Legitmate Military Objective Under the Current Jus in Bello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

11 April 2000 (Extract from Book 5)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 11 April 2000 (extract from Book 5) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor His Excellency the Honourable Sir JAMES AUGUSTINE GOBBO, AC The Lieutenant-Governor Professor ADRIENNE E. CLARKE, AO The Ministry Premier, Treasurer and Minister for Multicultural Affairs .............. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Health and Minister for Planning......... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Industrial Relations and Minister assisting the Minister for Workcover..................... The Hon. M. M. Gould, MLC Minister for Transport............................................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Energy and Resources, Minister for Ports and Minister assisting the Minister for State and Regional Development. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Minister for State and Regional Development, Minister for Finance and Assistant Treasurer............................................ The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Local Government, Minister for Workcover and Minister assisting the Minister for Transport regarding Roads........ The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. C. M. Campbell, MP Minister for Education and Minister for the Arts...................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Environment and Conservation and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections........................................ The Hon. A. Haermeyer, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs............ The Hon. K. G. Hamilton, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Manufacturing Industry and Minister for Racing............................................ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Minister for Post Compulsory Education, Training and Employment.... -

Issue No. 29 WESTLINK 5 November

Issue No. 29 WESTLINK 5 th November 2007 COMMITTEE 2007 – 2008 President: Fred BROWN Vice President: Mike VENN Secretary/Treasurer/Westlink Editor: Brian MEAD Committee Members: Brian FIRNS, Kim JOHNSTONE. Issue No 29 WESTLINK 5th November 2007 Page -_2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. From the President …………………………………. Page 3 2. Our Front Cover ……………………………………. Page 4 3. From the Editor …………………………………….. Page 4 4. Address by the GOVERNOR GENERAL ……. Page/s 5-7 5. Address by LTCOL Clem Sargent ....................... Page/s 8-9 6. THE RECEPTION …………………………………. Page 10 7. Reflections on the Dedication Ceremony ……… Page/s 11-12 8. ANZAC DAY 2007 ……………………………. ….. Page 13 9. IMAGES - ANNUAL RE-UNION DINNER / THE RAE WATERLOO DINNER ……………… Page 14 10. THE WESTON’S VISIT …………………….. ……. Page 15 11. THE PURPLE BERET …….…………..................... Page/s 16-18 12. BRIDGETOWN, WA – ANZAC DAY 2007 ….. Page/s 19-20 13. WARREN HALL – CITIZEN OF THE YEAR Page 21 14. TOODYAY, WA - ANZAC DAY 2007 …. ……. Page/s 22-23 15. DARWIN VISIT – AUGUST 2007 ………………. Page/s 24-27 16. ABOUT EMUS …….…………...................................... Page 28-30 17. MEMBERSHIP ……………….…….…………........... Page 31-32 Issue No 29 WESTLINK 5th November 2007 Page -_3 FROM THE PRESIDENT Greetings Fellow Members, Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the time and effort that our Hon Sec Brian Mead has put into the publication of this edition of Westlink. Brian has put many hours of soliciting, collecting, collating and editing items, even rebuilding his computer… Many thanks Brian! Whilst handing out bouquets, on behalf of our Association membership, I would like to congratulate Warren Hall on his nomination for Citizen of the Year in Toodyay. -

1962 Volume 054 01 June

THE PEGASUS THE JOURNAL OF THE GEELONG COLLEGE Vol. LV JUNE, 1962 S. J. MILES J. E. DAVIES Captain of School, 1962 Vice-Captain of School, 1962 D. J. LAIDLAW R. N. DOUGLAS Liet Prize for French, I960 Queen's Scholarship, 196' Ormond Scholarship, 1961 Proxime Accessit, 1961 Dux of College, 1961 JUNE, 1962. CONTENTS Page Council and Staff 4 Editorial 7 Speech Day 8 Principal's Report 8 School Prize Lists 14 Examination Results 16 Scholarships 17 Salvete 18 Valete 18 Sir Horace Robertson 21 School Diary 22 School Activities 24 Social Services 24 P.P. A 24 Morrison Library 25 Junior Clubs 25 Railway Society 26 Letter to the Editor 26 Pegasus Appeal 27 Sport 28 Cricket 28 Rowing 38 Swimming 40 Tennis 41 Original Contributions 43 Preparatory School 50 Old Boys 56 4 THE PEGASUS THE GEELONG COLLEGE COUNCIL Chairman: Sir Arthur Coles, K.B. D. S. Adam, Esq., LL.B. H. A. Anderson, Esq. A. Austin Gray, Esq. G. J. Betts, Esq. The Reverend M. J. Both. R. C. Dennis, Esq. P. N. Everist, Esq., B.Arch., A.R.A.I.A. F. M. Funston, Esq. The Reverend A. D. Hallam,, M.A., B.D. C. L. Hirst, Esq. The Hon. Sir Gordon McArthur, K.B., M.A, (Cantab.), M.L.C. P. McCallum, Esq., LL.B. E. W. McCann, Esq. F. E. Moreton, Esq., B.E.E., A.M.I.E. (Aust.). K. S. Nail, Esq. D. G. Neilson, Esq., F.C.A. Dr. H. N. Wettenhall, M.D, B.S., M.R.C.P., F.R.A.C.P. -

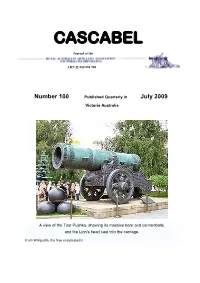

Issue100 – Jul 2009

CASCABEL Journal of the ABN 22 850 898 908 Number 100 Published Quarterly in July 2009 Victoria Australia A view of the Tsar Pushka, showing its massive bore and cannonballs, and the Lion's head cast into the carriage. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright . 3 The President Writes . 5 Membership Report . 6 Notice of Annual General Meeting 7 Editor‘s Scratchings 8 Rowell, Sir Sydney Fairbairn (1894 - 1975) 9 A Paper from the 2001 Chief of Army's Military History Conference 14 The Menin Gate Inauguration Ceremony - Sunday 24th July, 1927 23 2/ 8 Field Regiment . 25 HMAS Tobruk. 26 Major General Cyril Albert Clowes, CBE, DSO, MC 30 RAA Association(Vic) Inc Corp Shop. 31 Some Other Military Reflections . 32 Parade Card . 35 Changing your address? See cut-out proforma . 36 Current Postal Addresses All mail for the Association, except matters concerning Cascabel, should be addressed to: The Secretary RAA Association (Vic) Inc. 8 Alfada Street Caulfield South Vic. 3167 All mail for the Editor of Cascabel, including articles and letters submitted for publication, should be sent direct to . Alan Halbish 115 Kearney Drive Aspendale Gardens Vic 3195 (H) 9587 1676 [email protected] 2 CASCABEL Journal of the FOUNDED: CASCABLE - English spelling. ABN 22 850 898 908 First AGM April 1978 ARTILLERY USE: First Cascabel July 1983 After 1800 AD, it became adjustable. The COL COMMANDANT: breech is closed in large calibres by a BRIG N Graham CASCABEL(E) screw, which is a solid block of forged wrought iron, screwed into the PATRONS and VICE PATRONS: breach coil until it pressed against the end 1978 of the steel tube. -

Pegasus June 1960

The Pegasus THE JOURNAL OF THE GEELONG COLLEGE. Vol. LII. JUNE, 1960 No. 1 EDITORIAL PANEL. Editors: G. W. Young, Esq., B. G. Tymms, A. H. McArthur Sports Editors: J. S. Cox, G. R. A. Gregg, G. P. Hallebone, G. C. Fenton. Assistant Editors: P. M. McLennan, R. A. Both. Exchange Editors: R. J. Deans, G. J. Jamieson. Photography: R. N. Douglas, I. R. A. McLean, R, J. Schmidt. Committee: D. Aiton, D. E. Davies, I. J. Fairnie, I. R. Yule, R, J. Baker, D. G. Bent, A. L. Fletcher, A. R. Garrett, K. A. J. MacLean, J. S. Robson, M. A. Taylor, P. R. Mann Old Collegians: Messrs. B. R. Keith and D. G. Neilson. CONTENTS: Page Page Dr. M. A. Buntine 2 Cricket Notes 18 Editorial 4 The Sydney Trip 24 School Notes 5 Rowing Notes 32 Sir Arthur Coles 5 The Mildura Trip 36 The late Sir Horace Robertson 7 Tennis Notes 42 The Geelong College Centenary Building Swimming Notes 43 Fund 8 Original Contributions 46 The New Principal 9 Preparatory School Notes 49 Salvete and Valete 10 Opening of the New Preparatory School 50 Examination Results 13 Chairman's Address 50 House Notes 15 Mr. I. R. Watson 52 The Morrison Library 16 Preparatory School Sport 53 Cadet Notes 17 Old Boys' Notes 54 P.F.A. Notes 17 2 THE PEGASUS Dr. M. A. BUNTINE—A SCHOOL TRIBUTE. Dr. M. A. Buntine succeeded Rev. F. W. was achieved during his period as Prinicpal. An Rolland as Principal of the Geelong College in Exhibition was won in each of the last six 1946, as the School entered its 85th year. -

In from the Cold: Reflections on Australia's Korean

IN FROM THE COLD REFLECTIONS ON AUSTRALIA’S KOREAN WAR IN FROM THE COLD REFLECTIONS ON AUSTRALIA’S KOREAN WAR EDITED BY JOHN BLAXLAND, MICHAEL KELLY AND LIAM BREWIN HIGGINS Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760462727 ISBN (online): 9781760462734 WorldCat (print): 1140933889 WorldCat (online): 1140933931 DOI: 10.22459/IFTC.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: The story of a patrol 15 miles into enemy territory, c. 1951. Photographer: A. Gulliver. Source: Argus Newspaper Collection of Photographs, State Library of Victoria. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Acknowledgements . vii List of maps and figures . ix Maps . xiii Chronology . .. xix Contributors . xxvii Glossary . xxxiii Introduction . 1 John Blaxland Part 1. Politics by other means: Strategic aims and responses 1 . Setting a new paradigm in world order: The United Nations action in Korea . 29 Robert O’Neill 2 . The Korean War: Which one? When? . 49 Allan Millett 3 . China’s war for Korea: Geostrategic decisions, war-fighting experience and high-priced benefits from intervention, 1950–53 . 61 Xiaobing Li 4 . Fighting in the giants’ playground: Australians in the Korean War . 87 Cameron Forbes 5 . The transformation of the Republic of Korea Army: Wartime expansion and doctrine changes, 1951–53 . -

By Force of Arms: Rape, War, and Military Culture

Duke Law Journal VOLUME 45 FEBRUARY 1996 NUMBER 4 BY FORCE OF ARMS: RAPE, WAR, AND MILITARY CULTURE MADELINE MORRISt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCrION ............................... 652 I. RAPE BY MILrrARY PERSONNEL ................. 654 A. The Rape Differential .................... 656 1. The Peacetime Study ................. 659 2. The Wartime Study .................. 664 II. THE RAPE DIFFERENTIAL: CAUSES AND CULTURE . 674 A. Causes .. ........................... 674 B. The Rape Differential and Military Culture .... 691 1. Primary Groups .................... 691 2. Primary Groups in Military Organizations . 692 t Copyright © 1996 by Madeline Morris. Professor of Law, Duke University. I am grateful for the contributions of Kate Bartlett, Lawrence Baxter, Brian Belanger, Kenneth Bullock, Paul Carrington, Dennis DeConcini, Cynthia Enloe, Robinson Everett, William Fulton, John Gagnon, Pamela Gann, Tim Gearan, Shannon Geibsler, Andrew Gordon, Frangoise Hampson, Donald Horowitz, Susan Kerner-Hoeg, Benedict Kingsbury, Peter Klopfer, Andrew Koppelman, Paul Kurtz, David Lange, Charlene Lewis, Robert Lifton, Dino Lorenzini, Elizabeth McGoogan, Laura Miller, Mary Newcomer, Jonathan Ocko, Steven Prentice-Dunn, Horace Robertson, Alex Roland, Gladys Rothbell, Sheldon Rothbell, Mady Segal, Scott Silliman, Judith Stiehm, Olga Suhomlinova, Theodore Triebel, Laura Underkuffler, William Van Alstyne, Ronald Vergnoile, Neil Vidmar, Michael Wells, Yoshiaki Yoshimi, Chung-ok Yun, the participants at the April 1994 Colloquium of the Georgia Humanities Center, the participants at the May 27, 1993 meeting of the Feminist Discussion Group of Kyoto, and the participants at the 1993 Rockefeller Foundation Conference on Women and War. For methodological assistance, I am indebted to John Jarvis, Survey Statistician, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and to Kenneth Land, Chair, Department of Sociology, Duke University. -

Assault Brigade: the 18Th Infantry Brigade’S Development As an Assault Formation in the SWPA 1942-45

Assault Brigade: The 18th Infantry Brigade’s Development as an Assault Formation in the SWPA 1942-45 Matthew E. Miller A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences CANBERRA 1 February 2019 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I need to thank my wonderful wife Michelle who suffered the brunt of the long hours and research trips during this project. I would also like to thank my friends and colleagues Caleb Campbell, Tony Miller, Jason Van't Hof, Nathaniel Watson, and Jay Iannacito. All of whom, to include Michelle, have by way of my longwinded expositions, acquired involuntary knowledge of the campaigns of the South West Pacific. Thanks for your patience and invaluable insights. A special thanks to my advisors Professor Craig Stockings, Emeritus Professor Peter Dennis, and Associate Professor Eleanor Hancock. No single individual embarks on a research journey of this magnitude without a significant amount of mentorship and guidance. This effort has been no different. ii Acronyms AAMC Australian Army Medical Corps AAOC Australian Army Ordnance Corps AASC Australian Army Service Corps AACS Australian Army Cooperation Squadron ACP Air Controller Party AIF Australian Imperial Force ALC Australian Landing Craft ALO Air Liaison Officer ALP Air Liaison Party ANGAU Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit AWM Australian War Memorial BM Brigade Major CMF Civil Military Force D Day FLEX Fleet Training Exercise FLP Fleet Training Publication FM Field Manual H Hour HMAS -

INSTRUMENT of SURRENDER We, Acting by Command of and in Behalf

INSTRUMENT OF SURRENDER We, acting by command of and in behalf of the Emperor of Japan, the Japanese Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters, hereby accept the provisions set forth in the declaration issued by the heads of the Governments of the United States, China, and Great Britain on 26 July 1945 at Potsdam, and subsequently adhered to by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which four powers are hereafter referred to as the Allied Powers. We hereby proclaim the unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers of the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters and of all Japanese armed forces and all armed forces under the Japanese control wherever situated. We hereby command all Japanese forces wherever situated and the Japanese people to cease hostilities forthwith, to preserve and save from damage all ships, aircraft, and military and civil property and to comply with all requirements which my be imposed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers or by agencies of the Japanese Government at his direction. We hereby command the Japanese Imperial Headquarters to issue at once orders to the Commanders of all Japanese forces and all forces under Japanese control wherever situated to surrender unconditionally themselves and all forces under their control. We hereby command all civil, military and naval officials to obey and enforce all proclamations, and orders and directives deemed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to be proper to effectuate this surrender and issued by him or under his authority and we direct all such officials to remain at their posts and to continue to perform their non-combatant duties unless specifically relieved by him or under his authority. -

The War in the Air 1914–1994

The War in the Air 1914–1994 American Edition Edited by Alan Stephens RAAF Aerospace Centre In cooperation with the RAAF Aerospace Centre Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama January 2001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The war in the air, 1914-1994 / edited by Alan Stephens ; in cooperation with the RAAF Air Power Studies Centre––American ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-087-6 1. Air power––History––Congresses. 2. Air warfare––History––Congresses. 3. Military history, Modern––20th century––Congresses. I. Stephens, Alan, 1944-II. RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. UG625.W367 2001 358.4′00904––dc21 00-068257 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Copyright © 1994 by the RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be made to the copyright holder. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHORS . vii PREFACE . xv ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS . xvii Essays Airpower in World War I, 1914–1918 . 1 Robin Higham The True Believers: Airpower between the Wars . 29 Alan Stephens Did the Bomber Always Get Through?: The Control of Strategic Airspace, 1939–1945 . 69 John McCarthy World War II: Air Support for Surface Forces . -

STRATEGY and COMMAND American Naval Strategist Alfred

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-51237-1 — Strategy and Command David Horner Frontmatter More Information S TRATEGY AND C OMMAND ISSUES IN AUSTRALIA’S TWENTIETH-CENTURY WARS American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote in 1908: ‘If the strategy be wrong, the skill of the general on the battlefield, the valour of the soldier, the brilliancy of the victory, however otherwise decisive, fail of their effect.’ In Strategy and Command, David Horner provides an important insight into the strategic decisions and military commanders who shaped Australia’s army history from the Boer War to the evolution of the command structure for the Australian Defence Force in the 2000s. He examines strategic decisions such as whether to go to war, the nature of the forces to be committed to the war, where the forces should be deployed and when to reduce the Australian commitment. The book also recounts decisions made by commanders at the highest level, which are passed on to those at the operational level, who are then required to produce their own plans to achieve the government’s aims through military operations at the tactical level. Strategy and Command is a compilation of half a century of research and writing on military history by one of Australia’s pre-eminent military historians. It is a crucial read for anyone interested in Australia’s involvement in twentieth-century wars. David Horner is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, where he was Professor of Australian Defence History for fifteen years. He has an international reputation for military history and strategic analysis and is considered Australia’s premier military historian.