HOMELAND STORY Saving Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

Savanna Responses to Feral Buffalo in Kakadu National Park, Australia

Ecological Monographs, 77(3), 2007, pp. 441–463 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America SAVANNA RESPONSES TO FERAL BUFFALO IN KAKADU NATIONAL PARK, AUSTRALIA 1,2,6 3,4,5 5 4,5 5 AARON M. PETTY, PATRICIA A. WERNER, CAROLINE E. R. LEHMANN, JAN E. RILEY, DANIEL S. BANFAI, 4,5 AND LOUIS P. ELLIOTT 1Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California, Davis, California 95616 USA 2Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909 Australia 3The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 4Faculty of Education, Health and Science. Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 5School for Environmental Research, Charles Darwin University. Darwin, NT 0909, Australia Abstract. Savannas are the major biome of tropical regions, spanning 30% of the Earth’s land surface. Tree : grass ratios of savannas are inherently unstable and can be shifted easily by changes in fire, grazing, or climate. We synthesize the history and ecological impacts of the rapid expansion and eradication of an exotic large herbivore, the Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalus), on the mesic savannas of Kakadu National Park (KNP), a World Heritage Park located within the Alligator Rivers Region (ARR) of monsoonal north Australia. The study inverts the experience of the Serengeti savannas where grazing herds rapidly declined due to a rinderpest epidemic and then recovered upon disease control. Buffalo entered the ARR by the 1880s, but densities were low until the late 1950s when populations rapidly grew to carrying capacity within a decade. In the 1980s, numbers declined precipitously due to an eradication program. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

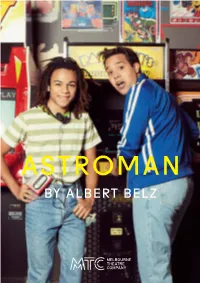

ASTROMAN by ALBERT BELZ Welcome

ASTROMAN BY ALBERT BELZ Welcome Over the course of this year our productions have taken you to London, New York, Norway, Malaysia and rural Western Australia. In Astroman we take you much closer to home – to suburban Geelong where it’s 1984. ASTROMAN In this touching and humorous love letter to the 80s, playwright Albert Belz wraps us in the highs and lows of growing up, the exhilaration of learning, and what it means to be truly courageous. BY ALBERT BELZ Directed by Sarah Goodes and Associate Director Tony Briggs, and performed by a cast of wonderful actors, some of them new to MTC, Astroman hits the bullseye of multigenerational appeal. If ever there was a show to introduce family and friends to theatre, and the joy of local stories on stage – this is it. At MTC we present the very best new works like Astroman alongside classics and international hits, from home and abroad, every year. As our audiences continue to grow – this year we reached a record number of subscribers – tickets are in high demand and many of our performances sell out. Subscriptions for our 2019 Season are now on sale and offer the best way to secure your seats and ensure you never miss out on that must-see show. To see what’s on stage next year and book your package visit mtc.com.au/2019. Thanks for joining us at the theatre. Enjoy Astroman. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

Asapentertainment

ASAPEntertainment Supplying Live Music and Entertainment po box 1170 Corporate & Conferences noosa heads qld 4567 Venues, Events & Functions ph 07 5449 2907 www.asapentertainment.com.au [email protected] m 0412 638 216 ARTIST 5104 They will lavish style upon your special occasion … They will strike the right note … simmering and soft at cocktail hour or crooning the night away with a nod to Sinatra. A trio with an extensive repertoire featuring nostalgic New Orleans jazz and contemporary love ballads along with burning, up-tempo be-bop. And later … they can light up your dance floor with party starters to move your groove … A versatile trio, they bring a huge repertoire to your event. They can ease into the night with specialist background music at dinner and then light-up the floor with your favorite rock, pop and dance tunes later. They have supported Bernard Fanning (Powderfinger) and Pete Murray at past functions and band members have played on bills with Bob Dylan, The Buena Vista Social Club, Gotye, Kanye West, Soundgarden, Arrested Development, Kimbra and Jimmy Barnes on stages around the world. Some of their satisfied clients include: The State Premier of Queensland The Lord Mayor of Brisbane Coca-Cola Amatil BHP Billiton The Mimiki Foundation … plus hundreds of successful weddings, functions and parties. Testimonials: Hi Joelle, the trio was very well received (and nice guys too) and I was asked for your contact details by several people. They read the crowd perfectly. Thank you for all your assistance and excellent customer service ... made my job so much easier! - Lisa, BusinessDepot “What can I say? The trio was amazing and gave the room that extra dimension that made it feel like a party. -

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Volume 18, Number 1 (2018) Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University Paul Linden, Associate Editor Butler University Ben O’Hara, Associate Editor (Book Reviews) Australian College of the Arts Published with Support from The Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators As- sociation (the MEIEA Journal) is published annually by MEIEA in order to increase public awareness of the music and entertainment industry and to foster music and entertainment business research and education. The MEIEA Journal provides a scholarly analysis of technological, legal, historical, educational, and business trends within the music and entertainment industries and is designed as a resource for anyone currently involved or interested in these industries. Topics include issues that affect music and entertainment industry education and the music and entertain- ment industry such as curriculum design, pedagogy, technological innova- tion, intellectual property matters, industry-related legislation, arts admin- istration, industry analysis, and historical perspectives. Ideas and opinions expressed in the Journal of the Music & Enter- tainment Industry Educators Association do not necessarily reflect those of MEIEA. MEIEA disclaims responsibility for statements of fact or opin- ions expressed in individual contributions. Permission for reprint or reproduction must be obtained in writing and the proper credit line given. Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association 1900 Belmont Boulevard Nashville, TN 37212 U.S.A. www.meiea.org The MEIEA Journal (ISSN: 1559-7334) © Copyright 2018 Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association All rights reserved Editorial Advisory Board Bruce Ronkin, Editor, Northeastern University Paul Linden, Associate Editor, Butler University Ben O’Hara, Associate Editor, Australian College of the Arts (Collarts) Timothy Channell, Radford University Mark J. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Yolŋu Information Sharing and Clarity of Understanding

Yolŋu Information sharing and clarity of understanding 1. Introduction This project Yolŋu Information sharing and clarity of understanding is stage 1 of a programme proposed by Motivation Australia consisting of 5 stages called Inclusive Community Development in East Arnhem Land. Five community visits to carry out Discovery Education sessions were carried out in Ramingining, Milingimbi, Galiwin'ku, Gapuwiyak1 and Darwin, and a workshop was held in Darwin in the first half of 2013. This project was carried out with the Aboriginal Resource and Development Services Inc. (ARDS) and funded by the FaHCSIA Practical Design Fund. Content This is the final project report with appendices detailing all of the content discussed during the five community visits to carry out Discovery Education sessions. The content is as follows: 2. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 3. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 7 5. Report ............................................................................................................................................. 8 6. An introduction to Yolŋu culture; as it relates to disability issues ................................................... 8 7. Issues for -

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION on the TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and Plants

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ON THE TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and plants Report prepared by John Woinarski, Kym Brennan, Ian Cowie, Raelee Kerrigan and Craig Hempel. Darwin, August 2003 Cover photo: Tall forests dominated by Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tetrodonta, Darwin woollybutt E. miniata and Melville Island Bloodwood Corymbia nesophila are the principal landscape element across the Tiwi islands (photo: Craig Hempel). i SUMMARY The Tiwi Islands comprise two of Australia’s largest offshore islands - Bathurst (with an area of 1693 km 2) and Melville (5788 km 2) Islands. These are Aboriginal lands lying about 20 km to the north of Darwin, Northern Territory. The islands are of generally low relief with relatively simple geological patterning. They have the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory (to about 2000 mm annual average rainfall in the far north-west of Melville and north of Bathurst). The human population of about 2000 people lives mainly in the three towns of Nguiu, Milakapati and Pirlangimpi. Tall forests dominated by Eucalyptus miniata, E. tetrodonta, and Corymbia nesophila cover about 75% of the island area. These include the best developed eucalypt forests in the Northern Territory. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 1300 rainforest patches, with floristic composition in many of these patches distinct from that of the Northern Territory mainland. Although the total extent of rainforest on the Tiwi Islands is small (around 160 km 2 ), at an NT level this makes up an unusually high proportion of the landscape and comprises between 6 and 15% of the total NT rainforest extent. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 200 km 2 of “treeless plains”, a vegetation type largely restricted to these islands. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF).