INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Ii Foreign Policy Foundation of Saudi Arabia and Saudi Arabia Relations with Several International Organizations

CHAPTER II FOREIGN POLICY FOUNDATION OF SAUDI ARABIA AND SAUDI ARABIA RELATIONS WITH SEVERAL INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS This chapter discusses the foreign policy foundation of Saudi Arabia including the general introduction about the State of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Arabia political system, the ruling family, Saudi’s Arabia foreign policy. This chapter also discusses the Saudi Arabia relations with several international organizations. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a country that has many roles, well in the country of the Arabian Peninsula as well as the global environment. The country that still adhere this royal system reserves and abundant oil production as the supporter, the economy of their country then make the country to be respected by the entire of international community. Regardless of the reason, Saudi Arabia also became the Qibla for Muslims around the world because there are two of the holiest city which is Mecca and Medina, at once the birth of Muslim civilization in the era of Prophet Muhammad SAW. A. Geography of Saudi Arabia The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a country located in Southwest Asia, the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula, bordering with the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, as well as Northern Yemen. The extensive coastlines in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea provide a great influence on shipping (especially crude oil) through the Persian Gulf and the Suez Canal. The Kingdom occupies 80 percent of the Arabian Peninsula. Estimates of the Saudi government are at 2,217,949 15 square kilometres, while other leading estimates vary between 2,149,690 and 2,240,000 kilometres. -

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

The Birth of Al-Wahabi Movement and Its Historical Roots

The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Original Document Information ~o·c·u·m·e·n~tI!i#~:I~S=!!G~Q~-2!110~0~3~-0~0~0~4'!i66~5~9~"""5!Ii!IlI on: nglis Title: Correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General Military Intelligence irectorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of AI-Wahhabiyyah ovement and its Historical Roots" age: ARABIC otal Pages: 53 nclusive Pages: 52 versized Pages: PAPER ORIGINAL IRAQI FREEDOM e: ountry Of Origin: IRAQ ors Classification: SECRET Translation Information Translation # Classification Status Translating Agency ARTIAL SGQ-2003-00046659-HT DIA OMPLETED GQ-2003-00046659-HT FULL COMPLETED VTC TC Linked Documents I Document 2003-00046659 ISGQ-~2~00~3~-0~0~04~6~6~5~9-'7':H=T~(M~UI:7::ti""=-p:-a"""::rt~)-----------~II • cmpc-m/ISGQ-2003-00046659-HT.pdf • cmpc-mIlSGQ-2003-00046659.pdf GQ-2003-00046659-HT-NVTC ·on Status: NOT AVAILABLE lation Status: NOT AVAILABLE Related Document Numbers Document Number Type Document Number y Number -2003-00046659 161 The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Keyword Categories Biographic Information arne: AL- 'AMIRI, SA'IO MAHMUO NAJM Other Attribute: MILITARY RANK: Colonel Other Attribute: ORGANIZATION: General Military Intelligence Directorate Photograph Available Sex: Male Document Remarks These 53 pages contain correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General i1itary Intelligence Directorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of I-Wahhabiyyah Movement and its Historical Roots". -

Newsroom Convergence in Saudi Press Organisations a Qualitative Study Into Four Newsrooms of Traditional Newspapers 1

Newsroom Convergence in Saudi Press organisations A qualitative study into four newsrooms of traditional newspapers 1 Ahmed A. Alzahrani2 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Journalism Studies University of Sheffield September 2016 1 To cite this thesis: Alzahrani, A. (2016) Newsroom Convergence in Saudi Press Organisations: A qualitative study into four newsrooms of traditional newspapers. PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield. 2 [email protected] Alzahrani Newsroom Convergence in Saudi Press organisations Abstract This is the first study of its kind about newsroom convergence and multi- skilled journalists in Saudi newspaper organisations and aimed to fill a gap in the literature about this particular issue in the Saudi context. The study investigated transformations, implications and consequences of technological convergence at four Saudi traditional newspaper organisations; Al-Madina, Alriyadh, Alyaum, and Alwatan. This thesis has explored the particular impacts of online journalistic production in traditional newspaper organisations to identify changes and perhaps challenges occurring in newspaper newsrooms. The study used the observation method in the four newsrooms and in-depth interviews with open ended questions with 60 professionals. The findings confirmed that there are ongoing transformations in the newsrooms. Yet, these transformations are challenged by regulatory, business, and cultural forces. Alyaum was the only newsroom to introduce new integrated newsroom. Journalists are observing and using new communication technologies in the workplace. However, there are difficulties in this process such as tensions in the newsrooms and shortage of qualified and trained journalists in the Saudi media market especially, multiskilled journalists. Despite embracing online and digital technology in news production and disruption, the four Saudi newspapers are still prioritising the traditional print side as it is generating more than 95 % of the annual revenue. -

