Prisons and Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Fireworks, Chinese New Year and the COVID-19 Lockdown on Air Pollution and Public Attitudes

Special Issue on COVID-19 Aerosol Drivers, Impacts and Mitigation (VII) Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 20: 2318–2331, 2020 ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online Publisher: Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2020.06.0299 Effect of Fireworks, Chinese New Year and the COVID-19 Lockdown on Air Pollution and Public Attitudes Peter Brimblecombe1,2, Yonghang Lai3* 1 Department of Marine Environment and Engineering, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan 2 Aerosol Science Research Center, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan 3 School of Energy and Environment, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong ABSTRACT Concentrations of primary air pollutants are driven by emissions and weather patterns, which control their production and dispersion. The early months of the year see the celebratory use of fireworks, a week-long public holiday in China, but in 2020 overlapped in Hubei Province with lockdowns, some of > 70 days duration. The urban lockdowns enforced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic give a chance to explore the effect of rapid changes in societal activities on air pollution, with a public willing to leave views on social media and show a continuing concern about the return of pollution problems after COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. Fireworks typically give rise to sharp peaks in PM2.5 concentrations, though the magnitude of these peaks in both Wuhan and Beijing has decreased under tighter regulation in recent years, along with general reductions in pollutant emissions. Firework smoke is now most evident in smaller outlying cities and towns. The holiday effect, a reduction in pollutant concentrations when normal work activities are curtailed, is only apparent for NO2 in the holiday week in Wuhan (2015–2020), but not Beijing. -

Solitary Confinement of Teens in Adult Prisons

Children in Lockdown: Solitary Confinement of Teens in Adult Prisons January 30, 2010 By Jean Casella and James Ridgeway 23 Comments While there are no concrete numbers, it’s safe to say that hundreds, if not thousands of children are in solitary confinement in the United States–some in juvenile detention facilities, and some in adult prisons. Short bouts of solitary confinement are even viewed as a legitimate form of punishment in some American schools. In this first post on the subject, we address teenagers in solitary confinement in adult prisons. In large part, this grim reality is simply a symptom of the American criminal justice system’s taste for treating children as adults. A study by Michele Deitch and a team of student researchers at the University of Texas’s LBJ School found that on a given day in 2008, there were more than 11,300 children under 18 being held in the nation’s adult prisons and jail. According to Deitch’s 2009 report From Time Out to Hard Time, ”More than half the states permit children under age 12 to be treated as adults for criminal justice purposes. In 22 states plus the District of Columbia, children as young as 7 can be prosecuted and tried in adult court, where they would be subjected to harsh adult sanctions, including long prison terms, mandatory sentences, and placement in adult prison.” These practices set the United States apart from nearly all nations in both the developed and the developing world. Documentation on children placed in solitary confinement in adult prisons is spotty. -

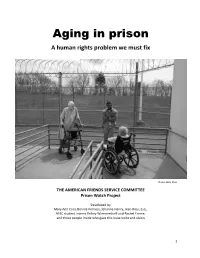

Aging in Prison a Human Rights Problem We Must Fix

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 3 2. Testimonials 6 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 11 4. Acknowledgements 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three- strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-without-parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. -

Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape A Dissertation Presented by Jane Clare Jones to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University December 2016 Copyright by Jane Clare Jones 2016 ii Stony Brook University The Graduate School Jane Clare Jones We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dissertation Advisor – Dr. Edward S Casey Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy Chairperson of Defense – Dr. Megan Craig Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy Internal Reader – Dr. Eva Kittay Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy External Reader – Dr. Fiona Vera-Gray Durham Law School, Durham University, UK This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of the Dissertation Sovereign Invulnerability: Sexual Politics and the Ontology of Rape by Jane Clare Jones Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Stony Brook University 2016 As Rebecca Whisnant has noted, notions of “national…and…bodily (especially sexual) sovereignty are routinely merged in -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

Respondus Lockdown Browser & Monitor Remote Proctoring Is Available, but Not Recommended. Please Consider Alternative Assess

Respondus Lockdown Browser & Monitor Remote proctoring is available, but not recommended. Please consider alternative assessment strategies. If you absolutely cannot use alternatives, and want to move forward using Respondus Lockdown Browser, here are some aspects to consider to minimize the impact to your students: Definitions: • Respondus Lockdown Browser is an internet browser downloaded and installed by students, which locks down the computer on which they are taking the test so that students cannot open other applications or web pages. Lockdown Browser does not monitor or record student activity. • Respondus Monitor is an instructor-enabled feature of Respondus Lockdown Browser, which uses the students’ webcams to record video and audio of the exam environment. It also records the students’ computer screens. Instructors can view these recordings after the exam session is over. Considerations: • If Respondus Monitor is enabled, students must have a webcam to take the test. Be aware that many of your students may not have access to a webcam. You will need to offer an alternative assessment for students who do not have a webcam. o Students may not be asked to purchase a webcam for these exams, unless one was required as an initial expectation for the course. Requiring the purchase of additional materials not specified in the class description or original syllabus opens up a host of concerns, including but not limited to: student financial aid and ability to pay, grade appeals, and departmental policies. • Both Respondus Lockdown Browser and Respondus Monitor require a Windows or Mac computer. iPads require a specialized app, and are not recommended. -

Unmet Promises: Continued Violence and Neglect in California's Division

UNMET PROMISES Continued Violence & Neglect in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice Maureen Washburn | Renee Menart | February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 7 History 9 Youth Population 10 A. Increased spending amid a shrinking system 10 B. Transitional age population 12 C. Disparate confinement of youth of color 13 D. Geographic disparities 13 E. Youth offenses vary 13 F. Large facilities and overcrowded living units 15 Facility Operations 16 A. Aging facilities in remote areas 16 B. Prison-like conditions 18 C. Youth lack safety and privacy in living spaces 19 D. Poorly-maintained structures 20 Staffing 21 A. Emphasis on corrections experience 21 B. Training focuses on security over treatment 22 C. Staffing levels on living units risk violence 23 D. Staff shortages and transitions 24 E. Lack of staff collaboration 25 Violence 26 A. Increasing violence 26 B. Gang influence and segregation 32 C. Extended isolation 33 D. Prevalence of contraband 35 E. Lack of privacy and vulnerability to sexual abuse 36 F. Staff abuse and misconduct 38 G. Code of silence among staff and youth 42 H. Deficiencies in the behavior management system 43 Intake & Unit Assignment 46 A. Danger during intake 46 B. Medical discontinuity during intake 47 C. Flaws in assessment and case planning 47 D. Segregation during facility assignment 48 E. Arbitrary unit assignment 49 Medical Care & Mental Health 51 A. Injuries to youth 51 B. Barriers to receiving medical attention 53 C. Gender-responsive health care 54 D. Increase in suicide attempts 55 E. Mental health care focuses on acute needs 55 Programming 59 A. -

Hospital Lockdown Guidance

Hospital Lockdown: A Framework for NHSScotland Strategic Guidance for NHSScotland June 2010 Hospital Lockdown: A Framework for NHSScotland Strategic Guidance for NHSScotland Contents Page 1. Introduction..........................................................................................5 2. Best Practice and relevant Legislation and Regulation ...................7 2.1 Best Practice............................................................................7 2.8 Relevant legislation and regulation ..........................................8 3. Lockdown Definition ..........................................................................9 3.1 Definition of site/building lockdown...........................................9 3.4 Partial lockdown .......................................................................9 3.5 Portable lockdown ..................................................................10 3.6 Progressive/incremental lockdown .........................................10 3.8 Full lockdown..........................................................................11 4. Developing a lockdown profile.........................................................12 4.3 Needs Analysis ......................................................................13 4.4 Critical asset profile................................................................14 4.9 Risk Management ..................................................................14 4.10 Threat and hazard assessment..............................................14 4.13 Lockdown threat -

The Effect of Lockdown Policies on International Trade Evidence from Kenya

The effect of lockdown policies on international trade Evidence from Kenya Addisu A. Lashitew Majune K. Socrates GLOBAL WORKING PAPER #148 DECEMBER 2020 The Effect of Lockdown Policies on International Trade: Evidence from Kenya Majune K. Socrates∗ Addisu A. Lashitew†‡ January 20, 2021 Abstract This study analyzes how Kenya’s import and export trade was affected by lockdown policies during the COVID-19 outbreak. Analysis is conducted using a weekly series of product-by-country data for the one-year period from July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020. Analysis using an event study design shows that the introduction of lockdown measures by trading partners led to a modest increase of exports and a comparatively larger decline of imports. The decline in imports was caused by disruption of sea cargo trade with countries that introduced lockdown measures, which more than compensated for a significant rise in air cargo imports. Difference-in-differences results within the event study framework reveal that food exports and imports increased, while the effect of the lockdown on medical goods was less clear-cut. Overall, we find that the strength of lockdown policies had an asymmetric effect between import and export trade. Keywords: COVID-19; Lockdown; Social Distancing; Imports; Exports; Kenya JEL Codes: F10, F14, L10 ∗School of Economics, University of Nairobi, Kenya. Email: [email protected] †Brookings Institution, 1775 Mass Av., Washington DC, 20036, USA. Email: [email protected] ‡The authors would like to thank Matthew Collin of Brookings Institution for his valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript. 1 Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic has spawned an unprecedented level of social and economic crisis worldwide. -

Fight, Flight Or Lockdown Edited

Fight, Flight or Lockdown: Dorn & Satterly 1 Fight, Flight or Lockdown - Teaching Students and Staff to Attack Active Shooters could Result in Decreased Casualties or Needless Deaths By Michael S. Dorn and Stephen Satterly, Jr., Safe Havens International. Since the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007, there has been considerable interest in an alternative approach to the traditional lockdown for campus shooting situations. These efforts have focused on incidents defined by the United States Department of Education and the United States Secret Service as targeted acts of violence which are also commonly referred to as active shooter situations. This interest has been driven by a variety of factors including: • Incidents where victims were trapped by an active shooter • A lack of lockable doors for many classrooms in institutions of higher learning. • The successful use of distraction techniques by law enforcement and military tactical personnel. • A desire to see if improvements can be made on established approaches. • Learning spaces in many campus buildings that do not offer suitable lockable areas for the number of students and staff normally in the area. We think that the discussion of this topic and these challenges is generally a healthy one. New approaches that involve students and staff being trained to attack active shooters have been developed and have been taught in grades ranging from kindergarten to post secondary level. There are however, concerns about these approaches that have not, thus far, been satisfactorily addressed resulting in a hot debate about these concepts. We feel that caution and further development of these concepts is prudent. Developing trend in active shooter response training The relatively new trend in the area of planning and training for active shooter response for K-20 schools has been implemented in schools. -

Crown's Newsletter

VOLUME TEN CROWN’S DECEMBER 2019 NEWSLETTER 2019 CanLIIDocs 3798 THE UNREPRESENTED ACCUSED: Craig A. Brannagan 3 UNDERSTANDING EXPLOITATION: Veronica Puls & Paul A. Renwick 15 THE NEW STATUTORY READBACK: Davin M. Garg 22 A HANDFUL OF BULLETS: Vincent Paris 26 SECONDARY SOURCE REVIEW: David Boulet 37 TRITE BITES FIREARM BAIL HEARINGS: Simon Heeney & Tanya Kranjc 65 REVOKING SUSPENDED SENTENCES: Jennifer Ferguson 69 2019 CanLIIDocs 3798 Crown’s Newsletter Please direct all communications to the Editor-in-Chief at: Volume Ten December 2019 [email protected] © 2019 Ontario Crown The editorial board invites submissions for Attorneys’ Association publication on any topic of legal interest in Any reproduction, posting, repub- the next edition of the Crown’s Newsletter. lication, or communication of this newsletter or any of its contents, in Submissions have no length restrictions whole or in part, electronically or in 2019 CanLIIDocs 3798 print, is prohibited without express but must be sent in electronic form to the permission of the Editorial Board. Editor-in-Chief by March 31, 2020 to be considered for the next issue. For other submission requirements, contact the Editor- in-Chief. Cover Photo: © 2019 Crown Newsletter Editor-in-Chief James Palangio Editorial Board Ontario Crown Attorneys Association Jennifer Ferguson Suite 2100, Box #30 Lisa Joyal 180 Dundas Street West Rosemarie Juginovic Toronto, Ontario M5G 1Z8 Copy Editor Ph: (416) 977-4517 / Fax: (416) 977-1460 Matthew Shumka Editorial Support Allison Urbshas 1 FROM THE EDITORIAL BOARD James Palangio, editor-in-chief Jennifer Ferguson, Lisa Joyal & Rosemarie Juginovic The Crown Newsletter would like to acknowledge the contribution to this publication of David Boulet, Crown Attorney, Lindsay, for his years of support and contributions in providing a comprehensive review of secondary source materials. -

Paradigms of Restraint

02__MURPHY.DOC 5/27/2008 1:44:55 PM PARADIGMS OF RESTRAINT ERIN MURPHY† ABSTRACT Incapacitation of dangerous individuals has conventionally entailed the exercise of physical control over an actual body: the state confines the person in jail. But advances in technology have changed that convention. A variety of new technologies—such as GPS tracking bracelets, biometric scanners, online offender indexes, and DNA databases—give the government power to control dangerous persons without relying on any exertion of physical control. The government can track the location of a person in real time, receive remote notification that an individual has ingested alcohol, or electronically zone someone into a home or out of a public park. It can prove conclusively that a particular person wore a hat or took a sip from a discarded soda can, or identify a single face in a ten thousand–person crowd. In this day and age, restraint of the dangerous can be as much about keeping people out of a place as it used to be about locking them up in one. But whereas physical incapacitation of dangerous persons has always invoked some measure of constitutional scrutiny, virtually no legal constraints circumscribe the use of its technological counterpart. Across legal doctrines, courts erroneously treat physical deprivations Copyright © 2008 by Erin Murphy. † Assistant Professor, University of California, Berkeley (Boalt Hall). I owe a debt of gratitude to Carol Steiker, who invited me to participate in the Conference on Criminal Procedure Stories at Harvard Law School at which a preliminary version of this work was given, and to Dan Richman, whose superb piece on United States v.