Introduction to the Monument Groupings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Kesteven - Local Authority In-House Home Improvement Agency

North Kesteven - Local authority in-house home improvement agency Good practice themes 1. Discretionary Assistance within Regulatory Reform Order Policy that supports stay put and move on options in a rural authority area 2. Access to Adult Care Information system to directly update case records and hence ensure statutory agencies are able to determine current status of intervention being provided through housing assistance Context North Kesteven Council (population c 110,000) is one of seven second tier authorities in Lincolnshire and is essentially rural with two small towns and around 100 small communities. Over 80% of the population live in rural areas or market towns. The housing tenure mix is dominated by owner occupation, there is a limited social housing sector (including some council owned stock) and an increasing private rented sector, the latter considered in part to be meeting demand from inward migration to the area due to employment in the agricultural industry. Historically, in common with many second tier authorities across England, available funding for Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) has been modest so until relatively recently there has been an approach where demand for mandatory assistance has been carefully managed. Indeed whilst the Better Care Fund allocation has resulted in a significant increase to the local budget it remains relatively small, £744k in 2018/19. However this level of increase has since 2016 enabled the introduction of several forms of discretionary assistance for disabled older people in a way that better meets the ambition of the local authority to directly provide or enable improvements in health and wellbeing of residents. -

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Surname Research The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Booklets The Cree Family History Society (now Cree Surname Research) was founded in 1991 to encourage research into the history and world-wide distribution of the surname CREE and of families of that name, and to collect, conserve and make available the results of that research. The series Cree Booklets is intended to further those aims by providing a channel through which family histories and related material may be published which might otherwise not see the light of day. Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Oadby, Leicester LE2 5RD England. Cree Surname Research CONTENTS Chart of the descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Crees at the Muskhams - Isaac Cree and Maria Sanders The plight of single parents - the families of Joseph and Sarah Cree The open fields First published in 1994-97 as a series of articles in Cree News by the Cree Family History Society. William Cree and Mary Scott This electronic edition revised and published in 2005 by More accidents - John Cree, Ellen and Thirza Maltsters and iron founders - Francis Cree and Mary King Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Fanny Cree and the boatmen of Newark Oadby Leicester LE2 5RD England © Copyright Mike Spathaky 1994-97, 2005 All Rights Reserved Elizabeth CREE b Collingham, Notts Descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand bap 10 Mar 1850 S Muskham, Notts (three generations) = 1871 Southwell+, Notts Robert -

Tfie LONDON GAZETTE, APRIL 15, 1902

2503 TfiE LONDON GAZETTE, APRIL 15, 1902. War Office, Supernumerary Major \V. M. Sherston, D.S.O. lath April, 1902. Major R. J. B. Hippisley. MEMORANDUM. Ma,jor J. L. Benthall. HIS MAJESTY the King has been Major N. McLean. graciously pleased to approve the formation of Supernumerary Captain G. C. Glyn, D.S.O. a Regiment of Imperial Yeomanry in the East Lieutenant A. H. Gibbs. Biding of Yorkshire, to be designated the East Second Lieutenant H. G. Spencer. Riding of Yorkshire Imperial Yeomanry. Acting Quartermaster R. C. Stephens. Surgeon-Lieutenant-Colonel J. J. Saville. War Office, Veterinary-Lieutenant F. W. Leigh. 15th April, 1902. Suffolk (the Duke of York's Own Loyal Suffolk MEMORANDUM. Hussars), Lieutenant-Colonel (Honorary Major The undermentioned Officers resign their in the Army) E. W. D. Baird. Commissions and receive new Commissions sub- ject to the provisions of the Militia and War Office, Yeomanry Act, 1901, each retaining his present loth April, 1902. rank and seniority, viz.: — Cheshire(Earl o/CAes/er's^Lieutenan'-Cclonel ani HONOURABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY OF Honorary Colonel C. A., Earl of Harrington. LONDON. Major andJBEonorary Lieutenant-Colonel J. Tom- Major John Cecil Wray, retired pay, late Royal kinson. Artillery, to be Major, with seniority from Major H. A. Birley. 14th March, 1900, the date of his appointment Major the Honourable A. de T. Egerton. to the Veteran Company. Dated 20th March, Major (Honorary Captain in the Army) Lord 1902. A. H. Grosvenor. The undermentioned Gentlemen to be Second Major W. B. Brocklehurst. Lieutenants:— Captain and Honorary Major G. Wyndham. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

South Kesteven District Council 2019

South Kesteven District Council 2019 Air Quality Annual Status Report (ASR) In fulfilment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management June 2019 LAQM Annual Status Report 2019 South Kesteven District Council Local Authority Peter Rogers Officer Department Environmental Protection Council Offices St Peter’s Hill Address Grantham Lincolnshire NG31 6PZ Telephone 01476 406080 E-mail [email protected] Report Reference 2019 Annual Status Report number Date June 2019 LAQM Annual Status Report 2019 South Kesteven District Council Executive Summary: Air Quality in Our Area Air Quality in South Kesteven Air pollution is associated with a number of adverse health impacts. It is recognised as a contributing factor in the onset of heart disease and cancer. Additionally, air pollution particularly affects the most vulnerable in society: children and older people, and those with heart and lung conditions. There is also often a strong correlation with equalities issues, because areas with poor air quality are also often the less affluent areas1,2. The annual health cost to society of the impacts of particulate matter alone in the UK is estimated to be around £16 billion3. There is currently one Air Quality Management Area (AQMA) designated within South Kesteven; AQMA No.6 within Grantham that spans the main vehicular route through the town centre. The current AQMA has been declared due to exceedances of the NO2 annual mean and 1-hour objectives. During 2018, South Kesteven monitored NO2 using fifty eight passive NO2 diffusion tubes at thirty five separate locations with no automatic monitoring completed. The NO2 diffusion tube network is in place to monitor NO2 concentrations across the District, monitoring at known hotspot areas and also being used to identify any new hotspot areas. -

Architectural Sculpture

CHAPTER VI ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE We have seen in Chapter III above that there is no Viking date (Chapter IV, p. 41). As a fragment from a shortage of early church sites — both documented and monumental crucifixus, South Leverton 2 will have been presumed — in Nottinghamshire; but unfortunately part of a scene with approximately life-sized figures, not a single stone carrying architectural decoration and located either — like Bitton, Gloucestershire — sensu strictu has yet been recognised as belonging to over the chancel arch or — like that at Headbourne the pre-Viking period. No Nottinghamshire church, Worthy, Hampshire — over a west door (Bryant for example, retains evidence of external decorat- with Hare 2012, 147–50, ills. 67–84; Tweddle et al. ive panels to compare with those found in other 1995, 259–60, ills. 448–50). If the relevant church East Midland counties: at Edenham (Lincolnshire), was the fore-runner of the present All Saints at South Breedon-on-the-Hill (Leicestershire), Barnack (Soke Leverton, then the structural development of that of Peterborough) or Earls Barton (Northampton- fabric affords an explanation for the disturbance of shire).5 Such architectural decoration might have been the presumed rood sculpture: either from the external relatively rare in its time anyway, and Nottinghamshire west wall through the addition of a west tower in churches have been subject to much rebuilding, but the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, or by the its complete absence from the county remains dis- removal of the whole chancel-arch wall though the appointing. It is true that, when discovered in 1980, stylish addition of a grand new chancel of slightly later the impressive late eighth- or early ninth-century date (Pevsner and Williamson 1979, 315–16). -

Grantham Southern Quadrant

Project Promoters: Buckminster Estates, Grantham Lincolnshire County Council, South Kesteven District Council Southern Quadrant Scale: Lincolnshire £200m+ GDV Sector: Opportunity Mixed use of Housing and Retail An opportunity to shape the delivery of the project at an early stage, with a range of direct developer Location: and investment options including development Grantham, Lincolnshire partner/investor and forward funding for identified occupiers. Investment Type: Development partner/investor; An ambitious project to deliver a high quality, forward funding for identified sustainable development of new homes, employment occupiers and retail space stretching from the A1 eastwards around the southern side of the town of Grantham. The Planning Status: opportunity is focussed on the new Garden Village of Allocated in the local plan Spitalgate Heath, one of only fourteen designated by the Government, and a Designer Outlet Village which has www.southkesteven.gov.uk recently been approved through planning. Overview With planning permissions for the employment land and construction of the road infrastructure having been granted Background and decisions to grant consent for the retail Grantham is the largest town in South space and residential properties in place the Kesteven District and is a sub-regionally development opportunities are becoming significant centre with excellent transport immediately investable. links to London and Nottingham. The Existing schemes are in the final stages Southern Quadrant to the south of the of the planning process with further site town is the largest of the development allocations coming forward through the sites identified in the Councils Core South Kesteven Local Plan creating longer Strategy. term investment opportunities The development of the Southern Quadrant The approximate number of units for each will deliver a sustainable new community in phase is: a high quality landscape setting, providing much needed new homes and jobs whilst • Phase 1: 1,212 homes including contributing to the wider regeneration of c. -

181205-JA2 Pet Policy.Indd

Pet Ownership Guidance for North Kesteven District Council tenants GOLD Footprint (This policy conforms to the RSPCA Gold HOUSING 2016 Standard Footprint) 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Pets and the law 3 3. Responsible pet ownership 4 4. Applying to keep a pet 5 5. Reasons for refusing permission 6 6. What your tenancy agreement says about pets 6 7. What constitutes nuisance behaviour by a pet? 7 8. What to do if you are having problems with a neighbours pet 7 9. What action the Authority can take concerning nuisance pets 8 10. What action to take in the case of cruelty or neglect 8 11. Discounted Pet Neutering Scheme 8 12. Free microchipping 9 13. List of local animal welfare organisations: 9 14. Useful contacts for advice and assistance: 10 Foreword North Kesteven is rightly recognised as a great place to live, and we know pets can really add to the quality of life of our residents. Sometimes though, it can be easy to forget about the responsibilities that come with pet ownership, so I welcome this Policy, which makes those responsibilities clear. I hope that the tenants that follow this policy will find the Council helping them enjoy many years of responsible pet ownership, whatever their choice of pet. Councillor Stewart Ogden Executive Board Member Responsible for Housing 3 1. Introduction 1.1 North Kesteven District Council recognises the 2.3 Animal Welfare Act 2006 persons found benefits that responsible pet ownership can guilty of cruelty or neglect may be bring. Pets provide people with companionship, imprisoned and/or fined. -

Summary of Representations Submitted To

Publication of the Coleby Parish Neighbourhood Plan In accordance with the Central Lincolnshire Statement of Community Involvement, the following activities were undertaken in order to publicise the Coleby Parish Neighbourhood Plan: 1. The consultation was published on the North Kesteven District Council website, and included: • The plan and accompanying documents, • Details of where and when the plan can be viewed (paper copies), • Details of how people can comment (electronic and paper), • Details of when comments must be received by, • A statement that representations may include a request to be notified of future stages of the plan, and • The response form. 2. Hard copies of the plan, documents and response form were also made available at the following locations: • The District Council Offices, • Coleby Parish Council, copy available upon request • Libraries in Metheringham and Branston during normal opening hours. 3. Notify specific bodies / individuals: • A number of bodies were consulted as detailed in the table overleaf. 4. Other publication/promotion: • A press release was sent to local media stating where and when the plan could be reviewed, and how to provide formal responses. • All feedback received was posted onto the District Council Website. 1 COLEBY NEIGHBOURHOOD DRAFT PLAN CONSULTATION LIST Organisation Contact Details Date Method Comments Coleby PC & [email protected] 15/06/17 Regulation 16 notification along with all Completed response form from Residents [email protected] the documentation displayed on the PC residents: website: Mr Graham George Millard. http://parishes.lincolnshire.gov.uk/Coleby/ (Resident 1) section.asp?catId=38318 Alexander Cockhill (Resident 3) A notice was displayed on their notice board, with a flyer hand delivered to Parish Iain Cockhill (Resident 4) addresses. -

THE SANITARY FUNCTIONS of COUNTY COUNCILS. General

428 MTDICBALPJTURAL I SANITARY FUNCTIONS OF COUNTY COUNCILS. [FEB. 23, 1895. traces. Then, again, the line between giving IIa faint opal- Reports under the Housing of the'.Working Classes escence," " giving a very slight precipitate," and " giving no Aet. precipitate," is very difficult to draw, especially when no Applications and questions under the Isolation Hos- strength is given for the solutions nor limit of time for the pitals Act. formation ot a precipitate. It would be a very lengthy task Appeals by parish councils in case of default in sani- indeed to point out these defects in detail, but a comparison tary matters on the part of the rural district council. of the British with other more modern Pharmacopceias will 3. Whether any county medical officer of health had been soon show how much more minute are the instructions given appointed. for testing in these latter. In the first place fourteen administrative counties, accord- To these and similar criticisms from a manufacturer's ing to the returns furnished by the respective clerks, have standpoint there are two objections that are likely to be appointed county medical officers of health. These pioneer taken: first, that they are mere details which it is the counties are: business of the manufacturer to attend to; and, secondly, Bedfordshire Lancasllire Surrey that an absolute standard of should be Cheshire London Worcestershire purity set up and Derbyshire Northumberland Yorkshire, N. Riding adlhered to at any cost. To the first objection it may fairly be Durham Shropshire Yorkslhire, -

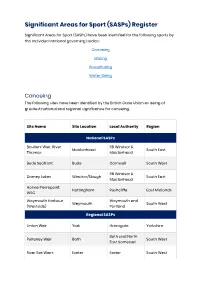

Significant Areas for Sport (Sasps) Register

Significant Areas for Sport (SASPs) Register Significant Areas for Sport (SASPs) have been identified for the following sports by the individual national governing bodies: Canoeing Gliding Parachuting Water Skiing Canoeing The following sites have been identified by the British Cane Union as being of greatest national and regional significance for canoeing. Site Name Site Location Local Authority Region National SASPs Boulters Weir, River RB Windsor & Maidenhead South East Thames Maidenhead Bude Seafront Bude Cornwall South West RB Windsor & Dorney Lakes Windsor/Slough South East Maidenhead Holme Pierrepoint Nottingham Rushcliffe East Midlands WSC Weymouth Harbour Weymouth and Weymouth South West (Westside) Portland Regional SASPs Linton Weir York Harrogate Yorkshire Bath and North Pulteney Weir Bath South West East Somerset River Exe Weirs Exeter Exeter South West River Ure Ripon Harrogate Yorkshire River Washburn Harrogate/Skipton Harrogate Yorkshire River Wey Weybridge Runnymede South East River Wharfe, Harrogate/Skipton Harrogate Yorkshire Appletreewick Shepperton Weir Shepperton Spelthorne South West Gliding The following sites have been identified by the British Gliding Association as being of greatest national and regional significance for gliding. Site Name Site Location Local Authority Region National SASPs Aston Down Chalford Stroud South West Bicester Bicester Cherwell South East Camphill Great Hucklow Derbyshire Dales East Midlands Central Dunstable Dunstable East Bedfordshire Huntingdonshire Gransden Lodge Combourne & South -

Defending Historic Buildings

A M S Defending Historic Buildings ST ANN’S VESTRY HALL, 2 CHURCH ENTRY, LONDON EC4V 5HB Patron: HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES, KG KT Listed Buildings Threatened by Applications to Demolish In 2005 (The Ancient Monuments Society is a mandatory consultee on applications to demolish listed buildings in whole or part in England and Wales.) These statistics cover England and Wales but not Scotland or Northern Ireland. The total number of listed buildings subject to applications to demolish was 127. The total number of listed buildings subject to applications to demolish in Wales was 14. Each entry takes the following format: i) Town / County as applicable. ii) Name and address of building. iii) The grade of listing is given: I, II* or II. iv) The month in which the AMS was informed of the application. v) The date of the building if known. Then the code indicates: C - Application submitted by Council CC -Application submitted by County Council F -Application wholly or partly prompted by fire damage. R - Building threatened by a road scheme Rp -Proposal for "replica" Facade after development. These figures include applications for delisting where the building has been demolished. The name of the local authority is given in parenthesis if it is not clear. Finally the result of the application, if yet determined, is given. ANCIENT MONUMENTS SOCIETY Founded in 1924. Registered Charity No: 209605 In partnership with the Friends of Friendless Churches Tel: 020 7236 3934 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.ancientmonumentssociety.org.uk AMERSHAM, Bucks. Barn, Crown Farm, Whielden St; II; c17; Aug' F; (Chiltern) applic to delist remains.