Resident Canada Goose Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niche Overlap Among Anglers, Fishers and Cormorants and Their Removals

Fisheries Research 238 (2021) 105894 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/®shres Niche overlap among anglers, fishersand cormorants and their removals of fish biomass: A case from brackish lagoon ecosystems in the southern Baltic Sea Robert Arlinghaus a,b,*, Jorrit Lucas b, Marc Simon Weltersbach c, Dieter Komle¨ a, Helmut M. Winkler d, Carsten Riepe a,c, Carsten Kühn e, Harry V. Strehlow c a Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587, Berlin, Germany b Division of Integrative Fisheries Management, Faculty of Life Sciences, Humboldt-Universitat¨ zu Berlin, Invalidenstrasse 42, 10115, Berlin, Germany c Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries, Alter Hafen Süd 2, 18069, Rostock, Germany d General and Specific Zoology, Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany e Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries, Institute of Fisheries, Fischerweg 408, 18069, Rostock, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Handled by Steven X. Cadrin We used time series, diet studies and angler surveys to examine the potential for conflict in brackish lagoon fisheries of the southern Baltic Sea in Germany, specifically focusing on interactions among commercial and Keywords: recreational fisheries as well as fisheries and cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis). For the time period Fish-eating wildlife between 2011 and 2015, commercial fisheries were responsible for the largest total fish biomass extraction Commercial fisheries (5,300 t per year), followed by cormorants (2,394 t per year) and recreational fishers (966 t per year). Com Human dimensions mercial fishing dominated the removals of most marine and diadromous fish, specifically herring (Clupea Conflicts Recreational fisheries harengus), while cormorants dominated the biomass extraction of smaller-bodied coastal freshwater fish, spe cifically perch (Perca fluviatilis) and roach (Rutilus rutilus). -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

Waterfowl in Iowa, Overview

STATE OF IOWA 1977 WATERFOWL IN IOWA By JACK W MUSGROVE Director DIVISION OF MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES STATE HISTORICAL DEPARTMENT and MARY R MUSGROVE Illustrated by MAYNARD F REECE Printed for STATE CONSERVATION COMMISSION DES MOINES, IOWA Copyright 1943 Copyright 1947 Copyright 1953 Copyright 1961 Copyright 1977 Published by the STATE OF IOWA Des Moines Fifth Edition FOREWORD Since the origin of man the migratory flight of waterfowl has fired his imagination. Undoubtedly the hungry caveman, as he watched wave after wave of ducks and geese pass overhead, felt a thrill, and his dull brain questioned, “Whither and why?” The same age - old attraction each spring and fall turns thousands of faces skyward when flocks of Canada geese fly over. In historic times Iowa was the nesting ground of countless flocks of ducks, geese, and swans. Much of the marshland that was their home has been tiled and has disappeared under the corn planter. However, this state is still the summer home of many species, and restoration of various areas is annually increasing the number. Iowa is more important as a cafeteria for the ducks on their semiannual flights than as a nesting ground, and multitudes of them stop in this state to feed and grow fat on waste grain. The interest in waterfowl may be observed each spring during the blue and snow goose flight along the Missouri River, where thousands of spectators gather to watch the flight. There are many bird study clubs in the state with large memberships, as well as hundreds of unaffiliated ornithologists who spend much of their leisure time observing birds. -

198 13. Repulse Bay. This Is an Important Summer Area for Seals

198 13. Repulse Bay. This is an important summer area for seals (Canadian Wildlife Service 1972) and a primary seal-hunting area for Repulse Bay. 14. Roes Welcome Sound. This is an important concentration area for ringed seals and an important hunting area for Repulse Bay. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 15. Southampton-Coats Island. The southern coastal area of Southampton Island is an important concentration area for ringed seals and is the primary ringed and bearded seal hunting area for the Coral Harbour Inuit. Fisher and Evans Straits and all coasts of Coats Island are important seal-hunting areas in late summer and early fall. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 16.7.2 Communities Affected Communities that could be affected by impacts on seal populations are Resolute and, to a lesser degree, Spence Bay, Chesterfield Inlet, and Gjoa Haven. Effects on Arctic Bay would be minor. Coral Harbour and Repulse Bay could be affected if the Quebec route were chosen. Seal meat makes up the most important part of the diet in Resolute, Spence Bay, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay. It is a secondary, but still important food in Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. Seal skins are an important source of income for Spence Bay, Resolute, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay and a less important income source for Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. 16.7.3 Data Gaps Major data gaps concerning impacts on seal populations are: 1. -

Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in USDA National Wildlife Research Center the Midwest Symposia December 1997 Review of the Population Status and Management of Double- Crested Cormorants in Ontario C. Korfanty W.G. Miyasaki J.L. Harcus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants Part of the Ornithology Commons Korfanty, C. ; Miyasaki, W.G.; and Harcus, J.L., "Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario" (1997). Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nwrccormorants/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center Symposia at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Symposium on Double- Crested Cormorants: Population Status and Management Issues in the Midwest by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Symposium on Double-Crested Cormorants 130 Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario Review of the Population Status and Management of Double-Crested Cormorants in Ontario By C. Korfanty, W. G. Miyasaki, and J. L. Harcus Abstract: We prepared this review of the status and pairs on the Canadian Great Lakes in 1997, with increasing management of double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax numbers found on inland water bodies. Double-crested auritus) in Ontario, with management options, in response to cormorants are protected in Ontario, and there are no concerns expressed about possible negative impacts of large population control programs. -

Double-Crested Cormorant Conflict Management and Research on Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report

Double-crested Cormorant Conflict Management And Research On Leech Lake 2005 Annual Report Prepared by Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Division of Resources Management Minnesota Department of Natural Resources US Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services Photo by Steve Mortensen This report summarizes cormorant conflict management and research that occurred on Leech Lake during 2005. The overall goal of this project is to determine at what level cormorant numbers can be managed for on the lake without having a significant negative effect on gamefish and on other species of colonial waterbirds that nest alongside cormorants on Little Pelican Island. Work conducted this summer went much better than anticipated and we are well on the way towards resolving cormorant conflict issues on Leech Lake. Cormorant Management Environmental Assessment An environmental assessment (EA) was prepared that gathered and evaluated information on cormorants and their effects on fish and other resources. We compiled, considered, and incorporated input from all parties that have an interest or concern about the proposed controlling of cormorants on Leech Lake. This document could have been written specifically so the Leech Lake Band could address the Leech Lake cormorant colony, but it was decided to prepare it as a joint effort between LLBO Division of Resources Management (DRM) and USDA Wildlife Services (WS), MN Department of Natural Resources (MN DNR), and US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). WS served as lead agency in this effort. By preparing it in this manner, it could be utilized by other agencies elsewhere in Minnesota if resource damage was documented. The EA proposed to reduce the Leech Lake colony more than 10% so, under provisions of the Federal Depredation Order, the Leech Lake Band submitted a request to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to go to a higher population reduction limit (reduction to 500 nests). -

Titles in This Series

Bailer animalsanimals Titles in This Series Alligators Eagles Moose Anteaters Elephants Octopuses Armadillos Foxes Owls Bats Frogs Penguins Bears Geese Pigs Bees Giraffes Porcupines Beetles Gorillas Raccoons Buffalo Hawks and Rhinoceroses Geese Butterflies Falcons Seals Camels Hippopotamuses Sharks Cats Horses Skunks Cheetahs Hummingbirds Snakes Chimpanzees Hyenas Spiders Cows Jaguars Squirrels Coyotes Jellyfish Tigers Cranes and Storks Kangaroos Turtles and Crocodiles Leopards Tortoises Deer Lions Whales Dogs Lizards Wolves Dolphins Manatees Zebras Ducks Monkeys by Darice Bailer 1st Proof Title: Animal, Animals II-Geese : 28164 Job No: PL809-105/4234 GEESE_INT_FINAL_01-48:aa buffalo interior.qxp 31/08/2009 11:09 AM Page 1 animalsanimals by Darice Bailer 1st Proof Title: Animal, Animals II-Geese : 28164 Job No: PL809-105/4234 GEESE_INT_FINAL_01-48_aa buffalo interior.qxp 2/25/10 11:29 AM Page 2 Special thanks to Donald E. Moore III, associate director of animal care at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoo, for his expert reading of this manuscript. Copyright © 2011 Marshall Cavendish Corporation Published by Marshall Cavendish Benchmark An imprint of Marshall Cavendish Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 99 White Plains Road, Tarrytown, NY 10591. Tel: (914) 332-8888, fax: (914) 332-1888. Website: www.marshallcavendish.us This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on Darice Bailer’s personal experience, knowledge, and research. -

PIELC-2016-Broshure-For-Sure.Pdf

WelcOME! Welcome to the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference (PIELC), the premier annual gathering for environmen- talists in the world! Now in its 34th year, PIELC unites thousands of activists, attorneys, students, scientists, and commu- nity members from over 50 countries to share their ideas, experience, and expertise. With keynote addresses, workshops, films, celebrations, and over 130 panels, PIELC is world-renowned for its energy, innovation, and inspiration. In 2011, PIELC received the Program of the Year Award from the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources, and in 2013 PIELC received the American Bar Assoication Law Student Division’s Public Interest Award. PIELC 2016, A LEGacY WORTH LeaVING “A Legacy Worth Leaving” is a response to the drastic need of daily, direct action of individuals in their communities. Cohesive leadership models must acknowledge that individual participation directs society’s impact on interdependent community and global systems. Diversity of cultures, talents, and specialties must converge to guide community initiatives in a balanced system. Each has a unique role that can no longer be hindered by the complacent passive-participation models of traditional leadership schemes. Building community means being community. This year at PIELC, we will be exploring alternative methods of approaching current ecological, social, and cultural paradigms. First, by examining the past – let us not relive our mistakes. Then, by focusing on the present. Days to months, months to years, years to a lifetime; small acts compound to the life-story of a person, a place, a planet. What legacy are you leaving? WIFI GUEST ACCOUNT LOGIN INSTRUCTIONS 1) Connect to the “UOguest” wireless network (do NOT connect to the “UOwireless” network). -

Schedule a Nunavut Land Use Plan Land Use Designations

65°W 70°W 60°W 75°W Alert ! 80°W 51 130 60°W Schedule A 136 82°N Nunavut Land Use Plan 85°W Land Use Designations 90°W 65°W Protected Area 82°N 95°W Special Management Area 135 134 80°N Existing Transportation Corridors 70°W 100°W ARCTIC 39 Proposed Transportation Corridors OCEAN 80°N Eureka ! 133 30 Administrative Boundaries 105°W 34 Area of Equal Use and Occupancy 110°W Nunavut Settlement Area Boundary 39 49 49 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface and Subsurface including minerals) 42 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface excluding minerals) 78°N 75°W 49 78°N 49 Established Parks (Land Use Plan does not apply) 168 168 168 168 168 168 49 49 168 39 168 168 168 168 168 168 39 168 49 49 49 39 42 39 39 44 168 39 39 39 22 167 37 70 22 18 Grise Fiord 44 18 168 58 58 49 ! 44 49 37 49 104 49 49 22 58 168 22 49 167 49 49 4918 76°N M 76°N 49 18 49 ' C 73 l u 49 28 167 r e 49 58 S 49 58 t r 49 58 a 58 59 i t 167 167 58 49 49 32 49 49 58 49 49 41 31 49 58 31 49 74 167 49 49 49 49 167 167 167 49 167 49 167 B a f f i n 49 49 167 32 167 167 167 B a y 49 49 49 49 32 49 32 61 Resolute 49 32 33 85 61 ! 1649 16 61 38 16 6138 74°N 74°N nd 61 S ou ter 61 nc as 61 61 La 75°W 20 61 69 49 49 49 49 14 49 167 49 20 49 61 61 49 49 49167 14 61 24 49 49 43 49 72°N 49 43 61 43 Pond Inlet 70°W 167 167 !49 ! 111 111 O Arctic Bay u t 167 167 e 49 26 r 49 49 29 L a 49 167 167 n 29 29 d 72°N 49 F 93 60 a Clyde River s 65°W 49 ! t 167 M ' C 60 49 I c l i e n 49 49 t 167 o c 72 k Z 49 o C h n 120°W a 70°N n e n 68°N 115°W e 49 l 49 Q i k i q t a n i 23 70°N 162 10 23 49 167 123 110°W 47 156 -

