3.13 Dungeness River and Tributaries Recommendations Page 3.13-1 3.13 DUNGENESS RIVER and TRIBUTARIES RECOMMENDATIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dungeness River Targeted Watershed Initiative FINAL REPORT

Dungeness River Targeted Watershed Initiative FINAL REPORT For E.P.A. Targeted Watershed Grant WS‐97098101‐0 Prepared By: Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe December 2009 FIGURES Figure 1. Dungeness Watershed on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington. ................................. 4 Figure 2. Dungeness Bay shellfish closure areas. ........................................................................ 6 Figure 3. Phase 1 MST (Ribotyping) sampling locations.............................................................. 9 Figure 4. Phase 2 MST (Bacteroides Target Specific PCR) sampling locations. ......................... 10 Figure 5. Mycoremediation Demonstration Site. ...................................................................... 11 Figure 6. Construction of Mycoremediation Demonstration Site............................................. 12 Figure 7. Schematic of Biofilitration Cells, with native plants and fungi in the Treatment cell and native plants only in the Control. Inflow water is split with equal volumes and fed to the two cells (not to scale). ........................................................ 13 Figure 8. Ground‐breaking excavation at the rain garden site, Helen Haller Elementary School, Sequim, WA.................................................................................................... 15 Figure 9. TWG fresh water monitoring stations and DOH marine monitoring stations. .......... 18 Figure 10. Fecal Coliform Concentration (CFU/100 ml) over 6‐Month Time Period (mean +/‐ standard deviation)................................................................................... -

Delineation of the Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone

Delineation of the Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone River Mouth to Canyon Creek Byron Rot Pam Edens Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe October 1, 2008 Acknowledgements This report was greatly improved from comments given by Patricia Olson, Department of Ecology, Tim Abbe, Entrix Corp, Joel Freudenthal, Yakima County Public Works, Bob Martin, Clallam County Emergency Services, and Randy Johnson, Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe. This project was not directly funded as a specific grant, but as one of many tribal tasks through the federal Pacific Coastal Salmon fund. We thank the federal government for their support of salmon recovery. Cover: Roof of house from Kinkade Island in January 2002 flood (Reach 6), large CMZ between Hwy 101 and RR Bridge (Reach 4, April 2007), and Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone map, Reach 6. ii Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………….1 Legal requirement for CMZ’s……………………………………….1 Terminology used in this report……………………………………..2 Geologic setting…………………………………………………......4 Dungeness flooding history…………………………………………5 Data sources………………………………………………………....6 Sources of error and report limitations……………………………...7 Geomorphic reach delineation………………………………………8 CMZ delineation methods and results………………………………8 CMZ description by geomorphic reach…………………………….12 Conclusion………………………………………………………….18 Literature cited……………………………………………………...19 iii Introduction The Dungeness River flows north 30 miles and drops 3800 feet from the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The upper watershed south of river mile (RM) 10 lies entirely within private and state timberlands, federal national forests, and the Olympic National Park. Development is concentrated along the lower 10 miles, where the river flows through relatively steep (i.e. gradients up to 1%), glacial and glaciomarine deposits (Drost 1983, BOR 2002). -

Harlequin Happenings

HARLEQUIN HAPPENINGS Newsletter of the Olympic Peninsula Audubon Society (OPAS) Www.olympicpeninsulaaudubon.org (www.olybird.org) Clallam County, Washington A Chapter of the National Audubon Society Issue 1 Jan-Feb 2017 Promoting Birding and Conservation as Community Educators, Volunteers, and Stewards OPAS Programs for January and February by Bob Boekelheide January 18, 2017, 7 p.m. at the Dungeness River Audubon Center, “The Natural World Always has a Story to Share - Celebrating What is Right with the World!” Presented by Alan Bauer. Alan Bauer is a profes- sional photographer, specializing in the natu- ral history of the Pacific Northwest. His excellent photographs have ap- peared in numerous Sooty Grouse magazines, newspa- Photo by Alan Bauer pers, books, and even in a special exhibit about spiders at Wood- February 15, 2017, 7 p.m. at the Dungeness River Audubon Center , "OPAS Member Photo Night 2017", land Park Zoo in Seat- tle. As Alan says, “The Organized by Dow Lambert. greatest value of my Time for our annual members' photo show! Do you have photographic art is to photos of birds you would like to share with others? better educate people Lucky for you, because other OPAS members want to about the beauty sur- see them, too. Alan Bauer rounding us.” Please submit your digital photos to Dow Lambert, who Celebrate what is right has generously offered to assist us projecting the imag- with the world! Sometimes we need to slow down, look es. If you wish to offer your photos for the evening, more closely, and appreciate beauty right around us. -

Physical Processes, Human Impacts, and Restoration Issues of the Lower Dungeness River

PHYSICAL PROCESSES, HUMAN IMPACTS, AND RESTORATION ISSUES OF THE LOWER DUNGENESS RIVER Clallam County, Washington Prepared for Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe by the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation May 2002 United States Department of the Interior The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to tribes. Bureau of Reclamation The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Physical Processes, Human Impacts, and Restoration Issues of the Lower Dungeness River Clallam County, Washington Report Prepared By U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation TECHNICAL SERVICE CENTER Denver, Colorado Water Resources Services Division Sedimentation & River Hydraulics Group Jennifer A. Bountry, Hydraulic Engineer Timothy J. Randle, Hydraulic Engineer and Geotechnical Division Seismotectonics and Geophysics Group Lucille A. Piety, Geologist AND PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGIONAL OFFICE Boise, Idaho Resource & Technical Services Geology, Exploration, and Instrumentation Group Richard A. Link, Regional Geologist List of Peer Reviewers The following Bureau of Reclamation personnel peer reviewed this document. Dr. Daniel Levish, Geologist Flood Hydrology Group Technical Service Center, Denver, Colorado Dr. Jianchun Huang, Hydraulic Engineer Sedimentation and River Hydraulics Group -

PIONEER DAYS at OLD DUNGENESS* the History As

PIONEER DAYS AT OLD DUNGENESS* The history as related dates back to the time when Captain Vancouver, a navigator and explorer, named Dungeness- "New Dungeness" -because. of the similarity to a harbor on the southern coast of England of that name. It is not generally known that Port Angeles was named False Dungeness, because of a similar sand spit which encloses its harbor, until a Spanish navigator was driven into the harbor for refuge from a fierce gale and so it derived its name- "The Port of the Angeles" -later being officially named Port Angeles. In the vicinity of Dungeness as the earliest settlers found it in 1852, there was a heavy growth of fir and cedar timber, some of which stood as late as 1914, when it was logged off by the Dungeness Logging Co., operated by N. 1. Peterson, although the lowlands near the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound have always been fringed, with willows, alder, maple and under brush not of high value for lumber purposes. .Puget Sound derived its name from a man named Puget, a member of the crew of Captain Vancouver's ship. In 1852 the settlement of Dungeness was located on what was called Whisky Flats, at the mouth of the Dungeness River. Indians in strong tribes peopled the beaches, their village being on the sand spit later known as Clines Spit. Their dead were buried in shallow graves on top of the ground similar to the mounds of the Dakotas. A few were buried near the edge of the high bluff near the Mc Almond and Abernathy homesteads and relics of these inhabitants are often, turned up by the plow, since that soil has been put to use for farming purposes. -

Middle Dungeness River Olympic National Forest

Middle Dungeness River Subwatershed Restoration Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest USDA Forest Service Watershed Condition Framework FY2012 WATERSHED RESTORATION ACTION PLAN Middle Dungeness River Olympic National Forest Summary Watershed Name and HUC Middle Dungeness River, 171100200306 General Location The Middle Dungeness River watershed is part of the larger Dungeness Watershed and is located near Sequim, Washington. The Olympic National Forest boundary is approximately 8 miles south of Sequim, on the Olympic Peninsula. Other nearby towns includes Port Angeles and Port Townsend. The Middle Dungeness River watershed drains into the Dungeness River, which flows north 10.8 miles from the forest boundary into the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the greater Puget Sound basin. Other fish-bearing streams that are within the Middle Dungeness watershed include Rock, Canyon, Pats, and Caraco Creeks. Middle Dungeness Watershed Restoration Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest Total Watershed Area Total Acres: 18,664 National Forest area within watershed: 45 percent Watershed Characterization General Physiography The Middle Dungeness 6th field watershed is part of the larger Dungeness River watershed. It originates in the moderate relief glaciated lower portion of the Olympic Mountains, with elevations reaching from 5200 feet in the southwest corner within the Buckhorn Wilderness to 300 feet along the Dungeness River near State Highway 101. The southern boundary of the watershed follows an elevation ranging from 3000 to 3500 feet, and the elevation at the forest boundary is approximately 1200 feet. It encompasses the mainstem Dungeness River from the confluence of the Gray Wolf River downstream to well below the National Forest boundary. -

2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Olympic Peninsula Landscapes, And

Chapter 2.1 Natural Environment Page 2.1-1 2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Olympic Peninsula landscapes, and the region’s flora and fauna, have been shaped by the geology and climatic history of the region. The landscapes have been reworked by the persistent, long-term action of gradual environmental changes such as glaciation and mountain-building. They have responded to erratic, catastrophic events, such as major floods, fires, and the breaching of glacial lakes. And they evidence the pervasive effects of human influences. The wildlife and plantlife of the peninsula reflect this long, complex, and significantly altered character. This section discusses the many factors that define the current condition of the natural environment of WRIA 18. This is a diverse area with important differences across its full extent. Consequently, the discussion below contains some information that is generally applicable to the entire planning area. In addition, much work has been done in specific areas within WRIA 18 that makes it possible to present more detailed information relating to portions of the WRIA, especially in distinguishing between East WRIA 18 and West WRIA 18. Where possible and appropriate, information here is presented separately for these eastern and western portions. 2.1.1 Geography West WRIA 18 – Elwha Morse Planning Area West WRIA 18 (WRIA 18W) includes, on the west, the Elwha River and its tributaries, Morse Creek on the east, and the smaller, urban drainages between, including Dry, Tumwater, Valley, Peabody, White, Ennis, and Lees creeks. The headwaters of the Elwha River and Morse Creek lie in the Olympic Mountains. The smaller streams originate in foothills to the north of the main Olympic range and along the northern boundary of Olympic National Park. -

Dungeness River Watershed Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest

Dungeness River Watershed Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest WATERSHED ACTION PLAN For Olympic National Forest Lands within the Dungeness River Watershed 1711002003 September 22, 2016 Dungeness River Watershed Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest The Dungeness watershed has been the focus for numerous committees, studies, and government projects to recover depleted wild stocks of salmon, restore salmon habitat, improve water quality and the overall condition of the watershed. The Olympic National Forest (ONF) has participated with other government agencies, citizens, and stakeholders to develop long-term management of the river and its resources, outline watershed restoration priorities, and implement the actions. This plan contains an aquatic and terrestrial watershed restoration strategy that incorporates recreational opportunities on the Olympic National Forest in the Dungeness 5th field watershed. The plan identifies restoration actions needed to correct known problems and help to put National Forest System (NFS) lands on a trajectory to improve the watershed condition. The 179,300 acre watershed and project analysis area includes both public and privately-owned lands, but with a primary focus on NFS lands. The Dungeness River begins in the snow fields at the southeast face of Mt. Mystery and flows through the foothills across the Sequim-Dungeness Valley, and enters the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The watershed is a municipal water supply and within close proximity of Sequim, Washington. The Dungeness River serves as crucial refugia for maintaining and recovering four species of fish listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act: Puget Sound Chinook, Puget Sound steelhead, Hood Canal summer chum, and Coastal Puget Sound bull trout. -

Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead Within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment Doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-128 Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128 March 2015 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC series to issue scientific and technical publications. Manuscripts have been peer reviewed and edited. Documents published in this series can be cited in the scientific and technical literature. The Northwest Fisheries Science Center’s NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC series continues the NMFS- F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest and Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which subsequently was divided into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The latter center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC series. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Reference this document as follows: Myers, J.M., J.J. Hard, E.J. Connor, R.A. Hayman, R.G. Kope, G. Lucchetti, A.R. Marshall, G.R. Pess, and B.E. Thompson. 2015. Identifying historical populations of steelhead within the Puget Sound distinct population segment. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS- NWFSC-128. doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-128 Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128 James M. -

WRIA 18: Elwha-Dungeness

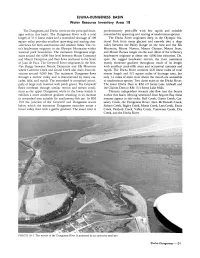

ElWHA-DUNGENESS BASIN Water Resource Inventory Area 18 The Dungeness and Elwha rivers are the principal drain predominantly pool-riffle with few rapids and suitable ages within this basin. The Dungeness River with a total streambed for spawning and rearing of anadromous species. length of 31.9 linear miles and a watershed drainage of 198 The Elwha River originates deep in the Olympic Na square miles provides excellent spawning and rearing char tional Park from many glaciers and extends into a deep acteristics for both anadromous and resident fishes. The riv valley between the Bailey Range on the west and the Elk er's headwaters originate in the Olympic Mountains within Mountain, Mount Norton, Mount Christie, Mount Scott, national park boundaries. The mainstem Dungeness origi and Mount Barnes ranges on the east. Most of the tributary nates around the 4,000 foot level between Mount Constance headwaters originate at about the 4,000-foot elevation. De and Mount Deception and then flows northeast to the Strait spite the rugged headwater terrain, the river maintains of Juan de Fuca. The Greywolf River originates in the Nee mostly moderate gradient throughout much of its length dles Range between Mount Deception and Elk Mountain with excellent pool-riffle areas and occasional cascades and where Cameron Creek and Grand Creek also drain from ele rapids. The Elwha River contains 44.8 linear miles of total vations around 4,000 feet. The mainstem Dungeness flows stream length and 321 square miles of drainage area, but through a narrow valley and is characterized by many cas only 3.4 miles of main river above the mouth are accessible cades, falls, and rapids. -

Dungeness-Elwha Watershed Washington

Washington Dungeness-Elwha Watershed HUC: 17110020 Rapid Watershed Assessment This assessment involves the collection of quantitative and qualitative information to develop a watershed profile, sufficient analysis of that information to make qualitative statements as to resource concerns and conditions, and the generation of information with which to make decisions about conservation needs and recommendations. These assessments are conducted through the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology and by conservation planning teams working within the watershed, meeting with landowners and conservation groups, inventorying agricultural areas, assessing current levels of resource management, identifying conservation recommendations and, making qualitative estimates of the impacts of conservation on local resource concerns. September 25, 2006 1 Dungeness - Elwha Watershed Introduction 807,954 Total Acrea HUC# 17110020 The Dungeness River Watershed is located in the northwest corner of Washington State, on the northeast part of the Olympic Peninsula. The Dungeness- Elwha, 8-Digit Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) subbasin is 807,954 acres in size. The watershed is 25% privately owned and 75% publicly owned. The majority of the watershed is forest and open water. Cropland is located mostly in the lower elevations with expansion, by land-clearing, into the foothills. Agricultural enterprises include hay, grain, berries, orchard fruits, and grass turf. The cities of Sequim and Port Angeles make up the largest urban area in the watershed. Most of the watershed is located in Clallam County, with the upper watershed located in Jefferson County. Major resource concerns are soil erosion on forest roads, streambank erosion, impaired water quality, forest health issues, invasive weeds, poor pasture condition, and urbanization issues associated with conversion of cropland. -

Chapter 1. Coastal Recovery Unit—Olympic Peninsula Critical Habitat Unit Table of Contents

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 1. Coastal Recovery Unit—Olympic Peninsula Critical Habitat Unit Table of Contents 1.1. Dungeness River Critical Habitat Subunit ..................................................................... 17 1.2. Elwha River Critical Habitat Subunit ............................................................................. 21 1.3. Hoh River Critical Habitat Subunit ................................................................................ 31 1.4. Queets River Critical Habitat Subunit ............................................................................ 39 1.5. Quinault River Critical Habitat Subunit ......................................................................... 45 1.6. Skokomish River Critical Habitat Subunit ..................................................................... 51 1.7. Hood Canal Critical Habitat Subunit ............................................................................. 59 1.8. Strait of Juan de Fuca Critical Habitat Subunit .............................................................. 63 1.9. Pacific Coast Critical Habitat Subunit ........................................................................... 69 1.10. Chehalis River / Grays Harbor Critical Habitat Subunit ................................................. 77 15 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 1 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 1. Olympic Peninsula Critical