Assessing Population Changes from Disparate Data Sources: the Decline of the Twite Carduelis Flavirostris in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Developing Methods for the Field Survey and Monitoring of Breeding Short-Eared Owls (Asio Flammeus) in the UK: Final Report from Pilot Fieldwork in 2006 and 2007

BTO Research Report No. 496 Developing methods for the field survey and monitoring of breeding Short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) in the UK: Final report from pilot fieldwork in 2006 and 2007 A report to Scottish Natural Heritage Ref: 14652 Authors John Calladine, Graeme Garner and Chris Wernham February 2008 BTO Scotland School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA Registered Charity No. SC039193 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF APPENDICES...........................................................................................................vi SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... viii CRYNODEB............................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................xvi 1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS...........................................................................................2 -

Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Wildlife Guide

Wildlife Guide Welcome to the Moors for the Future Partnership’s guide to the birds, mammals, insects and reptiles of the moorlands of the Peak District National Park and South Pennines. Use this guide to try your hand at spotting and identifying some of the many beautiful and fascinating animals that help to make these moorlands such important and unique places. If you have a smartphone search for MoorWILD on the Apple and Android app stores to find our interactive version of this field guide. Birds Buzzard Buteo buteo - A medium sized bird of prey (length 48-56cm, wing span 110 - 130cm) with broad wings with obvious “fingers”. - Soars frequently and commonly seen sitting on fence posts and telegraph poles. - Eats a wide variety of prey; mostly voles, also rabbits, reptiles, amphibians, insects and birds. Can often be seen in fields eating earthworms. - Sexes are alike. - Voice - very vocal, often a plaintive mewing “piiiyay” call, especially in flight. - The work carried out by the Moors for the Future Partnership on the MoorLIFE project has helped to restore and preserve the moorland habitats they use to hunt throughout the year, including the breeding season. Curlew Numenius arquata - Large (length 48-57cm (incl. bill), wing span 89-106cm), elegant brown wader with a long (9-15cm) strongly decurved beak. - Sexes are alike. - Voice - a beautiful bubbling call in flight. Also onomatopoeic “coorrliii” call. - The work carried out by the Moors for the Future Partnership on the MoorLIFE project has helped to restore and preserve their summer breeding habitats. Birds Dunlin Calidris alpina - A small, starling-sized wader (length 17-21cm, wing span 32-36cm) with a rather short, slightly decurved bill. -

Dumfries & Galloway

12 Wildlife Walks Dumfries & Galloway visitdumfriesandgalloway.co.uk Welcome Contents 02 A walk on the wild side 05 VisitScotland Information Centres Scottish Outdoor Access Code 06 The Wig 08 Mull of Galloway 10 The Burnside Trail 12 Cairnsmore of Fleet 12 14 Ken-Dee Marshes 16 Mersehead 11 18 Kirkconnel Flow 20 The Reedbed Ramble 22 Castle Loch 24 Langholm Moorland 26 Moffat 10 28 Baker’s Burn Path 9 5 7 1 4 8 3 Cover Images Front – red squirrel 6 Back – bluebells at Castramon wood Credits Photography: Lorne Gill/SNH, Laurie Campbell/SNH, Glyn Slattery/SNH, George Logan/SNH, John Wright, Cat Barlow, SNH, Mark Pollitt DGERC Design www.stand-united.co.uk www.weesleekit.co.uk 2 VisitScotland has published this guide in good faith to reflect information submitted to it by Scottish Natural Heritage. Although VisitScotland has taken reasonable steps to confirm the information contained in the guide at the time of going to press, it cannot guarantee that the information published is and remains accurate. VisitScotland 1 The Wig 5 Ken-Dee Marshes 9 Castle Loch accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation contained in the guide and excludes all liability for loss or damage caused by any reliance placed on the 2 Mull of Galloway 6 Mersehead 10 Langholm Moorland information contained in the guide. 3 The Burnside Trail 7 Kirkconnel Flow 11 Moffat 4 Cairnsmore of Fleet 8 The Reedbed Ramble 12 Baker’s Burn Path For information and to book accommodation go to visitscotland.com To find out more about Dumfries & Galloway go to visitdumfriesandgalloway.co.uk 01 A walk on the wild side… Dumfries & Galloway is the perfect place to see amazing wildlife in unspoiled, natural habitats and whatever time of year you choose to visit there is always something new and exciting to witness. -

The Twite (Linaria Flavirostris) Is a Small Brown Passerine Bird in the Finch Family Fringillidae

Twite The Twite (Linaria flavirostris) is a small brown passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. It is similar in size and shape to a Linnet, at 13 to 13.5 centimetres (5.1 to 5.3 in) long. It lacks the red head patch and breast shown by the Linnet and the Redpolls. It is brown streaked with black above and a pink rump. The underparts are buff to whitish, streaked with brown. The conical bill is yellow in winter and grey in summer. The call is a distinctive twit, from which its name derives and the song contains fast trills and twitters. Twites can form large flocks outside the breeding season, sometimes mixed with other finches on coasts and salt marshes. They feed mainly on seeds. The Twite breeds in northern Europe and across central Asia. Treeless moorland is favoured for breeding. It builds its nest in a bush, laying 5–6 light blue eggs. It is partially resident, but many birds migrate further south, or move to the coasts. It has declined sharply in parts of its range, notably Ireland. In the UK, the Twite is the subject of several research projects in the Pennines, the Scottish Highlands and the North Wales and Lancashire coastlines. Records show that the birds to the east of the Pennine hills move to the Southeast coast in winter and those to the west winter between Lancashire and the Hebrides. The Welsh population winters almost exclusively in Flintshire. In 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus included the Twite in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Fringilla flavirostris. -

Diversity and Endemism in Tidal-Marsh Vertebrates

Studies in Avian Biology No. 32:32-53 DIVERSITY AND ENDEMISM IN TIDAL-MARSH VERTEBRATES RUSSELL GREENBERG AND JESúS E. MALDONADO Abstract. Tidal marshes are distributed patcliily, predominantly along the mid- to high-latitude coasts of the major continents. The greatest extensions of non-arctic tidal marshes are found along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America, but local concentrations can be found in Great Britain, northern Europe, northern Japan, northern China, and northern Korea, Argentina-Uruguay-Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand. We tallied the number of terrestrial vertebrate species that regularly occupy tidal marshes in each of these regions, as well as species or subspecies that are largely restricted to tidal marshes. In each of the major coastal areas we found 8-21 species of breeding birds and 13-25 species of terrestrial mammals. The diversity of tidal-marsh birds and mammals is highly inter-correlated, as is the diversity of species restricted to saltmarshes. These values are, in turn, correlated with tidal-marsh area along a coastline. We estimate approximately seven species of turtles occur in brackish or saltmarshes worldwide, but only one species is endemic and it is found in eastern North America. A large number of frogs and snakes occur opportunistically in tidal marshes, primarily in southeastern United States, particularly Florida. Three endemic snake taxa are restricted to tidal marshes of eastern North America as well. Overall, only in North America were we able to find documentation for multiple taxa of terrestrial vertebrates associated with tidal marshes. These include one species of mammal and two species of birds, one species of snake, and one species of turtle. -

SCOTTISH Birds Offered Tremendous Views As They Fed on the Happened

*SB 30(1) COV 17/2/10 17:45 Page 1 least. The power of the waves was moving even a PhotoSP T man of my girth, but I was getting the shots I Plate 88. Late October© 2008 saw an unprece- wanted of birds lifting up and then settling back dented arrival of Grey Phalaropes to Shetland. The down on the sea. Magic stuff - until the inevitable SCOTTISH birds offered tremendous views as they fed on the happened. A ‘roller’ that I knew was going to be at sea. To get something better than a run-of-the-mill least shoulder-height was heading my way, so I bird-on-water shot, I was keen to capture them in turned to face it with a degree of apprehension. flight as they lifted up for their short flights. Camera and lens held well above my head, the wave rolled ‘through’ me at breast level and BIRDS After a day of ‘beach-bound’ shooting I noticed that freezing cold water started pouring into my chest most of my flight shots were at least sharp, but the waders. Walking just 10 or so metres with heaven lobed feet - one of the most important features I knows how many litres of icy water inside them was Volume 30 (1) 30 (1) Volume wanted to capture - were obscured by either the a nightmare and I clambered up the beach back to wings or the body of the bird. This was because I my van like one of Shackleton’s crew landing on had been photographing on a sloping pebble Elephant Island! The result? Well, I’m still picking bits beach and was ‘above’ the birds. -

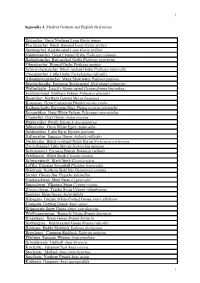

Appendix 4. Modern German and English Bird Names

1 Appendix 4. Modern German and English bird names. Eistaucher Great Northern Loon Gavia immer Prachttaucher Black-throated Loon Gavia arctica Sterntaucher Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Haubentaucher Great Crested Grebe Podiceps cristatus Rothalstaucher Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Ohrentaucher Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus Schwarzhalstaucher Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Zwergtaucher Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis Atlantiksturmtaucher Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Sturmschwalbe European Storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus Wellenläufer Leach’s Storm-petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa Eissturmvogel Northern Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis Basstölpel Northern Gannet Morus bassanus Kormoran Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Krähenscharbe European Shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis Rosapelikan Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus Graureiher Grey Heron Ardea cinerea Purpurreiher Purple Heron Ardea purpurea Silberreiher Great White Egret Ardea alba Seidenreiher Little Egret Egretta garzetta Rallenreiher Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides Nachtreiher Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Zwergdommel Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus Rohrdommel Eurasian Bittern Botaurus stellaris Weißstorch White Stork Ciconia ciconia Schwarzstorch Black Stork Ciconia nigra Löffler Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia Waldrapp Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita Sichler Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus Höckerschwan Mute Swan Cygnus olor Singschwan Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus Zwergschwan Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus Saatgans Bean -

BIRD NEWS Vol. 29 No. 4 Winter 2018

BIRD NEWS Vol. 29 No. 4 Winter 2018 Club news and announcements New to CBC Council – Mike and Lyn Mills Black-tailed Godwits - the French connection Swift survey 2018 - preliminary results The Long-eared Owl (Asio otus) in Cumbria Recent reports Contents - see back page Twinned with Cumberland Bird Observers Club New South Wales, Australia http://www.cboc.org.au If you want to borrow CBOC publications please contact the Secretary who holds some. Officers of the Society Council Chairman: Malcolm Priestley, Havera Bank, Howgill Lane, Sedbergh, LA10 5HB tel. 015396 20104; [email protected] Vice-chairmen: Mike Carrier, Peter Howard, Nick Franklin Secretary: David Piercy, 64 The Headlands, Keswick, CA12 5EJ; tel. 017687 73201; [email protected] Treasurer: Treasurer: David Cooke, Mill Craggs, Bampton, CA10 2RQ tel. 01931 713392; [email protected] Field trips organiser: Vacant Talks organiser: Vacant Members: Colin Auld Jake Manson Lyn Mills Mike Mills Adam Moan Recorders County: Chris Hind, 2 Old School House, Hallbankgate, Brampton, CA8 2NW [email protected] tel. 016977 46379 Barrow/South Lakeland: Ronnie Irving, 24 Birchwood Close, Kendal LA9 5BJ [email protected] tel. 01539 727523 Carlisle & Eden: Chris Hind, 2 Old School House, Hallbankgate, Brampton, CA8 2NW [email protected] tel. 016977 46379 Allerdale & Copeland: Nick Franklin, 19 Eden Street, Carlisle CA3 9LS [email protected] tel. 01228 810413 C.B.C. Bird News Editor: Dave Piercy B.T.O. Representatives Cumbria: Colin Gay, 8 Victoria Street, Millom LA18 5AS [email protected] tel. 01229 773820 Assistant rep: Dave Piercy 94 Club news and announcements AGM report At the AGM of October 5th 2018 Mike and Lyn Mills were elected as mem- bers of council. -

Management Prescriptions for Twite in Ireland

Management prescriptions for twite in Ireland Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 52 Management prescriptions for twite in Ireland Derek T. McLoughlin Citation: McLoughlin, D.T. (2011) Management prescriptions for twite in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manual s, No. 52. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Keywords: twite, prescription, habitat management, agri-environment schemes, Carduelis flavirostris Cover photo: Twite during winter season © Liam McDevitt The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: David Norriss; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: F. Marnell & N. Kingston © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2011 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Species management plan for twite ____________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................1 DOCUMENT MAP ..............................................................................................................................................2 1.0 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................................... -

Arctic Biodiversity Assessment

142 Arctic Biodiversity Assessment Incubating red knot Calidris canutus after a snowfall at Cape Sterlegova, Taimyr, Siberia, 27 June 1991. This shorebird represents the most numerically dominating and species rich group of birds on the tundra and the harsh conditions that these hardy birds experience in the high Arctic. Photo: Jan van de Kam. 143 Chapter 4 Birds Lead Authors Barbara Ganter and Anthony J. Gaston Contributing Authors Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Peter Blancher, David Boertmann, Brian Collins, Violet Ford, Arnþór Garðasson, Gilles Gauthier, Maria V. Gavrilo, Grant Gilchrist, Robert E. Gill, David Irons, Elena G. Lappo, Mark Mallory, Flemming Merkel, Guy Morrison, Tero Mustonen, Aevar Petersen, Humphrey P. Sitters, Paul Smith, Hallvard Strøm, Evgeny E. Syroechkovskiy and Pavel S. Tomkovich Contents Summary ..............................................................144 4.5. Seabirds: loons, petrels, cormorants, jaegers/skuas, gulls, terns and auks .....................................................160 4.1. Introduction .......................................................144 4.5.1. Species richness and distribution ............................160 4.2. Status of knowledge ..............................................144 4.5.1.1. Status ...............................................160 4.2.1. Sources and regions .........................................144 4.5.1.2. Endemicity ..........................................161 4.2.2. Biogeography ..............................................147 4.5.1.3. Trends ..............................................161