Aza E Zainab

Aza E Zainab Compiled by Sakina Hasan Askari nd 2 Edition 1429/2008 1 Contents Introduction 3 Karbala to Koofa 8 Bazaare Koofa 17 Darbar e Ibn Ziyad 29 Kufa to Sham 41 News Reaching Medina 51 Qasr e Shireen 62 Bazaare Sham 75 Darbar e Yazeed 87 Zindan e Sham 101 Shahadat Bibi Sakina 111 Rihayi 126 Daqila Karbala 135 Arbayeen 147 Reaching Medina 164 At Rauza e Rasool 175 Umm e Rabaab‟s Grief 185 Bibi Kulsoom 195 Bibi zainab 209 RuqsatAyyam e Aza 226 Ziarat 240 Route Karbala to Sham 242 Index of First Lines 248 Bibliography 251 2 Introduction Imam Hussain AS, an ideal for all who believe in righteous causes, a gem of the purest rays, a shining light, was martyred in Karbala on the tenth day of Moharram in 61 A.H. The earliest examples of lamentations for the Imam have been from the family of the Holy Prophet SAW. These elegies are traced back to the ladies of the Prophet‟s household. Poems composed were recited in majalis, the gatherings to remember the events of Karbala. The Holy Prophet SAW, himself, is recorded as foretelling the martyrdom of his grandson Hussain AS at the time of his birth. In that first majlis, Imam Ali AS and Bibi Fatima AS, the parents of Imam Hussain AS , heard from the Holy Prophet about the martyrdom and wept. Imam Hasan AS, his brother, as he suffered from the effects of poison administered to him, spoke of the greater pain and agony that Imam Hussain would suffer in Karbala. -

Saudi Arabia.Pdf

A saudi man with his horse Performance of Al Ardha, the Saudi national dance in Riyadh Flickr / Charles Roffey Flickr / Abraham Puthoor SAUDI ARABIA Dec. 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 | Geography . 6 Introduction . 6 Geographical Divisions . 7 Asir, the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Rub al-Khali and the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Hejaz, the Western Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Nejd, the Central Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 The Eastern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Topographical Divisions . .. 9 Deserts and Mountains � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Climate . .. 10 Bodies of Water . 11 Red Sea � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Persian Gulf � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Wadis � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Major Cities . 12 Riyadh � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �12 Jeddah � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Mecca � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Successful Strategies for Media Houses

In cooperation with 9th WAN-IFRA Middle East Conference · 12-13 March 2014, Dubai THE FUTURE STARTS TODAY SUCCESSFUL STRATEGIES FOR MEDIA HOUSES GOLD PARTNERS SILVER PARTNERS SUPPORTING PARTNERS In cooperation with 9th WAN-IFRA Middle East Conference · 12-13 March 2014, Dubai Programme Day 1 – March 12th 14:30 Driving Newsroom Innovation with the Power of Your People “How to unleash newsroom innovation by tapping into the Offical opening talent of your staff”. Journalists at news desks and on the road are the people 10:00 Official opening of the conference that transform newsroom strategies into reality. They Welcome speech: breathe life into the vision, taking goals, milestones and H.R.H. Princess Rym Ali, Jordan metrics from flipcharts and excel spreadsheets into the real world. Without well-trained staff and an environment that 10:30 Welcome address from the region nurtures rather than stifles creativity, a newsroom transfor- Dhaen Shaeen, CEO of Publishing Sector, mation may never reach its full potential. Dubai Media Incorporated, Dubai, UAE Jonathan Halls, Adjunct Prof, George Washington University, USA Saleh Alhumaidan, Managing Director, Al-Yaum Media House Dammam, Saudi Arabia, and Chairman of 15:00 Focusing on the Local: Mantiqti, the the WAN-IFRA Middle East Committee region’s first quality hyperlocal newspaper Mohammad Abdullah, Managing Director, Media Mantiqti, the first “hyper local” free newspaper in Egypt Cluster – TECOM Investments, Dubai, UAE and the Middle East is distributed across Cairo’s vibrant downtown district – door to door to residents, at branded 10:50 Welcome address from WAN-IFRA stands in cafes and among local businesses ranging from Vincent Peyrègne, Chief Executive Officer, the Stock Exchange to medical doctors, lawyers, tourism WAN-IFRA, France companies and others. -

MONTHLY BULLETIN VOLUME 55; ISSUE :55 SEPTEMBER—OCTOBER 2013 News Updates MIDDLE EAST PUBLISHERS’ ASSOCIATION

MONTHLY BULLETIN VOLUME 55; ISSUE :55 SEPTEMBER—OCTOBER 2013 News Updates MIDDLE EAST PUBLISHERS’ ASSOCIATION MEPA'S OBJECTIVES: Sayidaty.net No. 1 Arab women's website worldwide ! • To encourage the widest possible spread Sayidaty, a sister publication of Arab News, reached of publications throughout Middle East in August first place among the most visited Arab magazine and beyond. websites for women worldwide, according to Effec- • To promote and protect by all lawful means the publishing industry in Middle tive Measure, a leading online measurement provider in the East world. • To protect members by dealing collec- More than 1.6 million unique users visited Sayidaty last tively with problems. month, generating more than 20 million page views from • To cooperate for mutual benefits with around the world with half of the visitors coming from the other organizations concerned in the Prince Turki bin Salman creation, production and distribution of GCC, according to Google Analytics. publications. Sayidaty launched its new website in September 2012 with a strategy of covering all • To promote the development of public that are required by Arab women in their daily lives. The content includes social issues, interest in publications in association fashions, jewelry, children’s education, marriage, family relations, cuisine, health, with other publishing organizations with work, lifestyle, home, décor capacity building and more. similar objectives. • To serve as a medium for exchange of Sayidaty is considered the largest circulating women’s magazine in the Middle East. ideas with respect to publication, sales The success of its website on the Internet reflects its wealthy content in both print and copyright and other matters of interest. -

Arab Filmmakers of the Middle East

Armes roy Armes is Professor Emeritus of Film “Constitutes a ‘counter-reading’ of Film and MEdia • MIddle EasT at Middlesex University. He has published received views and assumptions widely on world cinema. He is author of Arab Filmmakers Arab Filmmakers Dictionary of African Filmmakers (IUP, 2008). The fragmented history of Arab about the absence of Arab cinema Arab Filmmakers in the Middle East.” —michael T. martin, Middle Eastern cinema—with its Black Film Center/Archive, of the Indiana University powerful documentary component— reflects all too clearly the fragmented Middle East history of the Arab peoples and is in- “Esential for libraries and useful for individual readers who will deed comprehensible only when this find essays on subjects rarely treat- history is taken into account. While ed in English.” —Kevin Dwyer, neighboring countries, such as Tur- A D i c t i o n A r y American University in Cairo key, Israel, and Iran, have coherent the of national film histories which have In this landmark dictionary, Roy Armes details the scope and diversity of filmmak- been comprehensively documented, ing across the Arab Middle East. Listing Middle East Middle more than 550 feature films by more than the Arab Middle East has been given 250 filmmakers, and short and documentary comparatively little attention. films by another 900 filmmakers, this vol- ume covers the film production in Iraq, Jor- —from the introduction dan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and the Gulf States. An introduction by Armes locates film and filmmaking traditions in the region from early efforts in the silent era to state- funded productions by isolated filmmakers and politically engaged documentarians. -

A Case Study of Memri's

AL GHANNAM, ABDULAZIZ G., Ph.D., December 2019 TRANSLATION STUDIES IDEOLOGY IN MEDIA TRANSLATION: A CASE STUDY OF MEMRI’S TRANSLATIONS (294 PP.) Dissertation Advisor: Brian James Baer Translation is an invaluable tool for communicating between cultures and for bridging the “knowledge gap.” Based on this fact, the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) claims that the purpose of its translations of media content from the Middle East, mainly the Arabic-speaking world, is to bridge the knowledge gap that exists between the West and Middle Eastern countries. Although MEMRI’s stated goal is a generous and worthy one, its translations have attracted criticism from major translation scholars such as Mona Baker (2005, 2006, 2010a) and journalists such as Brian Whitaker (2002, 2007), as well as scholars from history and political studies. The main criticism regarding MEMRI’s translations revolves around the question of selectivity, or which texts are chosen for translation. However, no study to date has provided comprehensive evidence to support or refute that charge, which this study aims to do. This study focuses on English translations of texts and video clips that were found in the Saudi Arabia translation archive, published and available online on MEMRI’s website. By investigating all the Saudi media sources (e.g., newspapers, TV channels, Twitter, YouTube, etc.) from which MEMRI makes its selection of texts for translation, this study provides statistical evidence as to whether MEMRI’s translations are representative of what is being circulated in the source culture (Saudi Arabia) media. Supporting evidence is sought in MEMRI’s approach to the translation of titles and in its translation of video clips (subtitling). -

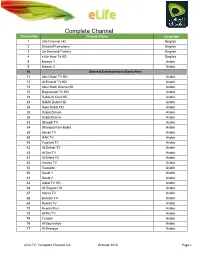

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad