Shaping Behaviors: Effective Behavior Management Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warriors Lose in Overtime

-;n."I'···-r.n.. ···r;:I-'i'-..-·{f-,;--·'~:~"":r7·~~I-,"t'lTr···'~,,~'~.c· ''''''''''''''''''',,!,~ ...... .--.-. - ... ' . r"'" "' ~ ._- -- - ..,. ~-- "'.' ..... - .. -,-- J' .", 99 1 .::.. _~ 1 "{ ',. ~. '.. .I.,. "+ 9 (A )UI HWI;" I .•' ,. /''';' [( .... [ . .. f ", • --, • • ••.• ) oJ rt( H,)Uf?I.. I f;H 1 NG • IJ~::,7 f-. Y ANDLI .. L.. D I~ 1 V ErNC .. # 4* FL.. PAc~() r X 79(;103·- Couple to Warriors run at home celebrate 50th i'; 1~l. 1J See Page 8A See Page 3A {~ 1.1 .1$ ·l•... I .~' . ..' NO. 50 IN OUR 42ND YEAR 35c PER COpy MONDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1987 RutOOSO,. NM 88345 .1-.; ~ . ~ Federal MainStreet program could revamp Midtown area by FRANKIE JARRELL three communities with populations between 3,500 and 50,000 will be ac Ruidoso citizens and businesses will have the opportunity to offer input News Staff Writer cepted next January for MainStreet programs. Community Development op. the proposal at its very outset during Thursday's meeting. Besides lear Block Grant monies will be awarded to those communities for the first year ning what the village can expect if chosen to participate, people at the Take a step back in time and picture Main Street, U.S.A.-not just a of the three-year program. The communities will have the benefit of a con meeting will learn of the commitment expected of MainStreet participants, place but a feeling. tract with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, MainStreet Center, MainStreet towns will be expected to provide the bulk of a minimum Recapturing that feeling of vitality, which made the main streets of so as well as contract services through the Office of the Lieutenant Governor. -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers. -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

RADARSCREEN Realscreen's Global Pitch Guide

US $7.95 USD Canada $8.95 CDN International $9.95 USUSDD RADARSCREEN realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide A USPS AFSM 100 Approved Polywrap A USPS AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN CANAD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRS.19690.Breakthrough4.inddS.19690.Breakthrough4.indd 1 110/08/110/08/11 22:59:59 PPMM CONTENT SALES INTERNATIONAL THE SENSES MAKING SENSE OF THE WORLD AROUND US 3 x 50 min. | HD, 5.1 and stereo Just one of more than 30 new titles for 2011/2012 FOR MORE DOCUMENTARIES SEE contentsales.ORF.at WILDLIFE, NATURE & SCIENCE, ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN, CULTURE & ART, ENVIRONMENT & GLOBALIZATION, HISTORY & BIOGRAPHIES, LEISURE & LIFESTYLE, SOCIAL ISSUES & RELIGION, PEOPLE & PLACES RRS.19849.ORF.inddS.19849.ORF.indd 1 111/08/111/08/11 111:411:41 AAMM CONTENTS EDITOR’S NOTE . .4 UNITED STATES . .7 CANADA . 27 UNITED KINGDOM . 34 EUROPE . 40 AUSTRALIA . 48 ASIA . 50 INTERNATIONAL . 54 FUNDERS . 60 RADARSCREEN: realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide 3 CContentsEditPub.inddontentsEditPub.indd 3 111/08/111/08/11 22:36:36 PPMM ™ PITCH Realscreen is published 6 times a year by Brunico Communications Ltd., PERFECT 100- 366 Adelaide Street West, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 1R9 Tel. 416-408-2300 Fax 416-408-0870 www.realscreen.com elcome to the second annual edition of VP & Publisher Claire Macdonald [email protected] realscreen’s Global Pitch Guide, designed Editor Barry Walsh [email protected] to give producers and sellers of content the Associate Editor Adam Benzine [email protected] W Staff Writer Kelly Anderson [email protected] intel they need to fi nd the right buyers for their Creative Director Stephen Stanley [email protected] projects, and the information to help them shape Art Director Mark Lacoursiere [email protected] their pitches effectively. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

NYTVF Overall PR 092215 11

PRESS NOTE: Media interested in covering any 2015 New York Television Festival events can apply for credentials by completing this form at NYTVF.com. 11TH ANNUAL NEW YORK TELEVISION FESTIVAL TO FEATURE WGN AMERICA'S MANHATTAN AND A SPECIAL EVENT HOSTED BY NBC DIGITAL ENTERPRISES FEATURING DAN HARMON AS PART OF OPENING NIGHT DOUBLE-HEADER *** Official Artists to have exclusive access to an Industry Welcome Keynote from Joel Stillerman of AMC and SundanceTV and a series of events sponsored by Pivot, including a screening of Please Like Me and Q&A with Josh Thomas, and the NYTVF 2015 Opening Night Party, hosted with Time Warner Cable Free Festival line-up to include Creative Keynote Showrunner Panel; BAFTA, CNN, Pop (Schitt’s Creek) and truTV (Those Who Can’t)-hosted special events; screenings of 50 Official Selections from the Independent Pilot Competition; closing night awards reception and more [NEW YORK, NY, September 22, 2015] – The NYTVF today announced schedule highlights for its eleventh annual New York Television Festival, which begins Monday, October 19 with an opening night screening celebrating season two of WGN America's Manhattan, the critically acclaimed, Emmy Award-winning drama produced by Lionsgate Television, Skydance Television and Tribune Studios. Following a first-look at the episode set to premiere the next night, cast members John Benjamin Hickey, Rachel Brosnahan, Ashley Zukerman, Michael Chernus, Katja Herbers and Mamie Gummer, along with series creator, writer and executive producer Sam Shaw and director and executive producer Thomas Schlamme, have been confirmed to participate in a talk-back panel. Also on opening night will be a special event hosted by NBCUniversal Digital Enterprises, featuring a live performance by Dan Harmon and special guests. -

Insight on Screen Tbivision.Com | August/September 2020

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | August/September 2020 Switched on thinking Delivering diversity Where next for the How kids TV global animation is approaching industry? inclusivity Page 8 Page 14 pOFC TBI AugSep20.indd 1 27/08/2020 18:12 pXX Xilam TBI AugSep20.indd 1 25/08/2020 14:38 Welcome | This issue Contents TBI August/September 2020 8 20 14 24 8. Switched on thinking 20. Talking it out Kids animation companies have adapted rapidly to the e ects of the Spanish-language scripted product is in demand and Latin American global pandemic, but Helen Dugdale expores what lessons have been producers already widely renowed for their fi lm output are fi nding learned and fi nds out where the industry will go next. new opportunities, as Nick Edwards reports. 12. Who’s doing what this fall 24. Kids Hot Picks With the traditional events calendar disrupted, TBI checks in with TBI takes a look at some of the best kids TV o erings making their a variety of distributors to fi nd out how they’re planning to attract way to market, with sneak peeks of Zog And The Flying Doctors, attention online. Green Hornet, The Epic Adventures Of Morph and more. 14. Delivering diversity 30. Launch time Mark Layton takes a deep dive to explore how the global TV Richard Middleton talks to former BBC Studios director of industry is working to improve inclusivity and representation in commissioning & co-production Tobi de Graa about su ering from children’s programming, and asks what needs to happen both in front Covid-19, his agnostic approach to production and why it’s more fun of and behind the camera in order to bring about real change. -

This Year's Emmy Awards Noms Here

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2017 EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS FOR PROGRAMS AIRING JUNE 1, 2016 – MAY 31, 2017 Los Angeles, CA, July 13, 2017– Nominations for the 69th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Hayma Washington along with Anna Chlumsky from the HBO series Veep and Shemar Moore from CBS’ S.W.A.T. "It’s been a record-breaking year for television, continuing its explosive growth,” said Washington. “The Emmy Awards competition experienced a 15 percent increase in submissions for this year’s initial nomination round of online voting. The creativity and excellence in presenting great storytelling and characters across a multitude of ever-expanding entertainment platforms is staggering. “This sweeping array of television shows ranges from familiar favorites like black- ish and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like Westworld, This Is Us and Atlanta. The power of television and its talented performers – in front of and behind the camera – enthrall a worldwide audience. We are thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s seven Drama Series nomInees include five first-timers dIstrIbuted across broadcast,Deadline cable and dIgItal Platforms: Better Call Saul, The Crown, The Handmaid’s Tale, House of Cards, Stranger Things, This Is Us and Westworld. NomInations were also sPread over dIstrIbution Platforms In the OutstandIng Comedy Series category, with newcomer Atlanta joined by the acclaimed black-ish, Master of None, Modern Family, Silicon Valley, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Veep. Saturday Night Live and Westworld led the tally for the most nomInations (22) In all categories, followed by Stranger Things and FEUD: Bette and Joan (18) and Veep (17). -

Impro Theatre's Fairytales Unscripted

IMPRO THEATRE’S FAIRYTALES UNSCRIPTED SAT / FEB 3 / 11:00 AM Directed by Jo McGinley & Kelly Holden Bashar IMPRO THEATRE STAFF Dan O’Connor, producing artistic director Rick Bernstein, managing director Nick Massouh, director of the Impro Theatre School Madi Goff, associate director of the Impro Theatre school Paul Hungerford, Impro Studio producer Matthew Pitner, Impro Studio manager Emily Rose Jacobson, social media coordinator PRODUCTION STAFF Sandra Burns, scenic & costume designer Leigh Allen, lighting designer Alex Caan, technical improviser Jonathan Green, musical director ENSEMBLE Kari Coleman, Lisa Fredrickson, Kelly Holden Bashar, Stephen Kearin, Brian Lohmann, Nick Massouh, Ryan Smith Impro Theatre is supported, in part, by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. Impro Theatre’s programming is made possible, in part, by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs. There will be no intermission. 22 JAN/FEB 2018 ENSEMBLE Kari Coleman Lisa Fredrickson Kelly Holden Bashar Stephen Kearin Brian Lohmann Nick Massouh Ryan Smith WELCOME TO THE SHOW! performing anything that has been previously written or performed. For the uninitiated, this unique form of theatre generates a few questions: What is it like performing a play when you don’t have a script? Who writes these plays? It is terrifying, inspiring, and wonderfully Everyone that is present on stage. exhilarating. The performers are Impro Theatre is an ensemble of actor/ embracing whole-heartedly the acting playwrights who write theatre as they tenet to “be in the moment” as they have perform it. Our crew is improvising the no other choice. -

The Panama Canal Review Japanese-Built Locomotive, With

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/panamacanalrevie128pana £ _L His First 30 Days 4 Gray Ladies Go International. 8 New Cristobal Schedules 15 What CARNAVAL Is All About. 10 •ol. 12, No. 8 March 8, 1962 Robert J. Fleming, Jr., Governor-President N. D. Christensen, Press Officer VV*. P. Leber, Lieutenant Governor Joseph Connor, Publications Editor Editorial Assistants: Will Arey Official Panama Canal Ctmpany Publication Eunice Richard and Tobi Bittel Panama Canal Information Officer Published Monthly at Balboa Heights, C. Z. William Burns, Official Photographer Printid at the Printing Plant, Mount Hopc,Canal Zont On sale at all Panama Canal Service Centers, Retail Stores, and the Tivoli Guest House for 10 days after publication date at 5 cents each. Subscriptions, {1 a year; mall and back copies, 10 cents each. Postal money orders made payable to the Panama Canal Company should be mailed to Box M, Balboa Heights, C. Z. Editorial Offices are located in the Administration Buildinc. Balboa Heights, C. Z. $60,000,000 In This Issue Statu* of Major Smprovement* Canal THIS MONTH is Carnival time in Panama and the first few days of March will be devoted to the gay, pie-Lenten festival. The origins of the holiday, its GAILLARD CUT: All widening work on the WIDENING OF legends, and the manner in which it is observed all Empire Reach section of Gaillard Cut will be completed by are described in the article which starts on page 10 December 1962. -

DDA) REMOTE REGULAR MEETING Monday, March 22, 2021 – 3:00 PM (312) 626-6799 | Meeting ID: 872 4802 5598

CITY OF THE VILLAGE OF DOUGLAS DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (DDA) REMOTE REGULAR MEETING Monday, March 22, 2021 – 3:00 PM https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87248025598 (312) 626-6799 | Meeting ID: 872 4802 5598 AGENDA 1. Call toOrder – Remote Special Meeting Procedures 2. Roll Call/Quorum 3. Approval of Agenda - Changes/Additions/Deletions a. Remote Regular Meeting, March 22, 2021 4. Approval of Minutes-Changes/Additions/Deletions a. Remote Regular Meeting, February 22, 2021 5. Officer Reports a. Treasurer (D. Laakso) i. Financial Update – Income Statements: February 28, 2021 ii. Accounts Payable b. Vice Chair (R. Walker) c. Chair (H. Reyes) i. Officer (Secretary) and Board Vacancies ii. Tabled Discussions; 2021 Funding Appeals & DDA Initiatives iii. Written Communications 1. M./M. Balmer, Everyday People Cafe; J. Vickers/S. Kendall, Wild Dog Grille; R. Mayo/K. Bale, Borrowed Time; D. Gregersen/B. Hotz, Alley's All American Diner; J./R. Alexander, The Cove (Re: Social Districts), 03-09-2021 2. B. Burmeister, WMBSC (Re: Douglas Socials), 03-02-2021 3. J. Walvoord, Chamber Music Festival of Saugatuck (Re: Beery Field), 2-17-2021 6. Public Comments (3 minutes, each.) 7. Unfinished Business a. Recap, "Put Your Town on the Map" Pitch Competition 2021 (D. Laakso) b. FY 2021-2022 Budget & TIF Goals Discussion (N. Wikar) - Motion to Consider (Roll Call Vote) 8. New Business a. Social Districts (M. Balmer) - Motion to Recommend (Roll Call Vote) b. Downtown District Zoning; Uses, Performance Standards & Master Plan Integration (N. Wikar) - Motion to Consider (Roll Call Vote) 9. Committee Reports 10. Staff/Manager Reports - Planning & Zoning Administrator (N. -

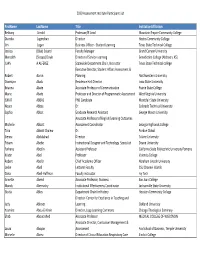

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette