Unprecedented PROJECTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chichen Itza ( /tʃiːˈtʃɛn iːˈtsɑː/;[1] from Yucatec Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza* Maya: Chi'ch'èen Ìitsha',[2] "at the mouth of the well UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Itza") is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site built by the Maya civilization located in the northern center of the Yucatán Peninsula, in the Municipality of Tinúm, Yucatán state, present-day Mexico. Chichen Itza was a major focal point in the northern Maya lowlands from the Late Classic through the Terminal Classic and into the early portion of the Early Postclassic period. The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, from what is called “In the Mexican Origin” and reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico to the Puuc style found among the Country Mexico Puuc Maya of the northern lowlands. The presence of Type Cultural central Mexican styles was once thought to have been Criteria i, ii, iii representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary Reference 483 (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483) interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya Region** Latin America and the Caribbean styles more as the result of cultural diffusion. Inscription history The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the Inscription 1988 (12th Session) site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s Instituto * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list) Institute of Anthropology and History, INAH). The ** Region as classified by UNESCO. -

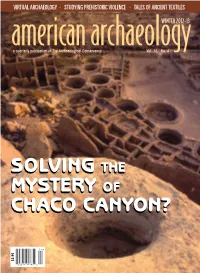

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Original Offering Found at Teotihuacan Pyramid 14 December 2011, by MARK STEVENSON , Associated Press

Original offering found at Teotihuacan pyramid 14 December 2011, By MARK STEVENSON , Associated Press Archaeologists announced Tuesday that they dug remains. to the very core of Mexico's tallest pyramid and found what may be the original ceremonial offering Susan Gillespie, an associate professor of placed on the site of the Pyramid of the Sun before anthropology at the University of Florida who was construction began. not involved in the project, called the find "exciting and important, although I would not say it was The offerings found at the base of the pyramid in unexpected" given that dedicatory offerings were the Teotihuacan ruin site just north of Mexico City commonly placed in MesoAmerican pyramids. include a green serpentine stone mask so delicately carved and detailed that archaeologists "It is exciting that what looks like the original believe it may have been a portrait. foundation dedicatory cache for what was to become the largest (in height) pyramid in Mexico The find also includes 11 ceremonial clay pots (and one of the largest in the world) has finally dedicated to a rain god similar to Tlaloc, who was been found, after much concerted efforts looking for still worshipped in the area 1,500 years later, it," Gillespie wrote in an email. according to a statement by the National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH. She said the find gives a better picture of the continuity of religious practices during The offerings, including bones of an eagle fed Teotihuacan's long history. Some of the same rabbits as well as feline and canine animals that themes found in the offering are repeated in ancient haven't yet been identified, were laid on a sort of murals painted on the city's walls centuries later. -

The Praxis® Study Companion

The Praxis® Study Companion Art: Content Knowledge 5134 www.ets.org/praxis Welcome to the Praxis® Study Companion Welcome to The Praxis®Study Companion Prepare to Show What You Know You have been working to acquire the knowledge and skills you need for your teaching career. Now you are ready to demonstrate your abilities by taking a Praxis® test. Using the Praxis® Study Companion is a smart way to prepare for the test so you can do your best on test day. This guide can help keep you on track and make the most efficient use of your study time. The Study Companion contains practical information and helpful tools, including: • An overview of the Praxis tests • Specific information on the Praxis test you are taking • A template study plan • Study topics • Practice questions and explanations of correct answers • Test-taking tips and strategies • Frequently asked questions • Links to more detailed information So where should you start? Begin by reviewing this guide in its entirety and note those sections that you need to revisit. Then you can create your own personalized study plan and schedule based on your individual needs and how much time you have before test day. Keep in mind that study habits are individual. There are many different ways to successfully prepare for your test. Some people study better on their own, while others prefer a group dynamic. You may have more energy early in the day, but another test taker may concentrate better in the evening. So use this guide to develop the approach that works best for you. -

Paradigms and Syntagms of Ethnobotanical Practice in Pre-Hispanic Northwestern Honduras

Paradigms and Syntagms of Ethnobotanical Practice in Pre-Hispanic Northwestern Honduras By Shanti Morell-Hart A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Rosemary A. Joyce, Chair Professor Christine A. Hastorf Professor Louise P. Fortmann Fall 2011 Abstract Paradigms and Syntagms of Ethnobotanical Practice in Pre-Hispanic Northwestern Honduras by Shanti Morell-Hart Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Rosemary A. Joyce, Chair The relationships between people and plants are complex and highly varied, especially in the mosaic of ecologies represented across Southeastern Mesoamerica. In studying plant use in the past, available technologies and methodologies have expanded and improved, allowing archaeologists to pursue more nuanced approaches to human-plant interactions and complicating previous models based on modern ethnographic accounts and indirect archaeological evidence. In this thesis, I explore various aspects of foodways and ethnobotanical practice in Formative and Classic Northwestern Honduras. My primary data are the actual paleoethnobotanical remains recovered from artifacts and sediments at four sites: Currusté, Cerro Palenque, Puerto Escondido, and Los Naranjos. These remains include microbotanical evidence in the form of starch grains and phytoliths, and macrobotanical evidence including charred seeds and wood. Interweaving practice-based and linguistic-oriented approaches, I structure my work primarily in terms of paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of practice, and how these two axes articulate. I view ethnobotanical practices in terms of possible options available (paradigms) in any given milieu and possible associations (syntagms) between elements. -

Art of the Non-Western World Study Guide

ART OF THE NON- WESTERN WORLD STUDY GUIDE Nancy L. Kelker 1 Contents Introduction: Mastering Art History Chapter 1: Mesoamerica Questions Chapter 2 : Andes Questions Chapter 3: North America Questions Chapter 4: Africa Questions Chapter 5: West Asia Questions Chapter 6: India Questions Chapter 7: Southeast Asia Questions Chapter 8 : China Questions Chapter 9 : Korea and Japan Questions Chapter 10 : Oceanic Questions 2 Introduction : Mastering Art History What does it take to do well in art history classes? A lot of memorizing, right? Actually, doing well in art history requires developing keen observational and analytical skills, not rote memorization. In fact, art history is so good at teaching these skills that many medical schools, including the prestigious Harvard Medical School, are offering art classes to medical students with the aim making them more thoughtful and meticulous observers and ultimately better diagnosticians. So how do you actually develop these good observational skills? The first step is Mindful Looking. Researchers at the J. Paul Getty Museum have found that adult museum- goers spend an average of 30 seconds in front of any work of art1. How much can you glean about a work in half-a-minute? In that time the mind registers a general impression but not much more. Most people hurrying through life (and art museums) aren’t really paying attention and aren’t mindfully looking, which is one of the reasons that studies have shown so-called eye- witnesses to be really bad at correctly identifying suspects. Passively, you saw them but did not observe them. The barrage of media that assaults us 24/7 in the modern digital world exacerbates the problem; the ceaseless flow of inanely superficial infotainment is mind-numbing and the overwhelmed mind tunes out. -

Pyramids in Latin America

Mr. Rarrick World History I VIDEOS http://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/pyramids-in-latin-america The Mayan Encounter 1. What surprised the Spaniards when they reached the Mayans? 2. Whose calendars were more accurate? The Mayans’ or the Europeans’? 3. How does Guerrero help the Mayans and what is ironic about it? The Tomb of King Pacal (Scroll down and it’s on the right side) 4. What is the name of the temple, which is the most complex temple the Mayans have ever tried to build? 5. How would the Mayans communicate within the tomb? 6. What was Pacal’s coffin rich in? 7. The tomb serves as the ______ ________ ______ of Pacal. PYRAMIDS IN LATIN AMERICA Despite the towering reputation of Egypt’s Great Pyramids at Giza, the Americas actually contain more pyramid structures than the rest of the planet combined. Civilizations like the Olmec, Maya, Aztec and Inca all built pyramids to house their deities, as well as to bury their kings. In many of their great city-states, temple-pyramids formed the center of public life and were the site of much holy ritual, including human sacrifice. The best known Latin American pyramids include the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacán in central Mexico, the Castillo at Chichén Itzá in the Yucatan, the Great Pyramid in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the Pyramid at Cholula and the Inca’s great temple at Cuzco in Peru. 8. Did you know that the Americas actually have more pyramids then Egypt? Yes or No 9. -

THE TEMPLE of QUETZALCOATL at TEOTIHUACAN Its Possible Ideological Significance

Ancient Mesoamerica, 2 (1991), 93-105 Copyright © 1991 Cambridge University Press. Printed in the U.S.A. THE TEMPLE OF QUETZALCOATL AT TEOTIHUACAN Its Possible Ideological Significance Alfredo Lopez Austin/ Leonardo Lopez Lujan,b and Saburo Sugiyamac a Institute de Investigaciones Antropologicas, and Facultad de Filosofia y Letras, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico bProyecto Templo Mayor/Subdireccion de Estudios Arqueol6gicos, Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico cDepartment of Anthropology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-2402, USA, and Proyecto Templo de Quetzalc6atl, Teotihuacan, Mexico Abstract In this article the significance of Teotihuacan's most sumptuous monument is studied: the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. Based on iconographic studies, together with the results of recent archaeological excavations, it is possible to deduce that the building was dedicated to the myth of the origin of time and calendric succession. The sculptures on its facades represent the Feathered Serpent at the moment of the creation. The Feathered Serpent bears the complex headdress of Cipactli, symbol of time, on his body. The archaeological materials discovered coincide with iconographic data and with this interpretation. Other monuments in Mesoamerica are also apparently consecrated in honor of this same myth and portray similar symbolism. Sometime about A.D. 150, a pyramid was built at Teotihuacan, Sugiyama 1985, 1989a, 1989b, 1991). A recent study of the characterized by a sculptural splendor that was unsurpassed iconography and the functions of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl during the following centuries of the city's life. The structure led Sugiyama (1989b, 1991) to three central conclusions: (1) the has a rectangular base with seven superimposed tiers (Cabrera sculpture interpreted as the head of the rain god or as the deity and Sugiyama 1982:167) and a stairway on the western facade. -

The Visual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2011 Reclaiming Aztlán: The iV sual Rhetoric of Pre- Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals Kelsey Mahler [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Contemporary Art Commons Recommended Citation Mahler, Kelsey, "Reclaiming Aztlán: The iV sual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals" (2011). Summer Research. Paper 119. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/119 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reclaiming Aztlán: The Visual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals As the Chicano movement took shape in the 1960s, Chicano artists quickly began to articulate the attitudes and goals of the movement in the form of murals that decorated businesses, freeway underpasses, and low-income housing developments. It did not take long for a distinct aesthetic to emerge. Many of the same visual symbols repeatedly appear in these murals, especially those produced during the first two decades of the movement. These included images of historical Mexican or Chicano figures such as Cesar Chavez, Pancho Villa, and Dolores Huerta, cultural icons like the Virgin of Guadalupe, and emblems of political consciousness like the flag of the United Farm Workers. But one of the most important visual themes that emerged was the use of pre-Columbian imagery, which could include images of Aztec or Mayan warriors, gods like Coatlicue or Quetzacoatl, the Aztec calendar stone, depictions of ancient Mesoamerican pyramid architecture, or the Olmec head sculptures found at San Lorenzo and La Venta. -

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. PHOTOGRAPHY: FERNANDO GONZÁLEZ Y GONZÁLEZ AND MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. DRAWINGS: LLUVIA ARRAS, FONDA PORTALES, ANNELYS PÉREZ, RICHARD PERRY AND MARIA RAMOS. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Symbolism TYPES OF ARCHITECTURE General Construction of Pyramid-Temples Temples Types of pyramids Round Pyramids Twin Stair Pyramids Shrines (Adoratorios ) Early Capital Cities City-State Capitals Ballcourts Aqueducts and Dams Markets Gardens BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES THE PRECINCT OF TENOCHTITLAN Introduction Urbanism Ceremonial Plaza (Interior of the Sacred Precinct) The Great Temple Myths Symbolized in the Great Temple Construction Stages Found in the Archaeological Excavations of the Great Temple Construction Phase I Construction Phase II Construction Phase III Construction Phase IV Construction Phase V Construction Phase VI Construction Phase VII Emperor’s Palaces Homes of the Inhabitants Chinampas Ballcourts Temple outside the Sacred Precinct OTHER CITIES Tenayuca The Pyramid Wall of Serpents Tomb-Altar Sta. Cecilia Acatitlan The Pyramid Teopanzolco Tlatelolco The Temple of the Calendar Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl Sacred Well Priests’ Residency The Marketplace Tetzcotzinco Civic Monuments Shrines Huexotla The Wall La Comunidad (The Community) La Estancia (The Hacienda) Santa Maria Group San Marcos Santiago The Ehecatl- Quetzalcoatl Building Tepoztlan The Pyramid-Temple of Tepoztlan Calixtlahuaca Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl The Tlaloc Cluster The Calmecac Group Ballcourt Coatetelco Malinalco Temple I (Cuauhcalli) – Temple of the Eagle and Jaguar Knights Temple II Temple III Temple IV Temple V Temple VI Figures Bibliography INTRODUCTION Aztec architecture reflects the values and civilization of an empire, and studying Aztec architecture is instrumental in understanding the history of the Aztecs, including their migration across Mexico and their re-enactment of religious rituals. -

What Became Authentic P5imitive A5t? Autho5(S)

!"#$%&'(#)'%*+$"',$-(%./-)-$-0'%*/$1 *+$"2/3456%7"'889%://-,;$2, 72+/('6%<+8$+/#8%*,$"/2=282;9>%?28@%A>%B2@%C%3D#9>%EAAF5>%==@%CGEHCCI .+J8-4"'K%J96%&8#(LM'88%.+J8-4"-,;%2,%J'"#8N%2N%$"'%*)'/-(#,%*,$"/2=282;-(#8%*442(-#$-2, 7$#J8'%OPQ6%http://www.jstor.org/stable/656240 *(('44'K6%CFREERCGGA%EG6GE Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cultural Anthropology. http://www.jstor.org What Became Authentic Primitive Art? Shelly Errington University of California, Santa Cruz The category "Primitive Art" was invented at the turn of the 20th century and gained acceptance as "art,"and, with it, monetary value, in the first half of the century-an inspiration to avant-gardeartists, a pleasure to avant-gardecollec- tors.