Architectural Sculpture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Surname Research The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Booklets The Cree Family History Society (now Cree Surname Research) was founded in 1991 to encourage research into the history and world-wide distribution of the surname CREE and of families of that name, and to collect, conserve and make available the results of that research. The series Cree Booklets is intended to further those aims by providing a channel through which family histories and related material may be published which might otherwise not see the light of day. Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Oadby, Leicester LE2 5RD England. Cree Surname Research CONTENTS Chart of the descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Crees at the Muskhams - Isaac Cree and Maria Sanders The plight of single parents - the families of Joseph and Sarah Cree The open fields First published in 1994-97 as a series of articles in Cree News by the Cree Family History Society. William Cree and Mary Scott This electronic edition revised and published in 2005 by More accidents - John Cree, Ellen and Thirza Maltsters and iron founders - Francis Cree and Mary King Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Fanny Cree and the boatmen of Newark Oadby Leicester LE2 5RD England © Copyright Mike Spathaky 1994-97, 2005 All Rights Reserved Elizabeth CREE b Collingham, Notts Descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand bap 10 Mar 1850 S Muskham, Notts (three generations) = 1871 Southwell+, Notts Robert -

Introduction to the Monument Groupings

CHAPTER V INTRODUCTION TO THE MONUMENT GROUPINGS The boundaries of individual volumes of the Corpus Nottinghamshire’s ‘main catalogue’ items, albeit in of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture were not drawn to a far smaller data-base. Though they are not un- reflect groupings of monument types; still less were the common elsewhere in the country and the shafts here boundaries of historic English counties. One result of are likely to have required them, there are no single- this has been that — within eastern England anyway stone bases or socket stones identified as plausibly pre- — the groupings to which monuments reported in any Conquest in Nottinghamshire. There is only the very given volume belong sometimes fit within the volume’s impressive composite pyramidal base at Stapleford boundaries, but more often they extend outwards into — an outstanding monument in its own right — adjacent volumes. So it is with Nottinghamshire and which seems to be original to the shaft it still supports Nottinghamshire. With the exception of a tiny group and is associated with it by stone type and simple of local grave-markers, there is no monument type decoration (Stapleford 2, p. 195, Ills. 124, 141–4). whose distribution can be confined to the county. All but one of the Nottinghamshire shafts have lost Rather, the county is placed at the junction of several their cross-heads and strictly it is an assumption that monument groups. Again with the exception of that all were originally topped-off by crosses at all. There tiny group of local grave-markers, relatively little of the is, however, no example that positively suggests that a stone on which early sculpture of Nottinghamshire is decorated Nottinghamshire shaft was without a cross- cut was quarried within the county’s boundaries; most head — i.e. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

7 AUGUST 2018 Application No: 18/00597/FULM Proposal

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 7 AUGUST 2018 Application No: 18/00597/FULM Proposal: Proposed development of 12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows (Re-submission of 16/01885/FULM) Location: Land at Main Street, North Muskham Applicant: Mrs M Wilson Registered: 5 April 2018 Target Date: 5 July 2018 Extension of time agreed in principle The application is being referred to Planning Committee for determination has been referred to Committee by the Business Manager for Growth and Regeneration due to the previous decision of the Planning Committee weighing in the planning balance to be applied in this instance. The Site The site comprises a rectangular shaped area of land of approximately 1.06 hectares which forms the north-east corner of a larger flat field currently used for arable farming. The site is bounded by Main Street to the east and its junction with Glebelands, to the north by a field access and beyond that The Old Hall and to the south and west by open arable fields. Beyond the arable field to the west is the A1. The Old Hall is Grade II listed building and to the north-east of the site is the Grade I listed parish landmark of St Wilfred’s Church. There are various historic buildings along Main Street, particularly close to the church, some of which are identified on the Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record (HER) as Local Interest buildings. The majority of the built form of North Muskham is situated on the eastern side of Main Street, south of Nelson Lane. Whilst there is currently no defined village envelope for the village, the former 1999 Local Plan formerly identified this site as being outside the village envelope that was defined at that time, albeit could be considered to be adjacent to the boundary which ran down the eastern side of Main Street. -

Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council Meeting Held on Monday

DRAFT MINUTES SUBJECT TO RATIFICATION AT 10TH SEPTEMBER MEETING Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council held on Tuesday, 31st July 2018 at 7pm in the Muskham Rural Community Centre Present: Councillor I Harrison, in the Chair Councillor E Catanach Councillor D Jones Councillor P Morris Councillor D Saxton Also in attendance: 9 members of the public NM29-19 Apologies for absence Received and accepted from Cllrs P Beddoe and S Dolby. NM30-19 Declarations of interest It was AGREED that any declarations of interest would be stated by Members as required during the meeting. NM31-19 Minutes The minutes of the meeting held on Monday, 9th July 2018 were accepted as a true and correct record and signed by the Chairman. NM32-19 Public 10 Minute Session The Chair suspended the meeting at 7.01pm to allow members of the public present to raise any questions. No matters were raised and the meeting was reconvened at 7.03pm. NM33-19 Planning (a) 18/00597/FULM – Land at Main Street, North Muskham - Proposed development of 12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows (Re-submission of 16/01885/FULM) Members received and noted the decision notice granting planning permission for the proposed cart shed. The Chair outlined the background to the application being before Members again. It had been submitted in late 2016, revised in September 2017 and then resubmitted in April 2018. The description had changed to ’12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows’ and there were minor alterations with plots 14, 15 and 16 moving approximately 1m further to the south with feature planting beds now sited in front of those units and an increase in the number of new trees planted along the northern and eastern boundaries of the site. -

Planning Supporting Statement

TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK S73 Application to Remove Planning Condition No.7 from Planning Permission 3/15/02039/CMM - The excavation of two stock ponds, construction of a central bank in Bridge Lake through importation of inert materials and associated bank improvement works on Chestnut Lake to improve the habitat and promote sport development in the community and rural area Muskham Lakes, Great North Road, South Muskham, Newark RECEIVED Applicant: Laffey's Ltd NCC 28/12/2016 PLANNING SUPPORTING STATEMENT December 2016 South View, 16 Hounsfield Way, Sutton on Trent, Newark, Nottinghamshire, NG23 6PX Tel: 01636 822528; Mobile 07521 731789; Email: [email protected] Managing Director – Anthony Northcote, HNCert LA(P), Dip TP, PgDip URP, MA, FGS, ICIOB, MInstLM, MCMI, MRTPI TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK is a trading name of Anthony Northcote Planning Ltd, Company Registered in England & Wales (6979909) Website: www.town-planning.co.uk TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK Muskham Lakes, South Muskham This planning statement has been produced by TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK on the basis of the national planning policy and local planning policy position applicable at the date of production. The policy interpretation it concludes are therefore only applicable at the date of production and will potentially vary as time progresses as a consequence of frequent national and local policy changes. It has also been produced to respond to this individual planning proposal and the conclusions it reaches are based only upon the planning application information the LPA has made available on its website, other published information and information provided to the company by the client and/or their representatives. -

THE GABLES FARM LITTLE CARLTON, Nr. NEWARK

inNotti The Newsletter of the Nottinghamshire Building Preservation Trust Limited 14 - 24 REGENT STREET NOTTINGHAM Main Facade Restoration 1986/87 The problems started some years ago but really came to a Administrator and Project Manager employed by each head when part of the eroded main cornice, at Nr. 20 building owner to prepare proposals for the restoration Regent Street, dangerously fell into the forecourt below. As work, obtain costings from appropriate contractors and the premises fo rm part of the W ellington Circus Con supervise the work servation Area, the Planners were contacted regarding the The initial study revealed many weathering problems, possibility of grant aid for the necessary repairs The par ticularly at roof and parapet levels, due to age, neglect, Planners quickly recognised the importance of the poor or inadequate mamtenance. Quotes for a compre buildings and that the problems w ith the fabric of Nr. 20 hensive scheme, including the complete restoration of were common to all six properties in the terrace, built about roofs and chimney stacks, were unacceptable to the 1850 as prestigious houses for emerging businessmen, by building owners because costs were very high. A less the prominent Nottingham Victorian Architect, T. C. Hine. extensive scheme, involving repairs to some stonew ork at A meeting of all owners and tenants of the terrace was set roof level plus the essential rebuilding of the badly eroded up and the idea of a Joint initiative prompted by the City brick parapets and built-up main cornice, together w ith Planning Department, with the prosp ect of possible grant brickwork repairs to the facade and some low-budget assistance from the City Council and English Heritage was improvement works at forecourt level, was finally adopted discussed, with myself fulfilling the role of Architect! and work started. -

