The Gaon's Impact on the Interpretation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’S New Book Sin•A•Gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought

Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’s new book Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’s new book Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019) By Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz A Bashevkin-inspired Bio Blurb:[1] Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz is Rabbi of the Monmouth Torah Links community in Marlboro, NJ. His writings can be found in various rabbinic and popular journals, including Hakira, Ohr Yisroel, Nehoroy, Nitay Ne’emanim, and on Aish, Times of Israel, Torah Links, Seforim Blog, and elsewhere. His writings are rejected as often as they are accepted, and the four books he is currently working on will likely never see the light of day. “I’d rather laugh[2] with the sinners than cry with the saints; the sinners are much more fun.”[3] Fortunate is the man who follows not the advice of the wicked, nor stood in the path of the sinners, nor sat in the session of the scorners. (Psalms 1:1) One who hopes is always happy [and] without pain . hope keeps one alive . even one who has minimal good deeds . has hope . one who hopes, even if he enters Hell, he will be taken out . his hope is his purity, literally the Mikvah [4] of Yisroel . and this is the secret of repentance . (Ramchal, Derush ha-Kivuy) [5] Rabbi David Bashevkin is a man deeply steeped in sin. -

View Sample of This Item

Praise for Turning Judaism Outward “Wonderfully written as well as intensely thought provoking, Turning Judaism Outward is the most in-depth treatment of the life of the Rebbe ever written. !e author has managed to successfully reconstruct the history of one of the most important Jewish religious leaders of the 20th century, whose life has up to now been shrouded in mystery. A compassionate, engaging biography, this magni"cent work will open up many new avenues of research.” —Dana Evan Kaplan, author, Contemporary American Judaism: Transformation and Renewal; editor, !e Cambridge Companion to American Judaism “In contrast to other recent biographies of the Rebbe, Chaim Miller has availed himself of all the relevant textual sources and archival docu- ments to recount the details of one of the more fascinating religious leaders of the twentieth century. !rough the voice of the author, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of the Rebbe’s life is teeming with interest.... I am con"dent that readers of Miller’s book will derive great pleasure and receive much knowledge from this splendid and compel- ling portrait of the Rebbe.” —Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University “Only truly great biographers have been able to accomplish what Chaim Miller has with this book... I am awed by his work, and am now even more awed than ever before by the Rebbe’s personality and prodi- gious accomplishments.” —Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Executive Vice President Emeritus, Orthodox Union; Editor-in-Chief, Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud “A fascinating account of the life and legacy of a spiritual master. -

Urim Publications Jerusalem · New York

Urim Publications Jerusalem · New York Summer 2016 TOPICS Bible Commentary Biography Children Contemporary Issues Education Encyclopedia Fiction Hebrew Historical Fiction History Holidays Holocaust After the Holocaust Inspirational the Bells Still Ring Israel by Joseph Polak Jewish Law foreword by Elie Wiesel Jewish Thought Winner of the National Jewish Book Award 2015 in the category of Biography/Autobiography Lifecycle “This gem of a book, 70 years in the making, is already a classic, Passover Haggadah riveting in what it reveals, in the questions it releases.” –Merle Feld Prayer “As one of the last witnesses to the Shoah, certainly one of Psychology and Judaism the youngest, Joseph Polak has written a memoir that is an essential contribution to the body of Holocaust literature . Science and Judaism This is a must read for anyone not afraid of grappling with the unfathomable.” –Blu Greenberg Tikkun Olam “. Joseph’s voice originates from within Bergen-Belsen, and Women and Judaism perhaps poses the questions and challenges to G-d that Anne [Frank] might have posed, had she survived. His story and Title Index her story merge. These two youngsters from Holland, Anne forever a teenager, Joseph approaching the status of elder, provide a perspective of unusual insight from within the Holocaust, and from within survival.” –Robert Krell, MD Publishing since 1997 Urim Publications, 2015, Hardcover, 141 pages $19.95 (70 nis), isbn 978-965-524-162-4 2 www.UrimPublications.com American Interests in the Holy Land Revealed in Early Photographs From 1840 to 1940 by Lenny Ben-David Although Jewish life in the Holy Land reawakened during the 19th century, photographs of Jews in Palestine and the life they lived there are scarce. -

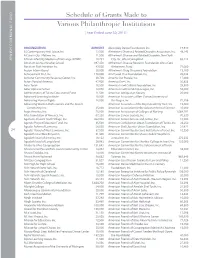

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

CONGREGATION TORAH OHR Education and Program Brochure

CONGREGATION TORAH OHR EducationEducation andand ProgramProgram BrochureBrochure 57795779 EDUCATION COMMITTEE 2018-2019 Benjamin S. Yasgur, Rabbi Dr. Chaim Shapiro, Rabbi Emeritus Josh Samborn, President Rabbi Kenneth Greene, Chairman Dr. Jack Prince, Chairman Emeritus David Cheslow Sam Colman Andrea Dolny Elly Edelman Barbara Gononsky Rabbi David Jacobowitz Judah Klein Rabbi Dr. Moshe Kranzler Marty Levine Dr. Sonny Meiselman Marcia Schrager Marvin Weinstein This brochure provides information about the many educational activities available to our Torah Ohr community throughout the year. Please read this brochure carefully and mark your calendar for special programs and the starting dates of classes you wish to attend. Further information will be available in the weekly bulletin when necessary. 19146 Lyons Road Boca Raton FL 33434 561-479-4049 TABLE OF CONTENTS SHABBAT MINYANIM & LEARNING 2 WEEKDAY MINYANIM & LEARNING 3 MINI-SERIES 4 CLASSES/SHIURIM 5-7 MEN & WOMEN EVENING KOLLEL 8 PROGRAMS 9 MEN’S CLUB BOOK REVIEWS 10 SISTERHOOD 11 LUNCH & LEARN 12 SHABBAT SHIRAH 13 ANNUAL SIYUM MISHNAYOT 13 SCHOLAR IN RESIDENCE 14 ANNUAL YOM IYUN 14 RABBI JACOB AND PEARL WEITMAN MEMORIAL LECTURE 15 YOM HAZIKARON, YOM HA’ATZMAUT, YOM YERUSHALAYIM 16 SPECIAL GROUPS 17 We would like to express our thanks to all those who have forwarded suggestions to the Education Committee relating to the spectrum of programs we offer. IN LOVING MEMORY Torah Ohr recognizes with sincere thanks the ongoing support of many of our programs by the following Memorial Funds. -

Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: the Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2017 Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh Henry Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. (2017). Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943 Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943 The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh הי׳׳ד Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira The Rebbe of Piaseczno, also known as the Aish Kodesh (Holy Fire) Son of Rabbi Elimelekh of Grodzisk Son-in-law of Rabbi Yerahmiel Moshe of Kozienice Henry Abramson 2017 CreateSpace Edition License Notes Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute portions of this book for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided appropriate citation of the source, in accordance with the Talmudic dictum of Rabbi Elazar in the name of Rabbi Hanina (Megilah 15a): “anyone who cites a teaching in the name of its author brings redemption to the world.” Copyright 2017 Henry Abramson Version 1.0 Heshvan 5778 (October 2017) Cover design by Meir Weiss and Tehilah Weiss Dedicated to the Piaseczno Rebbe and his students איך וויל זע גאר ניסט. -

IPG Spring 2019 Jewish Titles - March 2019 Page 1

Jewish Titles Spring 2019 {IPG} The Art of Inventing Hope Intimate Conversations with Elie Wiesel Howard Reich Summary The Art of Inventing Hope offers an unprecedented, in-depth conversation between the world’s most revered Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, and a son of survivors, Howard Reich. During the last four years of Wiesel’s life, he met frequently with Reich in New York, Chicago and Florida—and spoke often on the phone—to discuss the subject that linked them: both Wiesel and Reich’s father, Robert Reich, were liberated from Buchenwald death camp on April 11, 1945. What had started as an interview assignment from the Chicago Tribune quickly evolved into a friendship and a partnership. Reich and Wiesel believed their colloquy represented a unique exchange between two generations deeply affected by a cataclysmic event. Wiesel said to Reich, “I’ve never Chicago Review Press done anything like this before.” Here Wiesel—at the end of his life—looks back on his ideas and writings on 9781641601344 the Holocaust, synthesizing them in his conversations with Reich. The insights that Wiesel offered and Reich Pub Date: 5/7/19 On Sale Date: 5/7/19 illuminates can help the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors understand their painful $26.99/£23.99 UK inheritance, while inviting eve... Discount Code: LON Hardcover Contributor Bio 192 Pages Howard Reich has written for the Chicago Tribune since 1978 and joined the staff in 1983. He is the author Carton Qty: 0 of five books. Reich has won an Emmy Award and the Chicago Journalists Association named him Chicago History / Jewish HIS022000 Journalist of the Year in 2011. -

Urim Publications 2017 Catalog

Urim PublicationsJerusalem · New York celebrating 20 yearsof publishing Summer 2017 TOPICS Bible Commentary Biography Children Contemporary Issues Education Encyclopedia Fiction Hebrew Historical Fiction History Holidays Holocaust After the Holocaust Inspirational the Bells Still Ring Israel by Joseph Polak Jewish Law foreword by Elie Wiesel Jewish Thought Winner of the National Jewish Book Award 2015 in the category of Biography/Autobiography Lifecycle “This gem of a book, 70 years in the making, is already a classic, Passover Haggadah riveting in what it reveals, in the questions it releases.” –Merle Feld Prayer “As one of the last witnesses to the Shoah, certainly one of Psychology and Judaism the youngest, Joseph Polak has written a memoir that is an essential contribution to the body of Holocaust literature . Science and Judaism This is a must read for anyone not afraid of grappling with the unfathomable.” –Blu Greenberg Tikkun Olam “. Joseph’s voice originates from within Bergen-Belsen, and Women and Judaism perhaps poses the questions and challenges to G-d that Anne [Frank] might have posed, had she survived. His story and Title Index her story merge. These two youngsters from Holland, Anne forever a teenager, Joseph approaching the status of elder, provide a perspective of unusual insight from within the Holocaust, and from within survival.” –Robert Krell, MD Publishing since 1997 Urim Publications, 2015, Hardcover, 141 pages $19.95 (70 nis), isbn 978-965-524-162-4 2 www.UrimPublications.com American Interests World War I in the Holy Land in the Holy Land Revealed in Early Photographs Revealed in Early Photographs From 1840 to 1940 From 1914 to 1919 by Lenny Ben-David by Lenny Ben-David "I congratulate Lenny Ben-David on the publica- World War I in the Holy Land presents this his- tion of this major work illustrating over a century tory of the “great war” in short essays with more of American support for the Jews of the Holy Land. -

Proclamation Regarding Child Safety in the Orthodox Jewish Community

August 2016 – Av 5776 Proclamation Regarding Child Safety in the Orthodox Jewish Community In light of tragic suicides committed as a direct result of child sexual abuse, as well as other physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual consequences suffered by innocents in our Jewish Orthodox communities and beyond; and, Do not stand by while your fellow's")לא תעמוד על דם רעך ,In fulfillment of the Torah's precept blood is spilled"); and, As religious leaders responsible for our communities' institutions and their policies, as well as for the physical and spiritual welfare of the members of our communities We proclaim the following: ñ We acknowledge that sexual abuse of children - committed by family members, acquaintances, rabbis, teachers, counselors, youth leaders, and other professionals - exists in our communities. This abuse has caused and continues to cause immeasurable harm to the victims, their families, and our entire community; it can destroy lives. ñ We recognize in light of past experiences that our community could have responded in more responsible and sensitive ways to help victims and to hold perpetrators accountable. ñ We condemn attempts to ignore allegations of child sexual abuse. These efforts are harmful, contrary to Jewish law, and immoral. The reporting of reasonable suspicions of all forms of child abuse and neglect directly and promptly to the civil authorities is a requirement of Jewish law. There is no need for people acting responsibly to seek rabbinic approval prior to reporting. ñ We decry the use of Jewish law or the invocation of communal interests as a tool to silence victims or witnesses from reporting abuse. -

2020 JCF Giving Report

Jewish Communal Fund GIVING 2020 REPORT ABOUT JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND Jewish Communal Fund (JCF) is the largest and most active network of Jewish funders in the nation. JCF facilitates philanthropy for more than 8,000 people associated with 4,100 funds, totaling $2 billion in charitable assets. In FY 2020, our generous Fundholders granted out $536 million—27% of our assets—to charities in all sectors. The impact of JCF’s network of funders on the Jewish community and beyond is profound. In addition to an annual unrestricted grant to UJA-Federation of New York, JCF’s Special Gifts Fund (our endowment) has granted more than $20 million since 1999 to support programs in the Jewish community at home and abroad, including kosher food pantries and soup kitchens, day camp scholarships for children from low-income homes, and programs for Holocaust survivors with dementia. These charities are selected with the assistance of UJA-Federation of NY. For a simpler, easier, smarter way to give, look no further than the Jewish Communal Fund. To learn more about JCF, visit jcfny.org or call us at (212) 752-8277. INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Letter from the President and CEO 2 Introduction 3–6 The JCF Philanthropic Community 7–15 Grants 16 Contributions 17–28 Grants Listing 2 www.jcfny.org • 212-752-8277 Letter from the President and CEO JCF’s extraordinarily generous Fundholders increased their giving to meet the tremendous needs that arose amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In FY 2020, JCF Fundholders recommended more than 64,000 grants totaling a record-breaking $536 million to charities in every sector. -

Hamodia Bio.Pdf

C8 HAMODIA 11 TAMMUZ 5773 JUNE 19, 2013 Community Biography / By Yochonon Donn Hagaon Harav Dovid Lifshitz, zt”l: A Rosh Yeshivah Who Cared for Every Yid In honor of the Suvalker Rav’s 20th Yahrtzeit “Are you sure you could on Erev Pesach,” said Mrs. accurately portray Rav Stein. “Some nights he would Lifshitz?” stay up through the night” to Rabbi Binyamin Yudin, a read of the pain people talmid of Harav Dovid Lifshitz, expressed in their letters. the famed Suvalker Rav who was a Rosh Yeshivah in ‘We Are All Suvalkers’ Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok But aside from Reb Dovid Elchanan for nearly a half cen- being a lamdan, an askan and a tury, was doubtful that such a Rosh Yeshivah, he was a Rav great mind, yet a man not as and posek in Suvalk. The repu- well-known as other Gedolim, tation that preceded him led would be accurately portrayed the Skokie, Illinois, kehillah in a newspaper article. where he was initially hired as But for the 20th yahrtzeit Rosh Yeshivah of Beis Medrash commemoration Monday, L’Torah after coming to the Rabbi Yudin agreed that the U.S., to declare: “We are all attempt must be made. Suvalkers.” Rabbi Yudin was described It was in Suvalk, a city in by the family of Harav Lifshitz, northeastern Poland close to whose yahrtzeit was marked the border with Lithuania, that this week with shiurim and Reb Dovid first became known events across the tri-state area, to the world. as someone firmly in the family Born in 1906 to Reb Yaakov loop during the 1960s, when he Arye and Ittel Lifshitz, Reb was in the Suvalker Rav’s shiur. -

The 5 Towns Jewish Times! You Can Upload Your Digital Photos and See Them Printed in the Weekly Edition of the 5 Towns Jewish Times

See Ad, Page 20 $1.00 WWW.5TJT.COM !vfubj igfhkhhrp t VOL. 8 NO. 12 27 KISLEV 5768 .en ,arp DECEMBER 7, 2007 INSIDE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK LIGHTING UP THE CHANUKAH NIGHT Friday-Night Prayers BY LARRY GORDON Hannah Reich Berman 28 MindBiz The PR War On Terror Esther Mann, LMSW 30 The surge is working, but we ments, then we are just losing Laws of Chanukah may be losing the war miser- the war. Rabbi Yair Hoffman 39 ably anyway. That’s the public- This war is being fought relations war on terror that I’m not on the battlefield, but Daf Yomi Insights referring to, and there is no rather in the international Rabbi Avrohom Sebrow 56 military surge needed in order media—on CNN, FOX News, to set this all-important aspect the New York Times, the Photo Lost With A Map of the war on the right course. Washington Post, and so on. Michelle Nevada 74 Thomas Cr By Ira As long as international terror Mostly, however, it is being merchants and criminals like fought in the electronic media Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and that is highly competitive and eations Osama bin Laden can grab the has a need for breaking, dis- world’s attention with outra- Rav Moshe Weinberger, shlita, of Aish Kodesh in Woodmere lighting the geous and inflammatory state- Continued on Page 6 Chabad menorah in Cedarhurst Park. More Photos, Page 67 HEARD IN THE BAGEL STORE A FALAFEL STORY Enough Warm Weather B Y LA URA BEN-DAVID around the place and deter- BY LARRY GORDON Bar Mitzvah of Ian Mark.