The Social Effects of Native Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story Jessica K Weir

The legal outcomes the Gunditjmara achieved in the 1980s are often overlooked in the history of land rights and native title in Australia. The High Court Onus v Alcoa case and the subsequent settlement negotiated with the State of Victoria, sit alongside other well known bench marks in our land rights history, including the Gurindji strike (also known as the Wave Hill Walk-Off) and land claim that led to the development of land rights legislation in the Northern Territory. This publication links the experiences in the 1980s with the Gunditjmara’s present day recognition of native title, and considers the possibilities and limitations of native title within the broader context of land justice. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR Euphemia Day, Johnny Lovett and Amy Williams filming at Cape Jessica Weir together at the native title Bridgewater consent determination Amy Williams is an aspiring young Jessica Weir is a human geographer Indigenous film maker and the focused on ecological and social communications officer for the issues in Australia, particularly water, NTRU. Amy has recently graduated country and ecological life. Jessica with her Advanced Diploma of completed this project as part of her Media Production, and is developing Research Fellowship in the Native Title and maintaining communication Research Unit (NTRU) at the Australian strategies for the NTRU. Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story JESSICA K WEIR First published in 2009 by the Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies GPO Box 553 Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6249 7714 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/ Written by Jessica K Weir Copyright © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. -

Constitutional Recognition Relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1

Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1 Attachment 1 - Timeline and Overview of findings Australian Human Rights Commission Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples – July 2018 Event Summary of event / response of Social Justice Commissioner 1991 The Royal Commission Both reports state an ongoing historical connection between past racist into Aboriginal Deaths in policies and legislation and current systemic discrimination and intersecting Custody (RCIADIC) issues of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander releases its report peoples. Human Rights and Equal NIRV states that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience an Opportunity Commission's endemic racism, causing serious racial violence associated with structural (HREOC) National Inquiry discrimination across Australian society. into Racist Violence (NIRV) releases its report The RCIADIC puts forward 339 recommendations. This includes developing pathways to achieving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self- determination, and the critical need to progress reconciliation to achieve the systemic changes recommended in the report.1 The Council of Aboriginal The Act states that CAR has been established because: Reconciliation (CAR) is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples occupied Australia before established under the British settlement at Sydney Cove -

Kimberley Land Council Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry Into the Native Title Act: Issues Paper 45 General Comment

Kimberley Land Council Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry into the Native Title Act: Issues Paper 45 General comment The Kimberley Land Council (KLC) is the native title representative body for the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The KLC is also a grass roots community organisation which has represented the interests of Kimberley Traditional Owners in their struggle for recognition of ownership of country since 1978. The KLC is cognisant of the limitations of the Native Title Act (NTA) in addressing the wrongs of the past and providing a clear pathway to economic, social and cultural independence for Aboriginal people in the future. The KLC strongly supports the review of the NTA by the Australian Law Reform Commission (Review) in the hope that it might provide an increased capacity for the NTA to address both past wrongs and the future needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The dispossession of country which occurred as a result of colonisation has had a profound and long lasting impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Country (land and sea) is centrally important to the cultural, social and familial lives of Aboriginal people, and its dispossession has had profound and continuing intergenerational effects. However, interests in land (and waters) is also a primary economic asset and its dispossession from Traditional Owners has prevented them from enjoying the benefits of its utilisation for economic purposes, and bestowed those benefits on others (in particular, in the Kimberley, pastoral, mining and tourism interests). The role of the NTA is to provide one mechanism for the original dispossession of country to be addressed, albeit imperfectly and subject to competing interests. -

