Understanding the Cultural Historical Value of the Wadden Sea Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Viewing Archiving 300

VU Research Portal Network infrastructure and regional development Vleugel, J.; Nijkamp, P.; Rietveld, P. 1990 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Vleugel, J., Nijkamp, P., & Rietveld, P. (1990). Network infrastructure and regional development. (Serie Research Memoranda; No. 1990-67). Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 M(jo- 6j Faculteit der Economische Wetenschappen en Econometrie ET 05348 Serie Research Memoranda Network Infrastructure and Regional Development; A Case Study for North-Holland J.M. Vleugel P. N ij kamp P. Rietveld Research Memorandum 1990-67 December 1990 vrije Universiteit amsterdam CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. INFRASTRUCTURE AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 3. BACKGROUND 5 4. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone -

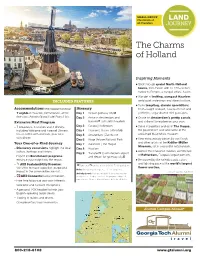

The Charms of Holland

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 24 Travele rs JO URNEY The Charms of Holland Inspiring Moments > Stroll through quaint North-Holland towns, from Hoorn with its 17th-century harbor to Bergen, a tranquil artists’ haven. > Wander in inviting, compact Haarlem amid quiet waterways and vibrant culture. INCLUDED FEATURES > Taste tempting, classic specialties: Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary fresh-caught seafood, Gouda cheese and – 7 nights in Haarlem, Netherlands, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city poffertjes , sugar-dusted mini-pancakes. first-class Amrath Grand Hotel Frans Hals. Day 2 Arrive in Amsterdam and > Cruise on Amsterdam’s pretty canals transfer to hotel in Haarlem and strike off to explore on your own. Extensive Meal Program – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Gouda | Rotterdam > Delve into politics and art in The Hague, including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Haarlem | Hoorn | Afsluitdijk the government seat and home of the tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Day 5 Amsterdam | Zandvoort acclaimed Mauritshuis museum. with dinner. Day 6 Hoge Veluwe National Park > View extraordinary pieces by van Gogh and other artists at the Kröller-Müller Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Day 7 Aalsmeer | The Hague Museum, set in a beautiful national park. – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 8 Haarlem culture, heritage and history. > Admire the innovative modern architecture Day 9 Transfer to Amsterdam airport of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port city. – Expert-led Enrichment programs and depart for gateway city enhance your insight into the region. > Be wowed by the kaleidoscopic colors and lightning pace of the world’s largest – AHI Sustainability Promise: Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. -

Tourismus in Niedersachsen Und Speziell Im Reisegebiet Harz - Entwicklung Von 2000 Bis 2011

Dr. Wolfgang Vorwig (Tel. 0511 9898-2347) Tourismus in Niedersachsen und speziell im Reisegebiet Harz - Entwicklung von 2000 bis 2011 Niedersachsen bietet auf Grund seiner vielfältigen land- nach Deutschland, gegenüber dem Jahr 1999 entsprach dies schaftlichen Strukturen interessante Reise- und Urlaubszie- einem Zuwachs von 6,1 %. Mit 347,4 Mio. Übernachtungen le für seine Besucher. Diese reichen von Küsten- über wurden im Expojahr 5,5 % mehr gebucht als im Vorjahr. Die Heide- bis zu Mittelgebirgslandschaften. Weitreichende Ankünfte gingen bis zum Jahr 2003 wieder leicht bis auf knapp Angebote ermöglichen die unterschiedlichsten Urlaubsfor- 112,6 Mio. zurück um dann ab 2004 wieder über das Niveau men von z.B. Badeurlaub oder Rad-, Wander-, Wellness- des Jahres 2000 anzusteigen. Bei den Übernachtungen verlief und Reiturlaub. Auf Grund dieser breit gefächerten Mög- die Entwicklung ähnlich. Konnte dieses Niveau im Nachexpo- lichkeiten ist der Tourismus ein wichtiger Faktor für die jahr noch gehalten werden, wurde es in den Folgejahren wie- niedersächsische Wirtschaft. Im nachfolgenden Aufsatz der unterschritten. Seit 2006 hat die Zahl der Übernachtun- soll die Entwicklung des Tourismus in Niedersachsen sowie gen in Deutschland von einer Unterbrechung im Jahr 2009 im Reisegebiet Harz in den Jahren 2000 bis 2011 darge- (-0,2 % gg. dem Vorjahr) einmal abgesehen aber kontinuier- stellt werden. Der Harz soll hier näher betrachtet werden, lich zugenommen. So wurde 2011 mit 394 Mio. Übernach- da dieses Reisegebiet in der Vergangenheit wiederholt Ge- tungen ein neuer Höchstwert erreicht. genstand der Presseberichterstattung war. In den Grafi ken 1 und 2 sind die Entwicklungen der An- künfte und Übernachtungen in Deutschland im Vergleich Niedersachsen im Vergleich zur Bundesrepublik zu Niedersachsen als Messzahlen dargestellt. -

Gemeinde Wöhrden

Gemeinde Im Herzen der Marsch Wöhrden Im Herzen der Marsch 1 ... da ist Musik drin Wo der Plattenteller sich noch dreht, aus der Jukebox Bei uns trifft man übrigens noch die alteingesessenen „ltsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie" ertönt, der Kaffee liebevoll Wöhrdener, denn die sind geblieben und sorgen beim von Hand aufgebrüht wird und das Küchenteam regio Kartenspiel ohne viel zu „schnacken" für nostalgisch nale Köstlichkeiten auf einem historischen Kohleherd romantische Stimmung. zubereitet, ist der Gasthof Oldenwöhrden. Wenn Sie durch unser Sandsteinportal von 1634 gehen, Seit 1914 in Familienbesitz, sorgen wir bereits in vierter treten Sie in eine Welt, in der Tradition dem Heute eine Generation für das Wohl unserer Gäste. Die im modernen charmante Zuflucht bietet. Landhausstil eingerichteten Zimmer versprühen nordischen Charme und setzen individuelle Akzente. Ihre Elsbe Paulsen Auch bei Ihrem leiblichen Wohl legen wir Wert auf ursprüngliche Qualität: Unsere frische, vielfältige und • 13 Hotelzimmer und 4 Suiten regionale Küche vom Küchenchef und seinem Team • Naturbadeteich und Sauna genießen Sie in unserer mit historischen Fotografien • Restaurant, Wintergarten und Terrasse dekorierten und mit samtbezogenen Stühlen und Sofas möblierten Gaststube - gerne musikalisch untermalt von • Saal für bis zu 250 Personen Ihren Lieblingsoldies aus unserer Jukebox. Landhotel Gasthof Oldenwöhrden Auch in unserem Wintergarten oder auch auf unserer Große Straße 17 in D-25797 Wöhrden großzügigen Terrasse lässt es sich vorzüglich speisen. Telefon: 04839-95310 [email protected] 02 Gemeinde Wöhrden Inhalt 05 l Grußwort 17 l Lütt un Groot 06 l Impressionen 18 l Gemeindekarte 10 l Geschichtliches 21 l Die St. Nicolai-Kirche 11 l Gemeinschaftspraxis Wöhrden 24 l Patenschaft & Partnerschaften 12 l Wöhrden Heute 27 l Sportverein Wöhrden 13 l Wohngebiet Op´n Pasterkroog 28 l Kulturpfad Wöhrden 15 l Freie Waldorfschule Wöhrden 34 l Impressum 16 l Wöhrden und die Windenergie 8x im Norden GmbH & Co. -

Findbuch Abteilung III 1945

Findbuch Abteilung III 1945 - 1969 Lfd. -Nr. Inhalt Zeitraum Allgemeine Verwaltung 1. Bürgermeister 0290 Bewerber für die Bürgermeisterwahl 1946 - 1962 0417 Bürgermeister Dr. Wilkens: 12 Jahre gemeinsame Arbeit für 1962 - 1986 die Stadt Heide (1962-74); Weitere 12 Jahre gemeinsame Arbeit. Tätigkeit Bürgermeister Dr. Wilkens (1974-86) 0925 Bürgermeister Dr. Harald Boysen: Bewerbung, Pers.- 1950 - 1962 Vorgänge. Bürgermeister-Wahl, Verwaltungsstreitsache (1950-56); Glückwunschschreiben an Bürgermeister Dr. 00Boysen (1959-61); Verabschiedung Dr. Boysen (1962) 0950 Bürgermeister Dr. Hermann Hadenfeldt (1903-09, 1928-37, 1903 - 1949 1946-49); Ehrenbürger s.u. III 0105 0951 Bürgermeister Karl Herwig (Kopien persönlicher Unterlagen, 1937 - 1987 zugleich Tätigkeit in Heide und Wesselburen - s.u. III 1281) 0951a Vorgänge zur Bürgermeisterwahl 1956 - 1962 1096 Bürgermeister Heinrich Pleus (siehe auch II 228) 1932 - 1959 1203 Widersprüche des Bürgermeisters 1953 - 1962 1229 Bürgermeister der Stadt Heide: Hinweise und Zusammen- stellungen 2. Magistrat 0139 Geschäftsordnung des Magistrats (1957, 1967, 1978) 1957 - 1978 0140 Sachgebietszuteilung des Magistrats: Verzeichnisse 1970, 1970 - 1977 1973, 1974,1977 Sachgebietsverteilung des Magistrates 1950 - 1993 0657 Einladungen zu den Sitzungen des Magistrats (1962-71, 1962 - 1980 1976-80) 0800 Magistrat: Allgemeiner Teil 1945 - 1982 1558 Magistratsbeschlüsse 1961 1753 Sachgebietsverteilung des Magistrats 1950 - 1993 3. Magistratsprotokolle 0115 20.02.1946 - 03.04.1947 1946 - 1947 0116 10.04.1947 - 09.09.1948 -

Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag Umdruck 19/660

Elterninitiative Gesche Holst – Dirk Richter: Anhörung zur Drucksache 19/372 Nach dem Zusammenschluss der Schulstandorte Hennstedt, Lunden und Lehe, mit Hauptstandort Hennstedt und den beiden Außenstellen Lunden und Lehe, ist es nicht zur erhofften Verbesserung der Schulsituation vor Ort gekommen, sondern hat sich durch die Jahre eher entgegengesetzt entwickelt. Aus diesem Grund kam es bereits vor Schließung der Grundschule in Lehe und der Gemeinschaftsschule in Lunden zu sinkenden Schülerzahlen, durch Ummeldung von aktuellen Schülern bzw. fehlenden Anmeldungen von potentiellen Schülern. Immer mehr Schüler haben sich für den Schulbesuch an der Eider-Treene-Schule (ETS) mit Oberstufe in Tönning und der Außenstelle in Friedrichstadt entschieden. Leider wurde nicht zeitnah und konsequent von dem zuständigen Schulträger und der Schulleitung auf die Entwicklung reagiert und im Mai 2015 wurde zum Schuljahr 2015/2016 die Grundschule in Lehe und die Gemeinschaftsschule in Lunden geschlossen und die betroffenen Schüler waren gezwungen sich innerhalb einer kurzen Zeit eine neue Schule zu suchen. Wie bereits erwähnt haben sich vor Schließung der weiterführenden Schule in Lunden Schüler aus dem Raum Lunden die ETS in Tönning und in Friedrichstadt entschieden, jedoch keinen Anspruch auf Übernahme der Schülerbeförderungskosten gestellt, da die nächstgelegene weiterführende Schule in Lunden lag. Diese Situation hat sich nach der o. a. Schließung jedoch wesentlich geändert. Aktuell erfolgt eine gesamte bzw. anteilige Zahlung der Schülerbeförderungskosten an die Gymnasien in Heide und Husum, zur Gemeinschaftsschule Hennstedt, Wesselburen und Heide sowie zur ETS Friedrichtstadt, Außenstelle der ETS Tönning aufgrund der bestehenden ÖPNV-Verbindung zu schulgünstigen Zeiten. Seite 1 von 6 Elterninitiative Gesche Holst – Dirk Richter: Anhörung zur Drucksache 19/372 Des Weiteren werden die dementsprechenden Schülerbeförderungskosten für Schüler aus dem Raum Lunden zum Gymnasium nach St. -

Archaeological Surveys on the German North Sea Coast Using High-Resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar Data

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-3/W2, 2017 37th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, 8–12 May 2017, Tshwane, South Africa Archaeological Surveys on the German North Sea Coast Using High-Resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar Data Martin Gade 1*, Jörn Kohlus 2, and Cornelia Kost 3 1 Institut für Meereskunde, Universität Hamburg, 20146 Hamburg, Germany – [email protected] 2 LKN Schleswig Holstein, Nationalparkamt, 25832 Tönning, Germany 3 Wördemanns Weg 23a, 22527 Hamburg, Germany KEYWORDS: Wadden Sea, storm surge, SAR archaeology, TerraSAR-X, cultural traces, settlements ABSTRACT: We show that high-resolution space-borne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery with pixel sizes well below 1 m² can be used to complement archaeological surveys in areas that are difficult to access. After major storm surges in the 14th and 17th centuries, vast areas on the German North Sea coast were lost to the sea. Areas of former settlements and historical land use were buried under sediments for centuries, but when the surface layer is driven away under the permanent action of wind, currents, and waves, they appear again on the Wadden Sea surface. However, the frequent flooding and erosion of the intertidal flats make any archaeological monitoring a difficult task, so that remote sensing techniques appear to be an efficient and cost-effective instrument for any archaeological surveillance of that area. Space-borne SAR images clearly show remnants of farmhouse foundations and of former systems of ditches, dating back to the 14th and to the 16th/17th centuries. In particular, the very high-resolution acquisition (‘staring spotlight’) mode of the German TerraSAR/ TanDEM-X satellites allows for the detection of various kinds of residuals of historical land use with high precision. -

Fishing Shrimp in the Wadden Sea: the Extinction of a Traditional Practice in the Frisian Area of Bremerhaven (Weser Mouth) Anatole Danto, Henning Siats

Fishing shrimp in the Wadden Sea: the extinction of a traditional practice in the Frisian area of Bremerhaven (Weser mouth) Anatole Danto, Henning Siats To cite this version: Anatole Danto, Henning Siats. Fishing shrimp in the Wadden Sea: the extinction of a traditional practice in the Frisian area of Bremerhaven (Weser mouth). Oceans Past VII Conference - Tracing hu- man interactions with marine ecosystems through deep time: implications for policy and management, Oct 2018, Bremerhaven, Germany. 2018. hal-01907250 HAL Id: hal-01907250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01907250 Submitted on 28 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Fishing shrimp in the Wadden Sea: the extinction of a Eco-anthropology traditional practice in the Frisian area of Bremerhaven (Weser mouth) Wremen village 1 2 Environmental history Anatole DANTO , Henning SIATS Land Wursten 1 : CNRS PhD candidate / International research network ApoliMer : political anthropology of the Sea / Corresponding author : [email protected] UMR 6051 ARENES : Research center on policy action in Europe, Institute of political studies of Rennes / UMR 7372 CEBC : Chizé Centre for Biological Studies Interdisciplinarity 2 : Director of the Museum für Wattenfischerei of Nordseebad Wremen Lower Saxony state Abstract Shrimp sled and trap fishing For millennia, coastal societies in the Wadden Sea have Traps as fundamental technology practiced environmental food uses along the coasts of this ▪ Traps are among the oldest known fishing gears. -

Beschluss Des Präsidiums Des Amtsgerichts Meldorf Betreffend Die Richterliche Geschäftsverteilung Ab Dem 01.09.2021

L 320 E Beschluss des Präsidiums des Amtsgerichts Meldorf betreffend die richterliche Geschäftsverteilung ab dem 01.09.2021 Der Richter Waege verlässt aufgrund einer temporären Abordnung das Gericht, ohne dass zunächst eine Ersatzkraft zur Verfügung steht. Deshalb sind die Vertretungsregelungen zum 01.09.2021 anzupassen. Dezernat I Direktor des Amtsoeric hts Prof. Dr. Schulz 1. Entschuldungssachen 2. Der Bestand des Dezernats I an Zivilsachen einschließlich der als Zivilsachen zu behandelnden AR- und H-Sachen zum 31 .12.2O2O sowie Zivilsachen nach dem jeweils geltenden Turnusplan - mit Ausnahme der WEG-Sachen - sowie von den als Zivilsachen zu behandelnden AR- und H-Sachen die Endziffern 6 u. 7 3. Güterichter nach §§ 278 Abs. 5 ZPO, 36 Abs. 5 FamFG 4. Richterablehnungen gemäß § 24 StPO. 5. Ablehnungen von Rechtspflegerinnen und Rechtspflegern Vertreterin zu Ziff. 2, 3: Richter am Amtsgericht Meppen Vertreter zu Ziff. 4 und 5: Richter am Amtsgericht - als stellvertretender Direktor - Dr. Hansen-Nootbaar Ersatzv erlreler zu Ziff .2 3 und 4 Richter am Amtsgericht Zacharias Dezernat ll Richter am Amtsoericht - als stell nder Direktor - Dr. Hansen-Nootbaar '1. Güterichter nach §§ 278 Abs. 5 ZPO, 36 Abs. 5 FamFG 2. Bereitschaftsrichter 2 3. Vorsitzender des Jugendschöffengerichts einschließlich der VRJs-Sachen, die sich aus diesen ergeben und von auswärtigen Gerichten und die sich aus den Jugendschöffensachen ergebenden Bewährungsaufsichten 4. Vorsitzender des Ausschusses zur Wahl der Jugendschöffen gemäß §§ 40 GVG, 35 JGG 5. Gs - Sachen gegen Eruvachsene Vertreter zu Ziffer 1 : Direktor des Amtsgerichts Prof. Dr. Schulz Vertreterin zu Ziffer 3 bis 5 Richterin am Amtsgericht Petersen Die Vertretung hinsichtlach Zifi. 2. wtd durch den gemeinsamen Beschluss der Präsidien des Landgerichts ltzehoe und der Amtsgerichte ltzehoe und Meldorf zum gemeinsamen Bereitschaft sdienst besonders geregelt. -

KV Süddänemark-Dänisch Ohne Bild

Ministerium für Justiz, Arbeit und Europa des Landes Schleswig-Holstein Grænseoverskridende samarbejde med Region Syddanmark Rapport fra delstatsregeringen i Schleswig-Holstein om det grænseoverskridende samarbejde med Region Syddanmark ”At vokse sammen“ er det fælles anliggende for den slesvig-holstenske delstatsregering og Region Syddanmark. Begge sider er overbeviste om, at det grænseoverskridende samarbejde leverer betydelige impulser til den økonomiske, sociale og kulturelle udvikling i hele grænseregionen. Rapporten om det grænseoverskridende samarbejde med Region Syddanmark, som den slesvig-holstenske delstatsre-gering forelægger, viser tydeligt, med hvilke store skridt samarbejdet på tværs af landegrænser i de seneste år er gået fremad. De i rapporten beskrevne aktiviteter viser, at det stærke netværk i det dansk-tyske samarbejde, som dækker over mange emner, herved har en central rolle. Endvidere kan der også ses tydeligt, at dette partnerskab i høj grad fyldes med liv gennem et stort antal af lokale grænseoverskridende projekter. Det tysk-danske partnerskab er således et af de bedste eksempler på, hvordan samarbejdet på tværs af landegrænser får Europas medlemsstater til at vokse tættere sammen. Lad os i fællesskab fortsat arbejdere videre på dette. 2 Indholdsfortegnelse Forord............................................................................................................................ .....5 1. Indledning................................................................................................................. -

Dutch Waterways

distinguished travel for more than 35 years ALONG THE Dutch Waterways THE NETHERLANDS Hoorn Kampen Amsterdam Kröller-Müller Museum The North Hague Keukenhof Gardens Sea Delft Nijmegen Bruges Antwerp Ghent Maastricht GERMANY FLANDERS UNESCO World Heritage Site Brussels Cruise Itinerary Air Routing BELGIUM Land Routing May 1 to 9, 2021 elebrate the beauty of Holland and old-world Flanders Antwerp u Maastricht u Kröller-Müller Museum C Kampen u Hoorn u Keukenhof Gardens u Amsterdam in springtime. Cruise for seven nights aboard the exclusively 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada chartered, deluxe small river ship Amadeus Star when the 2 Brussels, Belgium/Ghent/ vibrant Dutch tulip fields are in bloom. Meet local residents Embark Amadeus Star during the exclusive River Life® Forum and discover the 3 Ghent/Bruges true essence of river life in the Low Countries. Expert-led 4 Antwerp excursions include the historic canals of Amsterdam, 5 Maastricht, the Netherlands, for the Netherlands storybook Bruges, the world-class Kröller-Müller American Military Cemetery Museum, the famous Keukenhof Gardens, Hoorn, 6 Nijmegen for the Kröller-Müller Museum Maastricht, the American Military Cemetery, Antwerp and 7 Kampen medieval Ghent. This comprehensive itinerary is an 8 Hoorn/Amsterdam for Keukenhof Gardens exceptional value, continually praised as the ideal 9 Amsterdam/Disembark ship/ Return to the U.S. or Canada Dutch and Flemish experience. The Hague Pre-Program and Amsterdam Post-Program Options are offered. Itinerary is subject to change. Exclusively Chartered New Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Star along the Dutch Waterways Included Features* On Board the Exclusively Chartered, New, Deluxe reserve early! Amadeus Star From $2595 per person, double occupancy (approximate land/cruise only)* u Seven-night cruise from Ghent, Belgium, to Amsterdam, the Netherlands.