Balkan Futures Three Scenarios for 2025

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

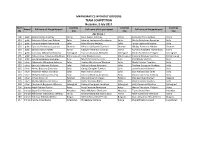

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS TEAM COMPETITION Nessebar, 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS TEAM COMPETITION Nessebar, 2 July 2017 Team Country/ Country/ Country/ Award Full name of the participant Full name of the participant Full name of the participant № City City City Age Group 1 108 gold Antoni Emilov Dimitrov Varna Boris Evgeni Dimitrov Varna Svetoslav Dariel Arabov Varna 113 gold Dobromir Miroslavov Dobrev Sofia Lubomir LachezarovGrozdanov Sofia Martin Borislavov Kovachev Sofia 114 gold Emma Andreeva Ikonomova Sofia Mina Filipova Nedeva Sofia Tanya Hristova Nihrizova Sofia 130 gold Gabriela Yordanova Lazarova Shumen Miroslav Stiliyanov Ganchev Shumen Nikolay Plamenov Nikolov Shumen 133 gold Damyan Ivanov Nakev Varna Kaloyan Klimentov Todorov Varna Rumena Nikolaeva Veznenkova Varna 135 gold Stanislava Mihaylova Bakalova Svilengrad Tsvetan Atanasov Mihaylov Svilengrad Viktor Zlatomirov Georgiev Svilengrad 136 gold Aleksandrina Adrianova Deshkova Dimitrovgrad Jivko Nikolov Ivanov Dimitrovgrad Valentin Nikolaev Stanchev Dimitrovgrad 138 gold Dimitar Rosislavov Bocharov Ruse Nikola Urasimirov Canev Ruse Vasil Kirilov Startsev Ruse 103 silver Aleksandra Mihaylova Getsova Sofia Andrea Miroslavova Nikolova Sofia Mochil Hristov Tsvetkov Sofia 115 silver Gabriela Valerieva Vuchova Sofia Melisa Sashova Antonova Sofia Preslava Georgieva Voykova Sofia 116 silver Albena Boykova Dimitrova Sofia Georgi Georgiev Tzenkov Sofia Luben Ivanov Hubenov Sofia 123 silver Alexander Petkov Cholakov Sofia Mark Petrov Zhivkov Sofia Sava Aleksandrov Delev Sofia 124 silver Michaela Galinova Grozeva Sofia Viktoria Nikolova -

Domestic Train Reservation Fees

Domestic Train Reservation Fees Updated: 17/11/2016 Please note that the fees listed are applicable for rail travel agents. Prices may differ when trains are booked at the station. Not all trains are bookable online or via a rail travel agent, therefore, reservations may need to be booked locally at the station. Prices given are indicative only and are subject to change, please double-check prices at the time of booking. Reservation Fees Country Train Type Reservation Type Additional Information 1st Class 2nd Class Austria ÖBB Railjet Trains Optional € 3,60 € 3,60 Bosnia-Herzegovina Regional Trains Mandatory € 1,50 € 1,50 ICN Zagreb - Split Mandatory € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of Croatia is the Croatian kuna (HRK). Croatia IC Zagreb - Rijeka/Osijek/Cakovec Optional € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of Croatia is the Croatian kuna (HRK). IC/EC (domestic journeys) Recommended € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of the Czech Republic is the Czech koruna (CZK). Czech Republic The currency of the Czech Republic is the Czech koruna (CZK). Reservations can be made SC SuperCity Mandatory approx. € 8 approx. € 8 at https://www.cd.cz/eshop, select “supplementary services, reservation”. Denmark InterCity/InterCity Lyn Recommended € 3,00 € 3,00 The currency of Denmark is the Danish krone (DKK). InterCity Recommended € 27,00 € 21,00 Prices depend on distance. Finland Pendolino Recommended € 11,00 € 9,00 Prices depend on distance. InterCités Mandatory € 9,00 - € 18,00 € 9,00 - € 18,00 Reservation types depend on train. InterCités Recommended € 3,60 € 3,60 Reservation types depend on train. France InterCités de Nuit Mandatory € 9,00 - € 25,00 € 9,00 - € 25,01 Prices can be seasonal and vary according to the type of accommodation. -

