Acting Comptroller Julie L. Williams Testimony Before the U.S. Senate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 83 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1997 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Richard Spillenkothen • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 947 TREASURY AND FEDERAL RESERVE OPEN formance can improve investor and counterparty MARKET OPERATIONS decisions, thus improving market discipline on banking organizations and other companies, During the third quarter of 1997, the dollar before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, appreciated 5.0 percent against the Japanese yen Securities and Government Sponsored Enter- and 0.8 percent against the German mark. On a prises of the House Committee on Banking and trade-weighted basis against other Group of Ten Financial Services, October 1, 1997. currencies, the dollar appreciated 1.4 percent. The U.S. monetary authorities did not undertake 96\ Theodore E. Allison, Assistant to the Board of any intervention in the foreign exchange mar- Governors for Federal Reserve System Affairs, kets during the quarter. reports on the Federal Reserve's plans for deal- ing with some new-design $50 notes that 953 STAFF STUDY SUMMARY were imperfectly printed, including the Federal Reserve's view of the quality and quantity of In The Cost of Implementing Consumer Finan- $50 notes currently being produced by the cial Regulations, the authors present results for Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the options U.S. -

By:Bill Medley

By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System Published by the Public Affairs Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 1 Memorial Drive • Kansas City, MO 64198 Diane M. Raley, publisher Lowell C. Jones, executive editor Bill Medley, author Casey McKinley, designer Cindy Edwards, archivist All rights reserved, Copyright © 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publisher. First Edition, July 2014 The Highways of Commerce • III �ontents Foreword VII Chapter One A Calculus of Chaos: Commerce in Early America 1 Chapter Two “Order out of Confusion:” The Suffolk Bank 7 Chapter Three “A New Era:” The Clearinghouse 19 Chapter Four “A Famine of Currency:” The Panic of 1907 27 Chapter Five “The Highways of Commerce:” The Road to a Central Bank 35 Chapter Six “A problem…of great novelty:” Building a New Clearing System 45 Chapter Seven Bank Robbers and Bolsheviks: The Par Clearance Controversy 55 Chapter Eight “A Plump Automatic Bookkeeper:” The Rise of Banking Automation 71 Chapter Nine Control and Competition: The Monetary Control Act 83 Chapter Ten The Fed’s Air Force: A Plan for the Future 95 Chapter Eleven Disruption and Evolution: The Development of Check 21 105 Chapter Twelve Banks vs. Merchants: The Durbin Amendment 113 Afterword The Path Ahead 125 Endnotes 128 Sources and Selected Bibliography 146 Photo Credits 154 Index 160 Contents • V ForewordAs Congress undertook the task of designing a central bank for the United States in 1913, it was clear that lawmakers intended for the new institution to play a key role in improving the performance of the nation’s payments system. -

The Business of Banking: Before and After Gramm-Leach-Bliley

The Business of Banking: Before and After Gramm-Leach-Bliley Jonathan R. Macey* I. INTRO DUCTION ......................................................................................................... 691 II. BUSINESS OF BANKING: THE ONCE AND FUTURE BANKING INDUSTRY .................... 695 A. The Current Theory of Banking ......................................................................... 695 B. A Modification of the Current Theory: Banks as Insurers................................. 697 1. Bank CapitalStructure ................................................................................. 699 2. D eposit Insurance......................................................................................... 699 3. Banks, Narrow Banks, and Mutual Funds .................................................... 701 a. Money Market Mutual Funds Versus Bank Checking Accounts .............. 701 b. Why Banks Make Loans with Depositors' Funds .................................... 703 c. Banks' Unique Role in the Economy ....................................................... 707 III. GRAMM-LEACH-BLILEY ACT: BANKS VERSUS FINANCIAL HOLDING C O M PA N IES .............................................................................................................. 709 A . F unctional R egulation........................................................................................ 710 B . P rivacy ............................................................................................................... 7 13 C. The Demandfor FinancialServices -

The Creature from Jekyll Island

ABOUT THE COVER The use of the Great Seal of the United States is not without significance. At first we contemplated having an artist change the eagle into a vulture. That, we thought, would attract attention and also make a statement. Upon reflection, however, we realized that the vulture is really harmless. It may be ugly, but it is a scavenger, not a killer. The eagle, on the other hand, is a predator. It is a regal creature to behold, but it is deadly to its prey. Furthermore, as portrayed on the dollar, it is protected by the shield of the United States government even though it is independent of it. Finally, it holds within its grasp the choice between peace or war. The parallels were too great to ignore. We decided to keep the eagle. G. Edward Griffin is a writer and documentary film producer with many successful titles to his credit. Listed in Who's Who in America, he is well known because of his talent for researching difficult topics and presenting them in clear terms that all can (Continued on inside of back cover) ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS BOOK Single price $19.50* HOW TO READ 40% discount on case purchases, 12 books per case. (That's $11.70 per book, $140.40 per case)* THIS BOOK California residents add 7 Vi % sales tax. Thick books can be intimidating. tend to put For shipping, handling, and insurance, add: We off reading them until we have a suitably large $5.50 for the first copy plus $1.20 for each additional copy block of time—which is to say, often they are ($18.70 per case) never read. -

Download (Pdf)

VOLUME 66 • NUMBER 10 • OCTOBER 1980 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Washington, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • Stephen H. Axilrod • John M. Denkler Janet O. Hart • James L. Kichline • Neal L. Petersen • Edwin M. Truman Naomi P. Salus, Coordinator • Sandra Pianalto, Staff Assistant The FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. The artwork is provided by the Graphic Communications Section under the direction of Peter G. Thomas. Editorial support is furnished by the Economic Editing Unit headed by Mendelle T. Berenson. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Table of Contents 817 THE IMPACT OF ing of negotiable order of withdrawal ac- RISING OIL PRICES ON THE MAJOR counts. FOREIGN INDUSTRIAL COUNTRIES Report on assets and liabilities of foreign The recent surge in the world price of oil branches of member banks, year-end has led to a strong swing toward deficit in 1979. the current-account balances, a slowing of Availability of description of the opera- economic activity, and an acceleration of tion of the discount window. inflation in the major foreign industrial countries. Correction of data on foreign currencies. Changes in Board staff. 825 INDUSTRIAL PROD UCTION Meeting of Consumer Advisory Council. Output increased about 1.0 percent in September. Revision of list of over-the-counter stocks that are subject to margin regulations. 827 STATEMENT TO CONGRESS Admission of three state banks to mem- bership in the Federal Reserve System. -

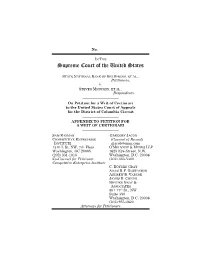

APPENDIX to PETITION for a WRIT of CERTIORARI ______SAM KAZMAN GREGORY JACOB COMPETITIVE ENTERPRISE (Counsel of Record) INSTITUTE [email protected] 1310 L St

No. ______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ____________________ STATE NATIONAL BANK OF BIG SPRING, ET AL., Petitioners, v. STEVEN MNUCHIN, ET AL., Respondents. ____________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ____________________ APPENDIX TO PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ____________________ SAM KAZMAN GREGORY JACOB COMPETITIVE ENTERPRISE (Counsel of Record) INSTITUTE [email protected] 1310 L St. NW, 7th Floor O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP Washington, DC 20005 1625 Eye Street, N.W. (202) 331-1010 Washington, D.C. 20006 Co-Counsel for Petitioner (202) 383-5300 Competitive Enterprise Institute C. BOYDEN GRAY ADAM R.F. GUSTAFSON ANDREW R. VARCOE JAMES R. CONDE BOYDEN GRAY & ASSOCIATES 801 17th St., NW Suite 350 Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 955-0620 Attorneys for Petitioners APPENDIX Court of Appeals Summary Affirmance (D.C. Cir. June 8, 2018) ................................ 1a District Court Judgment (D.D.C. Feb. 16, 2018) .................................. 3a District Court Summary Judgment Order (D.D.C. July 12, 2016) .................................. 5a U.S. Const. Art. I, Sec. 9, Cl. 7 (Appropriations Clause) ............................. 24a U.S. Const. Art. II, Sec. 2, Cl. 2 (Appointments Clause) ............................... 25a Excerpts of Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Title X, §§ 1001-1037 ................................................ 26a Second Amended Complaint (D.D.C. Feb. 13, 2013) ...............................161a Opinion in PHH Corp. v. CFPB, No. 15-1177 (D.C. Cir. Jan. 31, 2018) ............................244a 1a APPENDIX A - COURT OF APPEALS’ SUMMARY AFFIRMANCE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT No. 18-5062 September Term, 2017 1:12-cv-01032-ESH Filed On: August 3, 2018 State National Bank of Big Spring, et al., Appellants State of South Carolina, et al., Appellees v. -

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, March/April 2010

Federal RReserveE BankV of St. LIouiEs W MARCH /APRIL 2010 VOLUME 92, N UMBER 2 R E V I E W Lessons Learned? Comparing the Federal Reserve’s Responses to the Crises of 1929-1933 and 2007-2009 David C. Wheelock Institutions and Government Growth: A Comparison of the 1890s and the 1930s Thomas A. Garrett, Andrew F. Kozak, and Russell M. Rhine M A R Fiscal Multipliers in War and in Peace C H / David Andolfatto A P R I L 2 0 1 FOMC Learning and Productivity Growth (1985-2003): 0 • A Reading of the Record V O Richard G. Anderson and Kevin L. Kliesen L U M E 9 2 N U M B E R 2 89 REVIEW Lessons Learned? Comparing the Federal Reserve’s Responses to the Director of Research Christopher J. Waller Crises of 1929-1933 and 2007-2009 Senior Policy Adviser David C. Wheelock Robert H. Rasche Deputy Director of Research Cletus C. Coughlin 109 Review Editor-in-Chief Institutions and Government Growth: William T. Gavin A Comparison of the 1890s and the 1930s Research Economists Thomas A. Garrett, Andrew F. Kozak, and Richard G. Anderson Russell M. Rhine David Andolfatto Alejandro Badel Subhayu Bandyopadhyay Silvio Contessi 121 Riccardo DiCecio Thomas A. Garrett Fiscal Multipliers in War and in Peace Carlos Garriga David Andolfatto Massimo Guidolin Rubén Hernández-Murillo Luciana Juvenal Natalia A. Kolesnikova 129 Michael W. McCracken FOMC Learning and Productivity Growth Christopher J. Neely Michael T. Owyang (1985-2003): A Reading of the Record Adrian Peralta-Alva Richard G. Anderson and Kevin L. -

Currency Wars and the Erosion of Dollar Hegemony

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 38 Issue 1 2016 Currency Wars and the Erosion of Dollar Hegemony Lan Cao Fowler School of Law, Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the International Trade Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Lan Cao, Currency Wars and the Erosion of Dollar Hegemony, 38 MICH. J. INT'L L. 57 (2016). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol38/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURRENCY WARS AND THE EROSION OF DOLLAR HEGEMONY Lan Cao* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 57 I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF MONEY .......................... 73 A. Commodities, Coins, and Paper Money .............. 73 B. Central Bank, Federal Reserve and the Rise of the Dollar .............................................. 76 C. The Dollar in the Depression........................ 78 II. THE BRETTON WOODS AGREEMENT AND THE RISE OF THE DOLLAR ........................................... 81 III. CURRENT CURRENCY WARS ............................ 89 A. Dollar-Yuan Rivalry ................................ 90 B. New Non-Dollar Based Systems ..................... 99 CONCLUSION ................................................... 112 INTRODUCTION In recent years, much attention has been paid to the wars in Iraq, Af- ghanistan, and Syria, and the nuclear ambitions of Iran. Wars and breaches of the peace are of paramount importance and thus are rightly matters of international and national concern. -

Statistical Supplement Printable Version

March 2006 Statistical Supplement to the Federal Reserve BULLETIN The Statistical Supplement to the Federal Reserve Bulletin (ISSN 1547-6863) is published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC 20551, and may be obtained from Publications Fulfillment, Mail Stop 127, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC 20551. Calls pertaining to subscriptions should be directed to Publications Fulfillment (202) 452-3245. The regular subscription price in the United States and its commonwealths and territories, and in Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Republic of Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, and Venezuela is $25.00 per year or $2.50 per copy; elsewhere, $35.00 per year or $3.50 per copy. Remittance should be made payable to the order of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in a form collectible at par in U.S. currency. A subscription to the Statistical Supplement to the Federal Reserve Bulletin may also be obtained by using the publications order form available on the Board’s web site, at www.federalreserve.gov. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Statistical Supplement to the Federal Reserve Bulletin, PUBLICA- TIONS FULFILLMENT, Mail Stop 127, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC 20551. Volume 3 Number 3 March 2006 Statistical Supplement to the Federal Reserve BULLETIN Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, D.C. ii Publications Committee Rosanna Pianalto Cameron, Chair Scott G. Alvarez Sandra Braunstein Marianne M. Emerson Jennifer J. Johnson Karen H. -

SAM AHN (3Rd at This File Number)

Subject: File No. SR-CboeBZX-2018-040 From: SAM AHN (3rd at this file number) This is my sixth comment on bitcoin. The first one was put at SR-CboeBZX-2018-040 (right here) on 08/13/2018, the second at SR-NYSEArca-2017-139 on 08/16/2018, the third at SR-CboeBZX-2018-001 on 08/17/2018, the fourth at SR-NYSEArca-2018-02 on 08/21/2018, and the fifth right here again on 08/28/2018. All my writings including this revolve around intrinsic value. Satoshi Nakamoto intended to create a new currency and a new payment system, but the new currency bitcoins are being traded like securities and the payment system Bitcoin Network has degenerated into a decentralized Ponzi scheme. While explaining it, this writing happened to be a long one. In fear of not being read at all, I enumerate some of what the readers can find herein, as below: 1. It is not stated in the bitcoin whitepaper that a new currency would be created. 2. A new currency was defined differently than it was illustrated, in the whitepaper. 3. Cryptocurrency was defined a chain of signatures, meaning blockchain, in the whitepaper. 4. Mining means attempting to get 64-digit codes beginning with 16 to 18 zeroes. 5. One success of mining was entitled to about 50 bitcoins for 4 years from 2009. 6. One success of mining will be entitled to about 6.25 bitcoins for 4 years from 2021. 7. The definition in 3 above is contradictory to the facts in 4 through 6 above. -

Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act

PUBLIC LAW 106±102ÐNOV. 12, 1999 GRAMM±LEACH±BLILEY ACT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:09 Aug 30, 2000 Jkt 079139 PO 00102 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL102.106 apps13 PsN: PUBL102 113 STAT. 1338 PUBLIC LAW 106±102ÐNOV. 12, 1999 Public Law 106±102 106th Congress An Act To enhance competition in the financial services industry by providing a prudential Nov. 12, 1999 framework for the affiliation of banks, securities firms, insurance companies, [S. 900] and other financial service providers, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Gramm-Leach- the United States of America in Congress assembled, Bliley Act. Inter- SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. governmental relations. (a) SHORT TITLE.ÐThis Act may be cited as the ``Gramm-Leach- 12 USC 1811 Bliley Act''. note. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.ÐThe table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. TITLE IÐFACILITATING AFFILIATION AMONG BANKS, SECURITIES FIRMS, AND INSURANCE COMPANIES Subtitle AÐAffiliations Sec. 101. Glass-Steagall Act repeals. Sec. 102. Activity restrictions applicable to bank holding companies that are not fi- nancial holding companies. Sec. 103. Financial activities. Sec. 104. Operation of State law. Sec. 105. Mutual bank holding companies authorized. Sec. 106. Prohibition on deposit production offices. Sec. 107. Cross marketing restriction; limited purpose bank relief; divestiture. Sec. 108. Use of subordinated debt to protect financial system and deposit funds from ``too big to fail'' institutions. Sec. 109. Study of financial modernization's effect on the accessibility of small busi- ness and farm loans. -

A Joint Commissioners' Study on Financial Services Modernization

FINANCIAL SERVICES MODERNIZATION FOR TEXAS Impact of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 O August 15, 2000 A Joint Study Conducted by: Texas Department of Banking Texas Department of Insurance Texas Savings and Loan Department Texas State Securities Board Acknowledgements This study was conducted under the direction of the Commissioners of the four agencies and their allocation of resources to complete this task is greatly appreciated. Task Force Members provided invaluable contributions of time, research, and personal commitment to complete this endeavor. Sincere appreciation is extended to all the participants of this study. Commissioners Randall S. James Texas Department of Banking Jose Montemayor Texas Department of Insurance James L. Pledger Texas Savings and Loan Denise Voigt Crawford Texas State Securities Board Task Force Participants Robert Bacon Department of Banking Kevin Brady Department of Insurance Lynda Drake Department of Banking Ryan Eckstein Department of Banking Gayle Griffin Department of Banking Don Hanson Department of Insurance Jack Hohengarten Attorney General’s Office Tim Irvine Savings and Loan Department Everette Jobe Department of Banking Steve Martin Department of Banking David Mattax Attorney General’s Office John Morgan State Securities Board Tom Spradin State Securities Board David Weaver State Securities Board FINANCIAL SERVICES MODERNIZATION FOR TEXAS Impact of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 August 15, 2000 Glossary of Acronyms and Other Shortened References in this Report .........................................ii