Pyramids in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

I. a Consideration of Tine and Labor Expenditurein the Constrijction Process at the Teotihuacan Pyramid of the Sun and the Pover

I. A CONSIDERATION OF TINE AND LABOR EXPENDITURE IN THE CONSTRIJCTION PROCESS AT THE TEOTIHUACAN PYRAMID OF THE SUN AND THE POVERTY POINT MOUND Stephen Aaberg and Jay Bonsignore 40 II. A CONSIDERATION OF TIME AND LABOR EXPENDITURE IN THE CONSTRUCTION PROCESS AT THE TEOTIHUACAN PYRAMID OF THE SUN AND THE POVERTY POINT 14)UND Stephen Aaberg and Jay Bonsignore INTRODUCT ION In considering the subject of prehistoric earthmoving and the construction of monuments associated with it, there are many variables for which some sort of control must be achieved before any feasible demographic features related to the labor involved in such construction can be derived. Many of the variables that must be considered can be given support only through certain fundamental assumptions based upon observations of related extant phenomena. Many of these observations are contained in the ethnographic record of aboriginal cultures of the world whose activities and subsistence patterns are more closely related to the prehistoric cultures of a particular area. In other instances, support can be gathered from observations of current manual labor related to earth moving since the prehistoric constructions were accomplished manually by a human labor force. The material herein will present alternative ways of arriving at the represented phenomena. What is inherently important in considering these data is the element of cultural organization involved in such activities. One need only look at sites such as the Valley of the Kings and the great pyramids of Egypt, Teotihuacan, La Venta and Chichen Itza in Mexico, the Cahokia mound group in Illinois, and other such sites to realize that considerable time, effort and organization were required. -

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chichen Itza ( /tʃiːˈtʃɛn iːˈtsɑː/;[1] from Yucatec Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza* Maya: Chi'ch'èen Ìitsha',[2] "at the mouth of the well UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Itza") is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site built by the Maya civilization located in the northern center of the Yucatán Peninsula, in the Municipality of Tinúm, Yucatán state, present-day Mexico. Chichen Itza was a major focal point in the northern Maya lowlands from the Late Classic through the Terminal Classic and into the early portion of the Early Postclassic period. The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, from what is called “In the Mexican Origin” and reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico to the Puuc style found among the Country Mexico Puuc Maya of the northern lowlands. The presence of Type Cultural central Mexican styles was once thought to have been Criteria i, ii, iii representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary Reference 483 (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483) interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya Region** Latin America and the Caribbean styles more as the result of cultural diffusion. Inscription history The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the Inscription 1988 (12th Session) site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s Instituto * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list) Institute of Anthropology and History, INAH). The ** Region as classified by UNESCO. -

Problems in Interpreting the Form and Meaning of Mesoamerican Tomple Platforms

Problems in Interpreting the Form and Meaning of Mesoamerican Tomple Platforms Richard 8. Wright Perhaps the primary fascination of Pre-Columbian art the world is founded and ordered, it acquires meaning. We for art historians lies in the congruence of image and con can then have a sense of place in it. " 2 cept; lacking a widely-used fonn of written language, art In lhe case of the Pyramid of lhe Sun, its western face fonns were employed to express significant concepts, often is parallel to the city's most prominent axis, the avenue to peoples of different languages. popularly known as the Street of the Dead. Tllis axis is Such an extremely logographic role for art should oriented 15°28' east of true nonh for some (as yet) un condition research in a fundamental way. For example, to defined reason (although many other Mesoamcriean sites the extent that Me.wamerican an-fonns literally embody have similar orientations). Offered in explanation arc a concepts, !here can be no real separation of image and variety of hypotheses that often intenningle calendrical, meaning. To interpret such an in the Jjght of Western topographical and celestial elements.' conventions, where meaning can be indirectly perceived (as It should not be surprising to see similar practices in in allegory or the imitation of nature), is to project mislead other Mesoamerican centers, given the religious con• ing expectations which !hen hinder understanding. servatism of ancient cultures in general. Through the One of the most obvious blendings of form and common orientations and orientation techniques of many meaning in Pre-Columbian art is the temple, with its Mesoamerican sites, we can detect specific manifestations supponing platfonn. -

Chalchiuhtlicue)

GODDESS FIGURE (CHALCHIUHTLICUE) This sculpture was carved from volcanic stone about 1,500 years ago in a city named Teotihuacan, located in central Mexico. Like the monumental architecture of Teotihuacan, this three-foot-tall figure is formed of geometric shapes arranged symmetrically. The stone of this sculpture was originally covered with a thin coat of white plaster c. 250-650 Volcanic stone with and then brightly painted. Where can you see traces of red and traces of pigment green pigment? 36 1/4 x 16 1/4 x 16 inches (92.1 x 41.3 x 40.6 cm) Mexican, Central Mexico, The large block at the top of the figure may be a headdress and was Teotihuacan The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, originally painted with colorful designs. The two circular shapes on 1950, 1950-134-282 either side of the face could be earrings or earplugs—decorative rings that are inserted into the earlobe rather than hung from it. FIRST LOOKS The flat, masklike face was once painted red and has two blank, What is the sculpture made of? How do you think it was made? oval eyes and an open mouth shaped like a trapezoid. The figure is Describe the shapes. wearing women’s clothing—a necklace made of rectangular shapes, Which ones are repeated? a fringed blouse called a huipil (wee-PEEL), and a skirt. The large, What colors do you see? strong hands are made of simple, curving shapes, while the wide, flat How is the figure’s face feet are rectangular, like the block on which they stand. -

International Contest

DESIGN OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PROTECTION SYSTEM FOR THE WEST FACADE OF THE PYRAMID OF THE PLUMED SERPENT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF TEOTIHUACAN, STATE OF MEXICO. International Contest DESIGN OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PROTECTION SYSTEM FOR THE WEST FACADE OF THE PYRAMID OF THE PLUMED SERPENT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF TEOTIHUACAN, STATE OF MEXICO 1 DESIGN OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PROTECTION SYSTEM FOR THE WEST FACADE OF THE PYRAMID OF THE PLUMED SERPENT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF TEOTIHUACAN, STATE OF MEXICO INTRODUCTION The ancient city of Teotihuacan was designated by UNESCO as World Heritage in 1988, which is the archeological site of Mexico that, at this moment receives the largest number of visitors, was the seat of the most influential and complex society that had existed in the Americas. It beginning dates from at least the third century Before Common Era. It reached their apogee period between 150 and 600 of Common Era; the city covered more than 23 square kilometers, with an estimated population of approximately 150.000 inhabitants. Teotihuacan expanded its connections to the present states of Jalisco and Zacatecas, also maintained relationship with cities located in Honduras, Belize and Guatemala in Central America. The city was comprised by more than two thousand architectural complexes and it was arranged in neighborhoods creating one of the greatest urban expressions of ancient world. The metropolis has three large architectural complexes: the Pyramid of the Moon, the Pyramid of the Sun and La Ciudadela. The Pyramid of the Plumed Serpent located at this last complex, is one of the most symbolic buildings of Teotihuacan and of all Ancient Mexico. -

Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Mexican and Yukatek Maya Texts

Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Mexican and Yukatek Maya Texts Paul Marcus Worley A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Dr. Rosa Perelmuter Dr. Emilio del Valle Escalante Dr. Gregory Flaxman Dr. David Mora-Marín Dr. Jurgen Buchenau Abstract Paul Worley Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Mexican and Yukatek Maya Texts (Under the director of Rosa Perelmuter) All across Latin America, from the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico to the presidential election of Evo Morales, an Aymara, in Bolivia, indigenous peoples are successfully rearticulating their roles as political actors within their respective states. The reconfiguration of these relationships involves massive social, cultural, and historical projects as well, as indigenous peoples seek to contest stereotypes that have been integral to the region’s popular imagination for over five hundred years. This dissertation examines the image of the indigenous storyteller in contemporary Mexican and Yukatek Maya literatures. Within such a context, Yukatek Maya literature means and must be understood to encompass written and oral texts. The opening chapter provides a theoretical framework for my discussion of the storyteller in Mexican and Yukatek Maya literatures. Chapter 2 undertakes a comparison between the Mexican feminist Laura Esquivel’s novel Malinche and the Yukatek Maya Armando Dzul Ek’s play “How it happened that the people of Maní paid for their sins in the year 1562” to see how each writer employs the figure of the storyteller to rewrite histories of Mexico’s conquest. -

