Adaptive Reuse Models for Dorothea Dix Park Phase II Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosin &Associates

BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK ASSESSMENT ANALYSIS AS OF FEBRUARY 9, 2016 FOR MR. MARTIN HALE PEOPLE FOR GREEN SPACE FOUNDATION INC. 271 CADMAN PLAZA EAST STE 1 PO BOX 22537 BROOKLYN, NY 11201 BY ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 29 WEST 17TH STREET, 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10011 DATE OF REPORT: FEBRUARY 9, 2016 © ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 2016 29 West 17th Street, 2nd Floor ROSIN & ASSOCIATES New York, New York 10011 Tel: (212) 726-9090 Valuation & Advisory Services February 9, 2016 Mr. Martin Hale People For Green Space Foundation Inc. 271 Cadman Plaza East Ste 1 PO Box 22537 Brooklyn, NY 11201 Re: Brooklyn Bridge Park Assessment Analysis Dear Mr. Hale, As requested, we have reviewed the following in order to determine the plausibility of the parameters set forth therein: 1. “Financial Model Update: Public Presentation” presented to the public by Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation (BBPC) report for Brooklyn Bridge on dated July 9, 2015. 2. Analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park completed by Barbara Byrne Denham, titled “Report on Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Financial Model” dated July 2015. Rosin & Associates was hired to perform a market analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park and the surrounding areas in order to determine if the market supports the BBPC model’s assessment base, which features in the Denham Analysis as well as Denham’s own research set forth in her report. It has been a pleasure to assist you in the assignment. If you have any questions concerning the analysis, or if Rosin & Associates can be of further service, please contact us at (212) 726-9090. Respectfully submitted, -

BUNKER MENTALITY CB2 Tells Bloomie to Take Hike

INSIDE BROOKLYN’S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER Including The Downtown News, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper ‘Nut’ gala raises $700G for BAM Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 26 Court St., Brooklyn 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 AD fax 718-834-1713 • NEWS fax 718-834-9278 © 2002 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 12 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 25, No. 51 BWN, DTG, PSG, MID • December 30, 2002 • FREE NEW YEAR’S BLAST! BUNKER MENTALITY CB2 tells Bloomie to take hike By Patrick Gallahue The Brooklyn Papers Calling it a hazard to Downtown Brooklyn and its residents, Community Board 2 and Councilman David Yassky this week came down strongly against the city’s plan to build a new Office of Emergency Management headquarters at 165 Cadman Plaza East, the former home of the American Red Cross. / File photo “On public safety grounds I just do not think this is a viable place for such a sensitive facility as the OEM headquarters next to ex- Plans to put the city’s Office of Emergency Management headquar- tremely sensitive, and quite possi- ters at the Red Cross building site at 165 Cadman Plaza East, have The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn bly, target facilities, namely the come under fire. The Brooklyn Papers / File photos Brooklyn Bridge and the federal courthouse,” Yassky said. OEM headquarters is built there. ceived a cold response from the Besides stating his position at a The OEM proposal is making its community and he pledged to re- GAP fireworks to mark 2003 public hearing before Borough way through the city’s public re- vise the design. -

Self Contained Appraisal Report Prepared

SELF CONTAINED APPRAISAL REPORT BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK - TOBACCO WAREHOUSE (CONVERSION PROPERTY) Part of 51 Water Street N/E/C Water Street & New Dock Street Brooklyn, New York BLOCK 26, PART OF LOT 1 PREPARED FOR: Mr. Charles R. Kamps Executive Director NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services 1CentreStreet, 20th Floor North New York, NY 10007 PREPARED BY: Mr. Matthew J. Guzowski - Principal, Ms. Kathleen Rairden – Senior Vice President Ms. Tonia Vailas – Senior Vice President Goodman-Marks Associates, Inc. 420 Lexington Avenue, Suite 456 New York, NY 10017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Certificate of Appraisal ....................................................................................................5 Summary of Salient Facts and Conclusions ....................................................................7 Appraisal Definitions .......................................................................................................9 Hypothetical Conditions, Extraordinary Assumptions, Limiting Conditions & Jurisdictional Exception..............................................................................................12 Valuation Date/Purpose, Intended Use & Users of the Appraisal/Subject Property Identification & Ownership History..............................................................................14 Survey of Subject Property...........................................................................................16 Site Map of Brooklyn Bridge Park................................................................................17 -

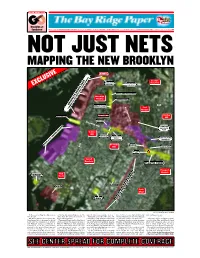

Not Just Nets Mapping the New Brooklyn

INSIDE: PAGES 12-18 Brooklyn at Sundance Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 18 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol.27, No.4 AWP • January 31, 2004 • FREE NOT JUST NETS MAPPING THE NEW BROOKLYN IVE DUMBO S T N U E L K M Brooklyn P C R O EMPIRE STORES Navy Yard WATCHTOWER X A L SHOPPING P E HIGH-RISES E V E E D G L ID A N R O I B T MAYOR’S EMERGENCY BUNKER A N E Y R C Brooklyn L E K -R Heights FEDERAL COURT O L A O I C R R B E M GENERAL POST OFFICE BQE M BANKRUPTCY COURT FLATBUSH AVE. O Fort C Greene Downtown Clinton CRUISE SHIP PIER Hill COURT STREET ATLANTIC AVE.AREA HOUSING DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN PLAN Cobble Hill BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL DORM SCHERMERHORN PACIFIC BAM CULTURAL URBAN RENEWAL DISTRICT ATLANTIC PIERS 8-12: UNDER REVIEW Boerum TERMINAL ATLANTIC CENTER BQE Hill MALL (EXISTING) NETS ARENA SITE Carroll Gardens ATLANTIC YARDS Prospect G Heights Red N FAIRWAY I Hook N O -Z P U WHOLE FOODS E U IKEA N E V Park A Slope H T R U LOWE’S O F Satellite image by Space Imaging It’s the most exciting Brooklyn news in ers that would substantially obscure the where the Nets arena would be located. Lines to Pier 7, and a city-Port Authority skirt scrutiny and debate. -

55 Water Street NE Corner Old Dock and Water Streets

EMPIRE STORES | 55 Water Street NE corner Old Dock and Water Streets Ground Floor Currently Possession Total: 4,883sf at Grade Shinola and Smile To Go Arranged Shinola: 2,883sf at Grade Smile To Go: 2,000sf at Grade Term Space Features Negotiable • Shinola available independently or combined with Smile To Go • ADA access • Located in a 450,000sf development home to West Elm HQ and SoHo House’s first Brooklyn location Neighborhood Tenants Time Out Market, J. Crew, Dumbo House, Cecconi’s, West Elm, FEED Shop & Cafe, Sugarcane, Fellow Barber, Shake Shack, Celestine, The Wing, One Girl Cookies, Seamore’s, Equinox, Grimaldi’s, The One Hotel © 2019 GOODSPACE NYC, LLC 185 Wythe Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11249 EMPIRE STORES | 55 Water Street NE corner Old Dock and Water Streets 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Total 4,883sf at Grade EMERGENCY LIGHT FIXTURE SCHEDULE KEY NOTES SYMBOL MARK DESCRIPTION BTM. OF FIXTURE 1. 44" MIN. EGRESS PATH - REFERENCE ONLY 2. PORTABLE FIRE EXTINGUISHER WITH MIN. RATING OF 5A L E DIRECTIONAL EXIT SIGN 10BC 48" A.F.F. TO TOP OF HANDLE, NOT TO EXCEED 75' Shinola Space TRAVEL DISTANCE FROM OTHER EXTINGUISHER. MUST BE CURRENTLY DATED AND TAGGED BY A LICENSED 1 2 3 4 5 6 FIRE EQUIPMENT COMPANY. COORDINATE EXACT 2,883sf at Grade LOCATION(S) WITH LOCAL AUTHORITY. 3. ADA COMPLIANT LIFT. Smile To Go 2,000sf at Grade K FIRE PROTECTION SYMBOLS SYMBOL MARK DESCRIPTION FE FE WALL MOUNTEC PORTABLE FIRE EXTINGUISHER. RATING OF 5A 10BC L AREA / OCCUPANT CALCULATIONS S.F. -

212-643-8006 Www .Gea-Pllc.Com

212-643-8006 www.gea-pllc.com www.gea-pllc.com About GEA Glickman Engineering Associates (GEA) is one of New York’s top engineering firms, specializing in the innovative design of mechanical, electrical, plumbing and fire Services protection systems for some of the city’s most well-respected companies. The scope of our work includes low to high-rise residential, large-scale retail, hospitality, Mechanical: Heating, Air commercial, light industrial and institutional projects. Conditioning, Ventilation Established in 1996, GEA has grown to be an industry leader by offering clients Electrical: Power, Lighting, superior technical expertise, cutting-edge solutions and forward-thinking design in all Distribution, Low Voltage of our projects—from the most basic to the most sophisticated. Plumbing: Hot and Cold Water, GEA’s principals take pride in personally managing and supervising each and every Distribution, RPZ/Backflow project. Our dedicated and talented roster of engineers and Preventors, Drainage and designers—complemented by the efficiency and professionalism of our support Waste staff—ensure that client needs and expectations are met. Our attention to detail and commitment to excellence allow us to provide comprehensive project coordination Fire Protection: Sprinklers, from design conception through system commissioning. Hydraulic Calculations, Fire Standpipe Through our philosophy of vigorous coordination during the design phase, GEA engineers are able to minimize costly conflicts and changes during the construction Life Safety: Fire -

Anchored Shopping Center in New York City Introducing Admirals Row and Wegmans Supermarket As the Anchor - Under Construction, Delivery Spring 2019

Anchored Shopping Center in New York City Introducing Admirals Row and Wegmans Supermarket as the Anchor - Under Construction, Delivery Spring 2019 • In the heart of a booming Residential, Office, and Retail district GREENPOINT • Surface Parking for 266 spaces and parking garage has Manhattan Bridge 429 spaces • It sits between Dumbo and Williamsburg Brooklyn Bridge BELOW GRADE PARKING • Projected 20,000 workers adjacent at Brooklyn Navy Yard DUMBO WILLIAMSBURG DOCK 72 - EAST FERRY BQE I-278 SITE Exit Exit BROOKLYN HEIGHTS 29 29B Flatbush Ave BQE DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN FORT GREENE BUSHWICK CARROLL GARDENS DEVELOPED BY BOERUM HILL Atlantic Ave CLINTON HILL LEASING AGENT BELOW GRADE PARKING BROOKLYN TRIANGLE - In the heart of much activity and growth LONG ISLAND CITY The Brooklyn Tech Triangle by the Numbers GREENPOINT 13 subway lines 15 WILLIAMSBURG bus lines 523 Bldg 92 Bldg 77 innovation companies Flea Food Employment under Center Green Desk the Archway 77% Duggal Steiner Studios / of firms say more Media Campus Made in NYC Center Greenhouse than half their employees live in Brooklyn Creative Mornings, with IFP + GA Digital DUMBO Green Manufacturing Center / New Lab 127,000 NYU-Poly residents in 1-mile radius Incubator Empire Stores $3.1B Admiral’sSITESite Row Hundreds of economic output digital companies BROOKLYN Brooklyn 18,000 East River DUMBO NAVY YARD Greenway jobs over the next 2 years Ferry Watchtower Properties Commodore 2.2M Barry Park Fort Greene Brooklyn College Town: sf of additional space needed Park Bridge Park 12 universities, -

United States Bankruptcy Court

Case 20-32181-KLP Doc 1106 Filed 11/24/20 Entered 11/24/20 08:40:31 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 20 Case 20-32181-KLP Doc 1106 Filed 11/24/20 Entered 11/24/20 08:40:31 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 20 EXHIBIT A Case 20-32181-KLP Doc 1106 Filed 11/24/20 Entered 11/24/20 08:40:31 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 20 Exhibit A Core/2002 Service List Served as set forth below Description Name Address FAX Email Method of Service Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices 1618 14th Street, NW, LLC Attn: Larry H. Kirsch 202-293-1364 [email protected] Email Counsel to 1618 14th Street, NW, LLC 402 Long Trail Terrace Rockville, MD 20850 Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices Abernathy, Roeder, Boyd & Hullett, P.C. Attn: Paul M. Lopez 214-544-4040 [email protected] Email Counsel to Collin County Tax Assessor/Collector Attn: Larry R. Boyd [email protected] Attn: Emily M. Hahn [email protected] 1700 Redbud Blvd, Ste 300 McKinney, TX 75069 Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices Arent Fox LLP Attn: Mary Joanne Dowd 202-857-6395 [email protected] Email Counsel to Parawin Industries Limited 1717 K St, NW Washington, DC 20006 Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices Ashby & Geddes, P.A. Attn: Gregory A. Taylor 302-654-2067 [email protected] Email Counsel to RetailMeNot, Inc. Attn: Stacy L. Newman [email protected] 500 Delaware Ave, 8th Fl P.O. -

Self-Contained Appraisal Report Prepared

SELF-CONTAINED APPRAISAL REPORT BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK – (CONVERSION PROPERTY) TOBACCO WAREHOUSE & EMPIRE STORES Part of 51 Water Street N/E/C Water Street & New Dock Street Brooklyn, New York BLOCK 26, PART OF LOT 1 PREPARED FOR: Mr. Charles R. Kamps Executive Director NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services 1 Centre Street, 20th Floor North New York, NY 10007 PREPARED BY: Mr. Matthew J. Guzowski - Principal, Ms. Kathleen Rairden – Senior Vice President Ms. Tonia Vailas – Senior Vice President Goodman-Marks Associates, Inc. 420 Lexington Avenue, Suite 456 New York, NY 10017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Certificate of Appraisal ....................................................................................................9 Summary of Salient Facts and Conclusions ..................................................................12 Appraisal Definitions .....................................................................................................15 Hypothetical Conditions, Extraordinary Assumptions, Limiting Conditions & Jurisdictional Exception ...........................................................18 Valuation Date/Purpose, Intended Use & Users of the Appraisal/Subject Property Identification & Ownership History..............................................................................21 Survey of Subject Property...........................................................................................23 Site Map of Brooklyn Bridge Park................................................................................26 -

“Report on Brooklyn Bridge Park's Financial Model,” Wa

July 29, 2015 To Whom it May Concern: The attached document, titled “Report on Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Financial Model,” was prepared by Barbara Byrne Denham in July 2015, to provide an independent third-party objective review of Brooklyn Bridge Park’s (BBP’s) long term financial model. BBP operates under a long-standing mandate to be financially self-sufficient, generating revenues from a limited number of development sites to cover the costs of maintaining and operating the park. In order to ensure that projected revenues meet projected expenses over the life of the Park, BBP staff has created a long-term financial model and presents updates to this model from time to time. The most recent update, from July 2015 can be seen here. Ms. Denham is a well-respected economist with specialties in regional economic issues, real estate valuations and quantitative analytics. She is currently an economist with REIS, the industry leader on providing real estate economics analyses and market data. Previously, she was the chief economist at both Eastern Consolidated and Jones Lang LaSalle, two of the most active real estate brokerage and investment firms in New York City. Her previously published reports have been widely cited in publications including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Crains New York, and a host of other real estate publications. This report presents the independent findings of a months-long analysis conducted by Ms. Denham. It does not represent the opinions of the BBP Board of Directors or staff. Indeed, there are sections of this report that are critical of the BBP model’s assumptions. -

