View and Print the Complete Guide in a Pdf File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARS!! the Litchfield Fund Weekly Newsletter

ALL EARS!! The Litchfield Fund Weekly Newsletter “We just don’t hear it on the street, we have our ears spread across all the fields!!!!!” In the calendar of Charlemagne, September was known as the Harvest Month. For ancient Britons, it was Barley Month, the crop ready for harvest. It was in September that Columbus departed the Canary Islands, the last stop before crossing the Atlantic & landing in the West Indies. In September, the Pilgrims, seeking religious freedom, departed Britain for the New World. September is the beginning of meteorological autumn & as we have seen this year, the peak of hurricane season is in early September. September is back to school month, the kick-off of football season at all levels & the thrill of tight baseball pennant races! See You in September: This 1966 #3 Billboard hit for The Happenings was written by Sid Wayne & Sherman Edwards. They were part of a songwriting group that was located in the Brill Building in Tin Pan Alley. The group included no less than Hal David, Burt Bacharach, Bobby Darin, Neil Sedaka, Neil Diamond, Gerry Goffin & Carole King. Mr. Wayne wrote many of the songs that were featured in Elvis Presley’s movies, partnering with other songwriters like Mr. Edwards, Ben Weisman & Abner Silver. Mr. Edwards wrote some early songs for Mr. Presley, but as the legend has it, walked out of songwriting session because of the demands of Mr. Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker. Saying he was tired of Rock’n’Roll, Mr. Edwards did not know what he would do next! But on March 16, 1969 a play, with songs written by Mr. -

Encores! 2016 Season Release

Contact:: Helene Davis Public Relations [email protected] NEW YORK CITY CENTER 2016 ENCORES! SEASON Cabin in the Sky Music by Vernon Duke; Lyrics by John La Touche Book by Lynn Root ~ 1776 America’s Prize Winning Musical Music and Lyrics by Sherman Edwards Book by Peter Stone Based on a Concept by Sherman Edwards ~ Do I Hear a Waltz? Music by Richard Rodgers; Lyrics by StePhen Sondheim Book by Arthur Laurents Based on the play The Time of the Cuckoo by Arthur Laurents Season Begins February 10, 2016 New York, NY, May 11, 2015– The 2016 season of New York City Center’s Tony-honored Encores! series will open with Cabin in the Sky on February 10–14, 2016, followed by 1776 and Do I Hear a Waltz?. Jack Viertel is the artistic director of Encores!; Rob Berman is its music director. Cabin in the Sky tells the fable-like story of a battle between The Lord’s General and the Devil’s only son over the soul of a charming ne’er-do-well named “Little Joe” Jackson who, after a knife fight in a saloon, is given six months more on earth to prove his worth. With Cabin in the Sky, composer Vernon Duke, lyricist John La Touche, and librettist Lynn Root set out to celebrate African American achievement in music and dance, and created a wonderfully integrated score that blends hits like “Taking a Chance on Love” with authentic traditional gospel numbers and full-fledged modern dance pieces. The show opened on October 25, 1940 at the Martin Beck Theatre in a production staged and choreographed by George Balanchine and ran 156 performances. -

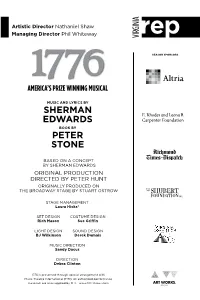

Sherman Edwards Peter Stone

Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw Managing Director Phil Whiteway 1776 SEASON SPONSORS AMERICA’S PRIZE WINNING MUSICAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY SHERMAN E. Rhodes and Leona B. EDWARDS Carpenter Foundation BOOK BY PETER STONE BASED ON A CONCEPT BY SHERMAN EDWARDS ORIGINAL PRODUCTION DIRECTED BY PETER HUNT ORIGINALLY PRODUCED ON THE BROADWAY STAGE BY STUART OSTROW STAGE MANAGEMENT Laura Hicks* SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN Rich Mason Sue Griffin LIGHT DESIGN SOUND DESIGN BJ Wilkinson Derek Dumais MUSIC DIRECTION Sandy Dacus DIRECTION Debra Clinton 1776 is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com CAST MUSICAL NUMBERS AND SCENES ACT I MEMBERS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS For God’s Sake, John, Sit Down ............................... Adams & The Congress Piddle, Twiddle ............................................................. Adams President Delaware Till Then .......................................................... Adams & Abigail John Hancock............ Michael Hawke Caesar Rodney ........... Neil Sonenklar The Lees of Old Virginia ......................................Lee, Franklin & Adams Thomas McKean ..... Andrew C. Boothby New Hampshire But, Mr. Adams — .................. Adams, Franklin, Jefferson, Sherman & Livingston George Read ................ John Winn Dr. Josiah Bartlett ......Joseph Bromfield Yours, Yours, Yours ................................................ Adams & Abigail Maryland He Plays the Violin ........................................Martha, -

Tennessee Repertory Theatre's by Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards

2005-2006 Season for Young People Teacher Guidebook Tennessee Repertory Theatre’s by Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards 2005- Thank You Tennessee Performing Arts Center gratefully acknowledges the generous support of corporations, foundations, government agencies, and other groups and individuals who have contributed to TPAC Education in 2005-2006. American Express Philanthropic Program The Hermitage Hotel Anderson Merchandisers Ingram Charitable Fund Aspect Community Commitment Fund Jack Daniel Distillery at Community Foundation Silicon Valley Juliette C. Dobbs 1985 Trust Baulch Family Foundation LifeWorks Foundation Bank of America Lyric Street BMI-Broadcast Music Inc. The Memorial Foundation Capitol Grille Gibson Guitar Corp. The Coca-Cola Bottling Company The HCA Foundation The Community Foundation of Middle Ingram Arts Support Fund Tennessee Lifeworks Foundation Creative Artists Agency Metro Action Commission Crosslin Vaden & Associates Martha & Bronson Ingram Foundation Curb Records Nashville Gas Company HCA/TriStar Neal & Harwell, PLC General Motors Corporation Mary C. Ragland Foundation Adventure 3 Properties, G.P. Pinnacle Financial Partners American Airlines RCA Label Group BellSouth Richards Family Advised Fund Bridgestone Firestone Trust Fund Rogan Allen Builders Davis-Kidd Booksellers Inc. Southern Arts Federation DEX Imaging, Inc. Starstruck Entertainment Dollar General Corporation SunTrust Bank, Nashville The Frist Foundation Fidelity Investments Earl Swensson Associates, Inc. Charitable Gift Fund Target Stores Patricia C. & Thomas F. Frist Designated Fund The Tennessean Gaylord Entertainment Company Ticketmaster Corporation General Motors Corporation Trauger, Ney, and Tuke The Joel C. Gordon & Bernice W. Gordon United Way of Metropolitan Nashville Family Foundation Universal South Glover Group Vanderbilt University Hecht's Vanderbilt University and Medical Center This project is funded under an agreement with the Tennessee Arts Commission, and the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Founding Fathers on Screen: the Changing Relationship Between History and Film

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film Jennifer Lynn Garrott College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Garrott, Jennifer Lynn, "Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626696. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-42hs-e363 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Founding Fathers on Screen: The Changing Relationship between History and Film Jennifer Lynn Garrott Burke, Virginia Bachelor of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2010 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon.G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary August 2012 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lynn Garrott Approved by the Committee, August, 2012 Committee Chair Associate Professor Leisa Meyer, Lyon Gardir/br Tyler History Department, The College of W illiam ^ Mary __________ Associate Professor Andrew Figjfer, Lyon Gardiner Tyler History Department, The College of William & Mary Visiting Assistant Professor Sharon ZuberI jlish and Film Studies The College of William' lary ABSTRACT PAGE While historians have often addressed, and occasionally dismissed historical films, the relationship between history and film is ever changing. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

City Center Announces Casting for 1776

Contact: Joe Guttridge, Director, Communications [email protected] 212.763.1279 John Behlmann, Nikki Renée Daniels, André De Shields, Santino Fontana, Alexander Gemignani, John Larroquette, Christiane Noll, Bryce Pinkham, Jubilant Sykes, and more will star in the Encores! production of 1776, directed by Garry Hynes, Mar 30—Apr 3 February 29, 2016/New York, NY—Encores! Artistic Director Jack Viertel today announced casting for the Encores! production of 1776, the classic Tony Award-winning musical about how the founding fathers drafted the Declaration of Independence and gave birth to a new nation. 1776 will star Terence Archie, John Behlmann, Larry Bull, Nikki Renée Daniels, André De Shields, Macintyre Dixon, Santino Fontana, Alexander Gemignani, John Hickok, John Hillner, John Larroquette, Kevin Ligon, John-Michael Lyles, Laird Mackintosh, Michael McCormick, Michael Medeiros, Christiane Noll, Bryce Pinkham, Wayne Pretlow, Tom Alan Robbins, Robert Sella, Ric Stoneback, Jubilant Sykes, Vishal Vaidya, Nicholas Ward, and Jacob Keith Watson. A unique show that presents John Adams (Santino Fontana), Thomas Jefferson (John Behlmann), and Benjamin Franklin (John Larroquette) in all their fractious, fascinating complexity, 1776 features such beloved songs as “Sit Down, John,” “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men,” and “He Plays the Violin.” Written by Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone, 1776 opened on Broadway on March 16, 1969, and ran for 1217 performances. The Encores! production will be directed by Garry Hynes, and choreography by Chris Bailey -

February 2019 Newsletter

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS February 2019 QUICK READS Fine-Free February for Kids! Holiday Hours Monday, February 18, the Library will be open On February 1 we will wipe the slate clean from 1 to 5 p.m. in honor of President’s Day. on the cards of every kid age twelve and under. All late fees will be forgiven, and Registration Note any blocks on accounts that are the Wednesday, February 6: result of late fees will be removed. Registration begins for a new 5-session Exercise Over 50 class on Fridays from 9-10 a.m. Class We hope this will encourage kids to begins on Friday, February 22. Register in person take full advantage of all the Library or online at www.pwpl.org/events has to offer and help them get reacquainted with the Library. Tax Help Register for a private tax help session, courtesy of Please note that the fine forgiveness AARP. Sessions are Tuesdays, February 5 through applies only to late fees, not to items April 9, between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. You do not you’ve been billed for or blocks have to be an AARP member. To register, visit the on accounts due to missing or damaged Reference Desk or call 516-883-4400 ext. 1400. materials. After fines are removed on February 1, new fines will begin accruing as usual. We hope your kids – and you – enjoy using the Library with freedom from fines! Homebound Delivery If you or a loved one is unable to come to visit the Library, we’ll arrange for free delivery of books and other materials. -

Champions Fairleigh Dickinson

FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON MEN’S BASKETBALL 2016 NORTHEAST CONFERENCE CHAMPIONS FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON MEN’S BASKETBALL FDUKNIGHTS.COM FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON 2015-16 FDU MEN’S BASKETBALL TEAM THE CURRENT STUDENT-ATHLETES & COACHING STAFF @FDUKNIGHTS FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON MEN’S BASKETBALL 2015-16 FDU MEN’S BASKETBALL ROSTER # NAME CL. POS. HT. WT. HOMETOWN / HIGHSCHOOL / LAST SCHOOL 1 Stephan Jiggetts R-So. G 6-1 205 Forestville, Md. / Bishop McNamara 2 Darian Anderson So. G 6-1 170 Washington, D.C. / St. John's College 3 DaRon Curry Fr. G 6-0 170 Deptford, N.J. / Phelps School 5 Earl Potts Jr. So. G/F 6-6 200 Severn, Md. / Archbishop Spalding 13 Tyrone O'Garro R-Jr. F 6-6 210 Newark, N.J. / Saint Peter's Prep 15 Marques Townes So. G 6-4 210 Edison, N.J. / St. Joseph (Metuchen) 20 Dondre Rhoden Fr. F 6-6 230 Ridgefield Park, N.J. / Ridgefield Park / Putnam Science 21 Myles Mann R-Jr. F 6-6 250 Atlanta, Ga. / Westlake 22 Darnell Edge Fr. G 6-1 175 Saugerties, N.Y. / Saugerties 23 Ghassan Nehme Fr. G 6-3 175 Colorado Springs, Colo. / Cheyenne Mountain 24 Mike Schroback So. G 5-10 175 Hasbrouck Heights, N.J. / Hasbrouck Heights 34 Mike Holloway Fr. F 6-7 245 Pittsgrove, N.J. / Arthur P. Schalick 35 Malik Miller Fr. C 6-9 215 Troy, N.Y. / Catholic Central Head Coach: Greg Herenda (Third Season, Merrimack ’83) Associate Head Coach: Bruce Hamburger Assistant Coaches: Dwayne Lee, Winston Smith Director of Basketball Operations: Pete Lappas DaRon Curry: duh-ron Stephan Jiggetts: Stuh-FON Jigg-etts Mike Schroback: SCHROW-back Marques Townes: Marcus Ghassan Nehme: GUH – saun Nahm-E Greg Herenda: Her-EN-duh FDUKNIGHTS.COM FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON • Stephan Jiggetts • So. -

Program for '1776' at Auditorium Theatre; April 26

AUDITORIUM THEATRE ROCHESTER APRIL 26, 1971 TO THEATRE CLUB MAY 1, 1971 SENECA DYERS INC. Specialists In SUEDE and LEATHER CLEANING • REFINISHI NG P.S. Gloves too! SINCE 1940 RETAIL DYERS OF WEARING APPAREL • HOUSEHOLD ITEMS CASH & CARRY OUR PLANT ONLY Open 7 AM-S PM • Sot 8 AM-1 PM 1227 MAPLE ST . (COR . MT . READ BLVD) 1328-17361 ROCHESTER ; NEW YORK "The Career Girl's Specialty Shop" 39 WEST MAIN STREET WEBSTER, NEW YORK 872-3322 Open daily from 9 A.M . to 5:45P.M. Thurs. & Fri . Nites to 8:45P.M. ORIGINAL BROADWAY CAST ON ~~~ COLUMBIA RECORDS t776 A New Musical ON SALE AT ALL MUSIC LOVERS STORES STUART OSTROW presents t7VO Music and Lyrics by SHERMAN EDWARDS Book by PETER STONE Based on a conception of SHERMAN EDWARDS Scenery and Lighting by JO MIELZINER costumes by PATRICIA ZIPPRODT Musical Direction by JONATHAN ANDERSON Orchestrations by EDDIE SAUTER Hair styles by ERNEST ADLER Associates Dance Director MAR TIN ALLEN Musical Numbers Staged by ONNA WHITE Directed by PETER HUNT PATRICK BEDFORD REX EVERHART GEORGE HEARN MICHAEL DAVIS- TRUMAN GAIGE- JACK MURDOCK- GEORGE BACKMAN BARBARA LANG- VIRGIL CURRY- GORDON DILWORTH KRISTEN BANFIELD- RICHARD MATHEWS- JOHN EAMES- DOUGLAS GORDON ED PREBLE- EDWIN COOPER- JAMES FERRIER ROBERT A. CALVERT- RAY LONERGAN- LARRY DEVON JAMES BOVAIRD- GRAHAM POLLOCK- LEE WINSTON CHRISTOPHER WYNKOOP- PATRICK COOK- MERVIN CROOK Original Cast Album on Columbia Records Intermission late comers will not be seated for I 5 minute 8 CIRCLE STREET • 473-3120 p c A R c A K T I I N N G GEORGE M. -

Senior Recital Program Notes

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Directed and Choreographed by Rachel Gorman & Ellen Wise Music Directed by Andrew James Craig Produced by Dr. Stephen Sachs As a courtesy, please turn off all cell phones and pagers. All recording and photography is prohibited. WHAT I SAY GOES: A MUSICAL REVUE OF MOTHERHOOD Montage from A Chorus Line Morgan Robertson-Soloist Ensemble Mama Who Bore Me from Spring Awakening Alyssa Aycock, Brooke Edwards, Rachel Gorman, Lashunda Thomas, Ellen Wise If Momma was Married from Gypsy Morgan Robertson-June; Jessica Ziegelbauer-Louise Stay with Me from Into the Woods Alyssa Aycock-Witch Superboy and the Invisible Girl from Next to Normal Temperance Jones-Daughter; Lashunda Thomas-Mother Hear My Song from Songs for a New World Joy Kenyon-Mother; Anna Rebmann-Mother Mama Says from Footloose Ensemble ~15 MINUTE INTERMISSION~ Mama, I’m a Big Girl Now from Hairspray Ensemble Mama, Look Sharp from 1776 Thaddeus Morris-Soldier; Ellen Wise-Mother Enough from In the Heights Alyssa Aycock-Daughter; Chadwick Harmon-Father; Temperance Jones-Mother Your Daddy’s Son from Ragtime Rachel Gorman-Sarah The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Brooke Edwards-Fredrika The I Love You Song from The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee Andrew James Craig-Father; Rachel Gorman-Mother; Ellen Wise-Daughter Mamma Mia from Mamma Mia! Ensemble PROGRAM NOTES Montage from A Chorus Line Various characters from the show express their experiences with motherhood. Written by Marvin Hamlisch and Edward Kleban Mama Who Bore Me from Spring Awakening The adolescent girls of Spring Awakening lament the lack of knowledge their mothers passed onto them, which left them ignorant about coming of age matters. -

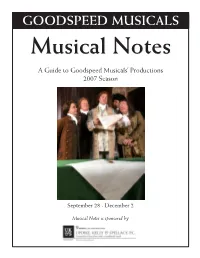

MUSICAL NOTES with Page Numbers Added

GOODSPEED MUSICALS A Guide to Goodspeed Musicals’ Productions 2007 Season September 28 - December 2 Musical Notes is sponsored by Music and Lyrics by SHERMAN EDWARDS Book by PETER STONE Based on a concept by SHERMAN EDWARDS Directed by ROB RUGGIERO Choreographed by RALPH D. PERKINS Music Direction by MICHAEL O’FLAHERTY Scenery Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by MICHAEL SCHWEIKARDT ALEJO VIETTI JOHN LASITER Orchestrations by Assistant Music Director DAN DeLANGE WILLIAM J. THOMAS Production Manager Production Stage Manager Casting by R. GLEN GRUSMARK BRADLEY G. SPACHMAN STUART HOWARD, AMY SCHECHTER, and PAUL HARDT, C.S.A. Associate Producer Line Producer BOB ALWINE DONNA LYNN COOPER HILTON Produced for Goodspeed Musicals by MICHAEL P. PRICE CAST OF CHARACTERS Members of the Continental Congress President John Hancock……………………………………....Alan Rust New Hampshire Dr. Josiah Bartlett…………………………………..Jack F. Agnew Massachusetts John Adams…………………………………………Peter A. Carey Rhode Island Stephen Hopkins…………………………………...John Newton Connecticut Roger Sherman……………………………………..Greg Roderick New York Robert Livingston…………………………………..Paul Jackel Lewis Morris………………………………………..Michael A. Pizzi New Jersey Rev. Jonathan Witherspoon………………………..Jerry Christakos Pennsylvania John Dickinson……………………………………..Jay Goede Ben Franklin………………………………………...Ronn Carroll James Wilson……………………………………….Marc Kessler Delaware Col. Thomas McKean……………………………...Kenneth Cavett George Read………………………………………..Dean Bellais Caesar Rodney……………………………………..Trip Plymale Maryland Samuel Chase……………………………………….Paul