The Food Copyright © 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lunch Menu to Go

Lunch Menu Soups and Salads †… RED BORSCHT – hearty vegetables, little sweet and little sour, sour cream . cup 5 bowl 8 CHICKEN PAPRIKASH . cup 6 bowl 10 LOBSTER AND CRAB BISQUE – chunky and velvety, with a kick . cup 7 bowl 12 SOUP FLIGHT $9 SOUP OF THE DAY . MP ´… HOUSE SALAD – mixed greens, grape tomatoes, carrots, red onions . 6 †… GREEK SALAD – greens, cucumbers, grape tomatoes, red onions, olives, feta, balsamic-basil . 8 †… ROASTED BEET – arugula, orange fillets, honey goat cheese, honey-pomegranate dressing . 10 †… CAPRESE SALAD – tomatoes, fresh mozzarella, arugula, basil, pesto, balsamic . 10 †… SPINACH AND STRAWBERRY – honey goat cheese, candied walnuts, raspberry vinaigrette . 11 … WEDGE – grape tomatoes,red onion,Bleu cheese,crispy bacon, deviled egg, Parmesan . 11 peppercorn dressing ´… GRILLED VEGETABLE SALAD – spinach, grilled zucchini, asparagus, red onions, parmesan, . 12 balsamic ´… WARM MUSHROOM AND ASPARAGUS SALAD – red onions, glazed walnuts, mixed greens, . 12 raspberry vinaigrette + add to any salad chicken $7, 8 oz salmon $12, U-10 scallops $15, shrimp $10 Appetizers †… DEVILED EGGS – creamy Dijon dill and tangy sweet pickle filling, paprika . 8 FRIED LIME-CHILL SHISHITO PEPPERS – perfect snack to share . 8 BUFFALO FRIED CAULIFLOWER FLORETS – peppercorn-ranch drizzle . 9 STUFFED HUNGARIAN PEPPERS – sausage, onions, carrots, rice, tomato sauce, Parmesan . 12 ´ ROASTED VEGGIE HUMMUS – pita, cucumbers,warm olives . 10 SNACKING PLATTER – chef's creation, grilled veggies, salads, olives, grilled pita . 15 † CHEESE PLEASE – nuts, fruit, jam, crackers . 15 CHARCUTERIE BOARD – imported smoked and cured meats, cheeses, pickled veggies, crostini . 22 CRAB CAKES – panko crusted, pan fried, garlic remoulade, red slaw . 15 CHICKEN KOPITA – feta, spinach, peppers onions, wrapped in filo, ouzo cream sauce . -

Catering Menu BREAKFAST BREAKFAST

PENNSYLVANIA CONVENTION CENTER Catering Menu BREAKFAST BREAKFAST Continental All breakfasts include freshly brewed coffee, decaf, hot tea and fruit juice. Orders with less than 15 guests will be subject to a $200 service fee. All services are provided on a high grade disposable ware. Rise and Shine Morning Glory Fresh Baked Bagels with Cream Cheese, House Made Muffins and Fresh Baked Scones Butter and Jellies with Yorkshire Cream $13.00 $17. 25 Morning Dew Ben Franklin Starter Fresh Sliced Fruit, Honey Yogurt Dip and Kind Bars Fresh Sliced Fruit, Breakfast Breads and $14.00 Fresh Baked Bagels with Cream Cheese, Broad Street Butter and Jellies Whole Fruit, Breakfast Breads and $23.00 Chef Selected Danish Jump Start $15.00 Fresh Baked Bagels with Cream Cheese, Daybreak Butter and Jellies, House Made Mini Muffins, Assorted Donuts and House Made Muffins Chef Selected Danish, Whole Fruit and Kind Bars $15.00 $23.25 Hot Buffet All breakfasts include freshly brewed coffee, decaf, hot tea and fruit juice. Orders with less than 15 guests will be subject to a $200 service fee. All services are provided on a high grade disposable ware. The Terminal $30.00 Scrambled Eggs, Apple Wood Smoked Bacon, Pork Sausage Links, Home Fried Potatoes, Sliced Seasonal Fruit, Fresh Baked Bagels with Cream Cheese, Butter and Jellies, and House Made Muffins * Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. Prices subject to additional fees and taxes. PENNSYLVANIA CONVENTION CENTER CATERING MENU 3 BREAKFAST Buffet Enhancements Enhancements require a minimum of 15 guests. -

Festiwal Chlebów Świata, 21-23. Marca 2014 Roku

FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA, 21-23. MARCA 2014 ROKU Stowarzyszenie Polskich Mediów, Warszawska Izba Turystyki wraz z Zespołem Szkół nr 11 im. Władysława Grabskiego w Warszawie realizuje projekt FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA 21 - 23 marca 2014 r. Celem tej inicjatywy jest promocja chleba, pokazania jego powszechności, ale i równocześnie różnorodności. Zaplanowaliśmy, że będzie się ona składała się z dwóch segmentów: pierwszy to prezentacja wypieków pieczywa według receptur kultywowanych w różnych częściach świata, drugi to ekspozycja producentów pieczywa oraz związanych z piekarnictwem produktów. Do udziału w żywej prezentacji chlebów świata zaprosiliśmy: Casa Artusi (Dom Ojca Kuchni Włoskiej) z prezentacją piady, producenci pity, macy oraz opłatka wigilijnego, Muzeum Żywego Piernika w Toruniu, Muzeum Rolnictwa w Ciechanowcu z wypiekiem chleba na zakwasie, przedstawiciele ambasad ze wszystkich kontynentów z pokazem własnej tradycji wypieku chleba. Dodatkowym atutem będzie prezentacja chleba astronautów wraz osobistym świadectwem Polskiego Kosmonauty Mirosława Hermaszewskiego. Nie zabraknie też pokazu rodzajów ziarna oraz mąki. Realizacją projektu będzie bezprecedensowa ekspozycja chlebów świata, pozwalająca poznać nie tylko dzieje chleba, ale też wszelkie jego odmiany występujące w różnych regionach świata. Taka prezentacja to podkreślenie uniwersalnego charakteru chleba jako pożywienia, który w znanej czy nieznanej nam dotychczas innej formie można znaleźć w każdym zakątku kuli ziemskiej zamieszkałym przez ludzi. Odkąd istnieje pismo, wzmiankowano na temat chleba, toteż, dodatkowo, jego kultowa i kulturowo – symboliczna wartość jest nie do przecenienia. Inauguracja FESTIWALU CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA planowana jest w piątek, w dniu 21 marca 2014 roku, pierwszym dniu wiosny a potrwa ona do niedzieli tj. do 23.03. 2014 r.. Uczniowie wówczas szukają pomysłów na nieodbywanie typowych zajęć lekcyjnych. My proponujemy bardzo celowe „vagari”- zapraszając uczniów wszystkich typów i poziomów szkoły z opiekunami do spotkania się na Festiwalu. -

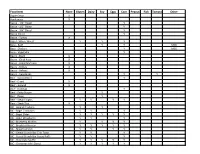

Quick Reference Allergy List

Food Item None Gluten Dairy Soy Eggs Corn Peanut Fish Tomato Other Apple Crisps X Applesauce X Bacon - 1/4" Diced Y Bacon - 1/2" Diced Y Bacon - 3/4" Diced Y Bacon Sliced Y Bacon - Turkey X Bagel - Whole Wheat Y Y Y Base - Beef Y Y MSG Base - Chicken Y MSG Base - Vegetable Y Beans - Black X Beans - Chick Peas X Beans - Great Northern X Beans - Kidney X Beans - Refried X Beans - Vegetarian Y Y Beef - Corned Beef Y Beef - Diced X Beef - Ground X Beef - Hot Dog Y Beef - Patty Burger Y Beef - Roast Y Beef - Steak Fingers Y Y Y Y Beef - Steak Tips X BIC - Animal Crackers Y Y BIC - Bagel Cinnamon Y Y Y BIC - Bagel Slider Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Bagel Strawberry Y Y Y BIC - Blueberry Muffins Y Y Y Y BIC - Breakfast Burrito Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Breakfast Stick Y Y Y Y BIC - Cereal Crunch Bar Cinn Toast Y Y Y BIC - Cereal Crunch Bar Cocoa Puffs Y Y Y BIC - Chocolate Muffin Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Cinnamon Mini Donut Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Early Risers Y Y Y Y BIC - French Toast Sticks Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Pancake in a Bag Y Y Y Y BIC - Pancake on a Stick Y Y Y Y Y BIC - Sausage Bites in a Bag Y Y Y Y BIC - Scooby Snacks Y Y Y BIC - Waffle Bites in a Bag Y Y Y Y Y Bread - Biscuit Y Y Y Bread - Dinner Roll Y Y Bread - English Muffin Y Y MC Y Bread - French Loaf Y Y Y Y Bread - Garlic Toast Y Y Y Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Dinner Roll Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Hamburger Bun Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Hot Dog Bun Y Y Bread - Gluten Free Sandwich Loaf Y Y Bread - Hamburger Bun Y Y Bread - Hoagie Large Y Y Bread - Hoagie Slider Y Y Bread - Hot Dog Bun Y Y Bread - Pita Round Y Y Y Bread - Sandwich/Loaf -

Rustic Acres Farm SERVICE & PRICING GUIDE CONTENTS

Rustic Acres Farm SERVICE & PRICING GUIDE CONTENTS BE OUR GUEST /01 ABOUT JPC History & Philosophy /02 Amenities & Pricing /04 Ceremonies /05 Farm FAQs /06 CATERING So Much More Than Food /08 MENU Your Choice /11 Savory Family Style /13 Southern BBQ Family Style /17 Elegant Plated Sit Down /20 Chef Stations /25 Appetizer Enhancements /29 Sweet Endings /33 Bar Mixers & Beverage Services /38 CONNECT /40 / BE OUR GUEST BE OUR GUEST A rippling creek, rolling fields of pumpkins and sunflowers, grazing horses, expansive views and wind across the pond… This is Rustic Acres Farm. Founded in April 2011, Rustic Acres is located in the sprawling hills of rural Western Pennsylvania along Route 19 between the quaint village of Volant, and the bustling Grove City Outlet mall. From the majestic and iconic weeping willow, to sweeping pastoral views, a vast array of locations for a stunning wedding day ceremony and celebration exist within the acres of the farm. Managed by the award winning JPC EVENT GROUP, Rustic Acres Farm offers outdoor beauty, fine catering packages in a range of styles and tastes, inclusive equipment, and venue coordination that ensures a stress-free and memorable day for you and your guests. Come & experience life celebrated / 01 JPC HISTORY & PHILOSOPHY / ABOUT JPC HISTORY WE BRING YOUR VISION TO LIFE WITH EFFORTLESS ELEGANCE AND SEAMLESS PLANNING, IN SIGNATURE STYLE. Real people. real design. real food. / 02 ABOUT JPC Our history For over 23 years, we have followed our passion by creating memories for our clients that last a lifetime. We have always believed that quality is more impactful than quantity, and we strive to create events that engage all of your senses with a commitment to sustainability and quality local and seasonal ingredients often grown on our own JPC Willowbrook Farm. -

Big, Bold, BBQ

Big, Bold, BBQ Schiff’s Food Service reserves the right to limit quantities & correct typographical errors. Promotional prices & allowances valid from 7.16.18 - 8.31.18 Sweet Tea Ribs Meat Room Packer Pork BB Ribs 2 lb & Up FF IBP (#720207, 18/2 lb avg)...$.10 off/lb SFS Chicken Shells Cut to Spec (#710028, 22/2.75-3 lb)...$.10 off/lb Packer Beef Brisket CH CV (#730415, 5/11 lb avg)...$.10 off/lb *Recipe adapted from the Food Network Packer Pork Butts Boneless Ingredients 6 bags black tea (#222351) (#720357, 4/2-8 lb avg)...$.10 off/lb 1/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons packed light brown sugar (#226132) Packer Beef Flank Steak CH CV Kosher salt (#264715) and freshly ground (#730420, 8/9-11 lb avg)...$.10 off/lb pepper (#264305) 1 orange (#500636) 2 racks baby back ribs (#720207) 1 lemon (#500591) Directions Empty 3 tea bags into a bowl and combine the loose tea with 1/4 cup brown sugar, 2 Pulled Pork Vinegar Base teaspoons salt and 1/4 teaspoon pepper. (#310044, 2/5 lb)...$.50 off/cs Grate in the orange zest. Pat the ribs dry and trim the membrane from the underside. Precooked Sausage Griller Hot 5 1/2” Rub the tea mixture over the ribs; place in a (#332208, 1/10 lb)...$.50 off/cs roasting pan, meat-side up, and bring to room temperature, about 20 minutes. Precooked Sausage Griller Sweet 5 1/2” Preheat the oven to 275° F. Steep the (#332209, 1/10 lb)...$.50 off/cs remaining 3 tea bags in 2 cups boiling water, about 5 minutes. -

Jw Marriott Parq Vancouver

EVENT MENU JW MARRIOTT PARQ VANCOUVER 39 Smithe Street, Vancouver V6B 0R3 Canada +1 604-676-0888 TABLE OF CONTENTS EVENTS BY JW MEETINGS IMAGINED p. 3 PLATED BREAKFAST p. 4 JW Marriott sets the stage for BREAKFAST BUFFET p. 5-9 exceptional events, leading with our BREAKFAST ENHANCEMENTS p. 10 culinary expertise. Our team brings the SWEET AND SAVOURY BREAKS p. 11-13 art of food to life through demonstrations and storytelling, A LA CARTE COFFEE BREAK p. 14 infusing our menus with local flavor and PLATED LUNCH p. 15-17 personality. Every JW event is BUFFET LUNCH p. 18-23 thoughtfully designed to enhance the BOXED LUNCH p. 24 planner and attendee experience, showcasing our culinary talent with live RECEPTION p. 25-26 cooking and interactive moments PLATED DINNER p. 27-31 throughout the meeting experience. We BUFFET DINNER p. 32-36 are proud to offer fresh and crafted BUFFET DINNER ENHANCEMENTS p. 37-38 culinary creations that are unique and memorable. CUSTOM DINNER PACKAGE p. 39-45 BEVERAGE MENU p. 46-47 WINE LIST & BAR PACKAGES p. 48-49 EVENT SERVICES p. 50 GENERAL INFORMATION p. 51-52 2 MEETINGS IMAGINED EVERY MEETING HAS A PURPOSE. FIND YOURS TO CREATE A MORE IMPACTFUL AND INSPIRED MEETING. When the objective is to commemorate a milestone or accomplishment. CELEBRATE Showcase exceptional food and wine pairings that encourage your guests to indulge and leave them with lasting memories of the event. When the objective is to engage in a meaningful dialogue to reach a decision. DECIDE Select simple and light options that place focus on the discussion and do not distract. -

Fall and Winter Menu Offerings

A Main Event Caterers Fall + Winter Menu Offerings Blood Orange Sparkler Seasonal Specialty Cocktails blood orange juice + champagne Paper Plane Cocktail amaro, Aperol + bourbon Cranberry Spice Champagne fresh lemon juice muddled cranberries + agave nectar bubbly champagne + winter spices Moscow Mule ice cold vodka The French 75 fresh lime juice + spicy ginger beer champagne + smooth gin lime wheel garnish lemon juice + simple syrup offered in flutes with a lemon twist Cranberry Aperol Spritz tart cranberry juice + Aperol Apple Grove Champagne topped with prosecco apple liqueur + champagne apple slice for garnish Mezcal Old Fashioned smokey mezcal Classic Old Fashioned Angostura bitters muddled bitters, maraschino cherry + orange orange peel a generous helping of bourbon splash of club soda Autumn Delight bourbon + apple cider Good Tidings cinnamon scented syrup vodka + orange liqueur fresh apple slice garnish served over rocks lemon + cranberry juice allspice dram Ginger Pear Cocktail bourbon + lemon juice Lychee Martini pear nectar + honey-ginger simple syrup lychee juice + vodka sugar rimmed glass splash of ginger ale The Big Apple The Perfect Manhattan whiskey, sweet vermouth + dash of bitters a 'perfect' blend of bourbon, sweet + dry vermouth sparkling apple cider with a cherry on top! garnished with petite lady apple 2 Tray Passed Hors d’Oeuvres Lobster Roll butter poached lobster griddled bun fresh chives Beet Cured Salmon house made ‘everything’ cracker Wild Mushroom Mousse pickled cucumber polenta toast dill sour cream crispy -

First & Share Entrée Salad

299 MARIN BLVD | LATE SPRING/EARLY SUMMER 2018 | DOWNTOWN JC FIRST & SHARE MARKET SOUP HANDMADE BURRATA herb toast, vegetarian, always 8 arugula, pesto, grape tomatoes, toast 14 SEARED WILD YELLOW FIN TUNA LEMON GARLIC OCTOPUS avocado, pico de gallo, roasted corn spicy chickpea purée, arugula, olives micro greens, warm flatbread 16 tomato, onion 16 HUMMUS CHEESE PLATE & DAN’S HOMEMADE JAM Kalamata olives, smoked paprika grainy mustard, cornichon, ciabatta toast 17 pomegranate molasses, carrots, naan 12 add imported prosciutto 21 SPANISH MUSSELS CORNMEAL-FRIED GREEN TOMATO STACK chorizo, tomato, seasonal ale, baguette 15 SEARED SEA SCALLOPS FRENCH MUSSELS zippy Cajun remoulade, spring pea shoots bleu cheese, Dijon, cream, baguette 15 chive oil drizzle 17 CAST IRON TRUFFLED MAC & CHEESE CRISPY CALAMARI Upstate NY cheddar, manchego, gruyere spicy roasted tomato-serrano sauce 14 smoked gouda, roasted cauliflower crispy panko top 14 ENTRÉE SALAD ASIAN CHICKEN SALAD greens, cabbage, scallion, almonds, sesame seeds, cilantro, crispy wonton, rice noodles sesame-ginger dressing 18 GRILLED SALMON, GRAINS & GREENS quinoa, bulgur, farro, arugula, pistachio, avocado, tomato, orange-basil vinaigrette 26 without salmon 16 ROAST ORGANIC CHICKEN BREAST BABY KALE CAESAR shaved ricotta salata, pumpernickel croutons, imported Parmesan, garlic-lemon dressing 18 GET YOUR GREEK ON (WITH SHRIMP!) warm flat bread, green leaf, kale, tomato, feta, cukes, Kalamata olives, pickled onions traditional garlic-lemon dressing 22 Parties of 5 or more guests, we will add -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY NOON: Macaroni & Cheese, Seasoned NOON: Fisherman’s Platter served with NOON: Swiss Steak with Tomatoes, Peppers Greens, Stewed Tomatoes, Jalapeno 1 Golden Fries, Cocktail Sauce & Tartar Sauce,2 & Onions, served over Rice, Baby Butterbeans, 3 Cornbread, Blackberry Cobbler Slaw, Hushpuppy, Lemon Cre’me Crepe Spoon Roll, Chocolate Glazed-Peanut Butter Additional Selections: Brats Medallions Additional Selections: Kentucky Hot Brown Cookie with Sauerkraut, Macaroni & Cheese, Roll topped with Creamy Mornay Sauce, Spicy Slaw Additional Selections: Toasted Ravoli with EVENING: Sliced Honey Ham, Lettuce & Marinara Dipping Sauce, Three Bean Salad, EVENING: Hearty Pioneer Beef Stew, Crunchy Tomato on Potato Bun, Pickle Spear, Broccoli Grilled Texas Toast H EALTHC ARE Fried Okra, Biscuit, Frosted Cupcake Cheddar Soup served with Crackers, Sweet EVENING: Personal Pan Pizza, Pickled Pepperoncini, Tossed Salad, served with Choice Additional Selections: Stuffed Baked Potato Stuffed Pears of Dressings, Malibu Fruit Salad MAULDIN served with All the Trimmings, Parmesan Bread Additional Selections: Smothered Liver & Additional Selections: Beef Pot Pie, with Stick Onions, Whipped Potatoes w/Gravy, Mixed Golden Crust, Tossed Salad served with Choice Vegetables, Roll of Dressings, Wheat Roll NOON: Roasted Turkey served with Gravy NOON: Spaghetti with Italian Meat Sauce, NOON: Alice Springs Chicken served over NOON: Baked Ham, Pineapple Bake, NOON: Vegetable Plate: Macaroni & NOON: Golden Fried Fish -

Starters Salad Sandwich Mains Dessert

STARTERS MAINS TUNA Yellow fin, raw, thinly sliced, à la Niçoise, 110 MAHI-MAHI pan seared, tomato vinaigrette, potato pureé, watercress 130 HAMACHI raw, thinly sliced, soy & Saké marinated, yoghurt 110 FISH & CHIPS cobia, remoulade, watercress 130 SALMON cured, thinly sliced, dill, sour cream, Jalapeño salsa 125 DAILY CATCH for 2, whole fish, urap, sambal, kemangi, coconut rice 215 BEEF carpaccio, parmesan, rucola 110 DUCK LEG confit, rosemary potatoes, jus 130 PRAWN cocktail, lettuce, tomato, toast 95 PORK RIBS soy glaze, coleslaw, coconut rice 140 TERRINE salmon, slipper lobster, scallops 100 STEAK grilled, mushroom sauce, fries, green salad 160 - add 40 for 3 course COUNTRY PATÉ pickles, chutney, country bread 95 menu PARFAIT chicken liver, shallot marmalade, baguette 100 BOLOGNESE linguini, Parmesan, herbs 110 SERRANO HAM ‘Gran Reserve’, honey melon, rucola 110 PRAWN linguini, cream, chili oil, sauteéd greens 110 GAZPACHO cucumber, watermelon, crostini, Serrano ham, chili jam 95 RAVIOLI green pea, beurre blanc, watercress 110 QUICHE mushrooms, onion, leek, Rucola salad, feta 75 SOTO AYAM chicken soup, coconut rice, traditional garnish 100 PHO Vietnamese style pork broth, pasta, pork cheeks, prawns 100 SALAD SATÉ beef and lamb, krupuk, acar, saté sauce, rice 120 BAKMIE egg noodle, duck leg, sprouts, cabbage, lemon basil, chili 110 BEETROOT (V) apple, feta, caramel, walnuts 110 NASI LEMAK beef rendang, salted fish, acar, egg, sambal, coconut rice 120 NIÇOISE tuna confit, cured halfbeak, potato , egg, olives 110 CHICKEN traditional -

TSP Forum Cookbook 1

TSP Forum Cookbook 1 TSP Forum Cookbook TSP Forum Cookbook 2 TSP Forum Cookbook © 2011 by The Survival Podcast Forum and published under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ The Survival Podcast Forum http://thesurvivalpodcast.com/forum 3 TSP Forum Cookbook Contents Preface …..................................................................................................................................... 5 Appetizers ….............................................................................................................................. 6 Beverages …................................................................................................................................ 9 Breads …..................................................................................................................................... 13 Breakfast Foods ….................................................................................................................... 41 Brewing Wines, Beer, Sodas and Cyder …............................................................................ 53 Casseroles ….............................................................................................................................. 63 Cast Iron and Campout Cooking …...................................................................................... 76 Condiments, Sauces, Dips and Flavorings …....................................................................... 81 Crockpot Recipes …................................................................................................................