The Magic of Mexico: Pre-Columbian to Contemporary

TRAVEL WITH FRIENDS IN 2014 Mayan pyramid of Kukulcan El Castillo in Chichen-Itza The Magic of Mexico: Pre-Columbian to Contemporary MEXICO CITY TO THE YUCATAN PENINSULA with Chris Carter 14–31 March 2014 (18 days) Tour The Magic of Mexico: leader Pre-Columbian to Contemporary A vibrant palette of ancient cultures and modern art, heritage cities and glorious beaches, colourful music, dance and traditions, Mexico offers a feast for all the senses. Begin with a thorough exploration of the wonderful museums, pre-historic sites, colonial heritage and thriving cultural scene in and around Mexico City. Then travel into the jungle to visit the ancient Mayan sites of Palenque and Yaxchilan, before concluding in the Yucatan Peninsula, famous for its archaeological sites, enchanting colonial cities, beautiful beaches and distinct cuisine. Whilst the itinerary will be comprehensive, there will be time to relax and immerseCANADA yourself in the local culture. Chris Carter Since 1996 Chris Carter has worked full-time as an archaeologist, dividing his time between teaching, commercial archaeology and research in northern Chile. He is currently a PhD scholar at the ANU. Since 1998, Chris has also been involved with the design and At a glance implementation of study tours and has led over 40 tours to • Discover the lives and art of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Toledo Cleveland Central and South America, • Enjoy a full day at the imposing ruins of Teotihuacan Chicago to Spain, Morocco, Ireland and • Marvel at the ancient Mayan cities of Palenque, Yaxchilan, Uxmal and Chichen Itza Turkey, as well as to Vietnam and Cambodia. -

Early Explorers and Scholars

1 Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná http://academic.reed.edu/uxmal/ return to Annotated Bibliography Architecture, Restoration, and Imaging of the Maya Cities of UXMAL, KABAH, SAYIL, AND LABNÁ The Puuc Region, Yucatán, México Charles Rhyne Reed College Annotated Bibliography Early Explorers and Scholars This is not a general bibliography on early explorers and scholars of Mexico. This section includes publications by and about 19th century Euro-American explorers and 19th and early 20th century archaeologists of the Puuc region. Because most early explorers and scholars recorded aspects of the sites in drawings, prints, and photographs, many of the publications listed in this section appear also in the section on Graphic Documentation. A Antochiw, Michel Historia cartográfica de la península de Yucatan. Ed. Comunicación y Ediciones Tlacuilo, S.A. de C.V. Centro Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del I.P.N., 1994. Comprehensive study of maps of the Yucatan from 16th to late 20th centuries. Oversize volume, extensively illustrated, including 6 high quality foldout color maps. The important 1557 Mani map is illustrated and described on pages 35-36, showing that Uxmal was known at the time and was the only location identified with a symbol of an ancient ruin instead of a Christian church. ARTstor Available on the web through ARTstor subscription at: http://www.artstor.org/index.shtml (accessed 2007 Dec. 8) This is one of the two most extensive, publically available collections of early 2 photographs of Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labná, either in print or on the web. The other equally large collection, also on the web, is hosted by the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnography, Harvard Univsrsity (which see). -

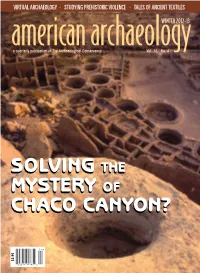

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Architectural Survey at Uxmal Vol. 1

ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY AT UXMAL VOL. 1 George F. Andrews University of Oregon I 2 ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY AT UXMAL 3 ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY AT UXMAL Starting in 1973, I have recorded detailed architectural data on the following groups and structures: r 1) Northwest Quadrangle (North of Northwest Acropolis (1984) a. Structure 4 b. Structure 5 c. Structure 6 d. Structure 7 2) Group 22 (1985) a. Structure 1 b. Structure 3 3) Temple of the Columns (1985) 4) Cemetary Group (1978, 1981) a. Structure 2 5) Nunnery Quadrangle (1973, 1974) a. South Building (+ South Stairway, 1987) b. East Building c. West Building d. North Building c. Venus Temple, lower level, platform of North Building f. East Temple, lower level, platform of North Building g. East and West Rooms, lower level, platform of North Building 6) Northern Long Building(North 6 South Annexes, Nunnery Quadrangle) (1974) a. South Wing b. North Wing 7) Advino Quadxangle(Quadrangle west of Pyramid of the Magician) (1973,1974) a. East Building (Lower West Building, Pyramid of the Magician) b. West Building (House of the Birds) (1993) c. North and South Buildings tKiO 8) Pyramid of the Magician (Pirámide del Advino) (1974, 1981) \f>' a. Temple II . b. Temple 111 c. Temple IV (Chenes Temple) d. Temple V (Upper Temple) 9) Southeast Annex, Nunnery Quadrangle (1974) 4 10) Ballcourt (1978) 11) House of the Turtles (1973) 12) House of tin Governor (1973) r - ''rU ■'■' ?J~**-;" '■> 0 13) Chenes Building 1 (1974) 14) Chenes Building 2 (1978) 15) Group 24(Group northeast of North Quadrangle of South Acropolis(l9B4) a.