1901 Census of Muston

Muston 1901 Census Household Address Name Spouse or Birthdate Birthplace Relationship Occupation Parents M1 Grantham Road Thomas A Shipman Louisa abt 1863 Harley (Harby), Leicestershire, England Head farmer M1 Grantham Road Louisa Shipman Thomas A abt 1864 Stathern, Leicestershire, England Wife M1 Grantham Road Gwendoline Thomas A, Louisa abt 1897 Muston, Leicestershire, England Daughter Shipman M1 Grantham Road Harry C Shipman Thomas A, Louisa abt 1890 Muston, Leicestershire, England Son M1 Grantham Road Marjorie Shipman Thomas A, Louisa abt 1896 Muston, Leicestershire, England Daughter M1 Grantham Road Nina L Shipman Thomas A, Louisa abt 1900 Muston, Leicestershire, England Daughter M1 Grantham Road, Downing L Norman abt 1884 Muston, Leicestershire, England Servant general servant not numbered M1 Grantham Road Josheph Parnham abt 1879 Colston Basset, Nottinghamshire, England Servant groom and cowman M2 Grantham Road Warren H Sayne Emma abt 1849 Marchwood, Hampshire, England Head yardman M2 Grantham Road Emma Sayne Warren H abt 1844 Helpringham, Lincolnshire, England Wife M2 Grantham Road Elizabeth Sayne Warren H, Emma abt 1878 South Muskham, Nottinghamshire Daughter M3 Grantham Road John F Topps Ellen abt 1852 Muston, Leicestershire, England Head agriculatural labourer M3 Grantham Road Ellen Topps John F abt 1852 Allington, Lincolnshire, England Wife M3 Grantham Road Beactrice Topps John F, Ellen abt 1897 Muston, Leicestershire, England Daughter M3 Grantham Road Cisty Topps John F, Ellen abt 1895 Muston, Leicestershire, England Daughter -

Land Adjacent to Railway Line, Off Great North Road, North Muskham, Ng23 6Hn

Report to Planning and Licensing Committee 12 December 2017 Agenda Item: 8 REPORT OF CORPORATE DIRECTOR – PLACE NEWARK AN D SHERWOOD DISTRICT REF. NO.: 17/01644/FULR3N PROPOSAL: USE OF LAND FOR THE IMPORTATION, STORAGE AND PROCESSING OF CONSTRUCTION AND INFRASTRUCTURE INERT WASTE LOCATION: LAND ADJACENT TO RAILWAY LINE, OFF GREAT NORTH ROAD, NORTH MUSKHAM, NG23 6HN APPLICANT: LAFFEY'S LIMITED Purpose of Report 1. To consider a planning application seeking permission for the use of land at Great North Road, North Muskham on which to import, store and process inert wastes, including wastes arising from the Newark Waste and Water Improvement Project. The key issues relate to the principle of this type of development in the countryside having regard to the historic uses of the site; impacts to the amenity of adjacent residential properties from resultant noise; dust; from HGV traffic; and railway safeguarding issues. The recommendation is to approve a temporary planning permission for 2 years linked to the Newark Sewers project. The Site and Surroundings 2. The application site is situated beside the Great North Road and its bridge over the East Coast Railway line, to the south-west of the A1 roundabout at North Muskham, 5km north of Newark on Trent. 3. The site is a small, narrow plot of land of circa 0.28 hectares framed between the railway line to the west and the raised embankment carrying the Great North Road over the railway to the east. (See plan 1) The road then goes onto form the southwestern arm to the roundabout below the A1 flyover. -

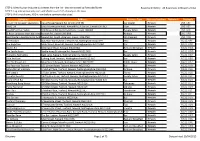

Identify Your Favourite Businesses from the List

STEP 1: Identify your favourite businesses from the list - they are sorted by Postcode/Street Business Directory - All Businesses in Newark v3.xlsx STEP 2: Log into weeconomy.com and check to see if it's already on the map STEP 3: If it's not shown, ADD it now before someone else does! Company Address Business Type Business Location Nationals Postcode Lincoln Volkswagen Specialists Aqua House/Newark Rd, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Car Dealer - Newark LN5 9EJ Vital2 Ltd Lincoln Enterprise Park, Newark Rd, Aubourn, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Gym - Newark LN5 9EJ HeadOffice Hair Salon 310 Newark Rd, North Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 8JX Beauty Salon - Newark LN6 8JX SJ Bean Longcase clock dial restorationNewark and Rd, clock Lincoln repairs LN6 8RB Antique - Newark LN6 8RB Best Western Bentley Hotel And SpaNewark Rd, South Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 9NH Dry Cleaners - Newark LN6 9NH M H Motors Staunton Works/Unit 1 Newark Rd, Nottingham NG13 9PF MOT - Newark NG13 9PF The Angel Inn Main Street, Kneesall, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0AD Bar - Newark NG22 0AD Howes R J Kirklington Road, Newark NG22 0DA Bed and Breakfast - Newark NG22 0DA The Saville Arms Saville Arms/Bilsthorpe Rd, Newark NG22 0DG Bar - Newark NG22 0DG Thoresby Aesthetica Back Lane, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0DJ Beauty Salon - Newark NG22 0DJ Olde Red Lion Eakring Road, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EG Bar - Newark NG22 0EG The Old Plough Inn Main Street, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EZ Public House - Newark NG22 0EZ The Fountain Tuxford 155 Lincoln Road, Tuxford, Newark NG22 0JQ Bar - Newark NG22 0JQ Sally -

Nottinghamshire Minerals Local Plan Representations

Nottinghamshire Minerals Local Plan Representations - by respondent Volume 11 of 11 Respondent number 7873 - 7910 7873 29912 7873 29912 7874 29914 7874 29914 7875 29915 7875 29915 7876 29916 7876 29916 7877 29917 7877 29917 7878 29919 7878 29919 7879 29921 7879 29921 7879 30000 7880 29925-29927 7780 29925 7880 29926 7880 29927 From John Gillespie 27 3 2016 Planning Policy Team, Notts County Council County Hall West Bridgford Nottingham NG2 7QP Nottinghamshire Minerals Local Plan Submission Draft Representation Form Office use only Person No. 7881 Rep No. 29945-29946 Part A - Personal Details Personal details Agent details (where applicable) Title Mr - First Name John - Last name Gillespie - Address line 1 - Address line 2 - Address line 3 - Postcode - Email not available - Organisation not applicable - this is a personal response - Group not applicable - this is a personal response - Wishes for notification The submission of the Minerals Local Plan for independent examination yes please The publication of the recommendations of the inspector yes please The adoption of the Minerals Local Plan yes please I wish to participate at the oral part of the examination, if possible with other commitments. Signature Date 27 March 2016 Name John Gillespie 1 of 23 Office use only Person No. 7881 Rep No. 29945 Part B - Your representation 1. To which part of this document does this representation relate? Policy MP1 Site code - Map/Plan - Paragraph 4.10 - 4.14 Other 2. Do you consider the identified part of the document to be: Legally compliant? Yes No Sound? Yes No √ 3. Do you consider the identified part of the document to be unsound because it is not: (1) Positively √√ (2) Justified? √ (3) Effective ? √ (4) Consistent with prepared? national policy? 4. -

48: Trent and Belvoir Vales Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 48: Trent and Belvoir Vales Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 48: Trent and Belvoir Vales Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform theirdecision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The informationthey contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge.