Translating Research Into Practice: Implications for Serving Families with Young Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five 2015 R U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Office of Head Start Office of Head Start | 8th Floor Portals Building, 1250 Maryland Ave, SW, Washington DC 20024 | eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov Dear Colleagues: The Office of Head Start is proud to provide you with the newly revisedHead Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five. Designed to represent the continuum of learning for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, this Framework replaces the Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Framework for 3–5 Year Olds, issued in 2010. This new Framework is grounded in a comprehensive body of research regarding what young children should know and be able to do during these formative years. Our intent is to assist programs in their efforts to create and impart stimulating and foundational learning experiences for all young children and prepare them to be school ready. New research has increased our understanding of early development and school readiness. We are grateful to many of the nation’s leading early childhood researchers, content experts, and practitioners for their contributions in developing the Framework. In addition, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation and the National Centers of the Office of Head Start, especially the National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning (NCQTL) and the Early Head Start National Resource Center (EHSNRC), offered valuable input. The revised Framework represents the best thinking in the field of early childhood. The first five years of life is a time of wondrous and rapid development and learning.The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five outlines and describes the skills, behaviors, and concepts that programs must foster in all children, including children who are dual language learners (DLLs) and children with disabilities. -

Curriculum Planning and Development Division Post Sea Programme (April 2019 – July 2019) Physical Education

CURRICULUM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DIVISION POST SEA PROGRAMME (APRIL 2019 – JULY 2019) PHYSICAL EDUCATION ! ; : 9 6 : 9 8 7 ! 6 6 ! 1 4 5 , 0 ! 5 4 % , 4 3 2$ ! % $ ! 1 ' # ( /0 ! , . ' , - , + ! * ) ! ' ( ' # & ! % $ # " ! TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE Preamble 3 - 5 SECTION ONE (1) - Warm Up Games 6 - 9 SECTION TWO (2) - Intergenerational Games 10 - 14 Human Musical Chairs/Variation (Hoops) Skipping Los’ my glove on Satr’day Night Moral The Farmer in the Dell Brown Girl/Brown Boy in a ring Hopscotch Rounders Hand Game/Hand Clap SECTION THREE (3) - Teaching Games for Understanding/Game Sense Approach 15 - 30 Netball Basketball Modified Cricket Games/Cricket References ! ! ! PREAMBLE: Physical Education is one of the core subjects on the Trinidad and Tobago National Primary School Curriculum. According to Wuest & Bucher, 2015, “Physical Education is an educational process that has as its aim the improvement of human performance and enhancement of human development through the medium of physical activities”. One of the main goals of this subject is fulfilled through the ability to use knowledge of movement and skills to perform a wide range of physical activities (Wuest & Bucher, 2015). The Physical Education and Sport Unit of the Curriculum Planning and Development Division proposes to use Intergenerational Games and the Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU)/ Games Sense Approach as major aspects of the Post SEA Programme 2018/2019. The TGfU/Games Sense Approach has proven to be very relevant to students at the Post SEA level. Recent studies suggest that, as students progress through the teaching/learning stages, their engagement in the Approach, allows for a smoother transition from one level to another. -

Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education Booklet Developed by Project Coordinator: Dot Brown President, Early Childhood Services, Inc

Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education Booklet Developed By Project Coordinator: Dot Brown President, Early Childhood Services, Inc. Project Consultant: Beverly C. Wright Education Consultant Acknowledgments List of Reviewers Donna Alliston Denise Maxam Division of Child Care & Division of Child Care & Early Early Childhood Education Childhood Education Barbara Gilkey Sandra Reifeiss Arkansas State HIPPY Arkansas Department of Education/Special Education Janie Huddleston Division of Child Care & Kathy Stegall Early Childhood Education Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Education Traci Johnston Arkansas Cooperative Judith Thompson Extension Service Pulaski County Special School District Patty Malone Northwest Arkansas Family Janet Williams Child Care Association Arkansas Baptist State Convention Vicki Mathews Division of Child Care & Debbie Jo Wright Early Childhood Education Northwest Arkansas Family Child Care Association Credits Paige Beebe Gorman Photography Kaplan Early Learning Company Nancy P. Alexander Redwood Preschool Center pages 5, 6, 18 North Little Rock School District photoLitsey Design and Layout pages 9, 13, 15, 19 Massey Design Funding This project is funded by Arkansas Department of Human Services, Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Educa- tion through the Federal Child Care Development Fund. Division of Child Care & Early Childhood Education P.O. Box 1437, Slot S160, Little Rock, AR 72203-1437 Phone: 501-682-9699 • Fax: 501-682-4897 www.state.ar.us/childcare Date 2002 Welcome In this booklet, meet several preschool children through This booklet is words and pictures. Get a glimpse of their families and written for… their home life. View the children in their child care cen- ter, family child care home or preschool classroom. -

