Bones Brigade: an Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masaryk University Brno

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English language and literature The origin and development of skateboarding subculture Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. author: Jakub Mahdal Bibliography Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bachelor thesis. Brno; Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2017. NUMBER OF PAGES. The supervisor of the Bachelor thesis: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bakalářská práce. Brno; Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2017. POČET STRAN. Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Abstract This thesis analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which emerged in California in the fifties. The thesis is divided into two parts – a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part introduces the definition of a subculture, its features and functions. This part further describes American society in the fifties which provided preconditions for the emergence of new subcultures. The practical part analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which was influenced by changes in American mass culture. The end of the practical part includes an interconnection between the values of American society and skateboarders. Anotace Tato práce analyzuje vznik a vývoj skateboardové subkultury, která vznikla v padesátých letech v Kalifornii. Práce je rozdělena do dvou částí – teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část představuje pojem subkultura, její rysy a funkce. Tato část také popisuje Americkou společnost v 50. letech, jež poskytla podmínky pro vznik nových subkultur. -

1 Saltlakeunderground

SaltLakeUnderGround 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround SaltLakeUnderGround 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 22• Issue # 266 • February 2011 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Coordinator: Bethany Editor: Angela H. Brown Fischer Managing Editor: Marketing: Ischa Buchanan, Jea- Jeanette D. Moses nette D. Moses, Jessica Davis, Billy Editorial Assistant: Ricky Vigil Ditzig, Hailee Jacobson, Stephanie Action Sports Editor: Buschardt, Giselle Vickery, Veg Vol- Adam Dorobiala lum, Chrissy Hawkins, Emily Burkhart, Copy Editing Team: Jeanette D. Rachel Roller, Jeremy Riley. Moses, Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Vigil, Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Katie SLUG GAMES Coordinators: Mike Panzer, Rio Connelly, Joe Maddock, Brown, Jeanette D. Moses, Mike Reff, Alexander Ortega, Mary Enge, Kolbie Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Adam Doro- Stonehocker, Cody Kirkland, Hannah biala, Jeremy Riley, Katie Panzer, Jake Christian. Vivori, Chris Proctor, Dave Brewer, Billy Ditzig. Cover Artist: Lindsey Kuhn Issue Design: Joshua Joye Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Design Interns: Adam Dorobiala, Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Eric Sapp, Bob Plumb. Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Jesse Ad Designers: Todd Powelson, Hawlish, Nancy Burkhart, Brad Barker, Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Adam Okeefe, Manuel Aguilar, Ryan Jaleh Afshar, Lionel WIlliams, Christian Worwood, David Frohlich. Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Maggie Office Interns: Jeremy Riley, Chris Poulton, Eric Sapp, Brad Barker, KJ, Proctor. Lindsey Morris, Paden Bischoff, Mag- gie Zukowski. Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, -

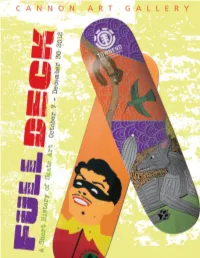

Resource Guide 4

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

Annual Report

2006 ANNUAL REPORT PAVING THE WAY TO HEALTHY COMMUNITIES Mission Statement Letter From The Founder The Tony Hawk Foundation seeks to foster lasting improvements in society, with an emphasis on supporting and Nothing slowed down in 2006. Interest in public skateparks is still empowering youth. Through special events, grants, and technical assistance, the Foundation supports recreational on the rise, and more cities than ever are stepping up to the chal- programs with a focus on the creation of public skateboard parks in low-income communities. The Foundation favors lenge of providing facilities for their youth. However, our work is far programs that clearly demonstrate that funds received will produce tangible, ongoing, positive results. from over. Unfortunately, the cities that most desperately need public skateparks are the ones that don’t have sufficient budgets. Part of Programs our job is to augment those funds, but it is more important that we provide information and ensure that parks are built right. Knowledge The primary focus of the Tony Hawk Foundation is to help facilitate the development of free, high-quality public skateparks in low-income areas by providing information is power … but funding goes a long way. and guidance on the skatepark-development process, and through financial grants. While not all skatepark projects meet our grant criteria, the Tony Hawk Foundation Over the past year, we have awarded over $340,000 to 41 communities. strives to help communities in other ways to achieve the best possible skateparks— All told, that brings us to $1.5-million and 316 grants to help build parks that will satisfy the needs of local skaters and provide them a safe, enjoyable skateparks since our inception in 2002. -

Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Up from the Street Subject: Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS RESOURCES – WEB SITES VIDEO RESOURCES BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................7 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK .........................................................................................8 Tommy Guerrero. Still image from SPARK story, February 2004. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES Up from the Street To introduce and contextualize contemporary skate culture SUBJECT To provide context for the understanding of skate Tommy Guerrero culture and contemporary music To inspire students to approach contemporary GRADE RANGES culture critically K‐12 & Post‐secondary CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS EQUIPMENT NEEDED Music & Physical Education SPARK story “Tommy Guerrero” about skateboarder and musician Tommy Guerrero on OBJECTIVES VHS or DVD and related equipment To help students ‐ Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions Opened in 1973 and Closed in 1976

Sharp Sans Display No.2 Designed By Lucas Sharp In 2015 Available In 20 Styles, Licenses For Web, Desktop & App 1 All Caps Roman POWELLPERALTA Black — 50pt BANZAI PIPELINE Extrabold — 50pt BALI INDONESIA Bold — 50pt MICKEY MUÑOZ Semibold — 50pt TSUNAMI WAVE Medium — 50pt MALIA MANUEL Book — 50pt MIKE STEWART Light — 50pt WESTWAYS CA Thin — 50pt TYLER WRIGHT Ultrathin — 50pt FREIDA ZAMBA Hairline — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 2 All Caps Oblique ROBERT WEAVER Black oblique — 50pt DENNIS HARNEY Extrabold oblique — 50pt PAUL HOFFMAN Bold oblique — 50pt NATHAN PRATT Semibold oblique — 50pt BOB SIMMONS Medium oblique — 50pt MIKE PARSONS Book oblique — 50pt JAMIE O'BRIEN Light oblique — 50pt JACK LONDON Thin oblique — 50pt KAVE KALAMA Ultrathin oblique — 50pt CRAIG STECYK Hairline oblique — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 3 All Caps Roman Lubalin Ligatures JOYCE HOFFMAN Black (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt FRED HEMMINGS Extrabold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt MATADOR BEACH Bold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt OAHU WAVE INT. Semibold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt DREW KAMPION Medium (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt ROB MACHADO Book (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt HEATHER CLARK Light (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt PAPAKOLEA BAY Thin (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt MIKE PARSONS Ultrathin (Lubalin Ligatures ) — 50pt LAIRD HAMILTON Hairline (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 4 Title Case Roman Hawaii Five-O Black — 50pt Playa Del Rey Extrabold — 50pt Fuerteventura Bold oblique — 50pt Sunny Garcia Semibold — 50pt Zephyr Team Medium — 50pt The Dogbowl Book — 50pt Pismo -

Skate Parks: a Guide for Landscape Architects and Planners

SKATE PARKS: A GUIDE FOR LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS by DESMOND POIRIER B.F.A., Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island, 1999. A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE Department of Landscape Architecture College of Regional and Community Planning KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Stephanie A. Rolley, FASLA, AICP Copyright DESMOND POIRIER 2008 Abstract Much like designing golf courses, designing and building skateboard parks requires very specific knowledge. This knowledge is difficult to obtain without firsthand experience of the sport in question. An understanding of how design details such as alignment, layout, surface, proportion, and radii of the curved surfaces impact the skateboarder’s experience is essential and, without it, a poor park will result. Skateboarding is the fastest growing sport in the US, and new skate parks are being fin- ished at a rate of about three per day. Cities and even small towns all across North America are committing themselves to embracing this sport and giving both younger and older participants a positive environment in which to enjoy it. In the interest of both the skateboarders who use them and the people that pay to have them built, it is imperative that these skate parks are built cor- rectly. Landscape architects will increasingly be called upon to help build these public parks in conjunction with skate park design/builders. At present, the relationship between landscape architects and skate park design/builders is often strained due to the gaps in knowledge between the two professions. -

Return to Form: Analyzing the Role of Media in Self-Documenting Subcultures

RETURN TO FORM: ANALYZING THE ROLE OF MEDIA IN SELF-DOCUMENTING SUBCULTURES GLEN WOOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2020 © Glen Wood, 2020 Abstract This dissertation examines self-documenting subcultures and the role of media within three case studies: hardcore punk, skateboarding, and urban dirt-bike riding. The production and distribution of subcultural media is largely governed by intracultural industries. Elite practitioners and media-makers are incentivized to document performances that are deemed essential to the preservation of the status quo. This constructed dependency reflects and reproduces an ethos of conformity that pervades both social interactions and subcultural representations. Within each self-documenting subculture, media is the primary mode of socialization and representation. The production of media and meaning is constrained by the presence of prescriptive formal conventions propagated by elite producers. These conditions, in part, result in the institutionalization of conformity. The three case studies illustrate the theoretical and methodological framework that classifies these formations under a new typology. Accordingly, this dissertation introduces an alternative approach to the study of subcultures. ii Acknowledgments My academic career is based upon the support of numerous individuals, organizations, and institutions. I would like to thank John McCullough for his inspiring words and utter confidence in my work. Moreover, Markus Reisenleitner and Steve Bailey were integral throughout the dissertation process, encouraging my progress and providing their thoughtful commentary along the way. I am also greatly appreciative of the external reviewers for their time and evaluations. -

Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity by Emily Chivers Yochim

/A7J;(?<; technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domestic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that ren- ders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technol- ogy as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focusing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publi- cations include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis- Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. -

How Did Nike Get the Swoosh Into Skateboarding? a Study of Authenticity and Nike SB

Syracuse University SURFACE S.I. Newhouse School of Public Media Studies - Theses Communications 8-2012 How Did Nike Get the Swoosh into Skateboarding? A Study of Authenticity and Nike SB Brandon Gomez Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis Part of the Marketing Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gomez, Brandon, "How Did Nike Get the Swoosh into Skateboarding? A Study of Authenticity and Nike SB" (2012). Media Studies - Theses. 3. https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies - Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Skateboarding is widely regarded as a subculture that is highly resistant to any type of integration or co-option from large, mainstream companies. In 2002 Nike entered the skateboarding market with its Nike SB line of shoes, and since 2004 has experienced tremendous success within the skateboarding culture. During its early years Nike experienced a great deal of backlash from the skateboarding community, but has recently gained wider acceptance as a legitimate company within this culture. The purpose of this study is to examine the specific aspects of authenticity Nike was able achieve in order to successfully integrate into skateboarding. In order to investigate the case of Nike SB specifically, the concept of company authenticity within skateboarding must first be clarified as well. This study involved an electronic survey of skateboarders. -

Bamcinématek Presents Skateboarding Is Not a Crime, a 24-Film Tribute to the Best of Skateboarding in Cinema, Sep 6—23

BAMcinématek presents Skateboarding is Not a Crime, a 24-film tribute to the best of skateboarding in cinema, Sep 6—23 Opens with George Gage’s 1978 Skateboard with the director in person The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Aug 16, 2013—From Friday, September 6 through Thursday, September 12, BAMcinématek presents Skateboarding is Not a Crime, a 24-film tribute to the best of skateboarding in cinema, from the 1960s to the present. The ultimate in counterculture coolness, skateboarding has made an irresistibly sexy subject for movies thanks to its rebel-athlete superstars, SoCal slacker fashion, and jaw-dropping jumps, ollies, tricks, and stunts. Opening the series on Friday, September 6 is George Gage’s Skateboard (1978), following a lumpish loser who comes up with an ill-advised scheme to manage an all-teen skateboarding team in order to settle his debts with his bookie. An awesomely retro ride through 70s skateboarding culture, Skateboard was written and produced by Miami Vice producer Dick Wolf and stars teen idol Leif Garrett (Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter plays his mom!) and Z-Boys great Tony Alva. Gage will appear in person for a Q&A following the screening. Two of the earliest films in the series showcase the upright technique that dominated in the 60s. Skaterdater (1965—Sep 23), Noel Black’s freewheelingly shot, dialogue-free puppy-love story (made with pre-adolescent members of Torrance, California’s Imperial Skateboard Club) is widely considered to be the first skateboard movie. Claude Jutra’s cinéma vérité lark The Devil’s Toy (1966—Sep 23), is narrated in faux-alarmist fashion, with kids whipping down the hills of Montreal, only to have their decks confiscated by the cops. -

Media Kit Brand Overview for the Past 37 Years, TWS Has Showcased the Finest in Skateboarding Through It’S Progressive Lens

2020 Media Kit Brand Overview For the past 37 years, TWS has showcased the finest in skateboarding through it’s progressive lens . By supporting its founding philosophy of “Skate and Create”, it procures the highest quality content via creative and talented photographers, videographers, and editors who document the innovators and influencers within skateboarding. TWS speaks to today’s skateboarder and sets an influential, authentic and authoritative voice within skate media. With one of the largest reaches in skateboarding, TWS unites a global community to promote and inspire positive growth and longevity of the sport. Total Monthly Social Monthly Audience Audience Digital Users 4.5M 3.8M 246K Percentage Database Audience Avg. HHI Male 51K $79K 86% TRANSWORLD SKATEBOARDING Unmatched digital and social reach with influential skateboard consumers from around the world. 1,749,374 1,563,044 210,431 362,000 246,075 45,177 TOTAL MONTHLY TOTAL MONTHLY TOTAL MONTHLY WEB AUDIENCE SOCIAL UNIQUES 4.5 MILLION+ 3.8 MILLION+ 246K+ DESKTOP TRAFFIC MOBILE TRAFFIC TABLET TRAFFIC 27.5% 69% 3.5% The Future For the next 12 months, TransWorld SKATEboarding has three main focuses: storytelling around skateboarding's most interesting personalities, leveraging skateboarding's most comprehensive media archive, and expanding our Digital Franchises with consistent programming. We'll activate around these focuses with a quarterly slate of documentaries, a year-long dive into past magazines and films to resurface the names, images, and segments that still move the needle, and providing seasons of shorter from Digital content and flagship franchise video edits. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● DAEWON Documentary Recap ● Documentary Film Opportunities ● Skate & Create Concept ● The History of TWS Book ● TW Skatepark Sponsorships ● “Skater’s Favorite Skater” Franchise ● “SkateHoarders” Franchise ● Digital Ad Specs DAEWON A TransWorld SKATEboarding Original Production 11M+ IMPRESSIONS 6.1% ENG.