''Combat Charities'': New Phenomenon of the 21St Century Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point and Shoot Education Screening Dear Teachers

Point and Shoot Education Screening Dear Teachers, Welcome to the Milwaukee Film Education Screenings! We are delighted to have you and thankful that so many Milwaukee-area teachers are interested in incorporating film into the classroom! So that we may continue providing these opportunities, we do require that your class complete at least one activity in conjunction with the screening of Point and Shoot. Your cooperation ensures that we are able to continue applying for funding to bring in these films and offer them to you (and literally thousands of students) at such a low cost. This packet includes several suggestions of activities and discussion questions that fulfill a variety of Common Core Standards. Let me know if you need a different file format! Feel free to adapt and modify the activities for your own classroom. Students could also simply journal, blog, or write about their experience. New this year we are introducing an Essay Contest to this packet! Submit writing from your students in response to the standard prompt we offer here by November 3, 2014 for consideration. A panel of judges will select the best essay and a runner-up in each grade range to receive a bookstore gift certificate as a prize. See the Essay Contest handout in this packet for more details. You can send evidence of the work you did to integrate the film into your classroom electronically or by mail. This could include: links to online content, Google Drive folders, scanned material, photocopied or original student work concerning the film/film-going experience or even your own anecdotal, narrative accounts. -

Discussion Guide

POV Community Engagement & Education DISCUSSION GUIDE Point and Shoot A Film by Marshall Curry www.pbs.org/pov LETTER FROM THE FILMMAKER Three years ago, I got an email out of the blue from a young guy named Matt VanDyke. He introduced himself, said he had seen my films and told me he had recently returned from Libya, where he had been helping rebels overthrow dictator Muammar Gaddafi. He said he had over 100 hours of footage from the ex- perience and thought it would make a great documentary. I was intrigued, but explained that I only worked on projects where I had complete creative independence and control, and he said he understood. A few weeks later he came to New York and spent an afternoon telling his story to my producing partner, Elizabeth Martin (who is also my wife), and me. Matt was a fascinating person, provocative and hard to pin down. His story was rich with questions about how we become adults, about adventure and idealism and about the nature of war in the “age of the selfie.” After he left, my wife and I talked for hours about his story and the issues it had raised. Generating those kinds of discussions is the reason I make doc- umentaries. So we thought, “Let’s make a film that replicates the experience we just had, where the audience sits down with a stranger and hears an amazing, controversial story—and then walks out of the theater to grapple with it.” When I was younger I used to love hitchhiking because it brought me in touch with people whom I would otherwise never meet—people whose lives and world-views were completely dif- ferent from mine. -

Cyber Activities in the Syrian Conflict CSS CY

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT Hotspot Analysis The use of cybertools in an internationalized civil war context: Cyber activities in the Syrian conflict Zürich, October 2017 Version 1 Risk and Resilience Team Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich The use of cybertools in an internationalized civil war context: Cyber activities in the Syrian conflict Authors: Marie Baezner, Patrice Robin © 2017 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Contact: Center for Security Studies Haldeneggsteig 4 ETH Zürich CH-8092 Zürich Switzerland Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch Analysis prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich ETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Group; Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching; Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSS Disclaimer: The opinions presented in this study exclusively reflect the authors’ views. Please cite as: Baezner, Marie; Robin, Patrice (2017): Hotspot Analysis: The use of cybertools in an internationalized civil war context: Cyber activities in the Syrian conflict, October 2017, Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich. 2 The use of cybertools in an internationalized civil war context: Cyber activities in the Syrian conflict Table of Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Background and chronology 6 3 Description 9 3.1 Attribution and actors 9 Pro-government groups 9 Anti-government groups 11 Islamist groups 11 State actors 12 Non-aligned groups 13 3.2 Targets 13 3.3 Tools and techniques 14 Data breaches 14 -

No Concessions to Media As Indiscriminate Repression Continues in Countries with Pro-Democracy Protests 12 April 2011 BAHRAIN

Middle East & North Africa - Yemen Unending repression No concessions to media as indiscriminate repression continues in countries with pro-democracy protests 12 April 2011 BAHRAIN Reporters Without Borders strongly condemns netizen Zakariya Rashid Hassan’s death in detention on 9 April, six days after his arrest on charges of inciting hatred, disseminating false news, promoting sectarianism and calling for the regime’s overthrow in online forums. He moderated a now-closed forum providing information about his village of origin, Al-Dair. His family has rejected the interior ministry’s claim that he died as a result of sickle cell anemia complications. Three other netizens are still detained. They are Fadhel Abdulla Ali Al-Marzooq (arrested on 24 March), Ali Hasan Salman Al-Satrawi (arrested on 25 March) and Hani Muslim Mohamed Al-Taif (arrested on 27 March). Marzooq and Taif moderated forums in which Internet users could discuss the ongoing events. Satrawi was a forum member. There is no news of Abduljalil Al-Singace, a blogger arrested on 16 March. Reporters Without Borders is also worried that Nabeel Rajab, the head of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, has been accused by a military prosecutor of posting a “fabricated” photo of the injuries inflicted on Ali Isa Saqer, one of two people who died in detention on 9 April. Rajab posted the photo on Twitter the same day, saying Saqer had died as a result of mistreatment while in police custody. As previously noted, theInternational Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) reported that the military prosecutor general issued a decree on 28 March – Decision No.5 of 2011 – under which the publication of any information about ongoing investigations by military prosecutors is banned on national security grounds. -

A Micro-History of an In-Service Teacher Training Programme in Post-Revolutionary Libya

A micro-history of an in-service teacher training programme in post-Revolutionary Libya A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Benedict C.M. Gray School of Environment, Education and Development COPYRIGHT STATEMENT i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns certain copyright or related rights in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Manchester certain rights to use such Copyright, including for administrative purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts and whether in hard or electronic copy, may be made only in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended) and regulations issued under it or, where appropriate, in accordance with licensing agreements which the University has from time to time. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of certain Copyright, patents, designs, trademarks and other intellectual property (the “Intellectual Property”) and any reproductions of copyright works in the thesis, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property and/or Reproductions. iv. Further information on the conditions under which disclosure, publication and commercialisation of this thesis, the Copyright and any Intellectual Property and/or Reproductions described in it may take place is available in the University IP Policy (see http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/DocuInfo.aspx?DocID=24420), in any relevant Thesis restriction declarations deposited in the University Library, the University Library’s regulations (see http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/about/regulations/) and in the University’s policy on Presentation of Theses. -

John Paul II

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2014 JAMADA ALTHANI 26, 1435 AH No: 16147 Russia accused In Cairo, one Barcelona of seeking to family’s story ex-coach trigger ‘third shows rise of Vilanova world war’7 radical threat9 dies48 at 45 Drunk passenger Max 41º 150 Fils sparks hijack alert Min 21º Security forces storm airport; Australian detained DENPASAR: A drunk passenger sparked a hijack alert on a Virgin Australia flight heading for the Indonesian resort island of Bali yesterday when he attempted to break into the cockpit, officials said. Security forces rushed to the air- port when the Boeing 737-800 touched down on the pop- ular island, after the pilot reported the Brisbane to Bali flight had been hijacked, Indonesian authorities said. However, Virgin Australia said the drunken passenger had sparked a false alarm when he banged on the cockpit door. Indonesian police later arrested Matt Christopher Lockley, an Australian national. “This is no hijacking, this is a miscommunication,” said Heru Sudjatmiko, a Virgin Australia official in Bali. “What happened was there was a drunk person... too much alcohol consumption caused him to act aggressively.”“Based on the report I received, the passenger tried to enter the cockpit, through the cockpit door, by banging on the door.” He said the man was stopped by crew, handcuffed and placed in a seat at the back of the plane, which was carry- ing 137 passengers and seven crewmembers. After landing the passenger, who was unarmed, was taken off the air- craft and detained. Officials said he did not try to resist arrest. -

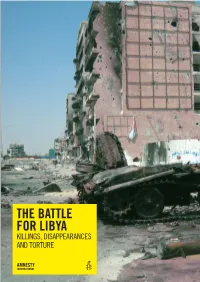

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4. -

Quest for Personal Transformation Takes Timid Biker 35,000 Miles to Libyan Revolution, Prison and Self-Recorded Stardom in POV’S ‘Point and Shoot,’ Monday, Aug

Contacts: POV Communications: 212-989-7425. [email protected] Cathy Fisher, [email protected]; Brian Geldin, [email protected] POV online pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom Quest for Personal Transformation Takes Timid Biker 35,000 Miles to Libyan Revolution, Prison and Self-Recorded Stardom in POV’s ‘Point and Shoot,’ Monday, Aug. 24 on PBS Documentary by Two-Time Oscar® Nominee Marshall Curry Illustrates the Camera’s Central Role in Documenting—and Shaping—Modern Identity and World Events A Co-production of Marshall Curry Productions, American Documentary | POV and ITVS “A gripping nonfiction thriller. Riveting . suspenseful . an extraordinary and quietly disturbing film.” —David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter Matt VanDyke was a recent grad with a love of video games and action movies when he decided to embark on a “crash course in manhood.” With a motorcycle and a video camera, he set off on a life- changing 35,000-mile odyssey across North Africa and the Middle East that led to his participation in the 2011 Libyan revolution against Muammar Gaddafi and six-month imprisonment in Libya. As VanDyke worked to reshape himself, he also helped create a stunning portrait of how the ever- present cameras in our “selfie society” not only record our lives, but also craft who we become. Two-time Oscar® nominee Marshall Curry, celebrating his 10th anniversary with POV, tells VanDyke’s amazing story in Point and Shoot, premiering Monday, AuG. 24 at 10 p.m. on PBS (check local listings). Winner of the Best Documentary Feature Award at the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival, Point and Shoot is Curry’s fourth film with POV; two of his previous POV films—Street Fight and If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front —were nominated for Academy Awards. -

Filmfest Thursday Saturday

30th Annual FilmFest Thursday Saturday Soldier on the Roof (3:00pm) Emergency Cinema (10:15am) ~Very short films about the situation in Syria. Courtesy of Ruth Diskin Films ~The world of settlers in Hebron. Cairo 678 (8:20pm) Friday They Were Promised the Sea (11:10am) Courtesy of Global Film Initiative ~Combating sexual harrassment in Egypt. Courtesy of BiCom Productions Sunday ~Identity issues of Moroccan Jews. Falafelism (9:00am) FILM HIGHLIGHTS The Virgin, the Copts and Me (2:05pm) Courtesy of AFD/Typecast Films ~Can food lead to peace? Courtesy of Icarus Films ~Tribulations of recreating a miracle. October 10-13, 2013 New Orleans, Louisiana Registration required Maurepas - 3rd Floor Wear your badge to enter FilmFest Film Schedule Thursday October 10 Saturday October 12 10:00am Mad Mad Mad World (the MESA FilmFest Logo) (4) 8:00am Bacha Posh: You Will Be a Boy, My Daughter (52) 10:05am Weapon of Choice (45) 8:55am Things I Heard on Wednesdays (9) 10:55am Palestine in the South (52) 9:05am MOMENTS (8) 11:55am Back Door Channels (102) 9:15am Camera/Woman (59) 1:40pm Jasad and the Queen of Contradictions (40) 2:25pm DINOSAUR (21) 10:15am Emergency Cinema (28) See page 15 for the list of films being screened. 2:50pm OBOUR (CROSSING) (7) vFeaturing introduction/Q&A with an associate of the 3:00pm Soldier on the Roof (80) Abounaddara Collective. 4:25pm Living in Limbo (12) 4:40pm Donor Opium (25) 11:00am Al-Muqanna’ (The Masked) (6) 5:10pm The Noise of Cairo (52) 11:10am Kids on Death Row (16) 6:05pm Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution (15) -

Strange Comrades: Non-Jihadist Foreign Fighters in Iraq & Syria

STRANGE COMRADES: NON-JIHADIST FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ & SYRIA Beleidsrapport Aantal woorden: 24.971 Simon De Craemer Stamnummer: 01004682 Promotor: Prof. dr. Marlies Casier Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de richting Politieke Wetenschappen afstudeerrichting Internationale Politiek Academiejaar: 2016 – 2017 Table of Contents 1. List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Non-jihadist foreign fighters: a theoretical basis ...................................................................................... 8 4. Historical timeline ................................................................................................................................................. 13 5. Case study ................................................................................................................................................................. 21 5.1 Data collection: building a foreign fighter database .............................................................................. 21 5.2 Data analysis and results ................................................................................................................................. 24 5.3 Profiles and groups of foreign fighters ..................................................................................................... -

Prison Escapes 5

PRISON ESCAPES 5 CONTENTS Redoine Faid (2013) George Blake (1966) Julien Chautard (2009) Prison Transit Van Escapes Pentonville Colditz Bizarre Escape attempts Many Others – Summaries for Discussion Redoine Faid escapes: It wasn't the first time that Faid, an armed robber being held in the death of a police officer, had gone on the lam. Here are a few other notorious prison escapes. • A special police officer stands guard in front the jail of Sequedin near Lille, northern France, April 14. Redoine Faid, an inmate, used explosives and took hostages to escape out of jail on Saturday morning, local media reported. PARIS Redoine Faid's escape from a French prison landed him on Interpol's most wanted list Monday, two days after he took four guards hostage and used explosives hidden inside tissue packets to blast his way out of a prison in Lille. Faid freed his hostages along his getaway route. It wasn't the first time that Faid, an armed robber being held in the death of a police officer, had gone on the lam. He was arrested in 1998 after three years on the run in Switzerland and Israel, according to the French media. Faid was freed after serving 10 years of his 31-year sentence, then swore he had turned his life around, writing a confessional book about his life of crime and going on an extensive media tour. "When I was on the run, I lived all the time with death, with fear of the police, fear of getting shot," he told Europe 1 radio at the time. -

An American Freedom Fighter in the Libyan Civil War: Part 1 | SOFREP 9/19/12 12:05 PM

An American Freedom Fighter in the Libyan Civil War: Part 1 | SOFREP 9/19/12 12:05 PM The TOC Comms Check SOFREP Explained The Loadout Room Team Room USASOC NSWC MARSOC AFSOC Coalition SOF PX Like 32 Tweet 12 3 StumbleUpon 22 Home » Special Operations » An American Freedom Fighter in the Libyan Civil War: Part 1 Site Search... An American Freedom Fighter in the Libyan Civil War: Part 1 by Jack Murphy · March 1, 2012 · Posted In: Special Operations Popular Recent Comments The Art of Women at War May 24, 2012, 1059 Comments Chicks Go to Ranger School May 20, 2012, 677 Comments Arab Spring Turns Into Modern Day Tet Offensive As Americans, especially those in military and intelligence circles, we have an obsession with giving everything a name or September 14, 2012, 746 Comments acronym. Everyone gets a label and category. I asked Matthew VanDyke what he was doing in the middle of the Libyan Civil War. Was he a mercenary, a private security contractor, or a foreign volunteer? His answer was straight forward and The Difference Between DELTA to the point: he was a freedom fighter. and SEAL TEAM SIX While the Huffington Post and others mistakenly reported that he was a journalist, Matt will tell you that he was anything April 6, 2012, 667 Comments but. He was conducting a recon mission when he was captured by the Libyan military and imprisoned. Once freed, he joined back up with the rebels and manned the unweildly Soviet DShK machine gun on a jeep that looked like something CIA Para-Military Personnel straight out of Mad Max, trading fire and getting into skirmishes with Gaddafi’s forces on the front lines of the war.