How Did Nike Get the Swoosh Into Skateboarding? a Study of Authenticity and Nike SB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nike's Pricing and Marketing Strategies for Penetrating The

Master Degree programme in Innovation and Marketing Final Thesis Nike’s pricing and marketing strategies for penetrating the running sector Supervisor Ch. Prof. Ellero Andrea Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Camatti Nicola Graduand Sonia Vianello Matriculation NumBer 840208 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: THE NIKE BRAND & THE RUNNING SECTOR ................................................................ 6 1.1 Story of the brand..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Foundation and development ................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2 Endorsers and Sponsorships ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Sectors in which Nike currently operates .................................................................................................. 8 1.2 The running market ........................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Competitors .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.4. Strategic and marketing practices in the market ............................................................................ 21 1.5 Nike’s strengths & weaknesses ...................................................................................................... -

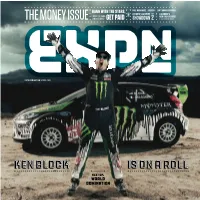

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Adidas' Bjorn Wiersma Talks Action Sports Selling

#82 JUNE / JULY 2016 €5 ADIDAS’ BJORN WIERSMA TALKS ACTION SPORTS SELLING TECHNICAL SKATE PRODUCTS EUROPEAN MARKET INTEL BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MUCH MORE TREND REPORTS: BOARDSHORTS, CAMPING & OUTDOOR, SWIMWEAR, STREETWEAR, SKATE HARDWARE & PROTECTION 1 US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson HELLO #82 [email protected] At the time of writing, Europe is finally protection and our Skateboard Editor, Dirk seeing some much needed signs of summer. Vogel looks at how the new technology skate Surf & French Editor Iker Aguirre April and May, on the whole, were wet brands are introducing into their decks, wheels [email protected] across the continent, spelling unseasonably and trucks gives retailers great sales arguments green countryside and poor spring sales for for selling high end products. We also have Senior Snowboard Contributor boardsports retail. However, now the sun our regular features; Corky from Stockholm’s shines bright and rumours are rife of El Niño’s Coyote Grind Lounge claims this issue’s Tom Wilson-North tail end heating both our oceans and air right Retailer Profile after their second place finish [email protected] the way through the summer. All is forgiven. at last year’s Vans Shop Riot series. Titus from Germany won the competition in 2015 and their Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Our business is entirely dependent on head of buying, PV Schulz gives us an insight [email protected] Mother Nature and with the Wanderlust trend into his buying tricks and tips. that’s sparked a heightened lust for travel in Millenials, spurred on by their need to document Our summer tradeshow edition is thoughtfully German Editor Anna Langer just how “at one” with nature they are, SOURCE put together to provide retailers with an [email protected] explores a new trend category in our Camping & extensive overview of SS17’s trends to assist Outdoor trend report. -

Xfbn -- New Jordans 2017 Release

xfbn - new jordans 2017 Release Chinese shoes Network March 4 hearing, talking about the Jeremy Scott Adidas shoes surgeon, and we may exaggerate their interesting designs are very deep impression, if you like that style is very keen, then this from Adidas ObyO x Jeremy Scott shoes camouflage Winnie obviously you should not miss. It's the shoe body with camouflage face cute bear for this pair of shoes add a playful taste, while the Cubs work shoes is indeed remarkable, very fine details of the office. Presumably wear it walking down the street, will keep returning soared, a friend might like to try. Japanese package decoration big PORTER will soon celebrate the 80th anniversary of the establishment, have been issued with different brands single product. Recently, PORTER and apparel brand, also from Japan, BEAUTY & amp; YOUTH co-released the latest products, the Fan joint new minimalist Japanese style design, take a blue-based colors, equipped with white zipper, issued handbags and backpacks, purses and other products. It is reported that a single product is now in BEAUTY & amp; YOUTH and ZOZOTOWN online store and shelves, and interested friends can not miss. Yeezy Boost 350 and adidas Ultra Boost is undoubtedly this summer's hot popular shoes, with Kanye West esteem and blessing, the two have become quite a good selection of shoes, shoes on the feet of the fans choose. Recently, foreign friends these two shoes shoes fans to create a new realm, to create a full one pair of hybrid footwear, reservations Yeezy Boost 350 vamp and shoe body, equipped with the Ultra Boost soles popularity recognizable shoes continues unabated, but also on foot interpretation of a lot, I wonder if you have any views on this double "half-breed" it. -