Haradinaj Et Al. Indictment

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA CASE NO: IT-04-84-I THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST RAMUSH HARADINAJ IDRIZ BALAJ LAHI BRAHIMAJ INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, charges: Ramush Haradinaj Idriz Balaj Lahi Brahimaj with CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OR CUSTOMS OF WAR, as set forth below: THE ACCUSED 1. Ramush Haradinaj, also known as "Smajl", was born on 3 July 1968 in Glodjane/ Gllogjan* in the municipality of Decani/Deçan in the province of Kosovo. 2. At all times relevant to this indictment, Ramush Haradinaj was a commander in the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës (UÇK), otherwise known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). In this position, Ramush Haradinaj had overall command of the KLA forces in one of the KLA operational zones, called Dukagjin, in the western part of Kosovo bordering upon Albania and Montenegro. He was one of the most senior KLA leaders in Kosovo. 3. The Dukagjin Operational Zone encompassed the municipalities of Pec/Pejë, Decani/Deçan, Dakovica/Gjakovë, and part of the municipalities of Istok/Istog and Klina/Klinë. As such, the villages of Glodjane/Gllogjan, Dasinovac/Dashinoc, Dolac/Dollc, Ratis/Ratishë, Dubrava/Dubravë, Grabanica/Grabanicë, Locane/Lloçan, Babaloc/Baballoq, Rznic/Irzniq, Pozar/Pozhare, Zabelj/Zhabel, Zahac/Zahaq, Zdrelo/Zhdrellë, Gramocelj/Gramaqel, Dujak/ Dujakë, Piskote/Piskotë, Pljancor/ Plançar, Nepolje/Nepolë, Kosuric/Kosuriq, Lodja/Loxhë, Barane/Baran, the Lake Radonjic/Radoniq area and Jablanica/Jabllanicë were under his command and control. -

Kosovo After Haradinaj

KOSOVO AFTER HARADINAJ Europe Report N°163 – 26 May 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE RISK AND DEFLECTION OF REBELLION................................................... 2 A. MANAGEMENT OF THE HARADINAJ INDICTMENT ..................................................................2 B. SHADOW WARRIORS TEST THE WATER.................................................................................4 C. THE "WILD WEST" ON THE BRINK ........................................................................................6 D. DUKAGJINI TURNS IN ON ITSELF ...........................................................................................9 III. KOSOVO'S NEW POLITICAL CONFIGURATION.............................................. 12 A. THE SHAPE OF KOSOVO ALBANIAN POLITICS .....................................................................12 B. THE OCTOBER 2004 ELECTIONS .........................................................................................13 C. THE NETWORK CONSOLIDATES CONTROL ..........................................................................14 D. THE ECLIPSE OF THE PARTY OF WAR? ................................................................................16 E. TRANSCENDING OR DEEPENING WARTIME DIVISIONS?.......................................................20 IV. KOSOVO'S POLITICAL SYSTEM AND FINAL STATUS.................................. -

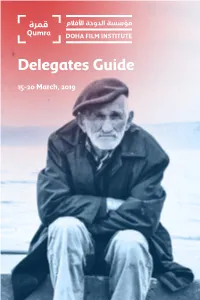

Delegates Guide

Delegates Guide 15–20 March, 2019 Cultural Partners Supported by Friends of Qumra Media Partners Cover: ‘Six Months and One Day’, directed by Yassine Ouahrani 1 QUMRA DELEGATES GUIDE Qumra Programming Team 5 Qumra Masters 7 Master Class Moderators 13 Qumra Project Delegates 15 Industry Delegates 63 QUMRA PROGRAMMING TEAM Fatma Al Remaihi CEO, Doha Film Institute Director, Qumra Aya Al-Blouchi Quay Chu Anthea Devotta Mayar Hamdan Qumra Master Classes Development Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Shorts Coordinator Senior Coordinator Executive Coordinator Development Assistant Youth Programmes Senior Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Senior Coordinator Elia Suleiman Artistic Advisor, Doha Film Institute Yassmine Hammoudi Karem Kamel Maryam Essa Al Khulaifi Meriem Mesraoua Qumra Industry Qumra Talks Senior Qumra Pass Senior Grants Senior Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Film Programming Senior QFF Programme Manager Hanaa Issa Coordinator Animation Producer Director of Strategy and Development Deputy Director, Qumra Vanessa Paradis Majid Al-Remaihi Nina Rodriguez Alanoud Al Saiari Grants Coordinator Film Programming Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Pass Coordinator Assistant Coordinator Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Wesam Said Rawda Al-Thani Jana Wehbe Ania Wojtowicz Grants Coordinator Film Programming Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Shorts Coordinator Assistant Coordinator Film Workshops & Labs Senior Coordinator Khalil Benkirane Ali Khechen Jovan Marjanović Head of Grants Qumra Industry Industry Advisor Manager Film Training Senior Manager 4 5 Qumra Masters Eugenio Caballero Kiyoshi Kurosawa In 2015 and 2016 he worked on the film ‘A at Cannes in 2003, ‘Doppelganger’ (2002), Monster Calls’, directed by J.A. Bayona, ‘Loft’ (2005), and ‘Retribution’ (2006), which earning him a Goya on his third nomination screened at that year’s Venice Film Festival. -

