Final Olym Fmp 11212005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities

NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN THE FIRST 10 YEARS (1994–2003) Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities Lita P. Buttolph, William Kay, Susan Charnley, Cassandra Moseley, and Ellen M. Donoghue General Technical Report United States Forest Pacific Northwest PNW-GTR-679 Department of Service Research Station July 2006 Agriculture The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all pro- grams.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness: You can help W a s h i n g t o n S t a t e P a r k s A necessary prohibition Join us in safeguarding winter recreation: Each year, more and more people are riding snowmobiles • When riding in a new area, obtain a map. into designated Wilderness areas, which is a concern for • Familiarize yourself with Wilderness land managers, the public and many snowmobile groups. boundaries, and don’t cross them. This may be happening for a variety of reasons: many • Carry the message to clubs, groups and friends. snowmobilers may not know where the Wilderness boundaries are or may not realize the area is closed. For more information about snowmobiling opportunities or Wilderness areas, please contact: Wilderness…a special place Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (360) 902-8500 Established by Congress through the Wilderness Washington State Snowmobile Association (800) 784-9772 Act of 1964, “Wilderness” is a special land designation North Cascades National Park (360) 854-7245 within national forests and certain other federal lands. Colville National Forest (509) 684-7000 These areas were designated so that an untouched Gifford Pinchot National Forest (360) 891-5000 area of our wild lands could be maintained in a natural Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (425) 783-6000 state. Also, they were set aside as places where people Mt. Rainier National Park (877) 270-7155 could get away from the sights and sounds of modern Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest (509) 664-9200 civilization and where elements of our cultural history Olympic National Forest (360) 956-2402 could be preserved. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization And

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98503 In Reply Refer To: AUG 1 6 2011 13410-2011-F-0141 13410-2010-F-0175 Daniel M. Mathis, Division Adnlinistrator Federal Highway Administration ATIN: Jeff Horton Evergreen Plaza Building 711 Capitol Way South, Suite 501 Olympia, Washington 98501-1284 Michelle Walker, Chief, Regulatory Branch Seattle District, Corps of Engineers ATIN: Rebecca McAndrew P.O. Box 3755 Seattle, Washington 98124-3755 Dear Mr. Mathis and Ms. Walker: This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the proposed State Route 20, Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization and Chronic Environmental Deficiency Project in Skagit County, Washington, and its effects on the bull trout (Salve linus conjluentus), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), and designated bull trout critical habitat, in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act). Your requests for initiation of formal consultation were received on February 3, 2011, and January 19,2010. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Seattle District (Corps) provided information in support of "may affect, likely to adversely affect" determinations for the bull trout and designated bull trout critical habitat. On April 13 and 14, 2011, the FHWA and Corps gave their consent for addressing potential adverse effects to the bull trout and bull trout critical habitat with a single Opinion. -

'BAPTISM in the HOLY SPIRIT': a Phenomenological and Theological

‘BAPTISM IN THE HOLY SPIRIT’: A Phenomenological and Theological Study By GONTI SIMANULLANG A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Studies Melbourne College of Divinity 2011 Abstract Catholic Charismatic Renewal (CCR) is one of the ecclesial movements recognised in the Catholic Church. Central to CCR (and every branch of Pentecostal Christianity) is a range of experiences commonly denoted as ‘baptism in the Holy Spirit’. Since the emergence of these movements in the mid-1960s it has become common to meet Catholics who claim to have received such an experience, so remarkable for them that it significantly and deeply renewed their lives and faith. In Indonesia, CCR has raised questions among non-CCR Catholics, particularly regarding ‘baptism in the Holy Spirit’, being ‘slain’ or ‘resting’ in the Spirit, and praying in tongues. This study explores, articulates and analyses the meaning of this experience from the perspective of those within Persekutuan Doa Keluarga Katolik Indonesia (PDKKI), that is, the Indonesian Catholic Charismatic Renewal in the Archdiocese of Melbourne. In so doing, it engages this phenomenon from a Roman Catholic theological perspective. The research question for this study is thus: what is the phenomenological and theological meaning of ‘baptism in the Holy Spirit’? A twofold method is employed: within the Whiteheads’ threefold framework for theological reflection – attending, asserting, and pastoral response – Moustakas’ phenomenology is used to analyse interviews with ten volunteer members of PDKKI. The thesis concludes that the essence or meaning of the experience of ‘baptism in the Holy Spirit’ for the participants is an affirmation or a connectedness with the reality of God. -

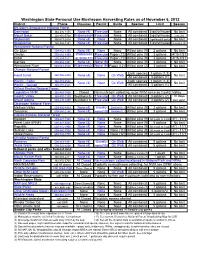

Washington State Personal Use Mushroom Harvesting Rules As of November 6, 2012 District Phone Closures Permit Guide Species Limit Season Mt

Washington State Personal Use Mushroom Harvesting Rules as of November 6, 2012 District Phone Closures Permit Guide Species Limit Season Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Darrington 360-436-1155 None (4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house No limit Mount Baker 360-856-5700 Wilderness(4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house 2 weeks Skykomish 360-677-2414 None (4) None None All combined 1 gal/day&5 gal/yr No limit Snoqualmie 425-888-1421 None (4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house 2 weeks (8) Wenatchee National Forest Cle Elum 509-852-1100 None (4) None None All but pine (9) 2 gallons No limit Chelan 509-682-4900 Wilderness Free use Paper (12) All but pine (9) 3 gallons 4/15-7/31 Entiat 509-784-1511 &LSR(4,11) Free use Paper (12) All but pine (9) 3 gallons 4/15-7/31 Naches 509-653-1401 None (4) None (9) None All but pine (9) 3 gallons No limit Wenatchee River 509-548-2550 Wilderness(4) None (9) Paper (12) All but pine (2) 3 gallons No limit Olympic National Forest Each species 1 gallon (1,3) Hood Canal 360-765-2200 None (4) None On Web No limit All combined 3 gallons (1) Pacific - Forks 360-374-6522 Each species 1 gallon (1,3) None (4) None On Web No limit Pacific - Quinalt 360-288-2525 All combined 3 gallons (1) Gifford Pinchot National Forest Legislative NVM 360-449-7800 Closed No mushroom collecting, outer NVM same as Cowlitz Valley Cowlitz Valley 360-497-1100 SeeMap(4,5) Free use On Web All combined 3 gallons (2) 10 days Mount Adams 509-395-3400 SeeMap(4,5) Free use On Web All combined 3 gallons (2) per year Okanogan -

The Occult Teachings of the Christ According to the Secret Doctrine By: Josephine Ransom

Adyar Pamphlets The Occult Teachings of the Christ... No. 179 The Occult Teachings of the Christ According to the Secret Doctrine by: Josephine Ransom The Blavatsky Lecture, delivered before the Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society in England, 1933 The references are to the original Secret Doctrine by H.P.Blavatsky , published in 1888 Published in 1933 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India “For the teachings of Christ were Occult teachings, which could only be explained at Initiation” [ Secret Doctrine, Volume 2, Page 241] I In presenting my theme I must make it clear that I have drawn solely upon The Secret Doctrine for information. I have not sought elsewhere for corroboration or amplification of any point, save a few quotations from the Bible and have made but few comments myself. I leave it to the students to seek their own answers to the question that must inevitably arise in their minds as the story unfolds. For the sake of a sequence these questions are essential: (1) Who was the Christ? (2) Who was Jesus? [Page 2] (3) What were the Occult Teachings of the Christ? (1) Who was the Christ? The answer comes clearly:“The Logos is Christos.....” (S.D. 1, 241) “......There are three kinds of Light in Occultism .....(1) The Abstract and Absolute Light, which is Darkness; (2) The Light of the Manifested — Unmanifested, called by some the Logos; and (3) The latter Light reflected in the Dhyân Chohans, the minor Logoi — the Elohim, collectively — who, in their turn, shed it on the objective Universe.....” “The Occultists in the East call this Light Daiviprakriti, and in the West the Light of Christos. -

Dungeness River Targeted Watershed Initiative FINAL REPORT

Dungeness River Targeted Watershed Initiative FINAL REPORT For E.P.A. Targeted Watershed Grant WS‐97098101‐0 Prepared By: Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe December 2009 FIGURES Figure 1. Dungeness Watershed on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington. ................................. 4 Figure 2. Dungeness Bay shellfish closure areas. ........................................................................ 6 Figure 3. Phase 1 MST (Ribotyping) sampling locations.............................................................. 9 Figure 4. Phase 2 MST (Bacteroides Target Specific PCR) sampling locations. ......................... 10 Figure 5. Mycoremediation Demonstration Site. ...................................................................... 11 Figure 6. Construction of Mycoremediation Demonstration Site............................................. 12 Figure 7. Schematic of Biofilitration Cells, with native plants and fungi in the Treatment cell and native plants only in the Control. Inflow water is split with equal volumes and fed to the two cells (not to scale). ........................................................ 13 Figure 8. Ground‐breaking excavation at the rain garden site, Helen Haller Elementary School, Sequim, WA.................................................................................................... 15 Figure 9. TWG fresh water monitoring stations and DOH marine monitoring stations. .......... 18 Figure 10. Fecal Coliform Concentration (CFU/100 ml) over 6‐Month Time Period (mean +/‐ standard deviation)................................................................................... -

Delineation of the Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone

Delineation of the Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone River Mouth to Canyon Creek Byron Rot Pam Edens Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe October 1, 2008 Acknowledgements This report was greatly improved from comments given by Patricia Olson, Department of Ecology, Tim Abbe, Entrix Corp, Joel Freudenthal, Yakima County Public Works, Bob Martin, Clallam County Emergency Services, and Randy Johnson, Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe. This project was not directly funded as a specific grant, but as one of many tribal tasks through the federal Pacific Coastal Salmon fund. We thank the federal government for their support of salmon recovery. Cover: Roof of house from Kinkade Island in January 2002 flood (Reach 6), large CMZ between Hwy 101 and RR Bridge (Reach 4, April 2007), and Dungeness River Channel Migration Zone map, Reach 6. ii Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………….1 Legal requirement for CMZ’s……………………………………….1 Terminology used in this report……………………………………..2 Geologic setting…………………………………………………......4 Dungeness flooding history…………………………………………5 Data sources………………………………………………………....6 Sources of error and report limitations……………………………...7 Geomorphic reach delineation………………………………………8 CMZ delineation methods and results………………………………8 CMZ description by geomorphic reach…………………………….12 Conclusion………………………………………………………….18 Literature cited……………………………………………………...19 iii Introduction The Dungeness River flows north 30 miles and drops 3800 feet from the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The upper watershed south of river mile (RM) 10 lies entirely within private and state timberlands, federal national forests, and the Olympic National Park. Development is concentrated along the lower 10 miles, where the river flows through relatively steep (i.e. gradients up to 1%), glacial and glaciomarine deposits (Drost 1983, BOR 2002). -

Public Law 94-527 94Th Congress an Act to Amend the National Trails System Act (82 Stat

PUBLIC LAW 94-527—OCT. 17, 1976 90 STAT. 2481 Public Law 94-527 94th Congress An Act To amend the National Trails System Act (82 Stat. 919), and for other purposes. Oct. 17, 1976 [S. 2112] Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the National National scenic Trails System Act (82 Stat. 919; 16 U.S.C. 1241 et seq.) is amended trails, as follows: In section 5(c), add the following new paragraphs; 16 USC 1244. "(15) Bartram Trail, extending through the States of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mis sissippi, and Tennessee. "(16) Daniel Boone Trail, extending from the vicinity of States- ville. North Carolina, to Fort Boonesborough State Park, Kentucky. "(17) Desert Trail, extending from the Canadian border through parts of Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, California, and Ari zona, to the Mexican border. "(18) Dominguez-Escalante Trail, extending approximately two thousand miles along the route of the 1776 expedition led by Father Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Father Silvestre Velez de Escalante, originating in Santa Fe, New Mexico; proceeding north west along the San Juan, Dolores, Gunnison, and White Rivers in Colorado; thence westerly to Utah Lake; thence southward to Arizona and returning to Santa Fe. "(19) Florida Trail, extending north from Everglades National Park, including the Big Cypress Swamp, the Kissimme Prairie, the Withlacoochee State Forest, Ocala National Forest, Osceola National Forest, and Black Water River State Forest, said completed trail to be approximately one thousand three hundred miles long, of which over four hundred miles of trail have already been built. -

Land and Resource Management Plan

United States Department of Land and Resource Agriculture Forest Service Management Plan Pacific Northwest Region 1990 Olympic National Forest I,,; ;\'0:/' "\l . -'. \.. \:~JK~~'.,;"> .. ,. :~i;/i- t~:.(~#;~.. ,':!.\ ," "'~.' , .~, " ,.. LAND AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN for the OLYMPIC NATIONAL FOREST PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION PREFACE Preparation of a Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan) for the Olympic National Forest is required by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA) as amended by the National Forest Management Act (NFMA). Regulations developed under the RPA establish a process for developing, adopting, and revising land and resource Plans for the National Forest System (36 CFR 219). The Plan has also been developed in accordance with regulations (40 CFR 1500) for implementing the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). Because this Plan is considered a major Federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment, a detailed statement (environmental impact statement) has been prepared as required by NEPA. The Forest Plan represents the implementation of the Preferred Alternative as identified in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Forest Plan. If any particular provision of this Forest Plan, or application of the action to any person or circumstances is found to be invalid, the remainder of this Forest Plan and the application of that provision to other persons or circumstances shall not be affected. Information concerning this plan can be obtained