The Geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): Classification and Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PH 'Wessex White Horses'

Notes from a Preceptor’s Handbook A Preceptor: (OED) 1440 A.D. from Latin praeceptor one who instructs, a teacher, a tutor, a mentor “A horse, a horse and they are all white” Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire Provincial W Bro Michael Lee PAGDC 2017 The White Horses of Wessex Editors note: Whilst not a Masonic topic, I fell Michael Lee’s original work on the mysterious and mystical White Horses of Wiltshire (and the surrounding area) warranted publication, and rightly deserved its place in the Preceptors Handbook. I trust, after reading this short piece, you will wholeheartedly agree. Origins It seems a perfectly fair question to ask just why the Wiltshire Provincial Grand Lodge and Grand Chapter decided to select a white horse rather than say the bustard or cathedral spire or even Stonehenge as the most suitable symbol for the Wiltshire Provincial banner. Most continents, most societies can provide examples of the strange, the mysterious, that have teased and perplexed countless generations. One might include, for example, stone circles, ancient dolmens and burial chambers, ley lines, flying saucers and - today - crop circles. There is however one small area of the world that has been (and continues to be) a natural focal point for all of these examples on an almost extravagant scale. This is the region in the south west of the British Isles known as Wessex. To our list of curiosities we can add yet one more category dating from Neolithic times: those large and mysterious figures dominating our hillsides, carved in the chalk and often stretching in length or height to several hundred feet. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan Website.10

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan 2011-2031 Uffington Parish Council & Baulking Parish Meeting Made Version July 2019 Acknowledgements Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting would like to thank all those who contributed to the creation of this Plan, especially those residents whose bouquets and brickbats have helped the Steering Group formulate the Plan and its policies. In particular the following have made significant contributions: Gillian Butler, Wendy Davies, Hilary Deakin, Ali Haxworth, John-Paul Roche, Neil Wells Funding Groundwork Vale of the White Horse District Council White Horse Show Trust Consultancy Support Bluestone Planning (general SME, Characterisation Study and Health Check) Chameleon (HNA) Lepus (LCS) External Agencies Oxfordshire County Council Vale of the White Horse District Council Natural England Historic England Sport England Uffington Primary School - Chair of Governors P Butt Planning representing Developer - Redcliffe Homes Ltd (Fawler Rd development) P Butt Planning representing Uffington Trading Estate Grassroots Planning representing Developer (Fernham Rd development) R Stewart representing some Uffington land owners Steering Group Members Catherine Aldridge, Ray Avenell, Anna Bendall, Rob Hart (Chairman), Simon Jenkins (Chairman Uffington Parish Council), Fenella Oberman, Mike Oldnall, David Owen-Smith (Chairman Baulking Parish Meeting), Anthony Parsons, Maxine Parsons, Clare Roberts, Tori Russ, Mike Thomas Copyright © Text Uffington Parish Council. Photos © Various Parish residents and Tom Brown’s School Museum. Other images as shown on individual image. Executive Summary This Neighbourhood Plan (the ‘Plan’) was prepared jointly for the Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting. Its key purpose is to define land-use policies for use by the Planning Authority during determination of planning applications and appeals within the designated area. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

High Resolution Drone Surveying of the Pista Geoglyph in Palpa, Peru

geosciences Article High Resolution Drone Surveying of the Pista Geoglyph in Palpa, Peru Karel Pavelka *, Jaroslav Šedina and Eva Matoušková Department of Geomatics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Czech Technical University in Prague, Thakurova 7, Prague 6 16629, Czech Republic; [email protected] (J.Š.); [email protected] (E.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +42-22435-3865 Received: 3 November 2018; Accepted: 10 December 2018; Published: 13 December 2018 Abstract: Currently, satellite images can be used to document historical or archaeological sites in areas that are distant, dangerous, or expensive to visit, and they can be used instead of basic fieldwork in several cases. Nowadays, they have final resolution on 35–50 cm, which can be limited for searching of fine structures. Results using the analysis of very high resolution (VHR) satellite data and super resolution data from drone on an object nearby Palpa, Peru are discussed in this article. This study is a part of Nasca project focused on using satellite data for documentation and the analysis of the famous geoglyphs in Peru near Palpa and Nasca, and partially on the documentation of other historical objects. The use of drone shows advantages of this technology to achieve high resolution object documentation and analysis, which provide new details. The documented site was the “Pista” geoglyph. Discovering of unknown geoglyphs (a bird, a guinea pig, and other small drawings) was quite significant in the area of the well-known geoglyph. The new data shows many other details, unseen from the surface or from the satellite imagery, and provides the basis for updating current knowledge and theories about the use and construction of geoglyphs. -

Kur Geriau? Vaikams Gali Būti Dar Sunkiau, Jeigu Atsi- Dalyvauja 15 Metų Paaugliai

Sek mūsų naujienas Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas SAVAITRAŠTIS TUVI IE ŠK L A S nemokamas L AI KRAŠTIS 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 FREE LITHUANIAN NEWSPAPER www.ekspresas.co.uk Didžioji Britanija Mokykla Lietuvoje LAPĖ apkandžiojo vaiką ar Anglijoje – kur 2 psl. geriau? Interviu 6-7psl. A.Kaniava - apie teatrą, muziką ir gyvenimą 10-11psl. Laisvalaikis Regent street kalėdinių lempučių įžiebimas 12 psl. www.ekspresas.co.uk Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas Kiekvieną savaitę patogiais autobusais bei mikro autobusais vežame keleivius maršrutais Anglija - Lietuva. Siuntinių pervežimas - nuo durų iki durų. LT: +370 60998811 www.lietuva-anglija-vezame.com Lapkričio mėn. bilietai UK: +44 7845 416024 į/iš Londoną (o) TIK £50 El.p.: [email protected] SAVAITRAŠTIS SAVAITRAŠTIS 2 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 3 Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Įėjusi į namus lapė apkandžiojo vaiką Tariama, kad voro įkandimas Dvejų metų ber- riksmą. Mamai nubėgus į vaiko kambarį, niukas buvo išvežtas jie pamatė, kad vaiko koja kruvina, o kam- į ligoninę po to, kai bario kampe blaškosi lapė. lapė įėjusi į namus jį Sykį trenkusi gyvūnui, mama jo nesu- nusinešė moters gyvybę apkandžiojo. gavo ir lapė paspruko atgal pro ten iš kur 60-metė Pat Gough-Irwin (liet. Pet Gou- Pietų Londone, atėjusi. Irvin) po voro įkandimo mirė skausmuose New Addington (liet. Mažamečio tėvai su vaiku išskubėjo į ar- ir agonijoje. Prieš daugiau nei metus pas- Naujasis Adingtonas) timiausią „Croydon University“ ligoninę, klidus žiniai apie nuodingus vorus atsiras- gyvenanti šeima na- kur vaiko kulnas buvo sutvarstytas ir susiū- davo vis daugiau pranešimų apie šių vora- muose augina katiną, tas, bei buvo įduotas antibiotikų kursas. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

Remote Sensing and Geosciences for Archaeology

Books Remote Sensing and Geosciences for Archaeology Edited by Deodato Tapete Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Geosciences www.mdpi.com/journal/geosciences MDPI Remote Sensing and Geosciences for Archaeology Books Special Issue Editor Deodato Tapete MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade MDPI Special Issue Editor Deodato Tapete Italian Space Agency (ASI) Italy Editorial Office MDPI AG St. Alban-Anlage 66 Basel, Switzerland This edition is a reprint of the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Geosciences (ISSN 2076-3263) from 2017–2018 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/geosciences/special_issues/archaeology). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: Books Lastname, F.M.; Lastname, F.M. Article title. Journal Name Year, Article number, page range. First Edition 2018 ISBN 978-3-03842-763-6 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03842-764-3 (PDF) Articles in this volume are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book taken as a whole is © 2018 MDPI, Basel, Switzerland, distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). MDPI Table of Contents About the Special Issue Editor ..................................................................................................................... vii Preface to “Remote Sensing and Geosciences for Archaeology” ........................................................... ix Deodato Tapete Remote Sensing and Geosciences for Archaeology Reprinted from: Geosciences 2018, 8(2), 41; doi: 10.3390/geosciences8020041 ...................................... -

Wiltshire White Horses (Pdf)

Wiltshire’s White Horses The Wiltshire Countryside is famous for its white horse chalk hill figures. It is thought that there have been 13 white horses in existence in Wiltshire, but only 8 are sll visible today. The oldest, largest and perhaps the most well known white horse is carved into the chalk hillside across the border in Oxfordshire. Lile is known of the history of the Uffington White Horse, but it is believed to have influenced the cung of the subsequent Wiltshire horses. The first of the Wiltshire white horses to appear was at Westbury in 878AD, although this figure is no longer visible as a new horse was cut on top in 1778. The most recent horse was cut on the hill above Devizes very near to Team Fredericks to celebrate the Millennium. Westbury: The original Westbury white horse was said to be very different in appearance to the horse that appears today. The earlier horse, if local sketches are to be believed, had short legs and a long heavy body, it wore a saddle and had a tail that pointed upwards. In 1778, Lord Abingdon's steward, a Mr. George Gee took it upon himself to re‐design the Westbury horse and changed the appearance of the landscape for ever more. The old horse was completely lost under this new design, and many branded Gee a Barbarian and vandal. Cherhill: A unique aracon of the Cherhill horse was its eye. Measuring four feet in diameter, Aslop filled the eye with glass boles embedded into the turf face down. -

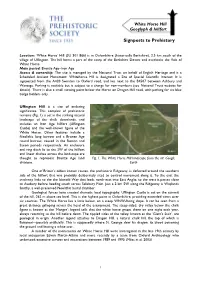

Signposts to Prehistory

White Horse Hill Geoglyph & hillfort Signposts to Prehistory Location: ‘White Horse’ Hill (SU 301 866) is in Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), 2.5 km south of the village of Uffington. The hill forms a part of the scarp of the Berkshire Downs and overlooks the Vale of White Horse. Main period: Bronze Age–Iron Age Access & ownership: The site is managed by the National Trust on behalf of English Heritage and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Whitehorse Hill is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is signposted from the A420 Swindon to Oxford road, and lies next to the B4507 between Ashbury and Wantage. Parking is available but is subject to a charge for non-members (see National Trust website for details). There is also a small viewing point below the Horse on Dragon Hill road, with parking for six blue badge holders only. Uffington Hill is a site of enduring significance. This complex of prehistoric remains (Fig. 1) is set in the striking natural landscape of the chalk downlands, and includes an Iron Age hillfort (Uffington Castle) and the well-known figure of the White Horse. Other features include a Neolithic long barrow and a Bronze Age round barrow, reused in the Roman and Saxon periods respectively. An enclosure and ring ditch lie to the SW of the hillfort and linear ditches across the landscape are thought to represent Bronze Age land Fig. 1. The White Horse Hill landscape from the air. Google divisions. Earth One of Britain’s oldest known routes, the prehistoric Ridgeway, is deflected around the southern side of the hillfort that was probably deliberately sited to control movement along it.