04-Brooklyn-Bridge-Park-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WASHINGTON BRIDGE, Over the Harlem River from West 18Lst Street, Borough of Manhattan, to University Avenue, Borough of the Bronx

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 14, 1982, Designation List 159 LP-1222 WASHINGTON BRIDGE, over the Harlem River from West 18lst Street, Borough of Manhattan, to University Avenue, Borough of the Bronx. Built 1886-89; com petition designs by Charles C. Schneider and Wilhelm Hildenbrand modified by Union Bridge Company, William J. McAlpine, Theodore Cooper, and DeLemos & Cordes; chief engineer William R. Hutton; consulting architect Edward H. Kendall. Landmark Site: Manhattan Tax Map Block 2106, Lot 1 in part; Block 2149, Lot 525 in part, consisting of those parts of these ldta upon which the structure and approaches of the bridge rest. The Bronx Tax Map Block 2538, Lot 32 in part; Block 2880, Lots 1 & 250 both in part; Block 2884, Lots 2, 5 & 9 all in part, con sisting of those parts of these lots upon which the structure and approaches of the bridge rest. Boundaries: The Washington Bridge Landmark is encompassed by a line running southward parallel with the eastern curb line of Amsterdam Avenue; a line running eastward which is the extension of the southern curb line of West 181st Street to the point where it crosses Undercliff Avenue; a line running northward parallel with the eastern curb line of Undercliff Avenue; a line running westward from Undercliff Avenue which intersects with the extension of the northern curb lin~ of West 181st Street, to_t~~ point of beginning. On November 18, 1980, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Washington Bridge and the pro posed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No 8.). -

1 Brooklyn Community Board 6 General Board Meeting

BROOKLYN COMMUNITY BOARD 6 GENERAL BOARD MEETING JOHN JAY EDUCATIONAL CAMPUS 237 7TH AVENUE NOVEMBER 13, 2013 ATTENDANCE PRESENT: E. ANDERSON R. BASHNER P. BELLENBAUM N. BERK-RAUCH J. BERNARD F. BROWN E. CAUSIL-RODRIGUEZ N. COX E. FELDER P. FLEMING Y. GIRELA D. GIULIANO R. GRAHAM V. HERAMIA J. HEYER G. KELLY A. KRASNOW D. KUMMER R. LEVINE S. LONIAL R. LUFTGLASS D. MAZZUCA A. MCKNIGHT T. MISKEL C. PIGOTT L. PINN M. RACIOPPO G. REILLY R. RIGOLLI M. RUIZ M. SCOTT M. SHAMES E. SHIPLEY M. SILVERMAN B. SOLOTAIRE L. SONES E. SPICER J. STRABONE J. THOMPSON S. TURET D. WILLIAMS EXCUSED: SR. R. CERVONE M. KOLMAN P. MINDLIN D. SCOTTO ABSENT: D. BRAVO C. CALABRESE H. HUGHES H. LINK G. O’CONNELL, JR. GUESTS: L. JACOBSON, BOROUGH PRESIDENT MARKOWITZ’ REPRESENTATIVE M. SARCI, COUNCIL MEMBER LEVIN’S REPRESENTATIVE E. ERTINGER, COUNCIL MEMBER LANDER’S REPRESENTATIVE T. SGRIGNOLI, ASSEMBLY MEMBER BRENNAN’S REPRESENTATIVE T. SMITH, ASSEMBLY MEMBER MILLMAN’S REPRESENTATIVES HON. DANIEL SQUADRON, STATE SENATOR R. YOUNG, STATE SENATOR SQUADRON’S REPRESENTATIVE P. RHÉAUME, CONGRESS MEMBER CLARKE’S REPRESENTATIVE Complete list of meeting attendees on file at District Office. 1 Chairperson Daniel Kummer called the meeting to order at 6:47pm. ADOPTION OF MINUTES Board Member Peter Fleming made a motion to accept the minutes of the October’s general meeting, seconded by Board Member Gary Reilly. VOTE: 30 YEAS, 0 NAYS, 0 ABSTENTIONS MOTION PASSED UNANIMOUSLY TIME: 6:48 P.M. __________________________________________________________________________________________ “CORE OF THE APPLE AWARD” In recognition of their service to the various communities of the district, especially during Hurricane Sandy, Deputy Inspector Jeffrey Schiff, former Commanding Officer of the 76th Police Precinct and James Proscia, former District Superintendent of Sanitation BK6 garage were presented with the CB6 “Core of the Apple Award.” Salutary remarks were made by Chairperson Daniel Kummer. -

Wanderings Newsletter of the OUTDOORS CLUB INC

Wanderings newsletter of the OUTDOORS CLUB INC. http://www.outdoorsclubny.org ISSUE NUMBER 108 PUBLISHED TRI-ANNUALLY Jul-Oct 2014 The Outdoors Club is a non-profit 501(c) (3) volunteer-run organization open to all adults 18 and over which engages in hiking, biking, wilderness trekking, canoeing, mountaineering, snowshoeing and skiing, nature and educational city walking tours of varying difficulty. Individual participants are expected to engage in activities suitable to their ability, experience and physical condition. Leaders may refuse to take anyone who lacks ability or is not properly dressed or equipped. These precautions are for your safety, and the wellbeing of the group. Your participation is voluntary and at your own risk. Remember to bring lunch and water on all full day activities. Telephone the leader or Lenny if unsure what to wear or bring with you on an activity. Nonmembers pay one-day membership dues of $3. It is with sorrow that we say goodbye to Robert Kaye, the brother of Alan Kaye, who died in January. We have been able to keep the dues the same, and publish the Newsletter because of Robert’s benevolence to the Club. Robert wanted to make sure that the Club would continue after Alan’s death. Please join Bob Susser and Helen Yee on Saturday, October 18th, at the New York Botanical Gardens for a memorial walk in honor of Robert Kaye. CHECK THE MAILING LABEL ON YOUR SCHEDULE FOR EXPIRATION DATE! RENEWAL NOTICES WILL NO LONGER BE SENT. It takes 4-6 weeks to process your renewal. Some leaders will be asking members for proof of membership, so please carry your membership card or schedule on activities (the expiration date is on the top line of your mailing label). -

Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation D/B/A Brooklyn Bridge Park Meeting of the Directors Held at 334 Furman Street Brooklyn, NY

Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation d/b/a Brooklyn Bridge Park Meeting of the Directors Held at 334 Furman Street Brooklyn, NY December 5, 2018 MINUTES The following members of the Board of Directors were present: Alicia Glen – Chair Joanne Witty – Vice Chair Margaret Anadu Peter Aschkenasy Martin Connor Henry B. Gutman James Katz Stephen Levin* Stephen Merkel Rebecca Miller Tucker Reed Susannah Pasquantonio Andrea Phillips Mitchell Silver William Vinicombe Edna Wells Handy * Director Levin not present at all times Also present was the staff of Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation (“BBP”), the Mayor’s Office and members of the press and public. Chair Glen called the meeting to order at approximately 11:00 am. Suma Mandel, Secretary and General Counsel of BBP, served as secretary of the duly constituted meeting and confirmed that a quorum was present. Prior to proceeding with the agenda items, Chair Glen welcomed the Board, BBP Staff and members of the public. She also welcomed new Director Andrea Phillips. 1. Approval of Minutes Upon motion duly made and seconded, the minutes of the October 10, 2018 Board of Directors meeting were unanimously1 approved. 2. Presentation of the President’s Report (Non-Voting Item) 1 Director Levin was not present for this vote 1 Eric Landau, BBP’s President, updated the Board on the Park’s progress, including: (i) the Pier 6 development sites; (ii) the upcoming preventative maritime maintenance RFP; (iii) Pier 2 Uplands construction; (iv) the ongoing planning process for the Brooklyn Bridge Plaza and Squibb Park Pool; and (v) the anticipated installation of an outdoor public squash court on Pier 5 by Public Squash. -

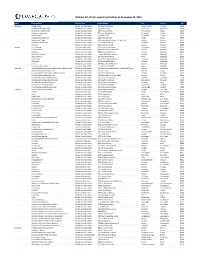

Facilities List for Website.Xlsx

Address list of Core operating facilities at December 31, 2019 State Facility Name Facility Type Street Address City County Zip Alabama Avalon Place Skilled Nursing Facility 200 Alabama Avenue Muscle Shoals Colbert 35661 Brookshire (fka Westside) Skilled Nursing Facility 4320 Judith Lane Huntsville Madison 35805 Canterbury Health Center Skilled Nursing Facility 1720 Knowles Road Phoenix City Russell 36867 Cottage of the Shoals Skilled Nursing Facility 500 John Aldridge Drive Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Keller Landing Skilled Nursing Facility 813 Keller Lane Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Lynwood Nursing Home Skilled Nursing Facility 4164 Halls Mill Road Mobile Mobile 36693 Merrywood Lodge Skilled Nursing Facility 280 Mount Hebron Road, P.O. Box 130 Elmore Elmore 36025 Northside Health Care Skilled Nursing Facility 700 Hutchins Avenue Gadsden Etowah 35901 River City Skilled Nursing Facility 1350 14th Avenue SE Decatur Morgan 35601 Arizona Austin House Assisted Living Facility 195 South Willard Street Cottonwood Yavapai 86326 Encanto Palms Assisted Living Facility 3901 West Encanto Boulevard Phoenix Maricopa 85009 L'Estancia Skilled Nursing Facility 15810 South 42nd Street Phoenix Maricopa 85048 Maryland Gardens Skilled Nursing Facility 31 West Maryland Avenue Phoenix Maricopa 85013 Mesa Christian Skilled Nursing Facility 255 West Brown Road Mesa Maricopa 85201 Palm Valley Skilled Nursing Facility 13575 West McDowell Road Goodyear Maricopa 85338 Ridgecrest Skilled Nursing Facility 16640 North 38th Street Phoenix Maricopa 85032 Sun City Skilled Nursing -

1. After Opening the File, Click the "Bookmark" Icon on the Left Side of the Screen

Volunteer Site Locations to File Your Taxes Yourself for Free Instructions for Creating Bookmarked State Pages: 1. After opening the file, click the "Bookmark" icon on the left side of the screen. 2. You will then see the list of state abbreviations on the left-side column; click on the page(s) that correspond to your state to find the listings for your state. 3. You can also click the Search Box above the list to look for specific information (city, zip code, etc.). Last Updated 3/2/2012 1 Volunteer Site Locations to File Your Taxes Yourself for Free Provider State County Phone Dates Languages Appointment United Bank - 137 N Main St 1/17/2012 - Atmore, AL 36502 AL Escambia (251) 446-6000 4/14/2012 English Required BancorpSouth-Roving Site- 4680 Highway 280 East 1/17/2012 - Birmingham, AL 35242 AL Shelby (205) 437-2712 4/16/2012 English Required UWCA - Main-- 3600 8TH AVE South 1/17/2012 - Birmingham, AL 35232 AL Jefferson (888) 421-1288 4/17/2012 English Required UWCA Virginia College 488 Palisades Blvd 1/23/2012 - Birmingham, AL 35209 AL Jefferson (888) 421-1266 4/17/2012 English Required Clinton L Johnson Center - 1655 Eagle Dr 1/16/2012 - Mobile, AL 36605 AL Mobile (251) 470-0372 4/17/2012 English Required Goodwill Easter Seals - Cottage Hill - 5013 Cottage Hill Road 1/17/2012 - Mobile, AL 36609 AL Mobile (251) 300-6270 4/17/2012 English Required Mobile Senior Community Center - 3201 Hillcrest Rd 2/6/2012 - Mobile, AL 36695 AL Mobile (251) 574-7787 4/16/2012 English Required CAA of Monroe County 11 Hines Street 1/16/2012 - Monroeville, -

IN NEW YORK CITY January/February/March 2019 Welcome to Urban Park Outdoors in Ranger Facilities New York City Please Call Specific Locations for Hours

OutdoorsIN NEW YORK CITY January/February/March 2019 Welcome to Urban Park Outdoors in Ranger Facilities New York City Please call specific locations for hours. BRONX As winter takes hold in New York City, it is Pelham Bay Ranger Station // (718) 319-7258 natural to want to stay inside. But at NYC Pelham Bay Park // Bruckner Boulevard Parks, we know that this is a great time of and Wilkinson Avenue year for New Yorkers to get active and enjoy the outdoors. Van Cortlandt Nature Center // (718) 548-0912 Van Cortlandt Park // West 246th Street and Broadway When the weather outside is frightful, consider it an opportunity to explore a side of the city that we can only experience for a few BROOKLYN months every year. The Urban Park Rangers Salt Marsh Nature Center // (718) 421-2021 continue to offer many unique opportunities Marine Park // East 33rd Street and Avenue U throughout the winter. Join us to kick off 2019 on a guided New Year’s Day Hike in each borough. This is also the best time to search MANHATTAN for winter wildlife, including seals, owls, Payson Center // (212) 304-2277 and eagles. Kids Week programs encourage Inwood Hill Park // Payson Avenue and families to get outside and into the park while Dyckman Street school is out. This season, grab your boots, mittens, and QUEENS hat, and head to your nearest park! New York Alley Pond Park Adventure Center City parks are open and ready to welcome you (718) 217-6034 // (718) 217-4685 year-round. Alley Pond Park // Enter at Winchester Boulevard, under the Grand Central Parkway Forest Park Ranger Station // (718) 846-2731 Forest Park // Woodhaven Boulevard and Forest Park Drive Fort Totten Visitors Center // (718) 352-1769 Fort Totten Park // Enter the park at fort entrance, north of intersection of 212th Street and Cross Island Parkway and follow signs STATEN ISLAND Blue Heron Nature Center // (718) 967-3542 Blue Heron Park // 222 Poillon Ave. -

Rosin &Associates

BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK ASSESSMENT ANALYSIS AS OF FEBRUARY 9, 2016 FOR MR. MARTIN HALE PEOPLE FOR GREEN SPACE FOUNDATION INC. 271 CADMAN PLAZA EAST STE 1 PO BOX 22537 BROOKLYN, NY 11201 BY ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 29 WEST 17TH STREET, 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10011 DATE OF REPORT: FEBRUARY 9, 2016 © ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 2016 29 West 17th Street, 2nd Floor ROSIN & ASSOCIATES New York, New York 10011 Tel: (212) 726-9090 Valuation & Advisory Services February 9, 2016 Mr. Martin Hale People For Green Space Foundation Inc. 271 Cadman Plaza East Ste 1 PO Box 22537 Brooklyn, NY 11201 Re: Brooklyn Bridge Park Assessment Analysis Dear Mr. Hale, As requested, we have reviewed the following in order to determine the plausibility of the parameters set forth therein: 1. “Financial Model Update: Public Presentation” presented to the public by Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation (BBPC) report for Brooklyn Bridge on dated July 9, 2015. 2. Analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park completed by Barbara Byrne Denham, titled “Report on Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Financial Model” dated July 2015. Rosin & Associates was hired to perform a market analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park and the surrounding areas in order to determine if the market supports the BBPC model’s assessment base, which features in the Denham Analysis as well as Denham’s own research set forth in her report. It has been a pleasure to assist you in the assignment. If you have any questions concerning the analysis, or if Rosin & Associates can be of further service, please contact us at (212) 726-9090. Respectfully submitted, -

Brooklyn Bridge Park - Case Study

BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK - CASE STUDY URBAN REGENERATION KSB 1 2 ANNOTATED OUTLINE – BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK - CASE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENT Summary 5 Background 6 The Process 7 Project Outcomes 8 Challenges 9 Lessons Learned 11 Sources 12 URBAN REGENERATION KSB 3 1 SUMMARY PROJECT & LOCATION Brooklyn, New York City, USA LAND-BASED Ongoing operations & maintenance of public ame- FINANCING INSTRUMENT nities funded by PILOT (Payment in lieu of property USED taxes); out-lease of excess government-owned land TOTAL PROJECT COST US$355 million 85-acre (34 hectares) of former industrial waterfront LAND AREA land along 1.3 miles of the Brooklyn side of the East River Creation of an iconic park with resilient, world-class design and construction standards, serving locals and visitors; increase in land value and therefore BENEFITS TO THE CITY property taxes in adjacent neighborhoods; enhance the quality of life in surrounding neighborhoods in the borough; financially self-sustaining (i.e., maintained at no cost to the city) ANNUAL O&M BUDGET US$16 million (2016) In the early 1980s, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) decided to cease all cargo ship operations along Brooklyn’s Piers 1 to 6 due to a decline in use, as cargo was increasingly going to other ports. As a result, the piers became a barren, post-industrial site with little activity. Even so, the area had significant potential for reuse, in part due to its panoramic views of the Manhattan skyline across the East River. In the 1990s, PANYNJ announced plans to sell the land for commercial development. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

Brooklyn Bridge Park Sample Location Guide

BSL CLASSROOM LOCATION GUIDE BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK A BIT OF HISTORY FIRST! In 1642, the first ferry landing opened on the land that is now Brooklyn Bridge Park's Empire Fulton Ferry section. As the 18th century came to a close, additional ferry services were added to this waterfront community, including docking points for the "Catherine Street Ferry" and the first steamboat ferry landing that was created by Robert Fulton, which eventually became known as the Fulton Ferry Landing. The community continued to grow into the 19th century as Brooklyn Heights developed into a residential neighborhood, eventually becoming one of America's first suburbs. In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was opened. Brooklyn Bridge Park is an 85-acre (34 ha) park on the Brooklyn side of the East River in New York City, next to the Brooklyn Bridge. From north to south, the park includes the preexisting Empire–Fulton Ferry and Main Street Parks; the historic Fulton Ferry Landing; and Piers 1–6, which contain various playgrounds and residential developments. The park also includes Empire Stores and the Tobacco Warehouse, two 19th-century structures, and is a part of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, a series of parks and bike paths around Brooklyn Today, Brooklyn Bridge Park is a world-class waterfront park with rolling hills, riverfront promenades, lush gardens, and spectacular city views. 1 Page Brooklyn School of Languages, LLC 16 Court Street, 34th Floor Brooklyn, NY 11241 USA Email:[email protected] www.brooklynschooloflanguages.comwww.facebook.com/pages/brooklyn-school-of-languages.com -

The New York City Waterfalls

THE NEW YORK CITY WATERFALLS GUIDE FOR CHILDREN AND ADULTS WELCOME PLAnnING YOUR TRIP The New York City Waterfalls are sited in four locations, and can be viewed from many places. They provide different experiences at each site, and the artist hopes you will visit all of the Waterfalls and see the various parts of New York City they have temporarily become part of. You can get closest to the Welcome to THE NEW YORK CIty WATERFALLS! Waterfalls at Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in DUMBO; along the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway, north of the Manhattan Bridge; along the Brooklyn The New York City Waterfalls is a work of public art comprised of four Heights Promenade; at Governors Island; and by boat in the New York Harbor. man-made waterfalls in the New York Harbor. Presented by Public Art Fund in collaboration with the City of New York, they are situated along A great place to go with a large group is Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in Brooklyn, which is comprised of 12 acres of green space, a playground, the shorelines of Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Governors Island. picnic benches, as well as great views of The New York City Waterfalls. These Waterfalls range from 90 to 120-feet tall and are on view from Please see the map on page 18 for other locations. June 26 through October 13, 2008. They operate seven days a week, You can listen to comments by the artist about the Waterfalls before your from 7 am to 10 pm, except on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when the visit at www.nycwaterfalls.org (in the podcast section), or during your visit hours are 9 am to 10 pm.