Bats and Zoonotic Viruses: Can We Confidently Link Bats with Emerging Deadly Viruses?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Cynopterus Minutus, Minute Fruit Bat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2019: T136423A21985433 Scope: Global Language: English Cynopterus minutus, Minute Fruit Bat Assessment by: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ruedas, L. & Suyanto, A. 2019. Cynopterus minutus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T136423A21985433. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019- 3.RLTS.T136423A21985433.en Copyright: © 2019 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Chiroptera Pteropodidae Taxon Name: Cynopterus minutus Miller, 1906 Common Name(s): • English: Minute Fruit Bat Taxonomic Notes: This may be a species complex. -

Genetic Diversity of the Chaerephon Leucogaster/Pumilus Complex From

Genetic diversity of the Chaerephon leucogaster/pumilus complex from mainland Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands Theshnie Naidoo 202513500 Submitted in fulfillment of the academic Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Life Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu – Natal, Durban. NOVEMBER 2013 Supervisory Committee Prof. JM. Lamb Dr. MC. Schoeman Dr. PJ. Taylor Dr. SM. Goodman i ABSTRACT Chaerephon (Dobson, 1874), an Old World genus belonging to the family Molossidae, is part of the suborder Vespertilioniformes. Members of this genus are distributed across mainland Africa (sample sites; Tanzania, Yemen, Kenya, Botswana, South Africa and Swaziland), its offshore islands (Zanzibar, Pemba and Mozambique Island), Madagascar and the surrounding western Indian Ocean islands (Anjouan, Mayotte, Moheli, Grande Comore, Aldabra and La Reunion). A multifaceted approach was used to elucidate the phylogenetic and population genetic relationships at varying levels amongst these different taxa. Working at the subspecific level, I analysed the phylogenetics and phylogeography of Chaerephon leucogaster from Madagascar, based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and control region sequences. Cytochrome b genetic distances among C. leucogaster samples were low (maximum 0.35 %). Genetic distances between C. leucogaster and C. atsinanana ranged from 1.77 % to 2.62 %. Together, phylogenetic and distance analyses supported the classification of C. leucogaster as a separate species. D-loop data for C. leucogaster samples revealed significant but shallow phylogeographic structuring into three latitudinal groups (13º S, 15 - 17º S, 22 - 23º S) showing exclusive haplotypes which correlated with regions of suitable habitat defined by ecological niche modelling. Population genetic analysis of D-loop sequences indicated that populations from Madagascar have been expanding since 5 842 - 11 143 years BP. -

Guide for Common Viral Diseases of Animals in Louisiana

Sampling and Testing Guide for Common Viral Diseases of Animals in Louisiana Please click on the species of interest: Cattle Deer and Small Ruminants The Louisiana Animal Swine Disease Diagnostic Horses Laboratory Dogs A service unit of the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine Adapted from Murphy, F.A., et al, Veterinary Virology, 3rd ed. Cats Academic Press, 1999. Compiled by Rob Poston Multi-species: Rabiesvirus DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 1 Cattle Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 2 Deer and Small Ruminants Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral disease Respiratory viral disease Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 3 Swine Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 4 Horses Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Neurological viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Abortifacient/neonatal viral diseases Viral infections affecting the skin Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. B2 5 Dogs Please click on the principle system involvement Generalized viral diseases Respiratory viral diseases Enteric viral diseases Reproductive/neonatal viral diseases Back to the Beginning DCN LADDL Guide for Common Viral Diseases v. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

African Bat Conservation News

Volume 35 African Bat Conservation News August 2014 ISSN 1812-1268 © ECJ Seamark, 2009 (AfricanBats) Above: A male Cape Serotine Bat (Neoromicia capensis) caught in the Chitabi area, Okavango Delta, Botswana. Inside this issue: Research and Conservation Activities Presence of paramyxo and coronaviruses in Limpopo caves, South Africa 2 Observations, Discussions and Updates Recent changes in African Bat Taxonomy (2013-2014). Part II 3 Voucher specimen details for Bakwo Fils et al. (2014) 4 African Chiroptera Report 2014 4 Scientific contributions Documented record of Triaenops menamena (Family Hipposideridae) in the Central Highlands of 6 Madagascar Download and subscribe to African Bat Conservation News published by AfricanBats at: www.africanbats.org The views and opinions expressed in articles are no necessarily those of the editor or publisher. Articles and news items appearing in African Bat Conservation News may be reprinted, provided the author’s and newsletter refer- ence are given. African Bat Conservation News August 2014 vol. 35 2 ISSN 1812-1268 Inside this issue Continued: Recent Literature Conferences 7 Published Books / Reports 7 Papers 7 Notice Board Conferences 13 Call for Contributions 13 Research and Conservation Activities Presence of paramyxo- and coronaviruses in Limpopo caves, South Africa By Carmen Fensham Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, 0001, Republic of South Africa. Correspondence: Prof. Wanda Markotter: [email protected] Carmen Fensham is a honours excrement are excised and used to isolate any viral RNA that student in the research group of may be present. The identity of the RNA is then determined Prof. -

Article/19/7/12-1820-Techapp1.Pdf)

LETTERS Novel Bat-borne (S)–segment primer set (outer: OS- found by RT-PCR that used XSV- M55F, 5′-TAGTAGTAGACTCC-3′, specific primers. Hantavirus, and XSV-S6R, 5′-AGITCIGGRTC- Phylogenetic analyses was per- Vietnam CATRTCRTCICC-3′; inner: Cro- formed with maximum-likelihood 2F, 5′-AGYCCIGTIATGRGW- and Bayesian methods, and we used To the Editor: Compelling evi- GTIRTYGG-3′, and JJUVS-1233R, the GTR+I+Γ model of evolution, dence of genetically distinct hantavi- 5′-TCACCMAGRTGRAAGTGRT- as selected by the hierarchical like- ruses (family Bunyaviridae) in multi- CIAC-3. The bat was captured dur- lihood-ratio test in MrModel-test ple species of shrews and moles (order ing July 2012 in Xuan Son National version 2.3 and jModelTest version Soricomorpha, families Soricidae and Park, a nature reserve in Thanh Sơn 0.1 (10), partitioned by codon po- Talpidae) across 4 continents (1–7) District, Phu Tho Province, ≈100 sition. Results indicated 4 distinct suggests that soricomorphs, rather km west of Hanoi (21°07′26.75′N, phylogroups, with XSV sharing a than rodents (order Rodentia, families 104°57′29.98′′E). common ancestry with MGBV (Fig- Muridae and Cricetidae), might be the For confirmation, RNA extrac- ure). Similar topologies, supported primordial hosts (6,7). Recently, the tion and RT-PCR were performed in- by high bootstrap (>70%) and poste- host range of hantaviruses has been dependently in a laboratory in which rior node (>0.70) probabilities, were further expanded by the discovery that hantaviruses had never been handled. consistently derived when various insectivorous bats (order Chiroptera) After initial detection, the L-segment algorithms and different taxa and also serve as reservoirs (8,9). -

Characterization of the Rubella Virus Nonstructural Protease Domain and Its Cleavage Site

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, July 1996, p. 4707–4713 Vol. 70, No. 7 0022-538X/96/$04.0010 Copyright q 1996, American Society for Microbiology Characterization of the Rubella Virus Nonstructural Protease Domain and Its Cleavage Site 1 2 2 1 JUN-PING CHEN, JAMES H. STRAUSS, ELLEN G. STRAUSS, AND TERYL K. FREY * Department of Biology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia 30303,1 and Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 911252 Received 27 October 1995/Accepted 3 April 1996 The region of the rubella virus nonstructural open reading frame that contains the papain-like cysteine protease domain and its cleavage site was expressed with a Sindbis virus vector. Cys-1151 has previously been shown to be required for the activity of the protease (L. D. Marr, C.-Y. Wang, and T. K. Frey, Virology 198:586–592, 1994). Here we show that His-1272 is also necessary for protease activity, consistent with the active site of the enzyme being composed of a catalytic dyad consisting of Cys-1151 and His-1272. By means of radiochemical amino acid sequencing, the site in the polyprotein cleaved by the nonstructural protease was found to follow Gly-1300 in the sequence Gly-1299–Gly-1300–Gly-1301. Mutagenesis studies demonstrated that change of Gly-1300 to alanine or valine abrogated cleavage. In contrast, Gly-1299 and Gly-1301 could be changed to alanine with retention of cleavage, but a change to valine abrogated cleavage. Coexpression of a construct that contains a cleavage site mutation (to serve as a protease) together with a construct that contains a protease mutation (to serve as a substrate) failed to reveal trans cleavage. -

Validation of the Easyscreen Flavivirus Dengue Alphavirus Detection Kit

RESEARCH ARTICLE Validation of the easyscreen flavivirus dengue alphavirus detection kit based on 3base amplification technology and its application to the 2016/17 Vanuatu dengue outbreak 1 1 1 2 2 Crystal Garae , Kalkoa Kalo , George Junior Pakoa , Rohan Baker , Phill IsaacsID , 2 Douglas Spencer MillarID * a1111111111 1 Vila Central Hospital, Port Vila, Vanuatu, 2 Genetic Signatures, Sydney, Australia a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Background OPEN ACCESS The family flaviviridae and alphaviridae contain a diverse group of pathogens that cause sig- Citation: Garae C, Kalo K, Pakoa GJ, Baker R, nificant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Diagnosis of the virus responsible for disease is Isaacs P, Millar DS (2020) Validation of the easyscreen flavivirus dengue alphavirus detection essential to ensure patients receive appropriate clinical management. Very few real-time kit based on 3base amplification technology and its RT-PCR based assays are able to detect the presence of all members of these families application to the 2016/17 Vanuatu dengue using a single primer and probe set. We have developed a novel chemistry, 3base, which outbreak. PLoS ONE 15(1): e0227550. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227550 simplifies the viral nucleic acids allowing the design of RT-PCR assays capable of pan-fam- ily identification. Editor: Abdallah M. Samy, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University (ASU), EGYPT Methodology/Principal finding Received: April 11, 2019 Synthetic constructs, viral nucleic acids, intact viral particles and characterised reference Accepted: December 16, 2019 materials were used to determine the specificity and sensitivity of the assays. Synthetic con- Published: January 17, 2020 structs demonstrated the sensitivities of the pan-flavivirus detection component were in the Copyright: © 2020 Garae et al. -

Bats of Nepal a Field Guide/ /Bats of Nepal a Field Guide

Bats of Nepal A field guide/ /Bats of Nepal A field guide This Publication is supported by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) - World Wildlife Fund WWF Nepal Designed and published by: Small Mammals Conservation and Research Foundation (SMCRF) Compiled and edited by: Pushpa Raj Acharya, Hari Adhikari, Sagar Dahal, Arjun Thapa and Sanjan Thapa Cover photographs: Front cover: Myotis sicarius Mandelli's Mouse-eared Myotis by Sanjan Thapa Back cover: Myotis csorbai Csorba's Mouse-eared Myotis by Sanjan Thapa Cover design: Rajesh Goit First edition 2010 500 copies ISBN 978-9937-2-2951-7 Copyright © 2010 all rights reserved at authors and SMCRF No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or copied in any form-printed, electronic and photocopied without the written Bats of Nepal permission from the publisher. A field guide Bats of Nepal A field guide/ /Bats of Nepal A field guide forts which strategically put their attention to bat research though we were less experienced and trained. Meanwhile, Bat researches were simultaneously PREFACE supported by international agencies: Bat Conservation International, Lubee Bat Conservancy, Rufford small grants and Chester Zoo. Inconsistent database advocates around 60 species of bat hosted to Nepalese land- scape. Our knowledge on bat fauna is merely based on opportunistic and rare A picture can speak thousand words, we have tried to include maximum pho- effort carried out by foreign scholars bounded with countries biological policy. tographs of the species (about 40 photographs); Most of the bat pictures used in Almost 40 years of biodiversity effort of Nepal, Small mammals has got no re- this book were clicked during different field studies in Nepal. -

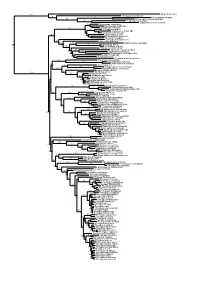

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae