The Land Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Recognition Relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1

Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1 Attachment 1 - Timeline and Overview of findings Australian Human Rights Commission Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples – July 2018 Event Summary of event / response of Social Justice Commissioner 1991 The Royal Commission Both reports state an ongoing historical connection between past racist into Aboriginal Deaths in policies and legislation and current systemic discrimination and intersecting Custody (RCIADIC) issues of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander releases its report peoples. Human Rights and Equal NIRV states that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience an Opportunity Commission's endemic racism, causing serious racial violence associated with structural (HREOC) National Inquiry discrimination across Australian society. into Racist Violence (NIRV) releases its report The RCIADIC puts forward 339 recommendations. This includes developing pathways to achieving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self- determination, and the critical need to progress reconciliation to achieve the systemic changes recommended in the report.1 The Council of Aboriginal The Act states that CAR has been established because: Reconciliation (CAR) is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples occupied Australia before established under the British settlement at Sydney Cove -

Native Title Act 1993

Legal Compliance Education and Awareness Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) How does the Act apply to the University? • On occasion, the University assists with Native Title claims, by undertaking research & producing reports • Work is undertaken in conjunction with ARI, Native Title representative bodies & claims groups • Representative bodies define the University’s obligations & responsibilities with respect to Intellectual Property, ethics, confidentiality & cultural respect • While these obligations are contractual, as opposed to legislative, the University would be prudent to have an understanding of the Native Title Act, how a determination of Native Title is made & the role that the Federal Court has in the management of all applications made under the Act University of Adelaide 2 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Pre -colonisation • Aboriginal people & Torres Strait Islanders occupied Australia for at least 40,000 to 60,000 years before the first British colony was established in Australia • Traditional laws & customs were characterised by a strong spiritual connection to 'country' & covered things like: – caring for the natural environment and for places of significance – performing ceremonies & rituals – collecting food by hunting, fishing & gathering – providing education & passing on law & custom through stories, art, song & dance • In 1788 the British claimed sovereignty over part of Australia & established a colony University of Adelaide 3 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Post-colonisation • In 1889, the British courts applied the doctrine of terra nullius to Australia, finding that as a territory that was “practically unoccupied” • In 1979, the High Court of Australia determined that Australia was indeed a territory which, “by European standards, had no civilised inhabitants or settled law” 1992 – The Mabo decision • The Mabo v Queensland (No. -

Nhulunbuy Itinerary

nd 2 OECD Meeting of Mining Regions and Cities DarwinDarwin -– Nhulunbuy Nhulunbuy 23 – 24 November 2018 Nhulunbuy Itinerary P a g e | 2 DAY ONE: Friday 23 November 2018 Morning Tour (Approx. 9am – 12pm) 1. Board Room discussions - visions for future, land tenure & other Join Gumatj CEO and other guests for an open discussion surrounding future projects and vision and land tenure. 2. Gulkula Bauxite mining operation A wholly owned subsidiary of Gumatj Corporation Ltd, the Gulkula Mine is located on the Dhupuma Plateau in North East Arnhem Land. The small- scale bauxite operation aims to deliver sustainable economic benefits to the local Yolngu people and provide on the job training to build careers in the mining industry. It is the first Indigenous owned and operated bauxite mine. 3. Gulkula Regional Training Centre & Garma Festival The Gulkula Regional training is adjacent to the mine and provides young Yolngu men and women training across a wide range of industry sectors. These include; extraction (mining), civil construction, building construction, hospitality and administration. This is also where Garma Festival is hosted partnering with Yothu Yindi Foundation. 4. Space Base The Arnhem Space Centre will be Australia’s first commercial spaceport. It will include multiple launch sites using a variety of launch vehicles to provide sub-orbital and orbital access to space for commercial, research and government organisations. 11:30 – 12pm Lunch at Gumatj Knowledge Centre 5. Gumatj Timber mill The Timber mill sources stringy bark eucalyptus trees to make strong timber roof trusses and decking. They also make beautiful furniture, homewares and cultural instruments. -

Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

arts Article Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA Marie Geissler Faculty of Law Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; [email protected] Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA. Keywords: Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US. One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. -

HOMELAND STORY Saving Country

ROGUE PRODUCTIONS & DONYDJI HOMELAND presents HOMELAND STORY Saving Country PRESS KIT Running Time: 86 mins ROGUE PRODUCTIONS PTY LTD - Contact David Rapsey - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 Glenda Hambly - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 93867 2508 Mob: +61 457 078 513461 RONIN FILMS - Sales enquiries PO box 680, Mitchell ACT 2911, Australia Ph: 02 6248 0851 Fax: 02 6249 1640 [email protected] Rogue Productions Pty Ltd 104 Melville Rd, West Brunswick Victoria 3055 Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopses .............................................................................................. 3 Donydji Homeland History ................................................................. 4-6 About the Production ......................................................................... 7-8 Director’s Statement ............................................................................. 9 Comments: Damien Guyula, Yolngu Producer… ................................ 10 Comments: Robert McGuirk, Rotary Club. ..................................... 11-12 Comments: Dr Neville White, Anthropologist ................................. 13-14 Principal Cast ................................................................................. 15-18 Homeland Story Crew ......................................................................... 19 About the Filmmakers ..................................................................... 20-22 2 SYNOPSES ONE LINE SYNOPSIS An intimate portrait, fifty -

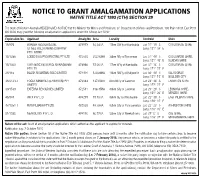

Notice to Grant Amalgamation Applications 5

attendance and improve peer relationships • Engage with families of young people involved in workshops • Maintain statistical records and data on service delivery Applications can be lodged online at • Program runs for up to 12 months Applications Now Open liveandworkhnehealth.com.au/work/ POSITION VACANT Desirable Criteria: Apply now to be part of the exciting first NSW Public opportunities-for-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-people/ • Ability to connect and engage with young Application Information Packages are available Aboriginal and Torres Strait Service Talent Pools. people at this web address or by contacting Islander Workshop Successfully applying for a talent pool is a great way to the application kit line on (02) 4985 3150. • Experience in conducting workshops namely in be considered for a large number of roles across the Facilitator school settings • Recognised tertiary qualifications in working NSW Public Service by submitting only one application. Ward Clerk Part-Time (3 days a week, 6 hours a day) The role: with young people Administrative Support Officer Muswellbrook • Skills in delivering innovative and artistic • To provide cultural workshops with one other – Open 16 to 29 September 2015 Enquires: Dianne Prangley, (02) 6542 2042 workshops through diverse cultural and artistic Policy Officer facilitator in local schools (Mt Druitt) expression Reference ID: 279881 • Workshops aim are to engage with students – Open 28 September to 12 October 2015 To apply please send your resume by Sunday 20th Applications may close early should 500 applications and improve identification with Aboriginal Closing Date: 14 October 2015 September to: [email protected] phone Julie be received culture; involve young people in NAIDOC week celebrations, increase school retention Dubuc on 0404 087 416. -

Witnessing the Apology

PHOTOGRAPHIC Essay Witnessing the Apology Juno gemes Photographer, Hawkesbury River I drove to Canberra alight with anticipation. ry, the more uncomfortable they became — not The stony-hearted policies of the past 11 years with me and this work I was committed to — but had been hard: seeing Indigenous organisations with themselves. I had long argued that every whose births I had witnessed being knee-capped, nation, including Australia, has a conflict history. taken over, mainstreamed; the painful ‘histori- Knowing can be painful, though not as painful as cal denialism’ (Manne 2008:27). Those gains memory itself. lost at the behest of Howard’s basically assimila- En route to Canberra, I stopped in Berrima tionist agenda. Yet my exhibition Proof: Portraits — since my schooldays, a weathervane of the from the Movement 1978–2003 toured around colonial mind. Here apprehension was evident. the country from the National Portrait Gallery in The woman working in a fine shop said to me, Canberra in 2003 to 11 venues across four States ‘I don’t know about this Apology’. She recounted and two countries, finishing up at the Museum of how her husband’s grandfather had fallen in love Sydney in 2008, and proved to be a rallying point with an Aboriginal woman and been turfed out for those for whom the Reconciliation agenda of his family in disgrace. Pain shadowed so many would never go away. For those growing pockets hearts in how many families across the nation? of resistance that could not be extinguished. ‘You might discover something for you in this’, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s new Labor Gov- I replied. -

Alycia Ashcroft 1 Page Suggestions for New Electorate Name

Suggestion 37 Alycia Ashcroft 1 page Suggestions for new electorate name: 1. Eleanor Harding 1934 – 1996 a. Equal rights and education campaigner Eleanor Harding was a respected community figure who poured her energy into achieving a better deal for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She was especially passionate about women's issues and education. Eleanor was a member of the Aborigines Advancement League and the Victorian branch of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) in the 1960s. During this time she worked on a national campaign to ensure equal rights for Indigenous Australians. She is also known for her work in pushing for improving Indigenous Australians rights through constitutional change. The 1967 Referendum on the Constitution ensued. As an executive member of the National Aboriginal and Islander Women's Council, Eleanor was part of women's rights advocacy group that protested against the Bicentennial celebrations in 1970 in Sydney and the women’s contingent that travelled to Canberra in support of the 1972 Aboriginal Tent Embassy protest. 2. Faith Bandler, AC 1918 -2015 a. Faith Bandler played an important role in establishing the civil rights movement in Australia and dedicated her life to equality and fairness for Indigenous Australians. Faith Bandler, AC, was a remarkable woman who was passionate in campaigning for the rights of Indigenous Australians and South Sea Islanders. 3. Pearl Gibbs 1901 – 1983 a. Pearl Gibbs was one of the most prominent female Indigenous female activists within the Aboriginal movement in the early 20th century. As a member of the Aborigines Progressive Association, she was involved with various protest events such as the 1938 Day of Mourning. -

Aboriginal Art - Resistance and Dialogue

University of New South Wales College of Fine Arts School of Art Theory ABORIGINAL ART - RESISTANCE AND DIALOGUE The Political Nature and Agency of Aboriginal Art A thesis submitted by Lee-Anne Hall in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art Theory CFATH709.94/HAL/l Ill' THE lJNIVERSllY OF NEW SOUTH WALES COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Thesis/Project Report Sheet Surnune or Funily .nune· .. HALL .......................................................................................................................................................-....... -............ · · .... U · · MA (TH' rn ....................................... AbbFinlname: . ·......... ' ....d ........... LEE:::ANNE ......................lend.............. ................. Oher name/1: ..... .DEBaaAH. ....................................- ........................ -....................... .. ,CVlalJOn, or C<ltal &1YCOIn '"" NVCfllt)'ca It:.... ..................... ( ............................................ School:. .. ART-����I��· ...THEORY ....... ...............................··N:t�;;�?A�c·���JlacjTn·ar··................................... Faculty: ... COLLEGE ... OF. ...·Xr"t F.J:blll:...................... .AR'J: ..................... .........................-........................ n,1e:........ .................... •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• .. •••••• .. •••••••••••••••••••••••••• .. •• • .. ••••• .. ••••••••••• ..••••••• .................... H ................................................................ -000000000000••o00000000 -

Yolŋu Information Sharing and Clarity of Understanding

Yolŋu Information sharing and clarity of understanding 1. Introduction This project Yolŋu Information sharing and clarity of understanding is stage 1 of a programme proposed by Motivation Australia consisting of 5 stages called Inclusive Community Development in East Arnhem Land. Five community visits to carry out Discovery Education sessions were carried out in Ramingining, Milingimbi, Galiwin'ku, Gapuwiyak1 and Darwin, and a workshop was held in Darwin in the first half of 2013. This project was carried out with the Aboriginal Resource and Development Services Inc. (ARDS) and funded by the FaHCSIA Practical Design Fund. Content This is the final project report with appendices detailing all of the content discussed during the five community visits to carry out Discovery Education sessions. The content is as follows: 2. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 3. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 7 5. Report ............................................................................................................................................. 8 6. An introduction to Yolŋu culture; as it relates to disability issues ................................................... 8 7. Issues for -

Gove Transition Project

C O N V E N E S P R E S E N T S C O O R D I N A T E S O R G A N I Z E S C O L L A B O R A T E S M E D I A P A R T N E R “First Meeting of the Network of Mining Regions” TRANSITIONING REGIONAL ECONOMIES IN ARNHEM LAND Jim Rogers Regional Executive Director 33,000 풌풎풔 East Arnhem Region Population 16,000 (70% Indigenous) Rio Tinto Bauxite and Alumina Ranger Uranium Mine GEMCO Manganese Nhulunbuy • Township built by Nabalco in late 1960s – early 1970s • Purpose: to support bauxite mining operation and associated refinery • Resident numbers b/n 3000 and 5000 people, nearly all mining related, non-Indigenous and highly transient • The mining titles are linked directly to the township Special Purposes lease – finite • Well serviced regional centre with a capable airport, sea port and other community infrastructure East Arnhem and Gove Peninsula transition A 10-15 Year Plan 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 Ongoing Gove Transition (4years) - Growth and diversification – ~10 years Closure planning and post mining economy – ~10+ years – GOVE TRANSITION: NOVEMBER 2013 “In the end, gas wasn’t enough. It will take 8 months to wind down operations at the refinery. The workforce will reduce from 1450 to 350 people ” Rio Tinto Alcan Transition Director COMMUNITY AND BUSINESS RESPONSE RESPONSE: NT GOVE TRANSITION TEAM On Ground Senior Transition Manager NT Government Dedicated multi-agency project team Working directly with Rio Tinto leadership and Transition Team Darwin Senior Executive Leadership CEs Steering Group Policy and program support -

A Reflection on the First 30 Days of the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy

A REFLECTION ON THE FIRST THIRTY DAYS OF THE EMBASSY By Gary Foley From the book: Foley, G, Schaap, A & Howell, E 2013, The Aboriginal Tent Embassy. [electronic resource] : Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State, Hoboken : Taylor and Francis, 2013 It was in the first four weeks of the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy protest that a small group of Aboriginal activists rapidly improvised and transformed an opportunistic accident into an effective protest that captured world attention and brought significant historical and political change in Australia.1 What had begun as a simple knee-jerk reaction to an Australia Day statement on Land Rights by the Australian Prime Minister, resulted in the accidental discovery that there was no law in Canberra that prevented the activists from staging a protest camp on the lawns of Parliament. The swift action of the activists to take advantage of this situation enabled them to gain political advantage over the McMahon Government in the propaganda war and political battle that would take place over the next six months. Exactly how these events unfolded has never been written about in detail. Even in Scott Robinson’s (ch.1 in this volume) or in Kathy Lothian’s (2007) accounts, the crucial early days are not fully examined. Yet if we are to gain a better understanding of why the Aboriginal Embassy was able to become such an effective protest action, it is important to gain an awareness of how it all began. So in this chapter I will examine some of the factors that enabled the already highly effective group of Aboriginal activists from the Redfern Black Power collective to create a highly effective challenge to the political power structure and force a major change in policy.