25. RECENT ROCK ART STUDIES in PERU Matthias Strecker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quispe Pacco Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL DISTRITO DE NUÑOA TESIS PRESENTADA POR: SANDRO QUISPE PACCO PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN EDUCACIÓN CON MENCIÓN EN LA ESPECIALIDAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES PROMOCIÓN 2016- II PUNO- PERÚ 2017 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SEUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL D ���.r NUÑOA SANDRO QUISPE PACCO APROBADA POR EL SIGUIENTE JURADO: PRESIDENTE e;- • -- PRIMER MIEMBRO --------------------- > '" ... _:J&ª··--·--••__--s;; E • Dr. Jorge Alfredo Ortiz Del Carpio SEGUNDO MIEMBRO --------M--.-S--c--. --R--e-b-�eca Alano�ca G�u�tiérre-z-- -----�--- f DIRECTOR ASESOR ------------------ , M.Sc. Lor-- �VÍlmore Lovón -L-o--v-ó--n-- ------------- Área: Disciplinas Científicas Tema: Patrimonio Histórico Cultural DEDICATORIA Dedico este informe de investigación a Dios, a mi madre por su apoyo incondicional, durante estos años de estudio en el nivel pregrado en la UNA - Puno. Para todos con los que comparto el día a día, a ellos hago la dedicatoria. 2 AGRADECIMIENTO Mi principal agradecimiento a la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano – Puno primera casa superior de estudios de la región de Puno. A la Facultad de Educación, en especial a los docentes de la especialidad de Ciencias Sociales, que han sido parte de nuestro crecimiento personal y profesional. A mi familia por haberme apoyado económica y moralmente en -

El Arte Rupestre Del Antiguo Peru

Jean Guffroy El arte rupestre deI Antiguo Pero Prefacio de Duccio Bonavia 1999 Caratula: Petroglifo antropo-zoomorfo deI sitio de Checta (valle deI Chillon) © Jean Guffroy, 1999 ISBN: 2-7099-1429-8 IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos Contralmirante Montera 141 Casilla 18-1217 Lima 18 - Perd Teléfono: [51 1] 447 60 70 - Fax: 445 76 50 E-Mail: [email protected] IRD Institut de recherche pour le développement Laboratoire ERMES, Technoparc, 5 rue du Carbone, 45072 Orléans Cedex. Este libro corresponde al Tomo 112 de la serie "Travaux de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines" (ISSN 0768-424X) iNDICE PREFACIO por Duccio Bonavia 5 CAPITULO 1: PRESENTACI6N GENERAL 15 - Introoucci6n 15 - Panorama sucinto deI arte rupestre en América deI Sur 16 - El arte rupestre en el territorio peruano 19 CAPITULO II: LAS PINTURAS RUPESTRES DE LA TRADICI6N ANDIN A 23 - La Cueva de Toquepala 26 - Otros sitios de probable tradici6n andina 43 CAPITULO III: LOS ESTILOS NA TURALISTA y SEMINATURALISTA DEL CENTRO 47 - El estilo naturalista de los Andes Centrales 47 - El estilo seminaturalista 51 CAPITULO IV: EL ARTE RUPESTRE PINTADO DU- RANTE LOS ULTIMOS PERIODOS PREHISpANICOS 55 - Las pinturas de estilos Cupinisque y Recuay 55 - El estilo esquematizado y geométrico 59 CAPITULO V: DISTRIBUCIONES ESPACIALES y TEMPORALES DE LAS PIEDRAS GRABADAS 65 - Las ubicaciones geograficas 65 - Fechados y culturas asociadas 71 CAPITULO VI: ORGANIZACI6N y DISTRIBUCI6N DE LAS PIED RAS y FIGURAS GRABADAS 81 3 - Los tipos de agrupaciôn 81 - Distribuciôn de las piedras y figuras grabadas en los sitios mayores 83 - Las estructuras asociadas 88 - Caracterîsticas de las rocas, caras y figuras grabadas 92 CAPITULO VII: ANÂLISIS DE LAS REPRE- SENTACIONES GRABADAS 97 - Las figuras antropomorfas 98 - Felinos, aves rapaces, serpientes 107 - Otros animales 115 - Las figuras geométricas y los signos 118 - Las piedras de tacitas 123 CAPITULO VIII: SINTESIS 133 Agradecimientos: Para mis profesores A. -

The Geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): Classification and Interpretation

PAPERS XXIV Valcamonica Symposium 2011 THE GEOGLYPHS OF HAR KARKOM (NEGEV, ISRAEL): CLASSIFICATION AND INTERPRETATION Federico Mailland* Abstract - The geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): classification and interpretation There is a debate on the possible interpretation of geoglyphs as a form of art, less durable than rock engravings, picture or sculpture. Also, there is a debate on how to date the geoglyphs, though some methods have been proposed. Har Karkom is a rocky mountain, a mesa in the middle of what today is a desert, a holy mountain which was worshipped in the prehis- tory. The flat conformation of the plateau and the fact that it was forbidden to the peoples during several millennia allowed the preservation of several geoglyphs on its flat ground. The geoglyphs of Har Karkom are drawings made on the surface by using pebbles or by cleaning certain areas of stones and other surface rough features. Some of the drawings are over 30 m long. The area of Har Karkom plateau and the southern Wadi Karkom was surveyed and zenithal pictures were taken by means of a balloon with a hanging digital camera. The aerial survey of Har Karkom plateau has reviewed the presence of about 25 geoglyph sites concentrated in a limited area of no more than 4 square km, which is considered to have been a sacred area at the time the geoglyphs were produced and defines one of the major world concentrations of this kind of art. The possible presence among the depictions of large mammals, such as elephant and rhino, already extinct in the area since late Pleistocene, may imply a Palaeolithic dating for some of the pebble drawings, which would make them the oldest pebble drawings known so far. -

World Heritage Patrimoine Mondial 41

World Heritage 41 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, June 2017 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-first session / Quarante-et-unième session Krakow, Poland / Cracovie, Pologne 2-12 July 2017 / 2-12 juillet 2017 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (Peru) (274) Sanctuaire historique de Machu Picchu (Pérou) (274) 22 - 25 February 2017 WHC-ICOMOS-IUCN-ICCROM Reactive Monitoring Mission to “Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu” (Peru) MISSION REPORT 22-25 February 2017 June 2017 Acknowledgements The mission would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Culture of Peru and the authorities and professionals of each institution participating in the presentations, meetings, fieldwork visits and events held during the visit to the property. This mission would also like to express acknowledgement to the following government entities, agencies, departments, divisions and organizations: National authorities Mr. Salvador del Solar Labarthe, Minister of Culture Mr William Fernando León Morales, Vice-Minister of Strategic Development of Natural Resources and representative of the Ministry of Environment Mr. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

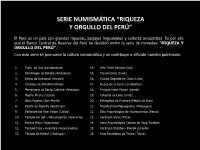

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

Lost Ancient Technology of Peru and Bolivia

Lost Ancient Technology Of Peru And Bolivia Copyright Brien Foerster 2012 All photos in this book as well as text other than that of the author are assumed to be copyright free; obtained from internet free file sharing sites. Dedication To those that came before us and left a legacy in stone that we are trying to comprehend. Although many archaeologists don’t like people outside of their field “digging into the past” so to speak when conventional explanations don’t satisfy, I feel it is essential. If the engineering feats of the Ancient Ones cannot or indeed are not answered satisfactorily, if the age of these stone works don’t include consultation from geologists, and if the oral traditions of those that are supposedly descendants of the master builders are not taken into account, then the full story is not present. One of the best examples of this regards the great Sphinx of Egypt, dated by most Egyptologists at about 4500 years. It took the insight and questioning mind of John Anthony West, veteran student of the history of that great land to invite a geologist to study the weathering patterns of the Sphinx and make an estimate of when and how such degradation took place. In stepped Dr. Robert Schoch, PhD at Boston University, who claimed, and still holds to the theory that such an effect was the result of rain, which could have only occurred prior to the time when the Pharaoh, the presumed builders, had existed. And it has taken the keen observations of an engineer, Christopher Dunn, to look at the Great Pyramid on the Giza Plateau and develop a very potent theory that it was indeed not the tomb of an egotistical Egyptian ruler, as in Khufu, but an electrical power plant that functioned on a grand scale thousands of years before Khufu (also known as Cheops) was born. -

An Exploration of the Impacts of Climate Change on Health and Well Being Among Indigenous Groups in the Andes Region

AN EXPLORATION OF THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON HEALTH AND WELL BEING AMONG INDIGENOUS GROUPS IN THE ANDES REGION By HALIMA TAHIRKHELI Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Leslie Johnson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta June, 2010 2 Table of Content Abstract p.3 Introduction p.4 Andean Native Traditional Way of Life p.9 Environmental Change in the Andean Region p.12 Environmental Stress of Alpine Plants p.23 Impact of Climate Change on Natural Resources p.29 Microfinance p.40 Conclusion p.50 References p.52 List of Figures and Tables Figure 1 Map of Peru p.12 Figure 2 Surface Air Temperature at p.19 tropical Andes between 1939 and 2006 Figure 3 Change in length of ten tropical Andean p.23 glaciers from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia between 1930-2005 Figure 4 Picture of the Queen of the Andes p.25 Table 1 The Diet of Nunoa Quechua Natives p.30 Table 2 Nutritional Value of the Major Peruvian p.32-33 Andean Crops Table 3 Uses of Medicinal Plants from the Callejon p.38 de Huaylas 3 Abstract The Andean areas of Peru, South America are declared to be extremely vulnerable to global warming and these regions are facing major challenges in coping with climate change. One native group from this area, in particular, the Quechua, is the focus of this paper. The Quechua communities include Huanca, Chanka, Q’ero, Taquile, and Amantani, but, for the purposes of my analysis, all of these groups will be dealt with together as they share similar use of natural resources for food and medicine (Wilson, 1999). -

DEPARTAMENTO: DERECHO ADMINISTRATIVO, CONSTITUCIONAL Y CIENCIA POLITICA Tesis Doctoral: “Estrategias Y Medidas De Prevención

ESCUELA DE POSGRADO PROGRAMA DOCTORAL LA GLOBALIZACIÓN A EXAMEN: RETOS Y RESPUESTAS INTERDISCIPLINARES DEPARTAMENTO: DERECHO ADMINISTRATIVO, CONSTITUCIONAL Y CIENCIA POLITICA Tesis Doctoral: “Estrategias y medidas de prevención y planificación ante los problemas ambientales de los cascos, centros o zonas histórico monumentales: Caso del Centro Histórico del Cusco.” Presentado por: Elías Julio Carreño Peralta Director de tesis: Doctor Iñaki Bizente Bárcena Hynojal San Sebastián, 2020 (cc)2020 ELIAS JULIO CARREÑO PERALTA (cc by 4.0) DEDICATORIA: A mi querido padre doctor Guillermo Eusebio Carreño Urquizo y a mi adorada madre María Beatriz Peralta viuda de Carreño, quienes me brindaron la mejor herencia que puede haber y que es el ejemplo de vida, permanente amor y sinceridad que dieron a sus tres hijos, así como la absoluta dedicación a su hogar y plena confianza en Dios, la suprema fuente de vida de todos los seres vivientes que en nuestro hogar encontró un nido muy especial para el desarrollo personal y la fortaleza espiritual, sin los cuáles, no hubiera sido posible mi permanente compromiso con la conservación del patrimonio cultural y natural de la humanidad. 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS: A Dios, Existencia o Imagen Verdadera, Vishnu, Javé o Wiraqocha que permanentemente a través de la historia, ha enviado a nuestro planeta Tierra a sus más amados avatares o mensajeros como Khrisna, Gautama Budha, Jesucristo, Thunupa, Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada y Masaharu Taniguchi, quienes en distintas épocas, continentes, países y contextos culturales vinieron para explicar la importancia de amar primero a Dios sobre todas las cosas y entender que la fuente del equilibrio espiritual, mental y natural viene de su suprema energía y de la pequeña porción de ella que subyace en el corazón de cada ser viviente. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Plan Copesco

GOBIERNO REGIONAL CUSCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO PLAN ESTRATEGICO INSTITUCIONAL 2007 -2011. CUSCO – PERÚ SETIEMBRE 2007 1 GOBIERNO REGIONAL CUSCO PROYECTO ESPECIAL REGIONAL PLAN COPESCO INTRODUCCION En la década de 1960, a solicitud del Gobierno Peruano el PNUD envió misiones para la evaluación de las potencialidades del País en materia de desarrollo sustentable, resultado del cual se priorizó el valor turístico del Eje Cusco Puno para iniciar las acciones de un desarrollo sostenido de inversiones. Sobre la base de los informes Técnicos Vrioni y Rish formulados por la UNESCO y BIRF en los años 1965 y 1968 COPESCO dentro de una perspectiva de desarrollo integral implementa inicialmente sus acciones en la zona del Sur Este Peruano sobre el Eje Machupicchu Cusco Puno Desaguadero. Los años que represente el trabajo regional del Plan COPESCO han permitido el desarrollo de esta actividad. Una de las experiencias constituye el Plan de Desarrollo Turístico de la Región Inka 1995-2005, elaborado por el Plan Copesco por encargo del Gobierno Regional, instrumento de gestión que ha permitido el desarrollo de la actividad turística en la última década, su política también estuvo orientado al desarrollo turístico por circuitos turísticos identificados, El Plan Estratégico Nacional de Turismo- PENTUR 2005-2015, considera que el turismo es la segunda actividad generadora de divisas, y su vez es la actividad prioritaria del Gobierno para el periodo 2005. Este Plan Estratégico se circunscribe en las funciones y lineamientos del MINCETUR, Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Regional Concertado. CUSCO AL 2012, los Planes Estratégicos Provinciales y específicamente en las funciones y objetivos del PER Plan COPESCO, unidad ejecutora del Gobierno Regional Cusco: las que se pueden traducir en la finalidad de ampliar y diversificar la oferta turística en el contexto Regional. -

Session Abstracts

THE INCAS AND THEIR ORIGINS SESSION ABSTRACTS Most sessions focus on a particular region and time period. The session abstracts below serve to set out the issues to be debated in each session. In particular, the abstract aims to outline to each discipline what perspectives and insights the other disciplines can bring to bear on that same topic. A session abstract tends to consist more of questions than answers, then. These are the questions that it would be useful for all participants to be thinking about in advance, so as to be ready to join in the debate on any session. And if you are the speaker giving a synopsis for that session, you may wish to start from the abstract as a guide to how to develop these questions, so as best to provoke the cross-disciplinary debate. DAY 1: TAWANTINSUYU: ITS NATURE AND IMPACTS A1. GENERAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE VARIOUS DISCIPLINES This opening session serves to introduce the various sources of data on the past which together can contribute to a holistic understanding of the Incas and their origins. It serves as the opportunity for each of the various academic disciplines involved to introduce itself briefly to all the others, and for their benefit. The synopses for this session should give just a general outline of the main types of evidence that each discipline uses to come to its conclusions about the Inca past. What is it, within each of their different records of the past, that allows the archaeologist, linguist, ethnohistorian or geneticist to draw inferences as to the nature and strength of Inca control and impacts in different regions? In particular, how can they ‘reconstruct’ resettlements and other population movements within Tawantinsuyu? Also crucial — especially because specialists in other disciplines are not in a position to judge this for themselves — is to clarify how reliable are the main findings and claims that each discipline makes about the Incas. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible.