An Evaluation of Existing Income Tax Regimes for Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific

Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific By Aim Sinpeng (University of Sydney), Fiona Martin (University of Sydney), Katharine Gelber (University of Queensland), and Kirril Shields (University of Queensland). July 5th 2021 Final Report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award Acknowledgements We would like to thank our Facebook research colleagues, as well as our researchers Fiona Suwana, Primitivo III Ragandang, Wathan Seezar Kyaw, Ayesha Jehangir and Venessa Paech, co-founder of Australian Community Managers. The research grant we received from Facebook was in the form of an “unrestricted research gift.” The terms of this gift specify that Facebook will not have any influence in the independent conduct of any studies or research, or in the dissemination of our findings. © Dept. Media and Communications, The University of Sydney, and The School of Political Science and International Studies, The University of Queensland Cover photo: Jon Tyson on Unsplash Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .......................... 1 2. Introduction ................................. 3 3. Literature review. 6 4. Methodology ................................ 8 5. Defining hate speech ........................ 11 6. Legal analysis and findings ................... 13 7. Facebook internal regulatory systems analysis ... 18 8. Country case studies ........................ 22 9. Conclusion ................................. 39 10. Challenges for future research ............... 40 11. Reference List ............................. 41 1. Executive summary This study examines the regulation of hate speech on countries where the issue of LGBTQ+ is politicised at Facebook in the Asia Pacific region, and was funded the national level. through the Facebook Content Policy Research on Social • LGBTQ+ page administrators interviewed for our Media awards. It found that: case studies had all encountered hate speech on their • The language and context dependent nature of hate group’s account. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

The Value of Public Service Media

The Value of Public Service Media T he worth of public service media is under increasing scrutiny in the 21st century as governments consider whether the institution is a good investment and a fair player in media markets. Mandated to provide universally accessible services and to cater for groups that are not commercially attractive, the institution often con- fronts conflicting demands. It must evidence its economic value, a concept defined by commercial logic, while delivering social value in fulfilling its largely not-for-profit public service mission and functions. Dual expectations create significant complex- The Value of ity for measuring PSM’s overall ‘public value’, a controversial policy concept that provided the theme for the RIPE@2012 conference, which took place in Sydney, Australia. This book, the sixth in the series of RIPE Readers on PSM published by NORDI- Public Service Media COM, is the culmination of robust discourse during that event and the distillation of its scholarly outcomes. Chapters are based on top tier contributions that have been revised, expanded and subject to peer review (double-blind). The collection investi- gates diverse conceptions of public service value in media, keyed to distinctions in Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Fiona Martin (eds.) the values and ideals that legitimate the public service enterprise in media in many countries. Fiona Martin (eds.) Gregory Ferrell Lowe & RIPE 2013 University of Gothenburg Box 713, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 31 786 00 00 (op.) Fax +46 31 786 46 55 E-mail: -

REPORT February 2021 This Report Has Been Prepared by Australian Aged Care Collaboration

Australian Aged Care Collaboration REPORT February 2021 This report has been prepared by Australian Aged Care Collaboration. REPORT VERSION: Final DATE: February 2021 CONTACT DETAILS: Kyle Cox National Campaign Director – Australian Aged Care Collaboration T: +61 481 903 156 | E: [email protected] W: careaboutagedcare.org.au Australian Aged Care Collaboration CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 KEY STATISTICS 14 SECTION 1 – CHALLENGES IN THE AUSTRALIAN AGED CARE SYSTEM 16 1.1 Funding and financing for aged care 1.2 More than 20 reviews in 20 years – why is the system still failing to meet community expectations? 1.3 Workforce challenges 1.4 COVID-19 SECTION 2 – TYPES OF AGED CARE IN AUSTRALIA 30 2.1 Who provides aged care services? 2.2 Home care and support - for people living in their own home. 2.3 Residential aged care services – for people living in communal homes. 2.3.1 The majority of residential aged care providers are small, not-for-profit organisations SECTION 3 – WHO CAN FIX AUSTRALIA’S AGED CARE SYSTEM? 43 3.1 Critical decision makers 3.2 Everyone can play a part 3.3 Australia’s 30 ‘oldest’ electorates 3.4 The 15 marginal seats from Australia’s 30 ‘oldest’ electorates APPENDIX 53 Full list of Australia’s 151 House of Representatives electorates It’s Time to Care About Aged Care Report - February 2021 3 Australian Aged Care Collaboration FOREWORD Over the past two years, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety has heard troubling accounts of under-resourcing, neglect, staff shortages and cases of abuse at residential aged care homes. -

Fiona Martin MP Consumer Sentiment at Its Highest in 11 Years

BUDGET 2021 NEWSLETTER FIONA PROTECTING THE GREEN SUPPORTING YOUR LOCAL MECHANIC MARTIN MP AND GOLD BELL FROG FEDERAL MEMBER FOR REID The Green and Gold Bell Frog is an endangered Everyone who drives a car needs a mechanic they can species found at Sydney Olympic Park in Homebush. trust. For many families the same mechanic is used Under the Community Environment Program, the for every household car. The Morrison Government SECURING AUSTRALIA’S RECOVERY Sydney Olympic Park Authority (SOPA) received a is committed to ensuring a competitive automotive $18,900 grant to expand the frog habitat to improve sector in Australia and supporting independent connectivity between ponds and hopefully boost mechanics. breeding. When I visited Mortlake Automotive with Minister A MESSAGE FROM Assistant Minister for the Environment, Trevor Evans Michael Sukkar, mechanics Frank and Greg told Fiona Dear resident, MP and I visited the park to check me about the troubles they faced getting data from out the project and hear about manufacturers. Mechanics like Frank and Greg Australia has come a long way since the first cases of the work SOPA do. only want to provide their loyal customers with the COVID early last year. All Australians should be proud highest quality service. That’s why the Government is of the role they have played in supressing the virus and Learn more about the project legislating to force manufacturers to provide fair access maintaining low rates of infection. by scanning the QR code. to car repair information for independent repairers. I would like to acknowledge all the frontline health workers throughout this pandemic. -

Morrison's Miracle the 2019 Australian Federal Election

MORRISON'S MIRACLE THE 2019 AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL ELECTION MORRISON'S MIRACLE THE 2019 AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL ELECTION EDITED BY ANIKA GAUJA, MARIAN SAWER AND MARIAN SIMMS In memory of Dr John Beaton FASSA, Executive Director of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia from 2001 to 2018 and an avid supporter of this series of election analyses Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463618 ISBN (online): 9781760463625 WorldCat (print): 1157333181 WorldCat (online): 1157332115 DOI: 10.22459/MM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Scott Morrison Campaign Day 11. Photo by Mick Tsikas, AAP. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Figures . ix Plates . xiii Tables . .. xv Abbreviations . xix Acknowledgements . xxiii Contributors . xxv Foreword . xxxiii 1 . Morrison’s miracle: Analysing the 2019 Australian federal election . 1 Anika Gauja, Marian Sawer and Marian Simms Part 1. Campaign and context 2 . Election campaign overview . 21 Marian Simms 3 . The rules of the game . 47 Marian Sawer and Michael Maley 4 . Candidates and pre‑selection . .. 71 Anika Gauja and Marija Taflaga 5 . Ideology and populism . 91 Carol Johnson 6 . The personalisation of the campaign . 107 Paul Strangio and James Walter 7 . National polling and other disasters . 125 Luke Mansillo and Simon Jackman 8 . -

Foundation Annual Report 2017–18

Foundation Annual Report 2017–18 Foundation Annual Report 2017 –18 4 CONTENTS Chair’s report 6 Foundation overview Foundation Board 13 About the Foundation 14 Support Ways of giving 16 Members 18 Donors 2017–18 37 Select gifts 45 Financial statements Independent auditor’s report 71 Directors’ report 74 Financial statements 84 Notes 88 Directors’ declaration 91 NGA Foundation Annual Report 2017–18 5 CHAIR’S REPORT I am delighted to present the National Gallery James O Fairfax Theatre to $1.6 million. of Australia Foundation Annual Report 2017–18. These necessary upgrades will enhance the Through this publication, we enthusiastically experience of all visitors through improved acknowledge and celebrate our generous access, usability and technology. The theatre community of supporters who have enabled will continue to be named for James for the Foundation to continue to support the another twenty years. National Gallery through our collective Several gifts of works of art were given fundraising efforts. in honour of Dr Gerard Vaughan AM who In 2017–18, the Foundation received donations retired as Director of the National Gallery of cash and works of art with a combined on 1 July 2017. Australian artist John Olsen value of $12.623 million. These generous generously gave his 2016 painting Dingo gifts underpinned our many successes which Country, Foundation Board director Philip include acquiring works of art for the national Bacon AM gifted a rare painting by Girolamo collection, developing and staging of important Nerli, Apia, Samoa 1892, and Don Holt gifted exhibitions and supporting the National a major painting by Indigenous artist Cowboy Gallery’s Learning and Access program and Louie Pwerle from the Northern Territory. -

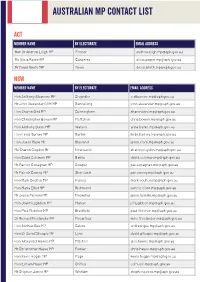

Australian Mp Contact List

AUSTRALIAN MP CONTACT LIST ACT MEMBER NAME BY ELECTORATE EMAIL ADDRESS Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP Fenner [email protected] Ms Alicia Payne MP Canberra [email protected] Mr David Smith MP Bean [email protected] NSW MEMBER NAME BY ELECTORATE EMAIL ADDRESS Hon Anthony Albanese MP Grayndler [email protected] Mr John Alexander OAM MP Bennelong [email protected] Hon Sharon Bird MP Cunningham [email protected] Hon Christopher Bowen MP McMahon [email protected] Hon Anthony Burke MP Watson [email protected] Hon Linda Burney MP Barton [email protected] Hon Jason Clare MP Blaxland [email protected] Ms Sharon Claydon MP Newcastle [email protected] Hon David Coleman MP Banks [email protected] Mr Patrick Conaghan MP Cowper [email protected] Mr Patrick Conroy MP Shortland [email protected] Hon Mark Coulton MP Parkes [email protected] Hon Maria Elliot MP Richmond [email protected] Mr Jason Falinski MP Mackellar [email protected] Hon Joel Fitzgibbon MP Hunter [email protected] Hon Paul Fletcher MP Bradfeld [email protected] Dr Michael Freelander MP Macarthur [email protected] Hon Andrew Gee MP Calare [email protected] Hon Dr David Gillespie MP Lyne [email protected] Hon Alexander Hawke MP Mitchell [email protected] Mr Christopher Hayes MP Fowler [email protected] Hon Kevin Hogan MP Page [email protected] Hon Edham Husic MP Chifey [email protected] -

Journal of the Australasian Tax Teachers Association

A U S T R A L A S I A N TAX TEACHERS ASSOCIAASSOCIATIONTION JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN TAX TEACHERS ASSOCIATION 2013 Vol.8 No.1 Edited by Postal Address: JATTA, c/o School of MARK R KEATING Taxation and Business Law University of New South Wales NSW 2052 Australia Kathrin Bain Ph: +61 2 9385 9541 E: [email protected] The Journal of the Australasian Tax Teachers Association (‘JATTA’) is a double blind, peer reviewed journal. The Journal is normally published annually, subsequent to the Association’s annual conference. The Australasian Tax Teachers Association (‘ATTA’) is a non-profit organisation established in 1987 with the goal of improving the standard of tax teaching in educational institutions across Australasia. Our members include tax academics, writers, and administrators from Australia and New Zealand. For more information about ATTA refer to our website (hosted by ATAX at the University of New South Wales) at http://www.asb.unsw.edu.au/schools/taxationandbusinesslaw/atta . Please direct your enquiries regarding the Journal to the Editor-in-Chief: Professor Dale Pinto Professor of Taxation Law School of Business Law and Taxation Curtin University GPO BOX U1987 Perth WA 6845 E: [email protected] Editorial Board of the Journal of Australasian Tax Teachers Association: Professor Dale Pinto , Curtin University, Perth, Australia (Editor-in-Chief) Professor Neil Brooks , Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, Toronto, Canada Associate Professor Paul Kenny , Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia Professor Margaret -

Ms Bridget Archer MP Ms Gladys Liu MP

Barton Deakin Brief: New Coalition MPs and Senators 31 May 2019 The 2019 election will see twenty-seven new Coalition Parliamentarians, sixteen of whom will sit in the House of Representatives and eleven will sit in the Senate. Of the new Parliamentarians in the Lower House, there are two new Nationals MPs, three new Liberal National Party MPs and eleven new Liberal Party MPs. Of the new Parliamentarians in the Upper House, there is one new Nationals Senator, one new Country Liberal Party Senator, three new Liberal National Party Senators and six new Liberal Party Senators. House of Representatives: Ms Bridget Archer MP Liberal Party Member for Bass, Tasmania Bridget Archer (43) won the seat of Bass over incumbent Labor MP, Ross Hart. Bridget holds the seat by 0.4 per cent and recorded a 5.9 per cent swing in her favour. Bridget is a local farmer and the Mayor of George Town on the North Coast of Tasmania. She is a graduate of the University of Tasmania and holds a Bachelor of Arts. Ms Gladys Liu MP Liberal Party Member for Chisholm, Victoria After her victory in the marginal seat of Chisholm, Gladys Liu (55) will be the first Chinese woman to sit in the Federal House of Representatives. Not expected to win after the departure of former Liberal MP Julia Banks, Gladys held the seat notwithstanding a 2.2 per cent swing against her. Born in Hong Kong, Gladys moved to Melbourne on a scholarship to study speech pathology at La Trobe University and begun her career as speech pathologist and small business owner. -

2019 Federal Election Seats to Watch Overview Current Polling

Barton Deakin Brief: 2019 Federal Election Seats to Watch 15 May 2019 Overview The 2019 Federal Election will take place this Saturday, 18 May 2019. As per our Barton Deakin Election Snapshot brief, the election will see the incumbent Liberal-National Government seek a third term in office against Opposition, the Australian Labor Party. The following brief outlines the current state of play in key marginal seats leading up to the election according to recent polls and betting market odds. This brief also provides an analysis of prominent ‘seats to watch’, a quick view of the electorates in which the election will be won or lost across Australia and the on the ground issues that could swing voters in these seats. Current Polling: Poll Result Date Newspoll 51 (ALP) – 49 (Coalition) 13 May 2019 Fairfax Ipsos 52 (ALP) – 48 (Coalition) 5 May 2019 Galaxy 52 (ALP) – 48 (Coalition) 27 April 2019 Roy Morgan 52 (ALP) – 48 (Coalition) 14 May 2019 Essential 52 (ALP) – 48 (Coalition) 6 May 2019 Ladbrokes Politics $1.12 (ALP) - $6.00 (Coalition) 14 May 2019 Sportsbet $1.14 (ALP) - $5.50 (Coalition) 14 May 2019 Marginal Seats: According to the Australian Electoral Commission, a seat is marginal if it falls within a 6 per cent margin at the last election. Betting Markets Electorate State Margin** Sitting Member Candidate Recent Poll 14/05/2019 Chris Crewther ALP $1.14, Dunkley (*) VIC -1 Peta Murphy (ALP) (LIB) Coalition $4.50 Corangamite Sarah Henderson ALP $1.33, 52-48 (Coalition- VIC -0.03 Libby Coker (ALP) (*) (LIB) Coalition $3 ALP) Michelle Landry -

It's Time to Care About Aged Care Report

Australian Aged Care Collaboration REPORT February 2021 This report has been prepared by Australian Aged Care Collaboration. REPORT VERSION: Final DATE: February 2021 CONTACT DETAILS: Kyle Cox National Campaign Director – Australian Aged Care Collaboration T: +61 481 903 156 | E: [email protected] W: careaboutagedcare.org.au Australian Aged Care Collaboration CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 KEY STATISTICS 14 SECTION 1 – CHALLENGES IN THE AUSTRALIAN AGED CARE SYSTEM 16 1.1 Funding and financing for aged care 1.2 More than 20 reviews in 20 years – why is the system still failing to meet community expectations? 1.3 Workforce challenges 1.4 COVID-19 SECTION 2 – TYPES OF AGED CARE IN AUSTRALIA 30 2.1 Who provides aged care services? 2.2 Home care and support - for people living in their own home. 2.3 Residential aged care services – for people living in communal homes. 2.3.1 The majority of residential aged care providers are small, not-for-profit organisations SECTION 3 – WHO CAN FIX AUSTRALIA’S AGED CARE SYSTEM? 43 3.1 Critical decision makers 3.2 Everyone can play a part 3.3 Australia’s 30 ‘oldest’ electorates 3.4 The 15 marginal seats from Australia’s 30 ‘oldest’ electorates APPENDIX 53 Full list of Australia’s 151 House of Representatives electorates It’s Time to Care About Aged Care Report - February 2021 3 Australian Aged Care Collaboration FOREWORD Over the past two years, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety has heard troubling accounts of under-resourcing, neglect, staff shortages and cases of abuse at residential aged care homes.