Qualifier Phoenix AM 2013 RANKNAME AGEHOMETOWN SPONSORS

Round: Qualifier Phoenix AM 2013 RANKNAME AGEHOMETOWN SPONSORS 1Bowerbank, Tyson 18 Salt Lake City, Darkstar, BC Surf and Sport, Monster, Bones, Globe, OC Ramps UT 2Estrada, Anthony 20 Los Angeles, Plan B (flow), Globe (flow), LRG (flow), Silver Trucks (flow), FKD CA (flow), ELM, Kush Pops 3Luevanos, Vincent 20 Los Angeles, Creature (flow), Independent (flow), Mob (flow), Mainline CA Skateshop, Knox Hardware, Kogi BBQ, Emerica (flow), Altamont (flow) 4Villanueva, Brendon 18 Poway, CA Powell Peralta, Neff, Bones, Bones Swiss, Gatorade, LakActive Rideshopai (flow), Fourstar (flow), Royal (flow), 5Brockel, Robbie Phoenix, AZ Real, Thunder, Spitfire, Cowtown, C1RCA, Eswic 6Zito, Austin 19 San Diego, CA Hanger 94, Foundation (flow), Dekline (flow), Ashbury Eyewear 7Serrano, Rene 12 Los Angeles, Darkstar (flow), Globe (flow), Markisa, elm, Mainline skateshop CA 8 Hart, Paul Globe (flow), Cliché, 8103 Clothing, Bones Wheels, Vestal 9Lachovski, Adriano 18 Curitiba, Brazil Warco Skateboards, Team BK (Lakai, Nixon), Fourstar, Royal, Alfa Grip, Bless Skateshop 10Lockwood, Cody 22 Portland, OR Lifeblood, Dakine, Thunder, CCs, Bones Wheels, Fallen, Jessup 11Eaton, Jagger 12 Mesa, AZ DC, Plan B, Bones Wheels, Independent,Monster, KTR 12Jordan, Dashawn 16 Chandler, AZ Darkstar, Nike (flow), KR3W (flow), Diamond (flow), Skullcandy (flow), Monster (flow), KTR 13Davis, Rayce 21 Phoenix, AZ ADDIKT Skateboards 14De Los Reyes, “Moose” 22 Oxnard, CA Deathwish, BONES Wheels, Thunder, Shakejunt, Supra, Neff 15Anaya, Anthony 16 Santa Maria, Foundation, Dekline, -

Get on Your Board and Ride! See Page 4

BCN IS YOUR LOAN WORKING FOR YOU? Point Loma Branch 4980 North Harbor Drive, Suite 202 San Diego, CA 92106 San Diego Community Newspaper Group THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 GO SKATEBOARDING DAY IS JUNE 21 INSIDE GET ON YOUR BOARD AND RIDE! SEE PAGE 4 OB Street Fair & Chili Cook-Off on June 23 SEE INSERT Point Loma High graduates 415 SEE PAGE 6 Mermaid vanishes from Sunset Cliffs Point Loma resident Brooke Young rides her Sector 9 skateboard down Newport Avenue heading to the beach. MICHELLE YOUNG / CONTRIBUTOR SEE PAGE 10 PAGE 2 | THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 | THE PENINSULA BEACON OPEN SUN 2-4 1150 Anchorage Lane #614 | 3BR/2.5BA | $995,000 3330 Dumas | 4BR/3BA | $1,299,000 COLLINS FAMILY - 619.224.0044 BETH ROACH - 619.300.0389 OPEN SUN 2-4 2301 PALERMO | 3BR/2BA | $1,100,000 3791 CEDARBRAE LANE | $1,895,000 BETH ZEDAKER - 619.602.9610 CRISTINE AND SUMMER GEE - 858.775.2222 OPEN SUN 2-4 741 ROSECRANS | 3BR/3.5BA | $4,700,000 2+BR/2BA |$1,025,000 COLLINS FAMILY - 619.224.0044 KIMBERLY PLATT - 619.248.7039 619.226.7800 | 2904 CANON STREET ANDREW E. NELSON, PRESIDENT & OWNER Meet Your Point Loma Luxury Real Estate Professionals Kimberly Platt Beth Zedaker Wendy Collins Sandy Collins Summer Crabtree Cristine Gee Narda Stroesser Vicki Droz 619.248.7039 619.602.9610 619.804.5678 619.889.5600 858.775.2222 619.980.4433 619.850.7777 619.729.8682 Jim Groak Deanna Groark Amy Alexander Cecil Shuffler Beth Roach Joan Depew Carter Shuffler Judy 619.804.3703 619.822.5222 619.917.6927 619.980.3441 619.300.0389 619.922.6155 619.884.9275 Kettenburg-Chayka 619.997.3012 THE PENINSULA BEACON | THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 | PAGE 3 COLDWELL BANKER COMING SOON WWW.4340MENTONE.COM IN ESCROW WWW.710CORDOVA.COM Ocean Beach | $399,000 Ocean Beach | $899,000 Ocean Beach | $939,000 Sunset Cliffs | $3,195,000 Not in MLS! Top floor 2br/2ba cutie w/ laminate 3 br 2.5 ba detached, turnkey home in OB. -

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Echo Publications 5-1-2007 Echo, Summer/Fall 2007 Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/echo Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Echo, Summer/Fall 2007" (2007). Echo. 23. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/echo/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Echo by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '' ,fie..y fiutve.. ut -fr/e..tidly etiv/ro Mf!..ti--r uttid --rfie/re.. yood --ro --rfie../r cv1~--r0Me..r~ . .. · ECHO STAFF features editors STORAGE TODAY? I I mare ovies I' katie a. VOSS Guaranteed Availability.... departments editors amie langus bethel swift intensecity editors mary kroeck meagan pierce staff writers brianne coulom mary kroeck matt lambert amie langus rebecca michuda frances moffett mare ovies meagan pierce joel podbereski geneisha ryland bethel swift katie a. VOSS LetAve Lt wLtVl photo/illustration editor stacy smith photographers STORAGE TODAY® jessica bloom kristen hanson ryan jacobsen mary kroeck niki miller sarah nader hans seaberg stacy smith ryan thompson katie a. VOSS Illustrators ashley bedore alana crisci hans seaberg andrew walensa ECHO SUMMER I FALL 2007 www.echomagonline.com special thanks to University Village best western hotel 500 W. Cermak Rd. Echo magazine is published twice daniel grajdura Chicago, IL 60616 a year by the Columbia College ADMINISTRATION 312-492-8001 Journalism Department. -

If the Ip Fits, Wear It: Ip Protection for Footwear--A U.S

IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR FOOTWEAR--A U.S. PERSPECTIVE Jonathan Hyman , Charlene Azema , Loni Morrow | The Trademark Reporter Document Details All Citations: 108 Trademark Rep. 645 Search Details Jurisdiction: National Delivery Details Date: November 5, 2018 at 1:16 AM Delivered By: kiip kiip Client ID: KIIPLIB Status Icons: © 2018 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR..., 108 Trademark Rep. 645 108 Trademark Rep. 645 The Trademark Reporter May-June, 2018 Article Jonathan Hyman aa1 Charlene Azema aaa1 Loni Morrow aaaa1 Copyright © 2018 by the International Trademark Association; Jonathan Hyman, Charlene Azema, Loni Morrow IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR FOOTWEAR-- A U.S. PERSPECTIVE a1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 647 A. Why IP Is Important in the Shoe Industry 648 B. Examples of Footwear Enforcement Efforts 650 II. What Types of IP Rights Are Available 658 A. Trademarks and Trade Dress 658 1. Trademarks for Footwear 658 2. Key Traits of Trademark Protection 659 3. Remedies Available Against Infringers 660 4. Duration of Protection 661 5. Trade Dress as a Category of Trademarks 662 a. Securing Trade Dress Protection 672 6. Summary of the Benefits and Limitations of Trademarks as an IP Right 680 B. Copyrights 680 1. Copyrights for Footwear 680 2. Key Traits of Copyright Protection 689 3. Duration of Protection and Copyright Ownership 691 4. Remedies Available Against Infringers 692 5. Summary of the Benefits and Limitations of Copyrights as an IP Right 693 C. -

2017 SLS Nike SB World Tour and Only One Gets the Opportunity to Claim the Title ‘SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Champion’

SLS NIKE SB WORLD TOUR: MUNICH SCHEDULE SLS 2016 1 JUNE 24, 2017 OLYMPIC PARK MUNICH ABOUT SLS Founded by pro skateboarder Rob Dyrdek in 2010, Street League Skateboarding (SLS) was created to foster growth, popularity, and acceptance of street skateboarding worldwide. Since then, SLS has evolved to become a platform that serves to excite the skateboarding community, educate both the avid and casual fans, and empower communities through its very own SLS Foundation. In support of SLS’ mission, Nike SB joined forces with SLS in 2013 to create SLS Nike SB World Tour. In 2014, the SLS Super Crown World Championship became the official street skateboarding world championship series as sanctioned by the International Skateboarding Federation (ISF). In 2015, SLS announced a long-term partnership with Skatepark of Tampa (SPoT) to create a premium global qualification system that spans from amateur events to the SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Championship. The SPoT partnership officially transitions Tampa Pro into becoming the SLS North American Qualifier that gives one non-SLS Pros the opportunity to qualify to the Barcelona Pro Open and one non-SLS Pro will become part of the 2017 World Tour SLS Pros. Tampa Pro will also serve as a way for current SLS Pros to gain extra championship qualification points to qualify to the Super Crown. SLS is now also the exclusive channel for live streaming of Tampa Pro and Tampa Am. This past March, SLS Picks 2017, Louie Lopez, took the win at Tampa Pro, gaining him the first Golden Ticket of the year straight to Super Crown. -

Masaryk University Brno

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English language and literature The origin and development of skateboarding subculture Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. author: Jakub Mahdal Bibliography Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bachelor thesis. Brno; Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2017. NUMBER OF PAGES. The supervisor of the Bachelor thesis: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bakalářská práce. Brno; Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2017. POČET STRAN. Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Abstract This thesis analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which emerged in California in the fifties. The thesis is divided into two parts – a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part introduces the definition of a subculture, its features and functions. This part further describes American society in the fifties which provided preconditions for the emergence of new subcultures. The practical part analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which was influenced by changes in American mass culture. The end of the practical part includes an interconnection between the values of American society and skateboarders. Anotace Tato práce analyzuje vznik a vývoj skateboardové subkultury, která vznikla v padesátých letech v Kalifornii. Práce je rozdělena do dvou částí – teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část představuje pojem subkultura, její rysy a funkce. Tato část také popisuje Americkou společnost v 50. letech, jež poskytla podmínky pro vznik nových subkultur. -

Page A1 Michael Reed, the Assis- Is Now the New Principal at from Page A1 the Boys & Girls Club Also Already Helped Me Find a Tant Principal at Bayshore St

EARL ON INSIDE PORT ST. LUCIE CARS Deciding how to finance your car can be difficult Page A7 Vol. 12, No. 4 Your Local News and Information Source • www.HometownNewsOL.com Friday, June 28, 2013 Freedom Need Some new faces to greet From Drug Addiction is Possible KICK THE ADDICTION WITH to know students this year SUBOXONE Private, One-on-One Consultation By Dawn Krebs sary assignments. Mimi Hoffman, the Cinema offers [email protected] In all, 16 administrative appoint- principal of Dan Addiction Alternatives LLC movie specials ments were made in St. Lucie McCarty, is now an ST. LUCIE COUNTY — As stu- County schools for the upcoming assistant principal Charles A Buscema, MD dents return to schools in August, Nova Cinemas is offering 2013-14 school year. at Fort Pierce Cen- some will be greeted by new 772-618-0505 free and $1 movies to The new changes are: tral High School. www.addictionalternativesllc.com school kids Tuesday and administrators. Deborah Iseman, the principal The principal spot Wednesday through July 24. The changes in principal of Floresta Elementary, will at Dan McCarty appointments were announced on become the assistant principal at will be filled by David 775414 Camp slots still June 19. Palm Point. Washington, the principal of Fort Her Over the last several months, Bernadette Floyd, the principal Pierce Magnet School. new assistant principal available Superintendent Michael Lannon, of St. Lucie Elementary, will now Jacqueline Lynch, the principal is Mallissa Hamilton, who was the Deputy Superintendent Genelle be the principal at Floresta Ele- at White City Elementary, will principal of Fort Pierce Westwood There are still a few Yost and the district’s executive mentary. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Fakulta Tělesné Kultury

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Fakulta tělesné kultury SPECIFICKÉ ASPEKTY UČENÍ, MOTIVACE A ADHERENCE KE SPORTOVNÍ AKTIVITĚ U SUBKULTURY BIKERŮ Disertační práce Autor: Mgr. Luděk Šebek Pracoviště: Fakulta tělesné kultury, Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Bohuslav Hodaň, CSc. Olomouc 2011 Jméno a příjmení autora: Mgr. Luděk Šebek Název disertační práce: Specifické aspekty učení, motivace a adherence ke sportovní aktivitě u subkultury bikerů Pracoviště: Katedra kinantropologie Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Bohuslav Hodaň, CSc. Rok obhajoby disertační práce: 2011 Abstrakt: V naší práci se zabýváme problematikou specifických aspektů sportovních subkultur ve vztahu k učení, motivaci a adherenci k dané pohybové aktivitě. Zkoumanou skupinou je subkultura bajkerů. Účastníky výzkumu jsou jezdci a jezdkyně ve věkovém rozpětí 17 aţ 35 let, kteří na vysoké či špičkové výkonnostní úrovni provozují downhill, tedy sjezd, downhill freeride, fourcross, slope style, freestyle a flatland biking. Sběr dat proběhl prostřednictvím focus groups, individuálních rozhovorů a zúčastněného pozorování. K zpracování dat byl pouţit program ATLAS.ti 5.0 Analýza a interpretace dat byla realizována tvorbou zakotvené teorie. Výsledkem práce teoretický model, který interpretuje zkoumané jevy jako součást procesu negociace retence a apropriace kulturního kapitálu v síti kontextuálních vztahů, které jsou tvořeny koncepty kmenové učení, lifestyle a rizikový sport. Klíčová slova: Subkultura, biker, riziko, situované učení, apropriace, identita. Souhlasím s vypůjčováním disertační práce v rámci knihovních sluţeb. 2 Author’s first name and surname: Mgr. Luděk Šebek Title of the doctoral thesis: Specific aspects of learning, motivation and adherence to sport activity within the subculture of bikers Department: Department of Kinantropology Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Bohuslav Hodaň, CSc. The year of presentation: 2011 Abstract: This paper represents a qualitative study of specific aspects of learning, motivation and adherence to sport activity.