The Peak Oil Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coal and Oil: the Dark Monarchs of Global Energy – Understanding Supply and Extraction Patterns and Their Importance for Futur

nam et ipsa scientia potestas est List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Höök, M., Aleklett, K. (2008) A decline rate study of Norwe- gian oil production. Energy Policy, 36(11):4262–4271 II Höök, M., Söderbergh, B., Jakobsson, K., Aleklett, K. (2009) The evolution of giant oil field production behaviour. Natural Resources Research, 18(1):39–56 III Höök, M., Hirsch, R., Aleklett, K. (2009) Giant oil field decline rates and their influence on world oil production. Energy Pol- icy, 37(6):2262–2272 IV Jakobsson, K., Söderbergh, B., Höök, M., Aleklett, K. (2009) How reasonable are oil production scenarios from public agen- cies? Energy Policy, 37(11):4809–4818 V Höök M, Söderbergh, B., Aleklett, K. (2009) Future Danish oil and gas export. Energy, 34(11):1826–1834 VI Aleklett K., Höök, M., Jakobsson, K., Lardelli, M., Snowden, S., Söderbergh, B. (2010) The Peak of the Oil Age - analyzing the world oil production Reference Scenario in World Energy Outlook 2008. Energy Policy, 38(3):1398–1414 VII Höök M, Tang, X., Pang, X., Aleklett K. (2010) Development journey and outlook for the Chinese giant oilfields. Petroleum Development and Exploration, 37(2):237–249 VIII Höök, M., Aleklett, K. (2009) Historical trends in American coal production and a possible future outlook. International Journal of Coal Geology, 78(3):201–216 IX Höök, M., Aleklett, K. (2010) Trends in U.S. recoverable coal supply estimates and future production outlooks. Natural Re- sources Research, 19(3):189–208 X Höök, M., Zittel, W., Schindler, J., Aleklett, K. -

Working Paper

WORKING PAPER The Value of Oil Price Projectiom Nebojsa Nakinnovic Leo SchrattenhoLzer October 1935 IQ-85-68 lnternrtionrl Institute tor -lid System, Anrlyth NOT FOR QUOTATION WITHOUT THE PERMISSION OF THE AUTHORS The Value of Oil Price Projections Nebo jsa Nakicenovic Leo SchrattenhoLzer October 1935 TW-85-68 Working Papers are interim reports on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and have received only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Institute or of its National Member Organizations. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED SYSTEMS ANALYSIS 2361 Laxenburg, Austria -ABSTRACT AND SUBXAXY The central theme of this paper is the development of the international price of crude oil. A short overview of oil price his6ry is followed by a discussion of the factors that were responsible for previous, sometimes erratic, changes. We con- clude that these factors are likely to maintain their influence in the future, thus giving the forecasts of oil prices a high uncertainty. This uncertainty is reflected in several reports containing oil price proje[ctions. We argue, therefore, that a question soieiy about future oil prices must remain unanswered. Tnis does not render the efforts to examine the future futile; it simpiy means that the question shouid be rephrased. We offer one possible problem formulation that explicitly accounts for the high uncertainty. This formulation requires that specific policy probiems and options for solving them be specified before oil prices are projected - a condition that does not always hold or, at least, that does not seem to be regarded as important enougn to be described in many reports on oil price studies. -

U.S. Energy in the 21St Century: a Primer

U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer March 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46723 SUMMARY R46723 U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer March 16, 2021 Since the start of the 21st century, the U.S. energy system has changed tremendously. Technological advances in energy production have driven changes in energy consumption, and Melissa N. Diaz, the United States has moved from being a net importer of most forms of energy to a declining Coordinator importer—and a net exporter in 2019. The United States remains the second largest producer and Analyst in Energy Policy consumer of energy in the world, behind China. Overall energy consumption in the United States has held relatively steady since 2000, while the mix of energy sources has changed. Between 2000 and 2019, consumption of natural gas and renewable energy increased, while oil and nuclear power were relatively flat and coal decreased. In the same period, production of oil, natural gas, and renewables increased, while nuclear power was relatively flat and coal decreased. Overall energy production increased by 42% over the same period. Increases in the production of oil and natural gas are due in part to technological improvements in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that have facilitated access to resources in unconventional formations (e.g., shale). U.S. oil production (including natural gas liquids and crude oil) and natural gas production hit record highs in 2019. The United States is the largest producer of natural gas, a net exporter, and the largest consumer. Oil, natural gas, and other liquid fuels depend on a network of over three million miles of pipeline infrastructure. -

Oil Shale and Tar Sands

Fundamentals of Materials for Energy and Environmental Sustainability Editors David S. Ginley and David Cahen Oil shale and tar sands James W. Bunger 11 JWBA, Inc., Energy Technology and Engineering, Salt Lake City, UT, USA 11.1 Focus 11.2 Synopsis Tar sands and oil shale are “uncon- Oil shale and tar sands occur in dozens of countries around the world. With in-place ventional” oil resources. Unconven- resources totaling at least 4 trillion barrels (bbl), they exceed the world's remaining tional oil resources are characterized petroleum reserves, which are probably less than 2 trillion bbl. As petroleum becomes by their solid, or near-solid, state harder to produce, oil shale and tar sands are finding economic and thermodynamic under reservoir conditions, which parity with petroleum. Thermodynamic parity, e.g., similarity in the energy cost requires new, and sometimes of producing energy, is a key indicator of economic competitiveness. unproven, technology for their Oil is being produced on a large commercial scale by Canada from tar sands, recovery. For tar sands the hydrocar- and to a lesser extent by Venezuela. The USA now imports well over 2 million barrels bon is a highly viscous bitumen; for of oil per day from Canada, the majority of which is produced from tar sands. oil shale, it is a solid hydrocarbon Production of oil from oil shale is occurring in Estonia, China, and Brazil albeit on called “kerogen.” Unconventional smaller scales. Importantly, the USA is the largest holder of oil-shale resources. oil resources are found in greater For that reason alone, and because of the growing need for imports in the USA, quantities than conventional petrol- oil shale will receive greater development attention as petroleum supplies dwindle. -

Husky Energy and BP Announce Integrated Oil Sands Joint Development

December 5, 2007 For immediate release Husky Energy and BP Announce Integrated Oil Sands Joint Development CALGARY, Alberta – Husky Energy Inc is pleased to announce that an agreement has been reached with BP to create an integrated, North American oil sands business consisting of pre-eminent upstream and downstream assets. The development will be comprised of two joint 50/50 partnerships, a Canadian oil sands partnership to be operated by Husky and a U.S. refining LLC to be operated by BP. Husky and BP will each contribute assets of equal value to the business. Husky will contribute its Sunrise asset located in the Athabasca oil sands in northeast Alberta, Canada and BP will contribute its Toledo refinery located in Ohio, USA. The transaction, which is subject to the execution of final definitive agreements and regulatory approval, is expected to close in the first quarter of 2008 and with effective date January 1, 2008. "This transaction completes Husky’s Sunrise Oil Sands total integration with respect to upstream and downstream solutions," said Mr. John C.S. Lau, President & Chief Executive Officer of Husky Energy Inc. “Husky is extremely pleased to be partnering with BP, a world class global E & P and Refining company. The joint venture will provide better monitoring of project execution, costs and completion timing for this mega project development.” “Toledo and Sunrise are excellent assets. BP’s move into oil sands with Husky is an opportunity to build a strategic, material position and the huge potential of Sunrise is the ideal entry point for BP into Canadian oil sands.” said Tony Hayward, BP’s group chief executive. -

Peak Oil, Peak Energy Mother Nature Bats Last

Peak Oil, Peak Energy Mother Nature Bats Last Martin Sereno 1 Feb 2011 (orig. talk: Nov 2004) Oil is the Lifeblood of Industrial Civilization • 80 million barrels/day, 1000 barrels/sec, 1 cubic mile/year • highly energy-dense • easy to transport, store • moves goods and people • allows us to fly (there will never be a battery-operated jet plane) • digs huge holes and puts up huge buildings • ballooned our food supply (fertilize, cultivate, irrigate, transport) • our 'stuff' is made from it (iPods to the roads themselves) • we're not "addicted to oil" -- that's like saying a person has an "addiction to blood" Where Oil Comes From • raw organic material for oil (e.g., from plankton) is present in low concentrations in ‘all’ sedimentary rocks, but esp. from two warm periods 90 million and 140 million years ago • temperature rises with depth (radioactivity, Kelvin’s mistake) • oil is generated in rocks heated to 60-120 deg Celsius • rocks at this temp. occur at different depths in different places (N.B.: water depth doesn't count) • oil is ‘cracked’ to natural gas at higher temps (deeper) • abiotic oil from “crystalline basement” is negligible, if it exists • exhausted oil fields do not refill Recoverable Oil • oil must collect in a “trap” to be practically recoverable • a trap is a permeable layer capped by an impermeable one • obvious traps: anticlines, domes (“oil in those hills”) • less obvious traps found by seismic imaging: turned up edges of salt domes, near buried meteorite crater (Mexico) • harder-to-get-at traps: shallow continental shelf (GOM) • even-harder-to-get-at traps: edge continental slope (Macondo, resevoir pressure: 12,000 pounds [6 tons] per sq inch) • essentially no oil in basaltic ocean floor or granitic basement (Used to be!) Second Largest Oilfield Cantarell used to supply 2% of world oil (water) Guzman, A.E. -

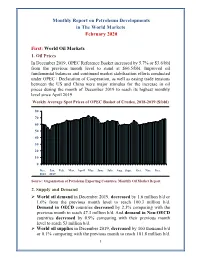

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in the World Markets February 2020

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in The World Markets February 2020 First: World Oil Markets 1. Oil Prices In December 2019, OPEC Reference Basket increased by 5.7% or $3.6/bbl from the previous month level to stand at $66.5/bbl. Improved oil fundamental balances and continued market stabilization efforts conducted under OPEC+ Declaration of Cooperation, as well as easing trade tensions between the US and China were major stimulus for the increase in oil prices during the month of December 2019 to reach its highest monthly level since April 2019. Weekly Average Spot Prices of OPEC Basket of Crudes, 2018-2019 ($/bbl) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. 2018 2019 Source: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Monthly Oil Market Report. 2. Supply and Demand World oil demand in December 2019, decreased by 1.6 million b/d or 1.6% from the previous month level to reach 100.3 million b/d. Demand in OECD countries decreased by 2.3% comparing with the previous month to reach 47.3 million b/d. And demand in Non-OECD countries decreased by 0.9% comparing with their previous month level to reach 53 million b/d. World oil supplies in December 2019, decreased by 100 thousand b/d or 0.1% comparing with the previous month to reach 101.8 million b/d. 1 Non-OPEC supplies remained stable at the same previous month level of 67.2 million b/d. Whereas preliminary estimates show that OPEC crude oil and NGLs/condensates total supplies decreased by 0.6% comparing with the previous month to reach 34.5 million b/d. -

Price Forecast June 30, 2015 Contents

Resource Evaluation & Advisory Price forecast June 30, 2015 Contents Canadian price forecast 1 International price forecast 5 Global outlook 6 Western Canada royalty comparison 8 Pricing philosophy 11 Glossary 12 Canadian domestic price forecast Forecast commentary Andrew Botterill Senior Manager, Resource Evaluation & Advisory “Everything is in a state of fl ux, including status quo” - Robert Byrne As industry adjusts to the “new normal” we have analyzed This narrowing has been most notable on the heavy oil in our last two forecasts, activities in the energy sector side, where diff erentials have decreased more than 30 per are beginning to demonstrate a cautious, but optimistic cent compared with where they were in summer 2014. view of the future. While not anticipating $100 oil in the With greater than 60 per cent of Canadian production near term, these views show an expectation industry will being from oil sands (CAPP 2015 forecast report) the bring a more focused approach to North American oil narrowing of heavy diff erentials is welcome news to much development within the coming 12 to 18 months. of the sector. In recent weeks, the WTI to heavy diff erential has been narrower than we have seen recently as In recent weeks, Canadian-received oil prices have been production from some projects was shut-in due to wildfi res stronger relative to the beginning of the year, with daily in northern Alberta. The shut-in production has since been WTI settlements hovering around $60/bbl USD and brought back on-stream, which has slowed the narrowing Canadian Light settlements greater than $70/bbl CAD. -

1 OXREP the Future of Fossil Fuels – Is It the End? Dieter Helm1 12Th January 2016 Abstract Contrary to the Assumptio

OXREP The future of fossil fuels – is it the end? Dieter Helm1 12th January 2016 Abstract Contrary to the assumptions underlying much of current energy and climate policies, fossil fuels have fallen and may remain at the new “normal” levels. In the medium term, Iran and Iraq have considerable potential to increase their outputs, and the new shale technologies will gradually globalise. Longer term, new technologies in electricity generation, storage and smart demand side technologies, together with electric cars and the shift towards digitalisation and new electricity-based technologies in manufacturing, with increase demand for electricity, but not fossil fuels. These new and emerging technologies, rather than international agreements, and the promotion of current generation renewables, will probably bring fossil fuel dominance to a gradual close. To facilitate decarbonisation, energy policy should be directed at enhancing R&D and next generation renewables, instead of supporting existing ones. JEL classification: Q4, L9, O3. 1.Introduction 1 Comments on drafts by Ken Mayhew, Alex Teytelboym, and Christopher Adams are gratefully acknowledged and discussions with Cameron Hepburn, John Feddersen and Ben Irons have also very helped. All errors remain mine. 1 The demise of fossil fuels has been often predicted, but they have proved remarkably resilient. Stanley William Jevons in the nineteenth century worried that Britain was running out of coal, and would as a result have to return “to her former littleness”2. Yet nobody worries that the world is going to run out of coal a century and a half later. For oil, the end has been predicted in almost every decade since the modern oil industry was founded. -

