Number 81 March 1985 ACCESS to AGRICULTURAL LAND AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 SEAT Report Jwaneng Mine

JWANENG MINE SEAT 3REPORT 2017 - 2020 Contents INTRODUCTION TO JWANENG MINE’S SEAT 14 EXISTING SOCIAL PERFORMANCE 40 1. PROCESS 4. MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES 1.1. Background and Objectives 14 4.1. Debswana’s Approach to Social Performance 41 and Corporate Social Investment 1.2. Approach 15 4.1.1. Approach to Social Performance 41 1.3. Stakeholders Consulted During SEAT 2017 16 4.1.2. Approach to CSI Programmes 41 1.4. Structure of the SEAT Report 19 4.2. Mechanisms to Manage Social Performance 41 2. PROFILE OF JWANENG MINE 20 4.3. Ongoing Stakeholder Engagement towards 46 C2.1. Overview of Debswana’s Operational Context 20 Social Performance Management 2.2. Overview of Jwaneng Mine 22 DELIVERING SOCIO-ECONOMIC BENEFIT 49 2.2.1. Human Resources 23 5. THROUGH ALL MINING ACTIVITIES 2.2.2. Procurement 23 5.1. Overview 50 2.2.3. Safety and Security 24 5.2. Assessment of Four CSI/SED Projects 52 2.2.4. Health 24 5.2.1. The Partnership Between Jwaneng Mine 53 Hospital and Local Government 2.2.5. Education 24 5.2.2. Diamond Dream Academic Awards 54 2.2.6. Environment 25 5.2.3. Lefhoko Diamond Village Housing 55 2.3. Future Capital Investments and Expansion 25 Plans 5.2.4. The Provision of Water to Jwaneng Township 55 and Sese Village 2.3.1. Cut-8 Project 25 5.3. Assessing Jwaneng Mine’s SED and CSI 56 2.3.2. Cut-9 Project 25 Activities 2.3.3. The Jwaneng Resource Extension Project 25 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS 58 (JREP) 6. -

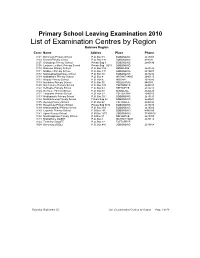

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

A Heritage and Cultural Tourism Destination

MAKING GABORONE A STOP AND NOT A STOP-OVER: A HERITAGE AND CULTURAL TOURISM DESTINATION by Jane Thato Dewah (Student No: 12339556) A Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HERITAGE AND CULTURAL STUDIES) (TOURISM) In the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria SUPERVISOR: Prof. K.L Harris December 2014 DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not been submitted previously at any other university for a degree. ............................................... Signature Jane Thato Dewah ................................................ Date ii Abstract The main objective of the study was to identify cultural heritage sites in and around Gaborone which could serve as tourist attractions. Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana, has been neglected in terms of tourism, although it has all the facilities needed to cater for this market. Very little information with regards to tourist attractions around Gaborone is available and therefore this study set out to identify relevant sites and discussed their history, relevance and potential for tourism. It also considers ways in which these sites can be developed in order to attract tourists. Due to its exclusive concentration on wildlife and the wilderness, tourism in Botswana tends to benefit only a few. Moreover, it is mainly concentrated in the north western region of the country, leaving out other parts of the country in terms of the tourism industry. To achieve the main objective of the study, which is to identify sites around the capital city Gaborone and to evaluate if indeed the sites have got the potential to become tourist attractions, three models have been used. -

Social and Economie Change in a Tswana Village

social and economie change in a tswana village k. f. m. kooi j ma n SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANCE IN A TSWANA VILLAGE Kunnie Kooijman AFRIKA - STUDIECENTRUM LEIDEN 11 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a descriptive study of Bokaa, a village of 1976 inhabitants situated in the Kgatleng district of Botswana. Bokaa was selected for an analysis and description of social and economie change since relatively much is known of the Kgatleng of thirty to forty years ago through the justly famous writings of Isaac Schapera and since the village has had relatively much contact with modernizing influences. It was not intended to present' a static picture of a 'before' and an 'after' but rather to isolate the processes of change which have led to the present social structure. By means of historical records, oral tradition and lifehistories it was possible to analyse the major historical processes which have taken place since 1892, the date the village was founded. The social and economie structure of Bokaa today was studied by means of participant observation, a questionnaire, interviewing, the collection of case-studies and genealogies, and the consultation of the relevant literature. The major conclusions of the study are that the corporate groups of the traditional social structure are breaking down and that the growth of individualism has become a significant feature of the society. In economie activities this is apparent because kinship co-operation has largely diappeared and individuals make their own arrangements with the aim of realising the greatest benefit to themselves. In the kinship realm it is noticeable since the coporate unity of the ward, family- group and lineage segment has weakened considerably and since individuals increasingly seek to manipulate their kinship bonds and duties to their own advantage. -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Final THESIS REPORT-Mareko 2011.Indd

ADAPTING TO SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH ARCHITECTURE: AN INTEGRATED COMMUNITY HUB FOR MOSHUPA VILLAGE, BOTSWANA by Mareko Marcos Gaoboe Submitted in partial fulfi lment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia July 2011 © Copyright by Mareko Marcos Gaoboe, 2011 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a thesis entitled “ADAPTING TO SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH ARCHITECTURE: AN INTEGRATED COMMUNITY HUB FOR MOSHUPA VILLAGE, BOTSWANA” by Mareko Marcos Gaoboe in partial fulfi lment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture. Dated: July 6, 2011 Supervisor: Advisor: External Examiner: ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY Date: July 6, 2011 AUTHOR: Mareko Marcos Gaoboe TITLE: ADAPTING TO SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH ARCHITECTURE: AN INTEGRATED COMMUNITY HUB FOR MOSHUPA VILLAGE, BOTSWANA DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: School of Architecture DEGREE: MArch CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2011 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted ma- terial appearing in the thesis (other than brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledge- ment in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. -

An African Success Story: Botswana1

An African Success Story: Botswana1 Daron Acemoglu2 Simon Johnson3 James A. Robinson4 July 11, 2001 Abstract: Botswana has had the highest rate of per-capita growth of any country in the world in the last 35 years. This occurred despite adverse initial conditions, including minimal investment during the colonial period and high inequality. Botswana achieved this rapid development by following orthodox economic policies. How Botswana sustained these policies is a puzzle because typically in Africa, “good economics” has proved not to be politically feasible. In this paper we suggest that good policies were chosen in Botswana because good institutions, which we refer to as institutions of private property, were in place. Why did institutions of private property arise in Botswana, but not other African nations? We conjecture that the following factors were important. First, Botswana possessed relatively inclusive pre-colonial institutions, placing constraints on political elites. Second, the effect of British colonialism on Botswana was minimal, and did not destroy these institutions. Third, following independence, maintaining and strengthening institutions of private property were in the economic interests of the elite. Fourth, Botswana is very rich in diamonds, which created enough rents that no group wanted to challenge the status quo at the expense of "rocking the boat". Finally, we emphasize that this situation was reinforced by a number of critical decisions made by the post- independence leaders, particularly Presidents Khama and Masire. 1 We are indebted to many people who gave generously of their time and expert knowledge to help us undertake this project. Our greatest debt is to Clark Leith who helped open many doors in Gaborone and who provided many helpful suggestions. -

Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order

CHAPTER 32:02 - TRIBAL LAND: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order Tribal Land (Establishment of Land Tribunals) Order Tribal Land (Subordinate Land Boards) Regulations Tribal Land Regulations ESTABLISHMENT OF SUBORDINATE LAND BOARDS ORDER (under section 19) (15th June, 1973) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPH 1. Citation 2. Establishment 3. Area of jurisdiction 4. Functions Schedule S.I. 47, 1973, S.I. 3, 1979, S.I. 125, 1979, S.I. 132, 1980, S.I. 78, 1981, S.I. 81, 1981, S.I. 110, 1981, S.I. 68, 1982, S.I. 5, 1984, S.I. 92, 1984, S.I. 36, 1986, S.I. 55,1987, S.I. 97, 1989, S.I. 45, 1992, S.I. 66, 1994, S.I. 53, 2002. 1. Citation Copyright Government of Botswana This Order may be cited as the Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order. 2. Establishment The subordinate land boards referred to in the second column of the Schedule hereto are established as the subordinate land boards within the district named in the first column of the said Schedule. 3. Area of jurisdiction The area of jurisdiction in respect of which each subordinate Land Board will perform its functions shall be the area or villages stated in relation to each subordinate land board in the third column of the Schedule. 4. Functions (1) The functions under customary law which vest in the subordinate land authority which are transferred to the subordinate land board shall include the hearing, grant or refusal of applications to use land for— ( a) building residences or extensions thereto; ( b) ploughing to a maximum extent of land determined by the tribal land board; ( c) grazing cattle or other stock; ( d) communal uses in the village. -

List of Schools Visited for Monitoring Visits

LIST OF SCHOOLS VISITED FOR MONITORING VISITS CENTRAL INSPECTORAL AREA LOCATION NAME OF SCHOOL MMADINARE Diloro Diloro MMADINARE Mmadinare Kelele MMADINARE Kgagodi Kgagodi MMADINARE Mmadinare Mmadinare MMADINARE Mmadinare Phethu Mphoeng MMADINARE Robelela Robelela MMADINARE Gojwane Sedibe MMADINARE Serule Serule MMADINARE Mmadinare Tlapalakoma BOTETI Rakops Etsile BOTETI Khumaga Khumaga BOTETI Khwee Khwee BOTETI Mopipi Manthabakwe BOTETI Mmadikola Mmadikola BOTETI Letlhakane Mokane BOTETI Mokoboxane Mokoboxane BOTETI Mokubilo Mokubilo BOTETI Moreomaoto Moreomaoto BOTETI Mosu Mosu BOTETI Motlopi Motlopi BOTETI Letlhakane Retlhatloleng Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boitshoko Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boswelakgomo Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Tebogo BOBIRWA Bobonong Bobonong BOBIRWA Gobojango Gobojango BOBIRWA Bobonong Mabumahibidu BOBIRWA Bobonong Madikwe BOBIRWA Mogapi Mogapi BOBIRWA Molalatau Molalatau BOBIRWA Bobonong Rasetimela BOBIRWA Semolale Semolale BOBIRWA Tsetsebye Tsetsebye 1 | P a g e MAHALAPYE WEST Bonwapitse Bonwapitse MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Leetile MAHALAPYE WEST Mokgenene Mokgenene MAHALAPYE WEST Moralane Moralane MAHALAPYE WEST Mosolotshane Mosolotshane MAHALAPYE WEST Otse Setlhamo MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye St James MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Tshikinyega MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Flowertown MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Mahalapye MHALAPYE EAST Matlhako Matlhako MHALAPYE EAST Mmaphashalala Mmaphashalala MHALAPYE EAST Sefhare Mmutle PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Sekgweng Goo-Sekgweng PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Tau Goo-Tau