Warriors Lose in Overtime

-;n."I'···-r.n.. ···r;:I-'i'-..-·{f-,;--·'~:~"":r7·~~I-,"t'lTr···'~,,~'~.c· ''''''''''''''''''',,!,~ ...... .--.-. - ... ' . r"'" "' ~ ._- -- - ..,. ~-- "'.' ..... - .. -,-- J' .", 99 1 .::.. _~ 1 "{ ',. ~. '.. .I.,. "+ 9 (A )UI HWI;" I .•' ,. /''';' [( .... [ . .. f ", • --, • • ••.• ) oJ rt( H,)Uf?I.. I f;H 1 NG • IJ~::,7 f-. Y ANDLI .. L.. D I~ 1 V ErNC .. # 4* FL.. PAc~() r X 79(;103·- Couple to Warriors run at home celebrate 50th i'; 1~l. 1J See Page 8A See Page 3A {~ 1.1 .1$ ·l•... I .~' . ..' NO. 50 IN OUR 42ND YEAR 35c PER COpy MONDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1987 RutOOSO,. NM 88345 .1-.; ~ . ~ Federal MainStreet program could revamp Midtown area by FRANKIE JARRELL three communities with populations between 3,500 and 50,000 will be ac Ruidoso citizens and businesses will have the opportunity to offer input News Staff Writer cepted next January for MainStreet programs. Community Development op. the proposal at its very outset during Thursday's meeting. Besides lear Block Grant monies will be awarded to those communities for the first year ning what the village can expect if chosen to participate, people at the Take a step back in time and picture Main Street, U.S.A.-not just a of the three-year program. The communities will have the benefit of a con meeting will learn of the commitment expected of MainStreet participants, place but a feeling. tract with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, MainStreet Center, MainStreet towns will be expected to provide the bulk of a minimum Recapturing that feeling of vitality, which made the main streets of so as well as contract services through the Office of the Lieutenant Governor. -

Appendix B Workshop Agendas and Participants

Appendix B Workshop Agendas and Participants First Workshop National Academy of Education (NAEd) Civic Reasoning and Discourse Workshop March 10–11, 2020 March 10, 2020 9:00 am – 10:00 am Breakfast 10:00 am – 10:30 am Welcome, Project Goals, and Best Practices for Virtual Participation Carol D. Lee, Northwestern University Steering Committee Chair 10:30 am – 12:00 pm Panel 1: Philosophical Foundations/Moral Reasoning Panel Chair: Peter Levine, Tufts University Presenter: Sarah M. Stitzlein, University of Cincinnati Discussant: William A. Galston, The Brookings Institution 12:00 pm – 12:45 pm Break 12:45 pm – 2:15 pm Panel 2: History of Education for Democratic Citizenship Panel Chair: Walter C. Parker, University of Washington Presenters: Nancy Beadie, University of Washington Zoë Burkholder, Montclair State University Discussant: Cristina Groeger, Lake Forest College 437 438 EDUCATING FOR CIVIC REASONING AND DISCOURSE 2:30 pm – 4:00 pm Panel 3: Learning Environments and School/Classroom Climate Panel Chair: Judith Torney-Purta, University of Maryland Presenters: Carolyn Barber, University of Missouri-Kansas City Christopher H. Clark, University of North Dakota Discussant: David Campbell, University of Notre Dame 4:15 pm – 5:45 pm Panel 4: Digital Literacy and the Health of Democratic Practice Panel Chair: Joseph Kahne, University of California, Riverside Presenters: Antero Godina Garcia, Stanford University Nicole Mirra, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Discussant: Donna Phillips, District of Columbia Public Schools 5:45 pm Meeting Adjourns for the Day March 11, 2020 9:00 am – 10:00 am Breakfast 10:00 am – 11:30 am Panel 5: Disciplinary Underpinnings and Psychological Foundation Panel Chairs: Carol D. -