Native Title Act 1993

Legal Compliance Education and Awareness Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) How does the Act apply to the University? • On occasion, the University assists with Native Title claims, by undertaking research & producing reports • Work is undertaken in conjunction with ARI, Native Title representative bodies & claims groups • Representative bodies define the University’s obligations & responsibilities with respect to Intellectual Property, ethics, confidentiality & cultural respect • While these obligations are contractual, as opposed to legislative, the University would be prudent to have an understanding of the Native Title Act, how a determination of Native Title is made & the role that the Federal Court has in the management of all applications made under the Act University of Adelaide 2 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Pre -colonisation • Aboriginal people & Torres Strait Islanders occupied Australia for at least 40,000 to 60,000 years before the first British colony was established in Australia • Traditional laws & customs were characterised by a strong spiritual connection to 'country' & covered things like: – caring for the natural environment and for places of significance – performing ceremonies & rituals – collecting food by hunting, fishing & gathering – providing education & passing on law & custom through stories, art, song & dance • In 1788 the British claimed sovereignty over part of Australia & established a colony University of Adelaide 3 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Post-colonisation • In 1889, the British courts applied the doctrine of terra nullius to Australia, finding that as a territory that was “practically unoccupied” • In 1979, the High Court of Australia determined that Australia was indeed a territory which, “by European standards, had no civilised inhabitants or settled law” 1992 – The Mabo decision • The Mabo v Queensland (No. -

The Boomerang Effect. the Aboriginal Arts of Australia 19 May - 7 January 2018 Preview 18 May 2017 at 6Pm

MEG Musée d’ethnographie de Genève Press 4 may 2017 The Boomerang Effect. The Aboriginal Arts of Australia 19 May - 7 January 2018 Preview 18 May 2017 at 6pm White walls, neon writing, clean lines: the MEG’s new exhibition «The Boomerang Effect. The Aboriginal Arts of Australia» welcomes its visitors in a space evocative of a contemporary art gallery. Here the MEG unveils one of its finest collections and reveals the wealth of indigenous Australia's cultural heritage. Visiting this exhibition, we understand how attempts to suppress Aboriginal culture since the 18th century have ended up having the opposite of their desired effect. When James Cook landed in Australia, in 1770, he declared the country to be «no one’s land» (terra nullius), as he recognized no state authority there. This justified the island's colonization and the limitless spoliation of its inhabitants, a medley of peoples who had lived there for 60,000 years, societies which up until today have maintained a visible and invisible link with the land through a vision of the world known as the Dreaming or Dreamtime. These mythological tales recount the creation of the universe as well as the balanced and harmonious relation between all the beings inhabiting it. It is told that, in ancestral times, the Djan’kawu sisters peopled the land by naming the beings and places and then lying down near the roots of a pandanus tree to give birth to sacred objects. It is related that the Dätiwuy clan and its land was made by a shark called Mäna. -

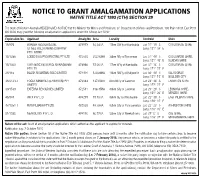

Notice to Grant Amalgamation Applications 5

attendance and improve peer relationships • Engage with families of young people involved in workshops • Maintain statistical records and data on service delivery Applications can be lodged online at • Program runs for up to 12 months Applications Now Open liveandworkhnehealth.com.au/work/ POSITION VACANT Desirable Criteria: Apply now to be part of the exciting first NSW Public opportunities-for-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-people/ • Ability to connect and engage with young Application Information Packages are available Aboriginal and Torres Strait Service Talent Pools. people at this web address or by contacting Islander Workshop Successfully applying for a talent pool is a great way to the application kit line on (02) 4985 3150. • Experience in conducting workshops namely in be considered for a large number of roles across the Facilitator school settings • Recognised tertiary qualifications in working NSW Public Service by submitting only one application. Ward Clerk Part-Time (3 days a week, 6 hours a day) The role: with young people Administrative Support Officer Muswellbrook • Skills in delivering innovative and artistic • To provide cultural workshops with one other – Open 16 to 29 September 2015 Enquires: Dianne Prangley, (02) 6542 2042 workshops through diverse cultural and artistic Policy Officer facilitator in local schools (Mt Druitt) expression Reference ID: 279881 • Workshops aim are to engage with students – Open 28 September to 12 October 2015 To apply please send your resume by Sunday 20th Applications may close early should 500 applications and improve identification with Aboriginal Closing Date: 14 October 2015 September to: [email protected] phone Julie be received culture; involve young people in NAIDOC week celebrations, increase school retention Dubuc on 0404 087 416. -

Karajarri Literature Review 2014

Tukujana Nganyjurrukura Ngurra All of us looking after country together Literature Review for Terrestrial & Marine Environments on Karajarri Land and Sea Country Compiled by Tim Willing 2014 Acknowledgements The following individuals are thanked for assistance in the DISCLAIMERS compilation of this report: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the Karajarri Rangers and Co-ordinator Thomas King; author and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the Kimberley Land Council’s Land and Sea Management unit. While reasonable Members of the Karajarri Traditional Lands Association efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication (KTLA) and IPA Cultural Advisory Committee: Joseph Edgar, are factually correct, the Land and Sea Management Unit accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents. To the Mervyn Mulardy Jnr, Joe Munro, Geraldine George, Jaqueline extent permitted by law, the Kimberley Land Council excludes all liability Shovellor, Anna Dwyer, Alma Bin Rashid, Faye Dean, Frankie to any person for any consequences, including, but not limited to all Shovellor, Lenny Hopiga, Shirley Spratt, Sylvia Shovellor, losses, damages, costs, expenses, and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and Celia Bennett, Wittidong Mulardy, Jessica Bangu and Rosie any information or material contained in it. Munro. This report contains cultural and intellectual property belonging to the Richard Meister from the KLC Land and Sea Management Karajarri Traditional Lands Association. Users are accordingly cautioned Unit, for coordination, meeting and editorial support as well to seek formal permission before reproducing any material from this report. -

Review of the Native Title Act 1993

Review of the Native Title Act 1993 DISCUSSION PAPER You are invited to provide a submission or comment on this Discussion Paper Discussion Paper 82 (DP 82) October 2014 This Discussion Paper reflects the law as at 1st October 2014 The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) was established on 1 January 1975 by the Law Reform Commission Act 1973 (Cth) and reconstituted by the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The office of the ALRC is at Level 40 MLC Centre, 19 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 Australia. Postal Address: GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: within Australia (02) 8238 6333 International: +61 2 8238 6333 Facsimile: within Australia (02) 8238 6363 International: +61 2 8238 6363 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.alrc.gov.au ALRC publications are available to view or download free of charge on the ALRC website: www.alrc.gov.au/publications. If you require assistance, please contact the ALRC. ISBN: 978-0-9924069-6-7 Commission Reference: ALRC Discussion Paper 82, 2014 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Requests for further authorisation should be directed to the ALRC. Making a submission Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission. The Australian Law Reform Commission seeks submissions from a broad cross-section of the community, as well as from those with a special interest in a particular inquiry. -

Introduction to NSW Planning Laws

1 Using the law to protect Aboriginal culture and heritage: culture and heritage: Consultation The NSW Government released a new policy in April relating to Aboriginal culture and heritage. 2010 outlining the consultation that must be However, the recent amendments to the NPW Act undertaken with Aboriginal communities before a and the NPW Regulations have created clear steps permit authorising damage or destruction to an and requirements to consult with Aboriginal people ‘Aboriginal object’ or’ Aboriginal Place’ is issued. before a permit is issued. These steps reflect those in the OEH Consultation Requirements policy. This Fact Sheet provides an overview of the policy – the Aboriginal cultural heritage consultation This fact sheet summarises the requirements for proponents 2010 (the Consultation Requirements policy) - and the stages of the consultation process relevant sections of the National Parks and Wildlife that must be followed, before OEH Regulation (the NPW Regulation). issues a permit, and how the As of 1 October 2010, key parts of the Consultation Aboriginal community can have a Requirements have been included in the NPW say at each stage. Regulation making consultation a legislative requirement in many cases. Do Aboriginal people have a right to be consulted about all developments? This is one of a series of Culture and Heritage Fact Sheets which have been developed for Local No. Whether consultation is required will depend Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) and the Aboriginal on the type of development and which laws apply. community by the NSW Aboriginal Land Council The National Parks and Wildlife Act does not always (NSWALC). apply, even if Aboriginal heritage is to be disturbed. -

Newsletter May Contain Images of Deceased People Looking Back on the KLC

KIMBERLEY LAND COUNCIL APRIL 2018 • GETTING BACK COUNTRY • CARING FOR COUNTRY • SECURING THE FUTURE PO Box 2145 | Broome WA 6725 | Ph: (08) 9194 0100 | Fax: (08) 9193 6279 | www.klc.org.au KIMBERLEY LAND COUNCIL CELEBRATES 40 YEARS Photo: Michael Gallagher WALKING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE This year we celebrate 40 years since the Kimberley Land Council was formed. In our fortieth year we are as strong as ever. Kimberley Aboriginal people still stand together as one mob, with one voice. Since 1978 there have been challenges and triumphs. From the pivotal days of Noonkanbah to the present we have been walking the long road to justice. It is this drive to improve the lives of the Kimberley mob and fight for what is rightfully ours that makes the KLC what it is today. Read more on page 13. Aboriginal people are warned that this newsletter may contain images of deceased people Looking back on the KLC DICKY SKINNER ADDRESSES TOM LYON PHOTOS: MICHAEL GALLAGHER 1978 - 40 years ago 1998 - 20 years ago The locked gates of Heritage under threat Noonkanbah The Federal Government has introduced a Bill into Parliament outlining the Unpublished letter to the editor of changes to the Aboriginal and Torres the West Australian Newspaper from Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act. If Yungngora Community, Noonkanbah the changes go through it will mean that Station Aboriginal people will depend on state laws to protect culture and heritage. It The government said we will benefit from will be very hard to get protection from this mining. How can we if our people’s the Federal Government, such as the lives are in danger from our people and protection given in 1994 to a special spirits? The white man does not believe Yawuru place under threat from a our story, or tribal law. -

ABORIGINAL and TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER HERITAGE PROTECTION ACT 1984 Reprinted As at 28 February 1991 TABLE of PROVISIONS

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- :,~~~~;~~~~~~#i~f~~f~~~~#:~~~~~r;~{~S:f]~!,i~i'~~j1*i~fcommercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws~{jgf¥~:t~~~%~~~~~~~;1'; Database as the source (© UNESCO). _"," : -J~~"'-_:-'-::"" :;. ..;.:. _ • ".'" ••.•... .:.- .. :-~ _.~. ,', .,.,..:-. : _~ ••..-. -,:." '. ; .....!:' '~:" ':. .:- _. , \ ; : ;: .\ ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER HERITAGE PROTECTION ACT 1984 Reprinted as at 28 February 1991 TABLE OF PROVISIONS ' . '". ..; Section PART I-PRELIMINARY 1. Short lille 2. Commencement 3. Interpretation 4. Purposes of Act 5, Extension to Territories 6. Act binds the Crown 7. Application of other laws 8. Application of Act SA. Application of Part II to Victoria PART II-PROTECTION OF SIGNIFICANT ABORIGINAL AREAS AND OBJECTS Division 1-Declarations by Minister Emergency daclarations in relation to areas Other declarations in relation to areas Contents of declarations under section 9 or 10 Declarations in relalion to objects Making 01 declarations Publication and commencement oj declarations Declarations reviewable by Parliament Refusal to make declaration Division 2-Dec/arations by Authorized Officers Authorised oHicers Emergency declarations in relation to areas or objects Notification 01 declarations Division 3-Discovery and Disposal of Aboriginal Remains Discovery of Aboriginal remains Disposal of Aboriginal remains (P.RA 7/91)-Cal. No. 91 4626 S --_._.- ----. DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. -

Sea Countries of the North-West: Literature Review on Indigenous

SEA COUNTRIES OF THE NORTH-WEST Literature review on Indigenous connection to and uses of the North West Marine Region Prepared by Dr Dermot Smyth Smyth and Bahrdt Consultants For the National Oceans Office Branch, Marine Division, Australian Government Department of the Environment and Water Resources * July 2007 * The title of the Department was changed to Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts in late 2007. SEA COUNTRIES OF THE NORTH-WEST © Commonwealth of Australia 2007. This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts or the Minister for Climate Change and Water. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication.