“Jumping Through Hoops”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 AUGUST/SEPT 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 AUGUST/SEPT 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping you are all well and enjoying a Lyons Maid or two on the hotter days while watching Talking Pictures TV – your own personal trip to the flicks every day and no fleas! This month we bring you a wonderful new DVD Box set from Renown Pictures – The Comedy Collection Volume 3! We thought it was time we all had a jolly good laugh and with 11 films over 3 discs, starring some of the greatest British character actors you will see, it’s an absolute bargain at £20 for all 3 discs with free UK postage. Titles include: A Hole Lot of Trouble with Arthur Lowe, Victor Maddern and Bill Maynard; A Touch of The Sun with Frankie Howerd, Ruby Murray and Alfie Bass, once lost British comedy Just William’s Luck, fully restored to its former glory, Come Back Peter, with Patrick Holt and Charles Lamb, also once lost and never before released on DVD, as well as Where There’s A Will with George Cole and Kathleen Harrison, plus many more! More details overleaf. There’s an extra special deal on our Comedy Collection Volumes 1 and 2 as well. Regarding our events this year and next year, there is good news and bad news. Finally, the manager at the St Albans Arena has come back to the office and has secured 28th March 2021 for us. Sad news as it doesn’t look like we will be able to go ahead with any other event this year, including Stockport on Sunday 4th October. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

South African Women Poets, 2000-2015

ATLANTA REVIEW V o l u m e XXIV, I s s u e N u m bATLANTA e r 2 REVIEW i ATLANTA REVIEW at the Georgia Institute of Technology Editor Karen Head Managing Editor JC Reilly Design Editor Duo-Wei Yang Guest Editor Phillippa Yaa de Villiers Editor Emeritus Dan Veach ***** Editorial Staff Senior Reader Robert Wood Reader Andrea Rogers Reader Julie Weng Layout Assistant Jordan Davis ***** Atlanta Review logo designed by Malone Tumlin Davidson ii ATLANTA REVIEW Visit our website: www.atlantareview.com Atlanta Review appears in May and November. Subscriptions are $15 a year. Available in full text in Ebsco, ProQuest, and Cengage databases. Atlanta Review subscriptions are available through Ebsco, Blackwell, and Swets. Submission guidelines: Up to five poems, without identifying information on any poem. For more information, visit our website. Submission deadlines are as follows: June 1st (Fall issue) December 1st (Spring issue) Online submissions preferred: https://atlantareview.submittable.com/submit Postal mail submissions must include a stamped, self-addressed return envelope, and a cover letter listing poet’s contact informa- tion and a list of poem titles submitted. Please send postal mail submissions and subscriptions requests to: ATLANTA REVIEW 686 Cherry St. NW, Suite 333 Atlanta GA 30332-0161 © Copyright 2018 by Atlanta Review. ISSN 1073-9696 Atlanta Review is a nonprofit literary journal. Contributions are tax-deductible. ATLANTA REVIEW iii Welcome Winter has been tempestuous for many of our writers and subscribers this year. Even in Atlanta, we had a January snowstorm that shut down the city for a couple of days. -

Robert Hartford-Davis and British Exploitation Cinema of the 1960S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Corrupted, Tormented and Damned: Reframing British Exploitation Cinema and The films of Robert Hartford-Davis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Michael Ahmed, M.A., B.A. PhD University of East Anglia Faculty of Film and Television Studies January 2013 Abstract The American exploitation film functioned as an alternative to mainstream Hollywood cinema, and served as a way of introducing to audiences shocking, controversial themes, as well as narratives that major American studios were reluctant to explore. Whereas American exploitation cinema developed in parallel to mainstream Hollywood, exploitation cinema in Britain has no such historical equivalent. Furthermore, the definition of exploitation, in terms of the British industry, is currently used to describe (according to the Encyclopedia of British Film) either poor quality sex comedies from the 1970s, a handful of horror films, or as a loosely fixed generic description dependent upon prevailing critical or academic orthodoxies. However, exploitation was a term used by the British industry in the 1960s to describe a wide-ranging and eclectic variety of films – these films included, ―kitchen-sink dramas‖, comedies, musicals, westerns, as well as many films from Continental Europe and Scandinavia. Therefore, the current description of an exploitation film in Britain has changed a great deal from its original meaning. -

Teenagers, Everyday Life and Popular Culture in 1950S Ireland

Teenagers, Everyday Life and Popular Culture in 1950s Ireland Eleanor O’Leary, BA., MA. Submitted for qualification of PhD Supervised by Dr Stephanie Rains, Centre for Media Studies, National University of Ireland, Maynooth Head of Department: Dr Stephanie Rains Submitted October 2013 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ____________________________________ ID No. ____________________________________ Date: ____________________________________ Table of Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1 – Education and Opportunities........................................................................................... -

Ticket to Paradise

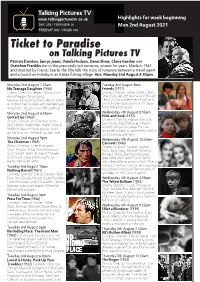

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 2nd August 2021 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Ticket to Paradise on Talking Pictures TV Patricia Dainton, Emrys Jones, Vanda Hudson, Denis Shaw, Claire Gordon and Gretchen Franklin star in this previously lost romance, unseen for years. Made in 1961 and directed by Francis Searle, the film tells the story of romance between a travel agent and a tourist on holiday in an Italian fishing village.Airs: Monday 2nd August 4:55pm. Monday 2nd August 7:25am Tuesday 3rd August 9pm My Teenage Daughter (1956) Friends (1971) Drama. Director: Herbert Wilcox. Stars: Drama. Director: Lewis Gilbert. Stars: Anna Neagle, Sylvia Syms, Sean Bury, Anicee Alvina and Ronald Norman Wooland & Wilfrid Hyde-White. Lewis. An orphaned French girl and A mother tries to deal with her teenage a rich English boy create a life apart daughter’s descent into delinquency. from the adult world. Monday 2nd August 6:35pm Wednesday 4th August 8:15am Go Kart Go (1963) Hide and Seek (1972) Action. Director: Jan Darnley-Smith. Children’s Film Foundation film with Star: Dennis Waterman, Frazer Hines & Gary Kemp, Roy Dotrice and Robin Askwith. A boy runs away from an Melanie Garland. Rival groups build approved school to convince his dad to go-karts to win the local go-kart race. go to Canada with him. Monday 2nd August 9pm Wednesday 4th August 10:30am The Chairman (1969) Carnival (1946) Action. Director: J Lee Thompson. Drama. Director: Stanley Haynes. Stars: Gregory Peck, Anne Heywood Stars: Sally Gray, Michael Wilding, and Conrad Yama. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 APRIL/MAY 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 APRIL/MAY 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping you are all well and safe, can you believe it, Talking Pictures TV is six in just a few weeks time! It doesn’t quite seem possible and with 6 million of you watching every week it does seem like Noel was right! The Saturday Morning Pictures ‘revival’ has been a real hit with you all and there’s lots more planned for our regular Saturday slot 9-12. Radar Men from the Moon and The Cisco Kid start on Saturday 1st May. GOOD NEWS! We have created a beautiful limited edition enamel badge for all you Saturday Morning Pictures TPTV is 6! club members, see page 7 for details. This month sees the release of two new box sets from Renown Pictures. Our very popular Glimpses collections continue with GLIMPSES VOLUME 5. Some real treats on the three discs, including fascinating footage of Manchester in the 60s, London in the 70s, a short film on greyhound racing in the 70s, The Hillman Minx and Sheffield in the 50s. Still just £20 with free UK postage! Also this month on DVD, fully restored with optional subtitles, you can all recreate Saturday Morning Pictures anytime you like with your own DVD set of FLASH GORDON CONQUERS THE UNIVERSE – just £15 with free UK postage. We’re delighted to announce that LOOK AT LIFE is finally in its rightful home on TPTV, starting in May. -

Glennon Doyle All Rights Reserved

This is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some names, identifying details and personal characteristics of the individuals involved have been changed. In addition certain people who appear in these pages are composites of a number of individuals and their experiences. Copyright © 2020 by Glennon Doyle All rights reserved. Published in the United States by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. THE DIAL PRESS is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Acknowledgment is made to M. Peck Scott (The Road Less Traveled) and William James (The Varieties of Religious Experience) for their presentation of the “the unseen order of things.” In addition, acknowledgment and appreciation is expressed to Professor Randall Balmer, whose 2014 Politico article “The Real Origins of the Religious Right” informed and impacted the “Decals” chapter of this book. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Daniel Ladinsky: “Dropping Keys” adapted from the Hafiz poem by Daniel Ladinsky from The Gift: Poems by Hafiz by Daniel Ladinsky, copyright © 1999 by Daniel Ladinsky. Used with permission. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: Five lines from “A Secret Life” from Landscape at the End of the Century by Stephen Dunn, copyright © 1991 by Stephen Dunn. Used with permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Writers House LLC: Excerpt from “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., published in TheAtlantic.com. This article appears in the special MLK issue print edition with the headline “Letter From Birmingham Jail” and was published in the August 1963 edition of The Atlantic as “The Negro Is Your Brother,” copyright © 1963 by Dr. -

Lindsay Anderson: Sequence and the Rise of Auteurism in 1950S Britain

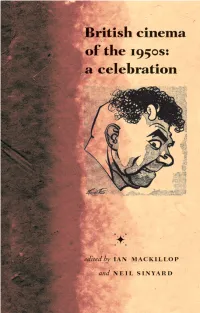

British cinema of the 1950s: a celebration MacKillop_00_Prelims 1 9/1/03, 9:23 am MacKillop_00_Prelims 2 9/1/03, 9:23 am British cinema of the 1950s: a celebration edited by ian mackillop and neil sinyard Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave MacKillop_00_Prelims 3 9/1/03, 9:23 am Copyright © Manchester University Press 2003 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, 10010, USA http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for 0 7190 6488 0 hardback 0 7190 6489 9 paperback First published 2003 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Fournier and Fairfield Display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow MacKillop_00_Prelims 4 9/1/03, -

British National Cinema

British national cinema With films as diverse as Bhaji on the Beach, The Dam Busters, Mrs Miniver, Trainspotting, The Draughtsman's Contract, and Prick Up Your Ears, twentieth- century British cinema has produced wide-ranging notions of British culture, identity and nationhood. British National Cinema is a comprehensive introduction to the British film industry within an economic, political and social context. Describing the development of the British film industry, from the Lumière brothers’ first screening in London in 1896 through to the dominance of Hollywood and the severe financial crises which affected Goldcrest, Handmade Films and Palace Pictures in the late 1980s and 1990s, Sarah Street explores the relationship between British cinema and British society. Using the notions of ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ cinema, the author demonstrates how British cinema has been both ‘respectable’ and ‘disreputable’ according to the prevailing notions of what constitutes good cinema. British National Cinema analyses the politics of film and establishes the difficult context within which British producers and directors have worked. Sarah Street questions why British film-making, production and distribution have always been subject to government apathy and financial stringency. In a comparison of Britain and Hollywood, the author asks to what extent was there a 'star system' in Britain and what was its real historical and social function. An examination of genres associated with British film, such as Ealing comedies, Hammer horror and 'heritage' films, confirms the eclectic nature of British cinema. In a final evaluation of British film, she examines the existence of 'other cinemas': film-making which challenges the traditional concept of cinema and operates outside mainstream structures in order to deconstruct and replace classical styles and conventions. -

My Mother's Daughter Monica Vanessa Martinez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2013-01-01 My Mother's Daughter Monica Vanessa Martinez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Chicana/o Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Monica Vanessa, "My Mother's Daughter" (2013). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1877. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1877 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY MOTHER’S DAUGHTER MONICA VANESSA MARTINEZ Department of Creative Writing APPROVED: Lex Williford, Chair Daniel Chacon Maryse Jayasuriya, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Monica Vanessa Martinez 2013 Dedication To my mother, Irma Martinez Montelongo. I will forever be my mother’s daughter, and that is a good thing. To Alejandro Montelongo, my ever present, and more importantly, ever supportive dad. To my darling sister, Marissa Montelongo. And finally, to la familia: your love and support are the best gifts I have ever been given because they gave me the courage to put my words out into the world. MY MOTHER’S DAUGHTER by MONICA VANESSA MARTINEZ, BA THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................