She Got Her Period: Men's Knowledge and Perspectives on Menstruation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1

THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. 32, No. 1 THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1 Published by the University of Nicosia ISSN 1015-2881 (Print) | ISSN 2547-8974 (Online) P.O. Box 24005 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus T: 22-842301, 22-841500 E: [email protected] www.cyprusreview.org SUBSCRIPTION OFFICE: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2020 University of Nicosia, Cyprus ISSN 1015-2881 (Print), 2547-8974 (Online) DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles All rights reserved. and reviews published in this journal No restrictions on photo-copying. are those of the authors and do Quotations from The Cyprus Review not necessarily represent the views are welcome, but acknowledgement of the University of Nicosia, the Editorial Board, or the Editors. of the source must be given. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief: Dr Christina Ioannou Consulting Editor: Prof. Achilles C. Emilianides Managing Editor: Dr Emilios A. Solomou Publications Editor: Dimitrios A. Kourtis Assistant Editor: Dr Maria Hadjiathanasiou Copy Editor: Mary Kammitsi Publication Designer: Thomas Costi EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Constantinos Adamides University of Nicosia Prof. Panayiotis Angelides University of Nicosia Dr Odysseas Christou University of Nicosia Prof. Costas M. Constantinou University of Cyprus Prof. Dimitris Drikakis University of Nicosia Prof. Hubert Faustmann University of Nicosia EDITORIAL Dr Sofia Iordanidou Open University of Cyprus Prof. Andreas Kapardis University of Cyprus -

The Potential of Leaks: Mediation, Materiality, and Incontinent Domains

THE POTENTIAL OF LEAKS: MEDIATION, MATERIALITY, AND INCONTINENT DOMAINS ALYSSE VERONA KUSHINSKI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2019 © Alysse Kushinski, 2019 ABSTRACT Leaks appear within and in between disciplines. While the vernacular implications of leaking tend to connote either the release of texts or, in a more literal sense, the escape of a fluid, the leak also embodies more poetic tendencies: rupture, release, and disclosure. Through the contours of mediation, materiality, and politics this dissertation traces the notion of “the leak” as both material and figurative actor. The leak is a difficult subject to account for—it eludes a specific discipline, its meaning is fluid, and its significance, always circumstantial, ranges from the entirely banal to matters of life and death. Considering the prevalence of leakiness in late modernity, I assert that the leak is a dynamic agent that allows us to trace the ways that actors are entangled. To these ends, I explore several instantiations of “leaking” in the realms of media, ecology, and politics to draw connections between seemingly disparate subjects. Despite leaks’ threatening consequences, they always mark a change, a transformation, a revelation. The leak becomes a means through which we can challenge ourselves to reconsider the (non)functionality of boundaries—an opening through which new possibilities occur, and imposed divisions are contested. However, the leak operates simultaneously as opportunity and threat—it is always a virtual agent, at once stagnant and free flowing. -

Menstruation Regulation: a Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2020 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram Max Faust Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Communication Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Faust, Max, "Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 576. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/576 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 1 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram By Max Faust An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College College of Arts and Sciences East Tennessee State University ___________________________________________ Max Faust Date ___________________________________________ Dr. C. Wesley Buerkle, Thesis Mentor Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Kelly A. Dorgan, Reader Date FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 2 Abstract Much research about advertisements for menstrual products reveals the ways in which such advertising perpetuates shame and reinforces unrealistic ideals of femininity and womanhood. -

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain A Research Paper presented by: Claudia Lucía Arbeláez Orjuela (Colombia) in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Policy for Development SPD Members of the Examining Committee: Wendy Harcourt Rosalba Icaza The Hague, The Netherlands November 2017 ii A mis padres iii Contents List of Appendices vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Research question 4 1.2. Structure 4 Chapter 2 Some Voices to rely on 5 2.1. Entry point: Menstrual Activism 6 2.2. Corporeal feminism 7 2.3. Body Politics 8 Chapter 3 The Setting 10 3. 1. Exploring the menstrual cultures in Contemporary Spain 10 3.2. Activist and feminist Barcelona 11 Chapter 4 Methodology 14 4.1. Embodied Knowledges: A critical position from feminist epistemology 14 4.2. Semi-structured Interviews 15 4.3. Ethnography and Participant observation 16 4.4. Netnography 16 Chapter 5 Let it Bleed: Art, Policy and Campaigns 17 5.1. Menstruation and Art 17 5.1.1 Radical Menstruators 17 5.1.2. Lola Vendetta and Zinteta: glittery menstruation and feminism(s) for millenials. 20 5.2. ‘Les Nostres Regles’ 23 5.3. Policy 25 5.3.1. EndoCataluña 25 iv 5.3.2. La CUP’s Motion 26 Chapter 6 Menstrual Education: lessons from the embodied experience 29 6.1. Divine Menstruation – A Natural Gynaecology Workshop 31 6.2. Somiarte 32 6.3. Erika Irusta and SOY1SOY4 34 Chapter 7 Sustainable menstruation: ecological awareness and responsible consumption 38 7.1. -

The Cultural Learning Process : Diffusion Versus Evolution

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1979 The cultural learning process : diffusion versus evolution. Paul Shao University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Shao, Paul, "The cultural learning process : diffusion versus evolution." (1979). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3539. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3539 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURAL LEARNING PROCESS; DIFFUSION VERSUS EVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented By PAUL PONG WAH SHAO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1979 Education Paul Shao 1978 © All Rights Reserved THE CULTURAL LEARNING PROCESS: DIFFUSION VERSUS EVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented By PAUL PONG WAH SHAO Approved as to style and content by: ABSTRACT The Cultural Learning Process: Diffusion Versus Evolution February, 1979 Paul Shao, B.A., China Art College M.F.A., University of Massachusetts Ed. D., University of Massachusetts Directed By: Professor Daniel C. Jordan Purpose of the Study This study attempts to shed -

Tourism and Cultural Identity: the Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 101-120 Tourism and Cultural Identity: The Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center By Jeffery M. Caneen Since Boorstein (1964) the relationship between tourism and culture has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. This paper reviews the debate and contrasts it with the anthropological focus on cultural invention and identity. A model is presented to illustrate the relationship between the image of authenticity perceived by tourists and the cultural identity felt by indigenous hosts. A case study of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, USA exemplifies the model’s application. This paper concludes that authenticity is too vague and contentious a concept to usefully guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. It recommends, rather that preservation and enhancement of identity should be their focus. Keywords: culture, authenticity, identity, Pacific, tourism Introduction The aim of this paper is to propose a new conceptual framework for both understanding and managing the impact of tourism on indigenous host culture. In seminal works on tourism and culture the relationship between the two has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. But as Prideaux, et. al. have noted: “authenticity is an elusive concept that lacks a set of central identifying criteria, lacks a standard definition, varies in meaning from place to place, and has varying levels of acceptance by groups within society” (2008, p. 6). While debating the metaphysics of authenticity may have merit, it does little to guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. -

Traversing the Ridge: Connecting Menstrual Research and Advocacy

23rd Biennial Conference of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research Traversing the Ridge: Connecting Menstrual Research and Advocacy Colorado Springs, CO June 6 - 8, 2019 Full Conference Schedule & Abstracts: Thursday 6th June 2:00 pm Bemis Lounge Registrations Opens 3:00 pm – 4:30 pm Tutt Science Bldg (TSB) Concurrent Workshop (CW) Sessions #1 CW 1.1: How to Teach Cervical Mucus in Menstrual Health Education TSB Rm. 218 Lisa Leger, Justisse College International, Canada Sexual health education teaches about menstruation, contraception, and STI’s, but usually lacks a coherent strategy for teaching about cervical mucus and other symptoms that the cycling body experiences. This session is intended as training on how to teach about the meaning and usefulness of cervical mucus observations so your clients get a more full picture about what occurs in the female body and how to interpret their observations. Justisse Holistic Reproductive Health Practitioners will explain how to talk about vaginal fluids to reassure clients that it is something normal, healthy, and actually useful to be aware of. This session will review how to handle questions about what clients see in their underwear or on the toilet tissue and the pros and cons of internal checks. You will learn how to field such questions and use them as teachable moments to elaborate on how Fertility Awareness Methods work, the benefits of being aware of cycles, and how such observations can be used as a health record and diagnostic tool. Learn how to explain the ways in which cervical mucus differs from vaginal cell slough, yeast infection, Bacterial Vaginosis, or arousal fluid. -

Nepal's Menstrual Movement

Implemented by: In Cooperation with: NEPAL’S MENSTRUAL MOVEMENT How ‘MenstruAction’ is making life better for girls and women in Nepal — month after month 1 FOREWORD ROLAND SCHÄFER, GERMAN AMBASSADOR TO NEPAL 03 FOREWORD DR. PUSHPA CHAUDHARY 05 FOREWORD DR. MARNI SOMMER 06 INTRODUCTION 07 THE ANCIENT PRACTICE OF CHHAUPADI 08 THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM: SOME FACTS AND FIGURES 10 Content Practice of Chhaupadi 11 Menstruation product access and usage 11 Other restrictions 12 Sanitation 13 THE STORY SO FAR 14 Right to informed choice 17 Moving the MHM agenda forward 18 Working together through the MHM Practitioner Alliance 19 MENSTRUACTIVISTS. SOME MOVERS AND SHAKERS BEHIND MHM 20 MHM is the biggest topic around 21 The need for better data and understanding of the issues 23 Reflecting on restrictive practices through film making 25 Five Days 27 WATER AND SANITATION. THE KEY TO BETTER MENSTRUAL HYGIENE 28 Nepal’s geography is the biggest challenge 29 Addressing menstrual issues through WASH programmes 31 EDUCATION TO TACKLE TABOOS 32 The government is incorporating MHM issues into the school curriculum 33 AWARENESS AND EDUCATION IN ACTION: THE EXAMPLE OF BIDUR MUNICIPALITY 34 Raising awareness about menstrual health and hygiene management 35 Allocating resources to schools for MHM 36 Working with young people 38 Using radio to break down taboos 39 INVENTIONS, INNOVATIONS AND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS 40 Producing low cost sanitary pads 41 Homemade eco-friendly, reusable cloth sanitary pads 42 ‘Wake Up, Kick Ass’ 43 Nepal’s first sanitary napkin -

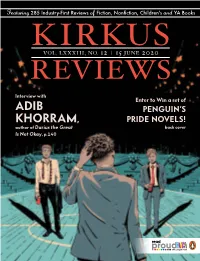

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Menstrual Justice

Menstrual Justice Margaret E. Johnson* Menstrual injustice is the oppression of menstruators, women, girls, transgender men and boys, and nonbinary persons, simply because they * Copyright © 2019 Margaret E. Johnson. Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center on Applied Feminism, Director, Bronfein Family Law Clinic, University of Baltimore School of Law. My clinic students and I have worked with the Reproductive Justice Coalition on legislative advocacy for reproductive health care policies and free access to menstrual products for incarcerated persons since fall 2016. In 2018, two bills became law in Maryland requiring reproductive health care policies in the correctional facilities as well as free access to products. Maryland HB 787/SB629 (reproductive health care policies) and HB 797/SB 598 (menstrual products). I want to thank the Coalition members and my students who worked so hard on these important laws and are currently working on their implementation and continued reforms. I also want to thank the following persons who reviewed and provided important feedback on drafts and presentations of this Article: Professors Michele Gilman, Shanta Trivedi, Virginia Rowthorn, Nadia Sam-Agudu, MD, Audrey McFarlane, Lauren Bartlett, Carolyn Grose, Claire Donohue, Phyllis Goldfarb, Tanya Cooper, Sherley Cruz, Naomi Mann, Dr. Nadia Sam-Agudu, Marcia Zug, Courtney Cross, and Sabrina Balgamwalla. I want to thank Amy Fettig for alerting me to the breadth of this issue. I also want to thank Bridget Crawford, Marcy Karin, Laura Strausfeld, and Emily Gold Waldman for collaborating and thinking about issues relating to periods and menstruation. And I am indebted to Max Johnson-Fraidin for his insight into the various critical legal theories discussed in this Article and Maya Johnson-Fraidin for her work on menstrual justice legislative advocacy. -

Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: a Narrative Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review Kathryn Holmes 1,* , Christina Curry 1, Sherry 1 , Tania Ferfolja 1, Kelly Parry 2, Caroline Smith 2,3, Mikayla Hyman 2 and Mike Armour 2,3 1 Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (S.); [email protected] (T.F.) 2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (M.A.) 3 Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64247360252 Abstract: Background: Poor menstrual health literacy impacts adolescents’ quality of life and health outcomes across the world. The aim of this systematic review was to identify concerns about menstrual health literacy in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs). Methods: Relevant social science and medical databases were searched for peer-reviewed papers published from January 2008 to January 2020, leading to the identification of 61 relevant studies. Results: A thematic analysis of the data revealed that LMICs report detrimental impacts on Citation: Holmes, K.; Curry, C.; adolescents in relation to menstrual hygiene and cultural issues, while in HICs, issues related to pain Sherry; Ferfolja, T.; Parry, K.; Smith, C.; Hyman, M.; Armour, M. -

Field Bulletin

Issue No.: 01; April 2011 United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office FIELD BULLETIN Chaupadi In The Far-West Background Chaupadi is a long held and widespread practice in the Far and Mid Western Regions of Nepal among all castes and groups of Hindus. According to the practice, women are considered ‘impure’ during their menstruation cycle, and are subsequently separated from others in many spheres of normal, daily life. The system is also known as ‘chhue’ or ‘bahirhunu’ in Dadeldhura, Baitadi and Darchula, as ‘chaupadi’ in Achham, and as ‘chaukulla’ or ‘chaukudi’ in Bajhang district. Participants of training on Chaupadi-WCDO Doti Discrimination Against Women During Menstruation According to the Accham Women’s Development Officer (WDO), more Women face various discriminatory practices in the context of than 95% of women are practicing chaupadi. The tradition is that women cannot enter inside houses, chaupadi in the district. Women kitchens and temples. They also can’t touch other persons, cattle, and Child Development Offices in green vegetables and plants, or fruits. Similarly, women practicing Doti and Achham are chaupadi cannot milk buffalos or cows, and are not allowed to drink implementing an ‘Awareness milk or eat milk products. Programme against Chaupadi’. The programme is supported by Save Generally, women stay in a separate hut or cattle shed for 5 days the Children and covers 19 VDCs in during menstruation. However, those experiencing menstruation for Achham and 10 VDCs in Doti.In the the first time should, according to practice, remain in such a shed for VDCs targeted by this program, the at least 14 days.