The Price of Oil Risk

The Price of Oil Risk Steven D. Baker,∗ Bryan R. Routledge,y [February 10, 2017] Abstract We solve a Pareto risk-sharing problem for two agents with heterogeneous re- cursive utility over two goods: oil, and a general consumption good. Using the optimal consumption allocation, we derive a pricing kernel and the price of oil and related futures contracts. This gives us insight into the dynamics of prices and risk premia. We compute portfolios that implement the optimal consumption policies, and demonstrate that large and variable open interest is a property of optimal risk-sharing. A numerical example of our model shows that rising open interest and falling oil risk premium are an outcome of the dynamic properties of the optimal risk sharing solution. ∗ McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia; [email protected]. y Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University; [email protected]. 1 Introduction The spot price of crude oil, and commodities in general, experienced a dramatic price increase in the summer of 2008. For oil, the spot price peaked in early July 2008 at $145.31 per barrel (see Figure 1). In real-terms, this price spike exceeded both of the OPEC price shocks of 1970's and has lasted much longer than the price spike at the time of the Iraq invasion of Kuwait in the summer of 1990. The run-up to the July 2008 price of oil begins around 2004. Buyuksahin, Haigh, Harris, Overdahl, and Robe (2011) and Hamilton and Wu (2014) identify a structural change in the behavior of oil prices around 2004. -

A Comparative History of Oil and Gas Markets and Prices: Is 2020 Just an Extreme Cyclical Event Or an Acceleration of the Energy Transition?

April 2020 A Comparative History of Oil and Gas Markets and Prices: is 2020 just an extreme cyclical event or an acceleration of the energy transition? Introduction Natural gas markets have gone through an unprecedented transformation. Demand growth for this relatively clean, plentiful, versatile and now relatively cheap fuel has been increasing faster than for other fossil fuels.1 Historically a `poor relation’ of oil, gas is now taking centre stage. New markets, pricing mechanisms and benchmarks are being developed, and it is only natural to be curious about the direction these developments are taking. The oil industry has had a particularly rich and well recorded history, making it potentially useful for comparison. However, oil and gas are very different fuels and compete in different markets. Their paths of evolution will very much depend on what happens in the markets for energy sources with which they compete. Their history is rich with dominant companies, government intervention and cycles of boom and bust. A common denominator of virtually all energy industries is a tendency towards natural monopoly because they have characteristics that make such monopolies common. 2 Energy projects tend to require multibillion – often tens of billions of - investments with long gestation periods, with assets that can only be used for very specific purposes and usually, for very long-time periods. Natural monopolies are generally resolved either by new entrants breaking their integrated market structures or by government regulation. Historically, both have occurred in oil and gas markets.3 As we shall show, new entrants into the oil market in the 1960s led to increased supply at lower prices, and higher royalties, resulting in the collapse of control by the major oil companies. -

Secure Fuels from Domestic Resources ______Profiles of Companies Engaged in Domestic Oil Shale and Tar Sands Resource and Technology Development

5th Edition Secure Fuels from Domestic Resources ______________________________________________________________________________ Profiles of Companies Engaged in Domestic Oil Shale and Tar Sands Resource and Technology Development Prepared by INTEK, Inc. For the U.S. Department of Energy • Office of Petroleum Reserves Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves Fifth Edition: September 2011 Note to Readers Regarding the Revised Edition (September 2011) This report was originally prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy in June 2007. The report and its contents have since been revised and updated to reflect changes and progress that have occurred in the domestic oil shale and tar sands industries since the first release and to include profiles of additional companies engaged in oil shale and tar sands resource and technology development. Each of the companies profiled in the original report has been extended the opportunity to update its profile to reflect progress, current activities and future plans. Acknowledgements This report was prepared by INTEK, Inc. for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Petroleum Reserves, Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves (DOE/NPOSR) as a part of the AOC Petroleum Support Services, LLC (AOC- PSS) Contract Number DE-FE0000175 (Task 30). Mr. Khosrow Biglarbigi of INTEK, Inc. served as the Project Manager. AOC-PSS and INTEK, Inc. wish to acknowledge the efforts of representatives of the companies that provided information, drafted revised or reviewed company profiles, or addressed technical issues associated with their companies, technologies, and project efforts. Special recognition is also due to those who directly performed the work on this report. Mr. Peter M. Crawford, Director at INTEK, Inc., served as the principal author of the report.