Base Running Drills

Base Running Drills 1. Batting Practice Base Running This is the best base running simulated drill work other than actual game base running experience. While your hitters are working on their hitting during batting practice your base runners should be working just as hard on their base running. This is why we call batting practice: YOUR MASCOT Practice. Every facet of the game, other than pitching, should be worked on during this practice session and therefore not just called BP or batting Practice. You should have five players in each group with one player hitting, one player of deck dry swinging and three others with one player at each base. Players at each base should be working on getting primary leads and reads off the bat as the hitter is making contact. The base runners can start on the outfield lip to not interfere with the extra infield ground balls and to not divot up the baselines. The runner on 3rd base should start deep and off the line, to limit the chance of getting hit by a line drive. They react at full speed, but only advance 4-5 steps and then go back to the base. They move up to the next base when the hitter is on his last swing of the round at which time the pitcher yells out “LIVE.” The defense, with one live player at each position, reacts along with the base runners to where the ball is hit. This drill will help condition your base runners to react to balls hit off the bat and limit double play line drives. -

Download the Program Guide

2012 Themed Meeting: Positive Development of Minority Children February 9 – February 11, 2012 Tampa Marriott Waterside Hotel & Marina Tampa, Florida Table of Contents Program Co-Chairs’ Welcome ....................................................................... 2 Meeting Information .................................................................................. 3 Review Panels .......................................................................................... 4 Meeting Session Listing ............................................................................... 5 Thursday .............................................................................................. 5 Plenary Session ................................................................................. 5 Invited Workshop ............................................................................... 6 Invited Panel .................................................................................... 8 Invited Workshop .............................................................................. 12 Welcome Reception ........................................................................... 13 Friday ................................................................................................. 13 Plenary Session ................................................................................ 13 Invited Workshop .............................................................................. 15 Invited Panel .................................................................................. -

MILO In2cricket Skills Program 5 - 6

MILO in2CRICKET introduces girls and boys, in grades 5-6, to Australia’s favourite sport. It’s great fun, kids learn the basic cricket skills and is available for kids of all abilities. MILO in2CRICKET Skills Program 5 - 6 The Australian Way Contents RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT 3 PROGRAM OUTLINE 3 ACTIVITY ESSENTIALS 4 HEALTH & P.E. CURRICULUM OUTCOMES 4 PROGRAM MAP 5 TIPS FOR THE DELIVERER 6 SKILL FOCUS 6 WEEK 1 LOCOMOTION RELAYS 7 GATE BOWLING 8 RAPID FIRE BOWLING 9 KNOCK EM DOWN – BUILD EM UP 10 WEEK 2 4 CORNERS 11 TARGET BATTING 12 SCORING SHOOT OUT 12 BATTING KNOCK-OUT 13 WEEK 3 DERBY CONES (6ERS VS THUNDER) 14 CATCHING 6ERS 15 TAKE WICKETS EVOLUTION 16 SKITTLE THE STUMPS 17 WEEK 4 CAPTAIN’S LOCOMOTION CALL 18 RAPID FIRE BATTING 19 ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES 20 CONTENTS 2 Recommended Equipment for 24 Students EQUIPMENT QUANTITY LARGE BALLS (SCORCHER BALLS) 2 RUBBER CRICKET BALLS 24 ROPES (20M) 2 CONES 24 STUMPS 8 HIGH BOUNCE BALLS 6 BATS 24 MILO IN2CRICKET BAG 1 Program Outline LESSON 1 2 Focus Take Wickets Score Runs Prepare to Perform • Locomotion Relays • 4 Corners Activities • Gate Bowling • Target Batting • Rapid Fire Bowling • Scoring Shoot Out • Knock em down – Build em up • Batting Knock-out Stumps (End of play) Whole Group Discussion Whole Group Discussion LESSON 3 4 Focus Take Wickets Take Wickets & Score Runs Prepare to Perform • Derby Cones • Captain’s Locomotion Call Activities • Catching 6ers • Rapid Fire Batting • Take Wickets Evoluion • Skittle the Stumps Stumps (End of play) Whole Group Discussion Whole Group Discussion RECOMMENDED -

The Panama Canal Review Japanese-Built Locomotive, With

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/panamacanalrevie128pana £ _L His First 30 Days 4 Gray Ladies Go International. 8 New Cristobal Schedules 15 What CARNAVAL Is All About. 10 •ol. 12, No. 8 March 8, 1962 Robert J. Fleming, Jr., Governor-President N. D. Christensen, Press Officer VV*. P. Leber, Lieutenant Governor Joseph Connor, Publications Editor Editorial Assistants: Will Arey Official Panama Canal Ctmpany Publication Eunice Richard and Tobi Bittel Panama Canal Information Officer Published Monthly at Balboa Heights, C. Z. William Burns, Official Photographer Printid at the Printing Plant, Mount Hopc,Canal Zont On sale at all Panama Canal Service Centers, Retail Stores, and the Tivoli Guest House for 10 days after publication date at 5 cents each. Subscriptions, {1 a year; mall and back copies, 10 cents each. Postal money orders made payable to the Panama Canal Company should be mailed to Box M, Balboa Heights, C. Z. Editorial Offices are located in the Administration Buildinc. Balboa Heights, C. Z. $60,000,000 In This Issue Statu* of Major Smprovement* Canal THIS MONTH is Carnival time in Panama and the first few days of March will be devoted to the gay, pie-Lenten festival. The origins of the holiday, its GAILLARD CUT: All widening work on the WIDENING OF legends, and the manner in which it is observed all Empire Reach section of Gaillard Cut will be completed by are described in the article which starts on page 10 December 1962. -

DDA) REMOTE REGULAR MEETING Monday, March 22, 2021 – 3:00 PM (312) 626-6799 | Meeting ID: 872 4802 5598

CITY OF THE VILLAGE OF DOUGLAS DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (DDA) REMOTE REGULAR MEETING Monday, March 22, 2021 – 3:00 PM https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87248025598 (312) 626-6799 | Meeting ID: 872 4802 5598 AGENDA 1. Call toOrder – Remote Special Meeting Procedures 2. Roll Call/Quorum 3. Approval of Agenda - Changes/Additions/Deletions a. Remote Regular Meeting, March 22, 2021 4. Approval of Minutes-Changes/Additions/Deletions a. Remote Regular Meeting, February 22, 2021 5. Officer Reports a. Treasurer (D. Laakso) i. Financial Update – Income Statements: February 28, 2021 ii. Accounts Payable b. Vice Chair (R. Walker) c. Chair (H. Reyes) i. Officer (Secretary) and Board Vacancies ii. Tabled Discussions; 2021 Funding Appeals & DDA Initiatives iii. Written Communications 1. M./M. Balmer, Everyday People Cafe; J. Vickers/S. Kendall, Wild Dog Grille; R. Mayo/K. Bale, Borrowed Time; D. Gregersen/B. Hotz, Alley's All American Diner; J./R. Alexander, The Cove (Re: Social Districts), 03-09-2021 2. B. Burmeister, WMBSC (Re: Douglas Socials), 03-02-2021 3. J. Walvoord, Chamber Music Festival of Saugatuck (Re: Beery Field), 2-17-2021 6. Public Comments (3 minutes, each.) 7. Unfinished Business a. Recap, "Put Your Town on the Map" Pitch Competition 2021 (D. Laakso) b. FY 2021-2022 Budget & TIF Goals Discussion (N. Wikar) - Motion to Consider (Roll Call Vote) 8. New Business a. Social Districts (M. Balmer) - Motion to Recommend (Roll Call Vote) b. Downtown District Zoning; Uses, Performance Standards & Master Plan Integration (N. Wikar) - Motion to Consider (Roll Call Vote) 9. Committee Reports 10. Staff/Manager Reports - Planning & Zoning Administrator (N. -

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

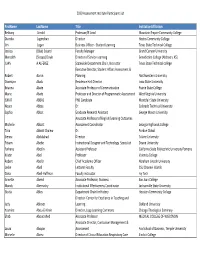

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Students Parliament 6 September 2001 Afternoon Session — Legislative Council Chamber

STUDENTS PARLIAMENT 6 SEPTEMBER 2001 AFTERNOON SESSION — LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL CHAMBER The ACTING PRESIDENT (Hon. A. P. Olexander) took the chair at 12.50 p.m. The ACTING PRESIDENT — Good afternoon. I am Andrew Olexander, a member for Silvan Province, and a member of this chamber. I welcome you all here to the resumption of the Students Parliament and to the Legislative Council. You may have heard earlier in the day that the Legislative Assembly, which is across the corridor and is decorated in green, is the people’s house. While the Legislative Council is elected on a very similar basis to the Legislative Assembly, its role in our democratic process is as a house of review. To achieve that, its members take great care with every piece of legislation that comes to us from the lower house. We analyse it in detail and bring further information and analysis to bear on it. You may have heard quoted what Lord Acton said last century. He said, ‘Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’. That is a very true sentiment, and the whole idea of having a Legislative Council to review the activities of the house of government is so that no chamber has absolute power. The role and traditions of the Legislative Council are very important in our democratic system. Each student here today is represented by three members of Parliament: one is a person from the lower house, and two members represent each and every one of you in this, the upper house. If you do the maths you will see that every upper house electorate has two members and encompasses four lower house seats, so each province is a large electorate.