Climate Change Adaptation Manual Second Edition 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Developing Methods for the Field Survey and Monitoring of Breeding Short-Eared Owls (Asio Flammeus) in the UK: Final Report from Pilot Fieldwork in 2006 and 2007

BTO Research Report No. 496 Developing methods for the field survey and monitoring of breeding Short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) in the UK: Final report from pilot fieldwork in 2006 and 2007 A report to Scottish Natural Heritage Ref: 14652 Authors John Calladine, Graeme Garner and Chris Wernham February 2008 BTO Scotland School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA Registered Charity No. SC039193 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF APPENDICES...........................................................................................................vi SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... viii CRYNODEB............................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................xvi 1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS...........................................................................................2 -

The Phylogenetic Relationships and Generic Limits of Finches

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62 (2012) 581–596 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev The phylogenetic relationships and generic limits of finches (Fringillidae) ⇑ Dario Zuccon a, , Robert Pryˆs-Jones b, Pamela C. Rasmussen c, Per G.P. Ericson d a Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Bird Group, Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, Akeman St., Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK c Department of Zoology and MSU Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA d Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships among the true finches (Fringillidae) have been confounded by the recurrence Received 30 June 2011 of similar plumage patterns and use of similar feeding niches. Using a dense taxon sampling and a com- Revised 27 September 2011 bination of nuclear and mitochondrial sequences we reconstructed a well resolved and strongly sup- Accepted 3 October 2011 ported phylogenetic hypothesis for this family. We identified three well supported, subfamily level Available online 17 October 2011 clades: the Holoarctic genus Fringilla (subfamly Fringillinae), the Neotropical Euphonia and Chlorophonia (subfamily Euphoniinae), and the more widespread subfamily Carduelinae for the remaining taxa. Keywords: Although usually separated in a different -

Assessing Population Changes from Disparate Data Sources: the Decline of the Twite Carduelis Flavirostris in England

Bird Conservation International (2009) 19:401–416. ª BirdLife International, 2009 doi:10.1017/S0959270909990086 Assessing population changes from disparate data sources: the decline of the Twite Carduelis flavirostris in England ANDRE´ F. RAINE, ANDREW F. BROWN, TATSUYA AMANO and WILLIAM J. SUTHERLAND Summary Conservationists often find it difficult to assess long-term population change in a species when the only data available are from disparate sources. This is especially the case when a range of survey methodologies and reporting units have been utilised and the results have been published in the ‘grey’ literature. Although the production of a cohesive assessment of change may be a daunting task, in such circumstances, a sound assessment of change is often possible. We illustrate this by considering the decline of the Twite Carduelis flavirostris in England. Whilst there is evidence of decline, it is widely dispersed and the losses have yet to be formally documented. To assess longer-term change, we reviewed information available in county avi- faunas and historical accounts of the status of the species throughout its former English range. Twite now only breed regularly in six of their 12 historical range counties, and in all of these six, the birds have declined markedly in abundance. We collated and analysed data drawn from a diverse range of surveys and county bird reports to assess more recent change and assessed contemporary distribution and abundance during our own surveys of breeding colonies in the South Pennines, an area supporting the last known nesting colonies in England. Combined, the data clearly indicate that the range and numbers of breeding Twite have declined considerably since the 1970s. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

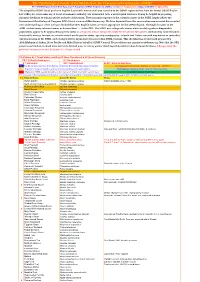

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

410 Conservation News

410 Conservation news methods described in these documents are designed to Concerns about trade in wild finches in Algeria enable NGO facilitators to use both livelihood and conser- vation criteria to select the most appropriate market sectors Songbird species across the globe suffer from excessive col- on which to focus. Guidance is provided on how to engage lection for trade. This trade can operate outside regulation key market actors, including private sector actors that con- and can lead to significant declines in wild populations. servationists may not traditionally interact with and who Songbirds such as finches are popular pets because of may not initially be interested in the environmental impacts their singing ability, cultural value, and in some cases the so- of their businesses. Tips are provided on how to frame cial status that owning them can offer. The European gold- discussions in terms of business interests, such as product finch Carduelis carduelis, serin Serinus serinus and common quality and sustainability of supply, and how these are linnet Linaria cannabina range across Europe, North Africa, related to sustainable use and conservation. Exercises the Middle East and East Asia and, although they are cate- are provided to help empower marginalized producers to gorized as Least Concern by IUCN, they are affected by a have the skills and confidence to negotiate with input range of factors that influence their conservation. The wild and service providers, as well as with traders, and with populations of serins and linnets are decreasing and, al- government agencies whose policies influence the business though the European goldfinch is increasing in numbers enabling environment. -

Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Wildlife Guide

Wildlife Guide Welcome to the Moors for the Future Partnership’s guide to the birds, mammals, insects and reptiles of the moorlands of the Peak District National Park and South Pennines. Use this guide to try your hand at spotting and identifying some of the many beautiful and fascinating animals that help to make these moorlands such important and unique places. If you have a smartphone search for MoorWILD on the Apple and Android app stores to find our interactive version of this field guide. Birds Buzzard Buteo buteo - A medium sized bird of prey (length 48-56cm, wing span 110 - 130cm) with broad wings with obvious “fingers”. - Soars frequently and commonly seen sitting on fence posts and telegraph poles. - Eats a wide variety of prey; mostly voles, also rabbits, reptiles, amphibians, insects and birds. Can often be seen in fields eating earthworms. - Sexes are alike. - Voice - very vocal, often a plaintive mewing “piiiyay” call, especially in flight. - The work carried out by the Moors for the Future Partnership on the MoorLIFE project has helped to restore and preserve the moorland habitats they use to hunt throughout the year, including the breeding season. Curlew Numenius arquata - Large (length 48-57cm (incl. bill), wing span 89-106cm), elegant brown wader with a long (9-15cm) strongly decurved beak. - Sexes are alike. - Voice - a beautiful bubbling call in flight. Also onomatopoeic “coorrliii” call. - The work carried out by the Moors for the Future Partnership on the MoorLIFE project has helped to restore and preserve their summer breeding habitats. Birds Dunlin Calidris alpina - A small, starling-sized wader (length 17-21cm, wing span 32-36cm) with a rather short, slightly decurved bill. -

Dumfries & Galloway

12 Wildlife Walks Dumfries & Galloway visitdumfriesandgalloway.co.uk Welcome Contents 02 A walk on the wild side 05 VisitScotland Information Centres Scottish Outdoor Access Code 06 The Wig 08 Mull of Galloway 10 The Burnside Trail 12 Cairnsmore of Fleet 12 14 Ken-Dee Marshes 16 Mersehead 11 18 Kirkconnel Flow 20 The Reedbed Ramble 22 Castle Loch 24 Langholm Moorland 26 Moffat 10 28 Baker’s Burn Path 9 5 7 1 4 8 3 Cover Images Front – red squirrel 6 Back – bluebells at Castramon wood Credits Photography: Lorne Gill/SNH, Laurie Campbell/SNH, Glyn Slattery/SNH, George Logan/SNH, John Wright, Cat Barlow, SNH, Mark Pollitt DGERC Design www.stand-united.co.uk www.weesleekit.co.uk 2 VisitScotland has published this guide in good faith to reflect information submitted to it by Scottish Natural Heritage. Although VisitScotland has taken reasonable steps to confirm the information contained in the guide at the time of going to press, it cannot guarantee that the information published is and remains accurate. VisitScotland 1 The Wig 5 Ken-Dee Marshes 9 Castle Loch accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation contained in the guide and excludes all liability for loss or damage caused by any reliance placed on the 2 Mull of Galloway 6 Mersehead 10 Langholm Moorland information contained in the guide. 3 The Burnside Trail 7 Kirkconnel Flow 11 Moffat 4 Cairnsmore of Fleet 8 The Reedbed Ramble 12 Baker’s Burn Path For information and to book accommodation go to visitscotland.com To find out more about Dumfries & Galloway go to visitdumfriesandgalloway.co.uk 01 A walk on the wild side… Dumfries & Galloway is the perfect place to see amazing wildlife in unspoiled, natural habitats and whatever time of year you choose to visit there is always something new and exciting to witness. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Scope and Scale of Illegal Killing and Taking of Wild Birds in the Arabian Peninsula, Iran and Iraq

A preliminary assessment of the scope and scale of illegal killing and taking of wild birds in the Arabian peninsula, Iran and Iraq ANNE-LAURE BROCHET, SHARIF JBOUR, ROBERT D SHELDON, RICHARD PORTER, VICTORIA R JONES, WAHEED AL FAZARI, OMAR AL SAGHIER, SAEED ALKHUZAI, LAITH ALI AL-OBEIDI, RICHARD ANGWIN, KORSH ARARAT, MIKE POPE, MOHAMMED Y SHOBRAK, MAÏA S WILLSON, SADEGH SADEGHI ZADEGAN & STUART H M BUTCHART Summary: High levels of illegal killing and taking of wild birds were recently reported for eastern Mediterranean countries, and anecdotal information from other countries of the Middle East suggests this may be a significant conservation issue for the whole region. We quantified the approximate scale and scope of this threat in the Arabian peninsula, Iran and Iraq, using a diverse range of data sources and incorporating expert knowledge. We estimate that at least 1.7–4.6 million (best esti- mate: 3.2 million) birds of at least 413 species may be killed or taken illegally each year in this region, many of them on migration. This is likely to be an underestimate as data were unavailable for parts of the region. The highest estimated country total, of 1.7 million birds, was for Saudi Arabia despite data being available only for the northern part of the country. Several species of global conservation concern were illegally killed or taken, including Marbled Teal Marmaronetta angustirostris, Common Pochard Aythya ferina and European Turtle-dove Streptopelia turtur (all classified by BirdLife International as Vulnerable on the global IUCN Red List). Of greater concern, Sociable Lapwing Vanellus gregarius (Critically Endangered) was also reported to be known or likely to be killed illegally each year in high numbers relative to its small population size. -

The Twite (Linaria Flavirostris) Is a Small Brown Passerine Bird in the Finch Family Fringillidae

Twite The Twite (Linaria flavirostris) is a small brown passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. It is similar in size and shape to a Linnet, at 13 to 13.5 centimetres (5.1 to 5.3 in) long. It lacks the red head patch and breast shown by the Linnet and the Redpolls. It is brown streaked with black above and a pink rump. The underparts are buff to whitish, streaked with brown. The conical bill is yellow in winter and grey in summer. The call is a distinctive twit, from which its name derives and the song contains fast trills and twitters. Twites can form large flocks outside the breeding season, sometimes mixed with other finches on coasts and salt marshes. They feed mainly on seeds. The Twite breeds in northern Europe and across central Asia. Treeless moorland is favoured for breeding. It builds its nest in a bush, laying 5–6 light blue eggs. It is partially resident, but many birds migrate further south, or move to the coasts. It has declined sharply in parts of its range, notably Ireland. In the UK, the Twite is the subject of several research projects in the Pennines, the Scottish Highlands and the North Wales and Lancashire coastlines. Records show that the birds to the east of the Pennine hills move to the Southeast coast in winter and those to the west winter between Lancashire and the Hebrides. The Welsh population winters almost exclusively in Flintshire. In 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus included the Twite in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Fringilla flavirostris. -

Diversity and Endemism in Tidal-Marsh Vertebrates

Studies in Avian Biology No. 32:32-53 DIVERSITY AND ENDEMISM IN TIDAL-MARSH VERTEBRATES RUSSELL GREENBERG AND JESúS E. MALDONADO Abstract. Tidal marshes are distributed patcliily, predominantly along the mid- to high-latitude coasts of the major continents. The greatest extensions of non-arctic tidal marshes are found along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America, but local concentrations can be found in Great Britain, northern Europe, northern Japan, northern China, and northern Korea, Argentina-Uruguay-Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand. We tallied the number of terrestrial vertebrate species that regularly occupy tidal marshes in each of these regions, as well as species or subspecies that are largely restricted to tidal marshes. In each of the major coastal areas we found 8-21 species of breeding birds and 13-25 species of terrestrial mammals. The diversity of tidal-marsh birds and mammals is highly inter-correlated, as is the diversity of species restricted to saltmarshes. These values are, in turn, correlated with tidal-marsh area along a coastline. We estimate approximately seven species of turtles occur in brackish or saltmarshes worldwide, but only one species is endemic and it is found in eastern North America. A large number of frogs and snakes occur opportunistically in tidal marshes, primarily in southeastern United States, particularly Florida. Three endemic snake taxa are restricted to tidal marshes of eastern North America as well. Overall, only in North America were we able to find documentation for multiple taxa of terrestrial vertebrates associated with tidal marshes. These include one species of mammal and two species of birds, one species of snake, and one species of turtle.