A Critical Discourse Analysis of Patriarchal Menstruation Discourse Kathryn M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1

THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. 32, No. 1 THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1 Published by the University of Nicosia ISSN 1015-2881 (Print) | ISSN 2547-8974 (Online) P.O. Box 24005 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus T: 22-842301, 22-841500 E: [email protected] www.cyprusreview.org SUBSCRIPTION OFFICE: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2020 University of Nicosia, Cyprus ISSN 1015-2881 (Print), 2547-8974 (Online) DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles All rights reserved. and reviews published in this journal No restrictions on photo-copying. are those of the authors and do Quotations from The Cyprus Review not necessarily represent the views are welcome, but acknowledgement of the University of Nicosia, the Editorial Board, or the Editors. of the source must be given. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief: Dr Christina Ioannou Consulting Editor: Prof. Achilles C. Emilianides Managing Editor: Dr Emilios A. Solomou Publications Editor: Dimitrios A. Kourtis Assistant Editor: Dr Maria Hadjiathanasiou Copy Editor: Mary Kammitsi Publication Designer: Thomas Costi EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Constantinos Adamides University of Nicosia Prof. Panayiotis Angelides University of Nicosia Dr Odysseas Christou University of Nicosia Prof. Costas M. Constantinou University of Cyprus Prof. Dimitris Drikakis University of Nicosia Prof. Hubert Faustmann University of Nicosia EDITORIAL Dr Sofia Iordanidou Open University of Cyprus Prof. Andreas Kapardis University of Cyprus -

The Potential of Leaks: Mediation, Materiality, and Incontinent Domains

THE POTENTIAL OF LEAKS: MEDIATION, MATERIALITY, AND INCONTINENT DOMAINS ALYSSE VERONA KUSHINSKI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2019 © Alysse Kushinski, 2019 ABSTRACT Leaks appear within and in between disciplines. While the vernacular implications of leaking tend to connote either the release of texts or, in a more literal sense, the escape of a fluid, the leak also embodies more poetic tendencies: rupture, release, and disclosure. Through the contours of mediation, materiality, and politics this dissertation traces the notion of “the leak” as both material and figurative actor. The leak is a difficult subject to account for—it eludes a specific discipline, its meaning is fluid, and its significance, always circumstantial, ranges from the entirely banal to matters of life and death. Considering the prevalence of leakiness in late modernity, I assert that the leak is a dynamic agent that allows us to trace the ways that actors are entangled. To these ends, I explore several instantiations of “leaking” in the realms of media, ecology, and politics to draw connections between seemingly disparate subjects. Despite leaks’ threatening consequences, they always mark a change, a transformation, a revelation. The leak becomes a means through which we can challenge ourselves to reconsider the (non)functionality of boundaries—an opening through which new possibilities occur, and imposed divisions are contested. However, the leak operates simultaneously as opportunity and threat—it is always a virtual agent, at once stagnant and free flowing. -

Menstruation Regulation: a Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2020 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram Max Faust Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Communication Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Faust, Max, "Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 576. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/576 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 1 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram By Max Faust An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College College of Arts and Sciences East Tennessee State University ___________________________________________ Max Faust Date ___________________________________________ Dr. C. Wesley Buerkle, Thesis Mentor Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Kelly A. Dorgan, Reader Date FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 2 Abstract Much research about advertisements for menstrual products reveals the ways in which such advertising perpetuates shame and reinforces unrealistic ideals of femininity and womanhood. -

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain A Research Paper presented by: Claudia Lucía Arbeláez Orjuela (Colombia) in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Policy for Development SPD Members of the Examining Committee: Wendy Harcourt Rosalba Icaza The Hague, The Netherlands November 2017 ii A mis padres iii Contents List of Appendices vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Research question 4 1.2. Structure 4 Chapter 2 Some Voices to rely on 5 2.1. Entry point: Menstrual Activism 6 2.2. Corporeal feminism 7 2.3. Body Politics 8 Chapter 3 The Setting 10 3. 1. Exploring the menstrual cultures in Contemporary Spain 10 3.2. Activist and feminist Barcelona 11 Chapter 4 Methodology 14 4.1. Embodied Knowledges: A critical position from feminist epistemology 14 4.2. Semi-structured Interviews 15 4.3. Ethnography and Participant observation 16 4.4. Netnography 16 Chapter 5 Let it Bleed: Art, Policy and Campaigns 17 5.1. Menstruation and Art 17 5.1.1 Radical Menstruators 17 5.1.2. Lola Vendetta and Zinteta: glittery menstruation and feminism(s) for millenials. 20 5.2. ‘Les Nostres Regles’ 23 5.3. Policy 25 5.3.1. EndoCataluña 25 iv 5.3.2. La CUP’s Motion 26 Chapter 6 Menstrual Education: lessons from the embodied experience 29 6.1. Divine Menstruation – A Natural Gynaecology Workshop 31 6.2. Somiarte 32 6.3. Erika Irusta and SOY1SOY4 34 Chapter 7 Sustainable menstruation: ecological awareness and responsible consumption 38 7.1. -

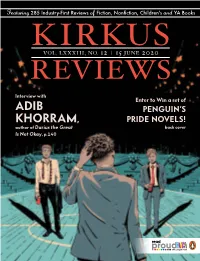

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Menstrual Justice

Menstrual Justice Margaret E. Johnson* Menstrual injustice is the oppression of menstruators, women, girls, transgender men and boys, and nonbinary persons, simply because they * Copyright © 2019 Margaret E. Johnson. Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center on Applied Feminism, Director, Bronfein Family Law Clinic, University of Baltimore School of Law. My clinic students and I have worked with the Reproductive Justice Coalition on legislative advocacy for reproductive health care policies and free access to menstrual products for incarcerated persons since fall 2016. In 2018, two bills became law in Maryland requiring reproductive health care policies in the correctional facilities as well as free access to products. Maryland HB 787/SB629 (reproductive health care policies) and HB 797/SB 598 (menstrual products). I want to thank the Coalition members and my students who worked so hard on these important laws and are currently working on their implementation and continued reforms. I also want to thank the following persons who reviewed and provided important feedback on drafts and presentations of this Article: Professors Michele Gilman, Shanta Trivedi, Virginia Rowthorn, Nadia Sam-Agudu, MD, Audrey McFarlane, Lauren Bartlett, Carolyn Grose, Claire Donohue, Phyllis Goldfarb, Tanya Cooper, Sherley Cruz, Naomi Mann, Dr. Nadia Sam-Agudu, Marcia Zug, Courtney Cross, and Sabrina Balgamwalla. I want to thank Amy Fettig for alerting me to the breadth of this issue. I also want to thank Bridget Crawford, Marcy Karin, Laura Strausfeld, and Emily Gold Waldman for collaborating and thinking about issues relating to periods and menstruation. And I am indebted to Max Johnson-Fraidin for his insight into the various critical legal theories discussed in this Article and Maya Johnson-Fraidin for her work on menstrual justice legislative advocacy. -

Leslie White (1900-1975)

Neoevolutionism Leslie White Julian Steward Neoevolutionism • 20th century evolutionists proposed a series of explicit, scientific laws liking cultural change to different spheres of material existence. • Although clearly drawing upon ideas of Marx and Engels, American anthropologists could not emphasize Marxist ideas due to reactionary politics. • Instead they emphasized connections to Tylor and Morgan. Neoevolutionism • Resurgence of evolutionism was much more apparent in U.S. than in Britain. • Idea of looking for systematic cultural changes through time fit in better with American anthropology because of its inclusion of archaeology. • Most important contribution was concern with the causes of change rather than mere historical reconstructions. • Changes in modes of production have consequences for other arenas of culture. • Material factors given causal priority Leslie White (1900-1975) • Personality and Culture 1925 • A Problem in Kinship Terminology 1939 • The Pueblo of Santa Ana 1942 • Energy and the Evolution of Culture 1943 • Diffusion Versus Evolution: An Anti- evolutionist Fallacy 1945 • The Expansion of the Scope of Science 1947 • Evolutionism in Cultural Anthropology: A Rejoinder 1947 • The Science of Culture 1949 • The Evolution of Culture 1959 • The Ethnology and Ethnography of Franz Boas 1963 • The Concept of Culture 1973 Leslie White • Ph.D. dissertation in 1927 on Medicine Societies of the Southwest from University of Chicago. • Taught by Edward Sapir. • Taught at University of Buffalo & University of Michigan. • Students included Marshall Sahlins and Elman Service. • A converted Boasian who went back to Morgan’s ideas of evolutionism after reading League of the Iroquois. • Culture is based upon symbols and uniquely human ability to symbolize. • White calls science of culture "culturology" • Claims that "culture grows out of culture" • For White, culture cannot be explained biologically or psychologically, but only in terms of itself. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Barack Obama Speeches Vis-À-Vis

A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF BARACK OBAMA’S SPEECHES VIS-A-VIS MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA By Alelign Aschale PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics and Communication Addis Ababa University June 2013 Addis Ababa ~ ㄱ ~ Table of Contents Contents Pages Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Key to Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................... ii 1. A Brief Introduction on Critical Discourse Analysis ............................................................................ 1 2. Objectives of the Study ......................................................................................................................... 5 3. Research Questions ............................................................................................................................... 5 4. The Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) Analytical Framework Employed in the Study ..................... 6 5. Rational of the Speeches Selected for Analysis .................................................................................... 7 6. A Brief Profile of Barack Hussein Obama ............................................................................................ 7 7. The Critical Discourse Analysis of Barack Hussein Obama‘s Selected Speeches ............................... 8 7.1. Narrating Morality and Religion .................................................................................................. -

Technologies of Menstrual Management in Nineteenth-Century America

AMERICA’S BLOODY HISTORY: MENSTRUATION MANAGEMENT IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY by Tess Frydman A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2018 © 2018 Tess Frydman All Rights Reserved AMERICA’S BLOODY HISTORY: MENSTRUATION MANAGEMENT IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY by Tess Frydman Approved: __________________________________________________________ Rebecca Davis, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Wendy Bellion, Ph.D. Acting Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I wish to express my sincere thanks to my advisor, Rebecca Davis, who has given so freely of her time to guide me through this process. Her advice, painstaking edits, encouragement, and support are deeply appreciated. I also gratefully acknowledge the support and generosity of The Coco Kim Scholarship and the Winterthur Program Professional Development Funds, without which this research could not have been completed. I am also incredibly thankful to those who have opened their archives, libraries, and collections to me. Harry Finley, founder of the Museum of Menstruation, initially sparked my interest in this subject and allowed me to explore his incredible collection of menstrual ephemera. Patricia Edmonson of the Western Reserve Historical Society provided advice and let me explore numerous undergarments in the historical society’s collection. -

Cognitive Mapping of the Contemporary German Matrimonial Confrontational Discourse

© 2019 Lege artis. Language yesterday, today, tomorrow Research article LEGE ARTIS Language yesterday, today, tomorrow Vol. IV. No 2 2019 COGNITIVE MAPPING OF THE CONTEMPORARY GERMAN MATRIMONIAL CONFRONTATIONAL DISCOURSE Iryna Osovska*, Liudmyla Tomniuk Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, Chernivtsi, Ukraine *Corresponding author Bibliographic description: Osovska, I. & Tomniuk, L. (2019). Cognitive mapping of the contemporary German matrimonial confrontational discourse. In Lege artis. Language yesterday, today, tomorrow. The journal of University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. Trnava: University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, 2019, IV (2), December 2019, p. 168-215. ISSN 2453-8035 Abstract: The article presents a method of cognitive mapping using an example of reconstruction of conceptual system of contemporary German matrimonial confrontational discourse that reproduces collective cognitive space of German matrimonial couples. The basic principle of the proposed methodology allows following up a holistic mental representation of this segment of family discourse in a statistically verified conceptual structure and the system of correlations between its elements. Key words: discourse practice, family discourse, matrimonial discourse, confrontational communication, conceptual system, cognitive space, collective cognitive space, linguoquantitative method. 1. Introduction Present-day linguistic studies are focused on systemic organization of the individual's thinking. As Prihodko and Prykhodchenko claim, "cognitive processes in our mind are usually connected with our vision and understanding of outer world in general and our place in it in particular" (2018: 164). Mental background of any activity is reconstructed by researchers as both separate concepts containing specified knowledge, conceptual spheres, and fields united by common logical-semantic or substantive content, and conceptual systems as discursive-relevant formations of concepts representing certain relevant spaces of an individual. -

Sociology/Lesson 14 Subcultures & Countercultures April 9, 2020

ISD Virtual Learning Sociology/Lesson 14 Subcultures & Countercultures April 9, 2020 Sociology Lesson: April 9, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: The student will explain the difference between subcultures & countercultures. Warm Up: Review: What is culture? Think back to previous lessons or topics we have covered. On a sheet of paper, write down your own definition of culture. Can you think of any people who don’t fit into the dominant group of culture? Any people that may not share the same characteristics with the majority of people in the culture? If so, jot your ideas down on the same sheet of paper. Warm Up: Review: What is culture? Think back to previous lessons or topics we have covered. On a sheet of paper, write down your own definition of culture. Can you think of any people who don’t fit into I know that culture is made up of the the dominant group of culture? Any people that knowledge, values, beliefs, customs and may not share the same characteristics with the objects (material culture) that is shared by majority of people in the culture? If so, jot your members of a society. ideas down on the same sheet of paper. Lesson Activity: Subculture-Any group that exists within dominant, mainstream culture… “a world within a world.” Today we are going to learn about subcultures Subcultures have: and countercultures. –Shared ideology…values, norms, beliefs Please familiarize yourself with the following –Shared aesthetic…dress, pastimes, music, vocabulary, and refer back to this slide as zines/blogs, etc. needed: –Shared vernacular…specialized language Culture- includes knowledge, values, customs, & physical objects (material culture) that are Counterculture-A group whose values and norms shared by members of a society. -

Urban Cultural Space in the Context of Evolutionism

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 9, No. 1, March 2020 DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v9i1.2481 Citation: Freidlina, V., & Uvarova, T. (2020). Urban Cultural Space in the Context of Evolutionism. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 9(1), 458-467. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v9i1.2481 Urban Cultural Space in the Context of Evolutionism Viktoriia Freidlina1, Tetiana Uvarova2 Abstract Attempts to determine the essence of urban culture were made in the framework of different approaches: civilizational, philosophical, anthropological, sociological, and others. This article is concerned with the analysis of the urban cultural space phenomenon from the evolutionary point of view. Originating as the first ethnographic theory in the works of German historian Friedrich Gustav Klemm, cultural evolutionism was further developed in the evolutionary theory of cultural development, the founder of which is the English ethnologist Edward Burnett Tylor. The problems of the evolutionary theory of culture were widely discussed in scientific circles and found common ground with such ideas as the “axial age” concept by Karl Jaspers and the doctrine of the noosphere. Some common points in understanding the synergistic mechanisms of cultural activities can be found in the holistic "philosophy of integrity". An evolutionary analysis of urban cultural space remains relevant today. In this article, we analyze the possibility of studying the processes of cultural transformation in the context of changes in the forms of joint social life, developing from the incoherent homogeneous structure of ancient human settlements to the complex heterogeneous structure of modern highly urbanized urban communities.