other albeit more capable computer systems. -

RADIO Electronica 1 September 1973

21e Jaargang RADIO electronica 1 september 1973 ONAFHANKELIJK TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR PRAKTISCHE ELEKTRONICA f 1,70 VERSCHIJNT TWEEMAAL PER MAAND j2september hamsterdam Rai ■ Va-,,:. Si2: ■ \i SU V 7\S 26/9 tm 4/10 rai amsterdam © het instrument 1973I Miniscoop type 211 van Tektronix ___________________________________________________________ ••«*? Amroh componenten ') 4 • * Alp *UM iU 'M AMROH B.V. Telex 15171 Tel. (02942) - 1951* Muiden 17 ONAFHANKELIJK TIJDSCHRIFT VOOR PRAKTISCHE ELEKTRONICA 1 september 1973 waarin opgenomen „ELECTRON DIGEST", orgaan van het Internationaal Documentatie Centrum voor Elektronische Toepassingen 21e Jaargang (IDOCET) Antwerpen Uitgave van: Kluwer Technische Tijdschriften B.V. S Redactie, administratie en advertentie- afdeling Polstraat 9 - Postbus 23 Deventer-6600 - Tel. 0 5700 - 7 55 22 Giro 86 12 21 Bankrelatie: In dit nummer Algemene Bank Nederland N.V., Deventer No. 596247265 Redactie: Telecommunicatietechniek 585 NOS en quadrofonie C. J. Bakker 611 Draadloze ultrasonische afstandbe J. G. Smilde diening voor KTV Medewerkers in Nederland en België: ir. E. A. L. M. Aerts J. H.Jansen W. Arckens drs W. D M Janssen Onderwijs en didactiek 589 Hoger informatica onderwijs en be- R. Bakker H. Jekel W. De Boeck Th. R. J. Koehoorn drijfsinformatica onderwijs ir. W. v. Bokhoven M. Leeuwin 600 44e AES-conventie J. Bron H. Leydens 609 8ste Int. TV-Symposium H. E. Charlouis ing. Th C. Lof (L&S IP) W W. Diefenbach W. Olthoff C. L. Doesburg H Saeys R. Y. Drost drs. F. M. Schimmel Elektroakoestiek 593 Platenspeler met tangentiale arm E. J. R. Engelen mg. J. M. Spekreijse (L&S'IP) 601 Quadrofonie J. H. M. Goddijn F, A. -

From Symbolism to Realism. Physical and Imaginary Video Game Spaces… 195 of Launching Missiles

2019 / Homo Ludens 1(12) From Symbolism to Realism. Physical and Imaginary Video Game Spaces in Historical Aspects Filip Tołkaczewski Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz [email protected] | ORCID: 0000-0002-3310-061X Abstract: Physical and imaginary video game spaces have been constantly evolving, starting from dark indefinable space to ultimately become an incredibly realistic world. This paper aims at illustrating how physical and imaginary spaces have evolved. The older games are, the more indefinable and iconic their physical spaces become. In more modern games physical spaces are being more and more developed. It is now possible to move the place of action from the heights of a symbolic universe to a particular land located in a specific timeline, which made it possible to create realistic settings and characters in a life-like manner. Keywords: two-dimensional, three-dimensional, navigational challenges, game space Homo Ludens 1(12) / 2019 | ISSN 2080-4555 | © Polskie Towarzystwo Badania Gier 2019 DOI: 10.14746/hl.2019.12.10 | received: 31.12.2017 | revision: 18.07.2018 | accepted: 24.11.2019 Game space needs to be understood as more than a series of polygons or pixelated images experienced on a screen. It is something bounded by technology, processed by the hand, eye, and mind, and embodied in the real and imagined identities of players (Salen, Zimmerman, 2006, p. 68). Video games are an extremely varied medium. They can be described using many different parameters. One of them is the space – it can be physical, i.e. such that can be observed on a screen or imaginary that exists in the player’s mind. -

Periodicals for Microcomputers: an Annotated Bibliography Second Edition

Periodicals for Microcomputers: An Annotated Bibliography Second Edition by Thomas C. Stilwell Working Paper No. 21 1985 MSU INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PAPERS Carl K. Eicher, Carl Liedholm, and Michael T. Weber Co-Editors The MSU International Development Paper series is designed to further the comparative analysis of international development activities in Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the Near East. The papers report research findings on historical, as well as contemporary, international development problems. The series includes papers on a wide range of topics, such as alternative rural development strategies; nonfarm employment and small scale industry; housing and construction; farming and marketing systems; food and nutrition policy analysis; economics of rice production in West Africa; technological change, employment, and income distribution; computer techniques for farm and marketing surveys; and farming systems research. The papers are aimed at teachers, researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Spanish, or Arabic. Individuals and institutions in Third World countries may receive single copies free of charge. See inside back cover for a list of available papers and their prices. For more information, write to: MSU International Development Papers Department of Agricultural Economics Agriculture Hall Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1039 U.S.A. PERIODICALS FOR MICROCOMPUTERS: An Annotated Bibliography Second Edition* By Thomas C. Stilwell Visiting Associate Professor Department of Agricultural Economics Michigan State University 1985 *This paper is published by the Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University, under the "Food Security in Africa" Cooperative Agreement DAN-1l90-A-OO-li092-00, U.S.