With Phase 1 of the Wharf Nearing Completion, 1.2 Million Additional Square Feet Awarded to Architects and Designers for Phase 2 Construction

WITH PHASE 1 OF THE WHARF NEARING COMPLETION, 1.2 MILLION ADDITIONAL SQUARE FEET AWARDED TO ARCHITECTS AND DESIGNERS FOR PHASE 2 CONSTRUCTION Perkins Eastman DC will Oversee a Collective of Eleven of the Country's Most Prestigious Architects and Designers WASHINGTON, D.C., January 31, 2017 – Hoffman-Madison Waterfront (HMW), the developer of The Wharf, a $2 billion, mile-long neighborhood located on DC's Southwest waterfront, today announced the architects and designers selected to design Phase 2 of the site. The eleven architects comprise one of the most impressive lineups in the nation to design the ambitious second phase of The Wharf. When complete, Phase 2 of The Wharf will feature an additional 1.2 million square feet of mixed-use development including office, residential, marina, and retail space, as well as parks and public spaces, across an approximate half mile of waterfront. Phase 1 is scheduled to open in October 2017. The groundbreaking for Phase 2 will take place in mid- 2018, with an expected completion date in 2021. “It is extraordinarily exciting to be able to announce the team we have selected to design Phase 2 of The Wharf,” said Shawn Seaman, AIA, Principal and Senior Vice President of Development of PN Hoffman. “We have selected a diverse group of locally, nationally, and internationally renowned designers, knowing they will bring their talent and expertise to The Wharf, building a waterfront neighborhood that is an integral part of the city.” "As with everything connected to The Wharf, the architectural design team chosen for Phase 2 reflects our ongoing efforts to achieve excellence while creating a dynamic, authentic, and compelling community," said Peter Cole, Managing Director of Madison Marquette. -

Ground Floor Office Deck

DUMBO’S RIVERFRONT ULTRA MODERN FULL FLOOR WORKSPACES Today DUMBO’s artistic and industrial energies have merged to create New York’s most forward-looking, electric place to live, work, and play. Sprawling riverfront parks and cultural centers like St. Ann’s Warehouse; state- of-the-art office spaces and light-filled family homes in former factory spaces; woodfired pizza and handcrafted ice cream on the picturesque blocks down below. And 10 Jay is at the center of it all. 2 BUILDING FACTS TYPE Mixed-Use Office Building LOCATION 10 Jay Street Brooklyn, NY 11201 NEIGHBORHOOD BUILDING SIZE 10 Stories 221,501 SF DEVELOPERS Glacier Global Partners Triangle Assets ARCHITECT ODA Architecture YEAR BUILT 1897 RENOVATED 2017 3 OFFICE TENANTS / CUSTOMERS COMPANY INDUSTRIES Technology, Advertising, Media, Information COMPANY EMPLOYEES Modern, creative, forward-thinking and technology-focused men and women CAPTIVE AUDIENCE for breakfast meetings, catered lunches, private parties, and happy hour drinks— on-site proximity equates to a significant competitive advantage Built-in crop of dining and drinking “regulars” 10 11 BROOKLYN TECH TRIANGLE 17, 30 0 innovation employees 45% growth from 2012 to 2015 1,350 innovation companies 22% growth from 2012 to 2015 “THE BROOKLYN TECH TRIANGLE, MADE OF Tax Incentives to further UP DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN, , AND THE attract relocating businesses BROOKLYN NAVY YARD, HAS BECOME A MAGNET FOR THE WORLD’S PIONEERING, ENERGETIC, AND CREATIVE ENTREPRENEURS AND HAS EMERGED AS NEW YORK CITY’S LARGEST CLUSTER OF TECH ACTIVITY