Breathing and Locomotion in Birds

Breathing and locomotion in birds. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Life Sciences. 2010 Peter George Tickle Contents Abstract 4 Declaration 5 Copyright Statement 6 Author Information 7 Acknowledgements 9 Organisation of this PhD thesis 10 Chapter 1 General Introduction 13 1. Introduction 14 1.1 The Avian Respiratory System 14 1.1.1 Structure of the lung and air sacs 16 1.1.2 Airflow in the avian respiratory system 21 1.1.3 The avian aspiration pump 25 1.2 The uncinate processes in birds 29 1.2.1 Uncinate process morphology and biomechanics 32 1.3 Constraints on breathing in birds 33 1.3.1 Development 33 1.3.2 Locomotion 35 1.3.2.1 The appendicular skeleton 35 1.3.2.2 Overcoming the trade-off between breathing 36 and locomotion 1.3.2.3 Energetics of locomotion in birds 38 1.4 Evolution of the ventilatory pump in birds 41 1.5 Overview and Thesis Aims 42 2 Chapter 2 Functional significance of the uncinate processes in birds. 44 Chapter 3 Ontogenetic development of the uncinate processes in the 45 domestic turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Chapter 4 Uncinate process length in birds scales with resting metabolic rate. 46 Chapter 5 Load carrying during locomotion in the barnacle goose (Branta 47 leucopsis): The effect of load placement and size. Chapter 6 A continuum in ventilatory mechanics from early theropods to 48 extant birds. Chapter 7 General Discussion 49 References 64 3 Abstract of a thesis by Peter George Tickle submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Life Sciences and entitled ‘Breathing and Locomotion in Birds’. -

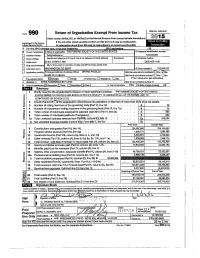

2015-Irs-Form-990.Pdf

Form 990 (2015) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . ✔ 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES’ (THE HSUS) MISSION IS TO CELEBRATE ANIMALS AND CONFRONT CRUELTY. MORE INFORMATION ON THE HSUS’S PROGRAM SERVICE ACCOMPLISHMENTS IS AVAILABLE AT HUMANESOCIETY.ORG. (SEE STATEMENT) 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 49,935,884 including grants of $ 5,456,871 ) (Revenue $ 440,435 ) EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT THE WORK OF EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT, WITH THE RELATED ACTIVITY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND COMMUNICATION TO A RANGE OF AUDIENCES, IS CONDUCTED THROUGH MANY SECTIONS INCLUDING DONOR CARE, COMPANION ANIMALS, WILDLIFE, FARM ANIMALS, COMMUNICATIONS, MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, CONFERENCES AND EVENTS, PUBLICATIONS AND CONTENT, THE HUMANE SOCIETY INSTITUTE FOR SCIENCE AND POLICY, FAITH OUTREACH, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND OUTREACH, HUMANE SOCIETY ACADEMY, CELEBRITY OUTREACH, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS. -

An Overview of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem

10–1 10.0 BIRDS Chapter Contents 10.1 F. GAVIIDAE: Loons .............................................................................................................................................10–2 10.2 F. PODICIPEDIDAE: Grebes ................................................................................................................................10–3 10.3 F. PROCELLARIIDAE: Fulmars...........................................................................................................................10–3 10.4 F. HYDROBATIDAE: Storm-petrels......................................................................................................................10–3 10.5 F. PELECANIDAE: Pelicans .................................................................................................................................10–3 10.6 F. SULIDAE: Gannets ...........................................................................................................................................10–4 10.7 F. PHALACROCORACIDAE: Cormorants............................................................................................................10–4 10.8 F. ARDEIDAE: Herons and Bitterns......................................................................................................................10–4 10.9 F. ANATIDAE: Geese, Swans, and Ducks ...........................................................................................................10–4 10.9.1 Geese............................................................................................................................................................10–5