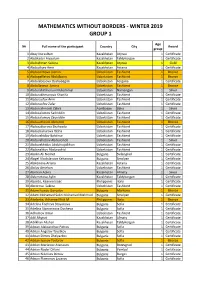

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2019 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2019 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abay Nursultan Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Certificate 2 Abdikadyr Aiyaulum Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 1 Certificate 3 Abdrahman Sabina Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Gold 4 Abdualiyev Amir Kazakhstan Astana 1 Certificate 5 Abduazimova Jasmin Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdugaffarov Abdulboriy Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 7 Abdulabosova Oyshabegim Uzbekistan Fergana 1 Certificate 8 Abdullayeva Amina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 9 Abdurahimhonov Mukammal Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 10 Abdurakhmanova Khanifa Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abduraufov Amir Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 12 Abduraufov Zafar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 1 Silver 14 Abdusalomov Sadriddin Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Abdusalomov Zayniddin Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 16 Abdusattarob Abdulloh Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 17 Abdusattorova Shahzoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 18 Abdushukurova Oisha Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 19 Abduvahidov Bahtinur Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 20 Abduvahobov Abduvohob Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 21 Abduvakhidov Abdulvojidkhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 22 Abduxalikov Abdurashid Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 23 Abidin Ali Nedret Bulgaria Svilengrad 1 Certificate 24 Abigel Vladislavova Kehayova Bulgaria Smolyan 1 Certificate 25 Abikenova Ariana Kazakhstan Astana 1 Certificate 26 Abilov Amirhan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 27 Abirhan Adina Kazakhstan -

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Negative trends associated with the media sphere in previous years persist, such as the media’s low level of professionalism, poor protection and conditions for journalists, a weak and oversaturated media market, an unsustainable public media service, a fragmented media scene, and political influence. BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA 16 EUROPE & EURASIA MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2014 introduction OVERALL SCORE: 2.04 BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) did not show signs of political or economic stabilization in 2013. The governing political parties avoided focusing on substantive reforms and implementing international standards. In April, Ba new political party launched—the Democratic Front, led by Željko Komšić, the Croat member of the B&H tripartite presidency. In the same month, the president of the Federation of B&H, Živko Budimir, was arrested on the accusation of taking bribes to approve amnesties but was released in May due to lack of evidence. In June 2013, public protests in front of Sarajevo’s parliament building and in other cities in B&H highlighted the lack of regulation of citizen IDs for newborns. The citizen initiative across B&H, although holding a promise of revolutionary change, ended as an unsuccessful bid to change politicians’ corruption, inequality, and incompetence. Finally, at the beginning of November, the B&H House of Peoples, in an emergency session and without debate, adopted the proposed amendments and changes to the law on ID numbers. The fact that the protests were organized through online platforms and social media illustrated new media’s growing influence in socially mobilizing the country. However, Serb and Croat parliamentarians framed the protests as an ethnically driven threat to their security and refused to attend parliamentary sessions for several weeks. -

[email protected], [email protected] Www

PERSONAL INFORMATION Name MARKO STOJANOVIĆ Address Telephone Mobil Fax E-mail [email protected], [email protected] Web www.worldmime.org and www.curling.rs Nationality Serbian Date of birth 2ND of January 1971. WORK EXPERIENCE • Dates (from – to) From 2013 to date • Name and address of employer BELGRADE YOUTH CENTRE “DOM OMLADINE BEOGRADA”, Makedonska 22, 11000 Belgrade, Telephone: + 381 (0) 11 322 01 27, www.domomladine.org; [email protected] • Type of business or sector Belgrade Youth Centre is a cultural institution of the City of Belgrade • Occupation or position held Acting GENERAL MANAGER and Director of the Belgrade Jazz Festival • Main activities and responsibilities Organising work process and managing employees as well as artists and finances. Development and improvement of programs, work processes and financial situation. Developing relationships with Belgrade, Serbian and international youth as primary audience, but with city and state governments, core diplomatique, ngo's, youth, educational and artistic institutions, formal and informal groups and individuals. Produceing the Belgrade Jazz Festival since 1971. • Dates (from – to) From 2013 and 2014 • Name and address of employer SINGIDUNUM UNIVERSITY, Danijelova 32, 11000 Belgrade, Telephone: + 381 (0) 11 3093 220, www.singidunum.ac.rs ; [email protected] • Type of business or sector Management and Communication • Occupation or position held LECTURER AND PR CONSULTANT • Main activities and responsibilities Teaching Communication Skills and Public -

Chapitre 0.Indd

Crosswalking EUR-Lex Crosswalking OA-78-07-319-EN-C OA-78-07-319-EN-C Michael Düro Michael Düro Crosswalking EUR-Lex: Crosswalking EUR-Lex: a proposal for a metadata mapping a proposal for a metadata mapping to improve access to EU documents : to improve access to EU documents a proposal for a metadata mapping to improve access to EU documents to access improve mapping to a metadata for a proposal The Oce for Ocial Publications of the European Michael Düro has a background The Oce for Ocial Publications of Communities oers direct free access to the most complete in information science, earned a Masters the European Communities collection of European Union law via the EUR-Lex online in European legal studies and works in is the publishing house of the institu- database. the EUR-Lex unit of the Oce for Ocial tions, agencies and other bodies of the Publications of the European The value of the system lies in the extensive sets of metadata European Union. Communities. which allow for ecient and detailed search options. He was awarded the The Publications Oce produces and Nevertheless, the European institutions have each set up Dr. Eduard-Martin-Preis for outstanding distributes the Ocial Journal of the their own document register including their own sets of research in 2008 by the University of European Union and manages the metadata, in order to improve access to their documents and Saarland, Germany, for this thesis. EUR-Lex website, which provides direct meet the increasing need for transparency. free access to European Union law. -

BALKANS-Eastern Europe

Page 16-BALKANS Name: __________________________ BALKANS-Eastern Europe WHAT ARE THE BALKANS??? World Book Online—Type in the word “BALKANS” in the search box, it is the first link that comes up. Read the first paragraph. The Balkans are ____________________________________________________________________________. “Balkan” is a word that means- _______________________________________________________. Why are the Balkans often called the “Powder Keg of Europe”:? Explain: ________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ On the right-side of the page is a Map-Balkan Peninsula Map---click on the map. When you have the map open, look and study it very carefully: How many countries are located in the Balkans (country names are in all bold-face): ______________ List the countries located in the Balkans today: _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ Go back to World Book Online search box: type in Yugoslavia---click on the 1st link that appears. Read the 1st paragraph. Yugoslavia was a _______________________________________________________. Click on the map on the right---Yugoslavia from 1946 to 2003. Look/study in carefully. Everything in orange AND yellow was a part of Yugoslavia from _____________ to __________________. Everything in light yellow was also a part of Yugoslavia from ____________ to ________________. So the big issue/question then is what happened to the country of Yugoslavia starting in 1991, through 2003 when the country of Yugoslavia ceases to exist. The video (and questions) on the back will help explain the HORRIFIC break-up of Yugoslavia and what really happened—and why it is still a VERY volatile region of the world even today. Page 16-BALKANS Name: __________________________ Terror in the Balkans: Breakup of Yugoslavia 1. -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

Rita Ora– I Will Never Let You Down

Rita Ora – I Will bitenewsingles Never Let You Down e have truly missed singing sensation Rita Ora! Now she’s back with a new single, ‘I Will Never Let You Down’ written by beau Calvin Harris, and a sexy and stylish hairdo. The new single is the first release from ORA RITA her forthcoming sophomore album and if her certified platinum first Walbum, Ora, is anything to go by, which clocked up an incredible three consecutive No.1 singles, her second offering should also set the charts ablaze. ‘I Will Never Let You Down’ is said to be the perfect union of two huge powerhouses making the ultimate feel good song. Rita said: “This is the perfect song to launch my new album because I wanted to be as personal and honest as possible. I’m in a very good place and I really wanted people to see how I felt and how I want other people to feel when they listen to it – happy! I love the fact this is such an uplifting love song.” To bring her creative vision to life for the new single, Rita enlisted the help of Italian-born photographer and Emmy-Award-nominated director Francesco Carrozzini, who has worked with global A-list stars such as Natalie Portman, Scarlett Johanssen, Naomi Campbell and Beyoncé. As well as shooting the artwork for the campaign, the director worked closely with the singer to create the stunning video for ‘I Will Never Let You Down’. Despite being absent from our airwaves for a time, Rita has been working hard on home turf in the UK and stateside on her album.