The Potential of Leaks: Mediation, Materiality, and Incontinent Domains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1

THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. 32, No. 1 THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1 Published by the University of Nicosia ISSN 1015-2881 (Print) | ISSN 2547-8974 (Online) P.O. Box 24005 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus T: 22-842301, 22-841500 E: [email protected] www.cyprusreview.org SUBSCRIPTION OFFICE: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2020 University of Nicosia, Cyprus ISSN 1015-2881 (Print), 2547-8974 (Online) DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles All rights reserved. and reviews published in this journal No restrictions on photo-copying. are those of the authors and do Quotations from The Cyprus Review not necessarily represent the views are welcome, but acknowledgement of the University of Nicosia, the Editorial Board, or the Editors. of the source must be given. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief: Dr Christina Ioannou Consulting Editor: Prof. Achilles C. Emilianides Managing Editor: Dr Emilios A. Solomou Publications Editor: Dimitrios A. Kourtis Assistant Editor: Dr Maria Hadjiathanasiou Copy Editor: Mary Kammitsi Publication Designer: Thomas Costi EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Constantinos Adamides University of Nicosia Prof. Panayiotis Angelides University of Nicosia Dr Odysseas Christou University of Nicosia Prof. Costas M. Constantinou University of Cyprus Prof. Dimitris Drikakis University of Nicosia Prof. Hubert Faustmann University of Nicosia EDITORIAL Dr Sofia Iordanidou Open University of Cyprus Prof. Andreas Kapardis University of Cyprus -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Menstruation Regulation: a Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2020 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram Max Faust Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Communication Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Faust, Max, "Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 576. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/576 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 1 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram By Max Faust An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College College of Arts and Sciences East Tennessee State University ___________________________________________ Max Faust Date ___________________________________________ Dr. C. Wesley Buerkle, Thesis Mentor Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Kelly A. Dorgan, Reader Date FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 2 Abstract Much research about advertisements for menstrual products reveals the ways in which such advertising perpetuates shame and reinforces unrealistic ideals of femininity and womanhood. -

The Views of the U.S. Left and Right on Whistleblowers Whistleblowers on Right and U.S

The Views of the U.S. Left and Right on Whistleblowers Concerning Government Secrets By Casey McKenzie Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Erin Kristin Jenne Word Count: 12,868 CEU eTD Collection Budapest Hungary 2014 Abstract The debates on whistleblowers in the United States produce no simple answers and to make thing more confusing there is no simple political left and right wings. The political wings can be further divided into far-left, moderate-left, moderate-right, far-right. To understand the reactions of these political factions, the correct political spectrum must be applied. By using qualitative content analysis of far-left, moderate-left, moderate-right, far-right news sites I demonstrate the debate over whistleblowers belongs along a establishment vs. anti- establishment spectrum. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgments I would like to express my fullest gratitude to my supervisor, Erin Kristin Jenne, for the all the help see gave me and without whose guidance I would have been completely lost. And to Danielle who always hit me in the back of the head when I wanted to give up. CEU eTD Collection ii Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgments..................................................................................................................... -

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain A Research Paper presented by: Claudia Lucía Arbeláez Orjuela (Colombia) in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Policy for Development SPD Members of the Examining Committee: Wendy Harcourt Rosalba Icaza The Hague, The Netherlands November 2017 ii A mis padres iii Contents List of Appendices vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Research question 4 1.2. Structure 4 Chapter 2 Some Voices to rely on 5 2.1. Entry point: Menstrual Activism 6 2.2. Corporeal feminism 7 2.3. Body Politics 8 Chapter 3 The Setting 10 3. 1. Exploring the menstrual cultures in Contemporary Spain 10 3.2. Activist and feminist Barcelona 11 Chapter 4 Methodology 14 4.1. Embodied Knowledges: A critical position from feminist epistemology 14 4.2. Semi-structured Interviews 15 4.3. Ethnography and Participant observation 16 4.4. Netnography 16 Chapter 5 Let it Bleed: Art, Policy and Campaigns 17 5.1. Menstruation and Art 17 5.1.1 Radical Menstruators 17 5.1.2. Lola Vendetta and Zinteta: glittery menstruation and feminism(s) for millenials. 20 5.2. ‘Les Nostres Regles’ 23 5.3. Policy 25 5.3.1. EndoCataluña 25 iv 5.3.2. La CUP’s Motion 26 Chapter 6 Menstrual Education: lessons from the embodied experience 29 6.1. Divine Menstruation – A Natural Gynaecology Workshop 31 6.2. Somiarte 32 6.3. Erika Irusta and SOY1SOY4 34 Chapter 7 Sustainable menstruation: ecological awareness and responsible consumption 38 7.1. -

USA V. Bradley (Chelsea) Manning: Army Court of Appeals Affirms Prior

UNITED STATES ARMY COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS Before CAMPANELLA, CELTNIEKS, and HAGLER Appellate Military Judges UNITED STATES, Appellee v. Private First Class BRADLEY E. MANNING (nka CHELSEA E. MANNING) United States Army, Appellant ARMY 20130739 U.S. Army Military District of Washington Denise R. Lind, Military Judge Colonel Corey J. Bradley, Staff Judge Advocate (pretrial) Colonel James R. Agar, II, Staff Judge Advocate (post-trial) For Appellant: Vincent J. Ward, Esquire (argued); Captain J. David Hammond, JA; Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan F. Potter, JA; Vincent J. Ward, Esquire; Nancy Hollander, Esquire (on brief); Lieutenant Colonel Christopher D. Carrier, JA. Amicus Curiae: For Electronic Frontier Foundation, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and the Center for Democracy and Technology: Jamie Williams, Esquire; Andrew Crocker, Esquire (on brief). For Amnesty International Limited: John K. Keker, Esquire; Dan Jackson, Esquire; Nicholas S. Goldberg, Esquire (on brief). For American Civil Liberties Union Foundation: Esha Bhandari, Esquire; Dror Ladin, Esquire; Ben Wizner, Esquire (on brief). For Open Society Justice Initiative: James Goldston, Esquire; Sandra Coliver, Esquire (on brief). For Appellee: Captain Catherine M. Parnell, JA (argued); Colonel Mark H. Sydenham, JA; Lieutenant Colonel A.G. Courie III, JA; Major Steve T. Nam, JA; Captain Timothy C. Donahue, JA; Captain Jennifer A. Donahue, JA; Captain Samuel E. Landes, JA (on brief); Captain Allison L. Rowley, JA. 31 May 2018 --------------------------------- OPINION OF THE COURT --------------------------------- MANNING—ARMY 20130739 CAMPANELLA, Senior Judge: A military judge sitting as a general court-martial convicted appellant, in accordance with her pleas, of one specification of violating a lawful general regulation and two specifications of general disorders in violation of Articles 92 and 134, Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), 10 U.S.C. -

2021 Fall Catalogue

PLAYWRIGHTS CANADA PRESS fall 2021 COVER ART BY MYRIAM WARES MYRIAMWARES.COM ORDERING AND DISTRIBUTION IN CANADA SALES Canadian Manda Group 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 t: 416.516.0911 | f: 416.516.0917 | e: [email protected] | w: www.mandagroup.com customer service & orders t: 1.855.626.3222 | f: 1.888.563.8327 | e: [email protected] Ellen Warwick, National Account Manager, Special Markets :: t: 416.516.0911 x240 Chris Hickey, Sales Director, Partner t: 416.516.0911 x229 Ryan Muscat, Account Manager, Ontario & Manitoba t: 416.516.0911 x243 Tim Gain, National Account Manager, Library Market t: 416.516.0911 x231 Iolanda Millar, Account Manager, British Columbia, Yukon & Northern Territories :: t: 604.662.3511 x246 Dave Nadalin, National Account Manager, Toronto t: 416.516.0911 x400 Nikki Turner, Account Manager, Toronto, Eastern Ontario & Special Markets :: t: 416.516.0911 x225 Jean Cichon, Account Manager, Alberta, Saskatchewan & Manitoba :: t: 403.202.0922 x245 Anthony Iantorno, Director, Online & Digital Sales :: t: 416.516.0911 x242 Kristina Koski, Account Manager, Special Markets t: 416.516.0911 x234 Joanne Adams, National Account Manager, Mass Market :: t: 416.516.0911 x224 David Farag, Account Manager, Toronto, Central & Northern Ontario Jacques Filippi, Account Manager, Quebec & Atlantic t: 416.516.0911 x248 Provinces :: t: 1.855.626.3222 x244 Emily Patry, Director, Marketing & Communications Kate Condon-Moriarty, Account Manager, British t: 416.516.0911 x230 Columbia :: t: 604.662.3511 x247 DISTRIBUTION University of Toronto Press Inc. 5201 Dufferin Street, Toronto, ON M3H 5T8 t: 1.800.565.9523 or 416.667.7791 | f: 1.800.221.9985 or 416.667.7832 | e: [email protected] To order by EDI: Through Pubnet: SAN 115 1134 All orders from individuals must be prepaid. -

Kirkus Reviews

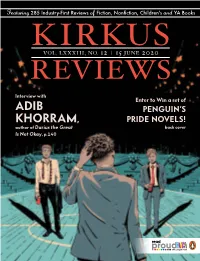

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

U.S. Charges Hacker with Illegally Accessing New York Times Computer Network

September 9, 2003 U.S. Department of Justice United States Attorney Southern District of New York James B. Comey Contact: Marvin, Smilon, Herbert Hadad, Michael Kulstad Public Information Office (212) 637-2600 Mark F. Mendelsohn (212) 637-2487 FBI Joseph A. Valiquette James, Margolin (212) 384-2715, 2720 U.S. Charges Hacker with Illegally Accessing New York Times Computer Network JAMES B. COMEY, United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and PASQUALE D’AMURO, the Assistant Director in Charge of the New York Office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, announced that ADRIAN LAMO was charged in Manhattan federal court with hacking into the internal computer network of the New York Times. LAMO surrendered today to federal authorities in Sacramento, California. According to a two-count criminal Complaint unsealed today in Manhattan federal court, on February 26, 2002, LAMO hacked into the New York Times’ internal computer network and accessed a database containing personal information (including home telephone numbers and Social Security numbers) for over 3,000 contributors to the New York Times’ Op-Ed page. As described in the Complaint, soon after being notified of the computer intrusion, the New York Times conducted an internal investigation and confirmed that an intruder had in fact hacked into its network and accessed the personal information for contributors to the Op-Ed page. In addition, according to the Complaint, the Times determined that the intruder had added an entry to that database for “Adrian Lamo,” listing personal information including LAMO’s cellular telephone number (415) 505-HACK, and a description of his areas of expertise as “computer hacking, national security, communications intelligence.” The Complaint states that the New York Times later learned that while inside its internal network, LAMO had set up five fictitious user identification names and passwords (“userids/passwords”) under the New York Times’ account with LexisNexis, an online subscription service that provides legal, news and other information for a fee. -

Ethical Hacking

Ethical Hacking Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press ETHICAL HACKING ETHICAL HACKING Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press 2019 The University of Ottawa Press (UOP) is proud to be the oldest of the francophone university presses in Canada and the only bilingual university publisher in North America. Since 1936, UOP has been “enriching intellectual and cultural discourse” by producing peer-reviewed and award-winning books in the humanities and social sciences, in French or in English. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Ethical hacking / Alana Maurushat. Names: Maurushat, Alana, author. Description: Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190087447 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019008748X | ISBN 9780776627915 (softcover) | ISBN 9780776627922 (PDF) | ISBN 9780776627939 (EPUB) | ISBN 9780776627946 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Hacking—Moral and ethical aspects—Case studies. | LCGFT: Case studies. Classification: LCC HV6773 .M38 2019 | DDC 364.16/8—dc23 Legal Deposit: First Quarter 2019 Library and Archives Canada © Alana Maurushat, 2019, under Creative Commons License Attribution— NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Printed and bound in Canada by Gauvin Press Copy editing Robbie McCaw Proofreading Robert Ferguson Typesetting CS Cover design Édiscript enr. and Elizabeth Schwaiger Cover image Fragmented Memory by Phillip David Stearns, n.d., Personal Data, Software, Jacquard Woven Cotton. Image © Phillip David Stearns, reproduced with kind permission from the artist. The University of Ottawa Press gratefully acknowledges the support extended to its publishing list by Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund, by the Canada Council for the Arts, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, and by the University of Ottawa. -

Liste Alphabétique Des DVD Du Club Vidéo De La Bibliothèque

Liste alphabétique des DVD du club vidéo de la bibliothèque Merci à nos donateurs : Fonds de développement du collège Édouard-Montpetit (FDCEM) Librairie coopérative Édouard-Montpetit Formation continue – ÉNA Conseil de vie étudiante (CVE) – ÉNA septembre 2013 A 791.4372F251sd 2 fast 2 furious / directed by John Singleton A 791.4372 D487pd 2 Frogs dans l'Ouest [enregistrement vidéo] = 2 Frogs in the West / réalisation, Dany Papineau. A 791.4372 T845hd Les 3 p'tits cochons [enregistrement vidéo] = The 3 little pigs / réalisation, Patrick Huard . A 791.4372 F216asd Les 4 fantastiques et le surfer d'argent [enregistrement vidéo] = Fantastic 4. Rise of the silver surfer / réalisation, Tim Story. A 791.4372 Z587fd 007 Quantum [enregistrement vidéo] = Quantum of solace / réalisation, Marc Forster. A 791.4372 H911od 8 femmes [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, François Ozon. A 791.4372E34hd 8 Mile / directed by Curtis Hanson A 791.4372N714nd 9/11 / directed by James Hanlon, Gédéon Naudet, Jules Naudet A 791.4372 D619pd 10 1/2 [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Daniel Grou (Podz). A 791.4372O59bd 11'09''01-September 11 / produit par Alain Brigand A 791.4372T447wd 13 going on 30 / directed by Gary Winick A 791.4372 Q7fd 15 février 1839 [enregistrement vidéo] / scénario et réalisation, Pierre Falardeau. A 791.4372 S625dd 16 rues [enregistrement vidéo] = 16 blocks / réalisation, Richard Donner. A 791.4372D619sd 18 ans après / scénario et réalisation, Coline Serreau A 791.4372V784ed 20 h 17, rue Darling / scénario et réalisation, Bernard Émond A 791.4372T971gad 21 grams / directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu ©Cégep Édouard-Montpetit – Bibliothèque de l’École nationale d'aérotechnique - Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2013 Page 1 A 791.4372 T971Ld 21 Jump Street [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. -

Who Watches the Watchmen? the Conflict Between National Security and Freedom of the Press

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment.